Definition/Introduction

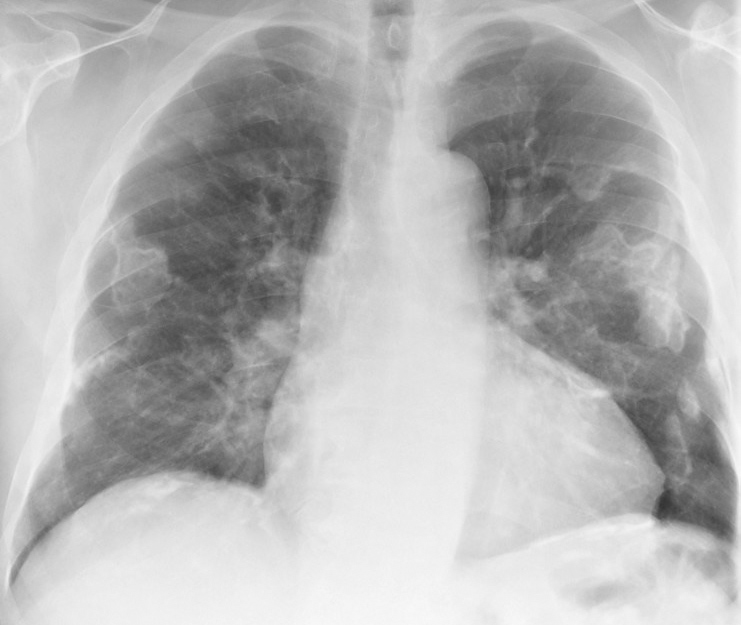

X-ray examinations are generally classified into 3 categories: radiography, fluoroscopy, and computed tomography. Radiography employs film or a solid-state image receptor to acquire static images for interpretation by a radiologist (see Image. X-ray, Anterior View, Lungs, Asbestos).[1] Fluoroscopy is classically employed with an x-ray tube under an examination table while providing images on a monitor or display, typically in real-time.[2] Computed tomography (CT) employs an x-ray source coupled with a detector array rotating around the patient with subsequent reconstruction of images into different planes.

Issues of Concern

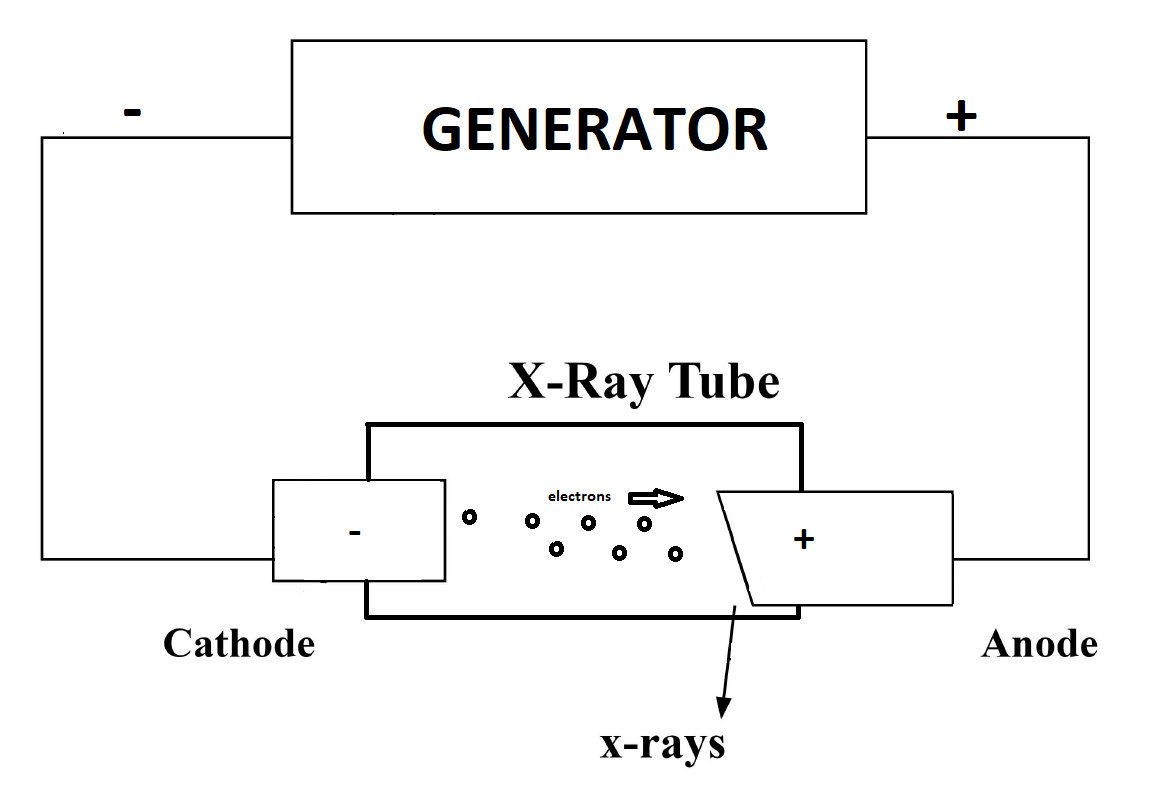

X-ray System Components - X-ray currents are measured in milliamperes(mA), while x-ray voltages are measured in kilovolt peak (kVp).[3] X-ray imaging systems generally comprise a few primary components: the operating console, the high-voltage generator, the x-ray tube, and the receiver (see Image. X-ray Generator). Operating consoles allow an operator to select a kVp, mA, and time. The console allows a technologist to establish an x-ray beam of adequate quantity (number of x-ray photons) and quality (effective energy of x-ray photons). Control of milliampere (mA), which constitutes the x-ray tube current traversing from the cathode to the anode, is monitored with an mA meter. The number of x-rays reaching an image receptor is also related to the time the tube is energized, initiated, and terminated by the radiographer.

Timing Circuits - The different timing circuits include synchronous timers, electronic timers, mAs timers, and automatic exposure control (AEC).[4] Electronic timers are the most accurate and allow time interval selection, while AEC terminates exposure based on detected radiation intensity.

Power for Production - Power is provided by the high-voltage generator, which allows for increasing an output voltage to a kVp needed for x-ray production. A technologist needs to be aware that variations in supply voltage in clinics and hospitals result in a large variation in the production of an x-ray beam, affecting image quality and patient exposure.[5]

Ceiling Support and the Vacuum Tube - The ceiling support system helps provide the primary support for an x-ray tube and serves as a protective apparatus. Among its many functions, the primary 1 is to avoid leakage and help in heat dissipation. The vacuum tube is composed of an anode and cathode within an enclosure. The cathode, which contains a tungsten filament, serves as the electron source, while a rotating anode, composed of a tungsten disc, serves as the electron target.[6] Tube failure has many causes, primarily excessive anode heating, anode cracking/pitting, and filament vaporization. Tube rating charts can help assess exposure levels and their relation to tube durability.

X-ray Production - The primary result of electron acceleration from the cathode to the anode includes heat production, bremsstrahlung x-rays, and characteristic x-ray production. Characteristic x-rays are produced as a process of ionization by inner electron-shell emission and subsequent filling of the orbital void. Bremsstrahlung x-rays are produced by electron deceleration secondary to atomic field effects, producing diagnostic range x-rays from this energy loss.[7] X-ray quantity is determined by mAs, kVp, distance, and filtration, while kVp and filtration determine x-ray quality. The x-ray beam from the tube contains photons of varying energy with a high proportion of low-energy photons, which have a negligible impact on image production as they cannot traverse the patient to reach the detector and thereby only contribute to patient dose and not image quality. Filters absorb these low-energy photons, thereby reducing the unnecessary dose to the patient. The process of filtering out the low-energy photons is termed beam hardening. This process decreases x-ray tube output but generates a more uniform beam with an overall increased average x-ray energy. The types of filtration include inherent filtration of the enclosure, compensation filters, and aluminum sheets, which serve as added filters.

X-ray Interactions - Interactions between x-rays and matter are characterized by coherent, Compton, and photoelectric effect interactions.[8] Compton scattering occurs when atoms are ionized by incident x-rays, with a change in x-ray direction and subsequent energy loss. The photoelectric effect occurs with incident x-ray absorption and subsequent photoelectron emission. Together, the photoelectric effect and Compton scattering are interactions of clinical importance in diagnostic x-ray imaging. Differential absorption by tissue affects the contrast of x-ray image and is secondary to the atomic number of the tissue in atoms, the x-ray energy, and tissue density.[9] Contrast agents such as iodine also affect differential absorption due to their high atomic numbers.

Image Quality - Several factors determine image quality but are best characterized by a high signal-to-noise ratio (low noise) and good spatial resolution. Additional factors include factors relating to film processing, factors relating to geometric characteristics (such as magnification), and factors relating to the patient. The technologist has an important role in maintaining good image quality. For example, preventing patient movement helps reduce motion blur.[3] X-rays can either pass through a patient or are scattered by Compton interaction, which results in noise. Also, high kVp worsens the signal-to-noise ratio, while the thickness of the tissue being penetrated also increases noise. Using higher kVp results in an x-ray beam of higher average energy requiring a shorter exposure time and mA (together referred to as tube current exposure time product value or mAs), increasing patient penetration but also resulting in increased scatter and decreased image contrast. The converse is also true. A lower kVp setting requires increased mAs, resulting in decreased patient penetration, decreased scatter, and increased contrast. Carefully balancing these factors is essential for managing the relationship between patient dose, image contrast, and quality. Reduction of scatter radiation can be achieved by using grids, which have the added benefit of improving contrast and play an important role in producing an adequate quality and interpretable radiographic image. Although kVp increases noise, it also reduces patient dose. Collimators are devices that restrict/narrow beams and control scatters, resulting in increased signal-to-noise and decreased patient dose. In addition to image contrast, spatial resolution is an important measure of image quality. A smaller field of view results in a higher spatial resolution of the image and a decreased overall dose to the patient.

Important Elements of Image Acquisition - Screen film X-ray images are produced when an image receptor cassette is exposed to an existing x-ray beam.[10] The image receptor cassette contains a radiographic film between 2 intensifying screens. The radiographic film is made up of a base covered by film emulsion. The film emulsion component contains silver bromide crystals, which are light-sensitive. Silver bromide crystals interact with light photons to form a radiographic image. The technologist plays an important role in manipulating kVp and mAs in image production. These factors influence the quantity and quality of x-rays, influencing contrast and image quality. The source-image distance (SID) is the distance from the tube to the receptor. Along with mAs and kVp, the SID influences factors such as contrast, distortion, magnification, and optical density. Functional technique charts (including fixed-kVp and high-kVp charts) are used to produce radiographs depending on the type of study (body part) and other factors, such as the x-ray machine itself. Anatomically Programmed Radiography plays a role in automatically selecting kVp and mAs depending on the technologist’s selection of an anatomic part. Screen film radiography has been nearly completely replaced by digital radiography in the United States.

Digital Radiography - The computed radiographic image receptor, an elementary form of a digital detector, is similar yet different from screen-film imaging in a few ways. One similarity is their mutual use of X-ray-sensitive plates. Computed radiography using storage phosphors uses trapped electrons in metastable states to produce an image instead of a scintillator used in screen-film radiography. Metastable electrons are released with a stimulating laser beam, with the emission of light on the return of these electrons to a ground state.[11] This light emission is used to establish an image. Computed radiography also comparatively has a reduced radiation dose and better contrast resolution when compared to screen radiography (although the resolution is worse in digital radiography). Flat Panel Detectors are classically associated with digital detectors. It is faster than film radiography and includes direct and indirect systems. Explained simply, indirect systems require a latent image to be released as a light, then converted to a charge and a digital image. In contrast, direct systems directly convert x-rays into charge (and subsequently an image) without this intermediate step. Indirect systems employ a cesium iodide scintillator, which constitutes most flat-panel detectors, while direct systems employ amorphous selenium.

Minimizing X-ray Exposure - The mantra of decreasing radiation exposure is "time, distance, and shielding." Decreasing the time a patient or technician is exposed does not surprisingly decrease the dose. For a patient, decreasing the distance between the patient and the receiver and decreasing SID decreases the dose. However, decreasing SID results in increased magnification. Increasing the distance between the patient and the x-ray beam for the technician decreases the dose by decreasing exposure to scattered radiation. Radiation exposure is also minimized by filtration, collimation, and lead aprons (shielding). Filters like those made of aluminum positioned within the x-ray tube housing absorb low-energy x-rays of little diagnostic use. At the same time, collimation restricts the x-ray beam itself. Lead aprons and protective barriers also shield operators and patients during image acquisition.

Competencies - The 2015 American Registry of Radiologic Technologists (ARRT) task inventory delineates approximately 131 responsibilities and fields of competency for a staff radiographer (x-ray technician). Notable responsibilities relevant to this topic include:

- Restricting the beam to the anatomical area of interest

- Advocating radiation safety

- Selecting radiographic exposure factors

- Operating fluoroscopic unit and accessories

- Operating electronic imaging and record-keeping devices

- Modifying technical factors to correct for noise in a digital image

- Perform post-processing preparation

- Position the patient to demonstrate the desired anatomy using anatomical landmarks

- Modify exposure factors as appropriate for an individual examination

- Evaluate images for diagnostic quality

- Determine corrective measures to ensure diagnostic quality

- Correction of image artifacts

- Perform routine maintenance on digital equipment

- Positioning patients, x-ray tubes, and image receptors to perform close to 52 unique examinations

Technical Elements of Images Acquisition - Technical acquisition of radiographs depends on the anatomic body part being imaged. Radiology studies are generally comprised of 3 or more views; however, a detailed description of patient positioning and required views for specific radiographic studies is beyond the scope of this topic. In general, musculoskeletal examinations comprise anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views with additional unique views for various body parts such as the Grashey and axillary views of the shoulder or the Judet view of the pelvis. The following represent basic instructions for classic anteroposterior (AP) views of common anatomic studies obtained in radiology with collimation values adapted from the 14th edition of Merril’s atlas of radiographic positions and radiologic procedures:

Hand Radiograph (AP)

- The patient is seated.

- The forearm rests on the table.

- The palm is placed against the receptor.

- Digits are slightly spread.

- The central ray is angled perpendicular to the third MCP joint.

Wrist Radiography (AP)

- The patient is seated.

- The forearm rests on the table.

- The wrist is centered at the level of the receptor.

- The central ray is angled perpendicular to the midcarpal region.

Elbow Radiograph (AP)

- The patient is seated with the arm placed on the table.

- The elbow is extended with the hand supinated.

- The elbow joint is centered at the receptor.

- The central ray is angled perpendicular to the elbow joint.

Shoulder Joint (AP)

- The patient is standing upright or recumbent.

- The glenohumeral joint is centered at the receptor.

- The arm is abducted slightly.

- The palm is placed on the abdomen.

- The central ray is angled perpendicular to the receptor.

- Collimation is adjusted to approximately 24 x 30 cm.

Foot (AP view)

- The patient is positioned in a supine or seated position.

- Knees are flexed with feet separated.

- The plantar surface of the foot is centered at the receptor.

- The central ray is angled 10 degrees posteriorly towards the heel to the 3rd metatarsal base (or perpendicularly).

- Collimate to 2.5 cm on the sides and 2.5 cm beyond the calcaneus and toes.

Ankle (AP view)

- The patient is supine or seated on the table.

- The leg is extended.

- The ankle is centered at the level of the receptor.

- Toes point vertically.

- The central ray is angled perpendicular to the ankle joint (between the malleoli).

- Collimate 2.5 cm on ankle sides and 18 cm along the length.

Knee (AP, Non-weight Bearing)

- The patient is supine with the leg in the extended position.

- The pelvis should not be rotated.

- Center knee to the receptor approximately 1.5 cm below the patella apex.

- Collimate 18 x 24 cm; 2.5 cm beyond sides.

Hip (AP)

- The patient is positioned supine.

- Rotate hip 15-20 degrees medially.

- Center hip at the level of the receptor.

- Collimate 24 x 30 cm.

Chest (posteroanterior)

- The patient is standing or seated in an upright position.

- The back of the hand is placed on the hips.

- Chin is extended.

- Place the top of the receptor 4 to 5 cm above the shoulders.

- The patient should flex their arms with the back of their hands on their hips.

- Ensure full inspiration.

- The central ray is perpendicular to the center of the receptor.

- Collimate 35 x 43 cm.

Abdomen (AP, Supine)

- The patient is placed supine.

- Center receptor at the iliac crests.

- Pubic symphysis should be included.

- The central ray is angled perpendicular to the receptor at the iliac crests.

- Collimate 35 x 43 cm.

Clinical Significance

Standard radiographs remain the most important and frequently used modality in clinical imaging due to the relatively low radiation dose to the patient, low cost, universal availability, and ability to perform portable exams, decreasing the risk to patients not easily transported to radiology. Imaging of the chest is helpful in the diagnosis of various entities such as atelectasis, consolidation seen in pneumonia, pulmonary edema and hemorrhage, and primary lung malignancies or metastatic disease.[12] Chest radiographs are also used to investigate other clinical entities such as pneumothorax, emphysema, cardiomegaly, fibrotic processes, diaphragmatic hernias, and empyema.

Although the role of standard radiographs is limited in abdominal imaging, abdominal radiographs can be evaluated for free air, small bowel obstruction, stool burden, and abnormal calcifications(such as in the setting of obstructing ureteroliths and gallstones).[13] Abdominal radiographs can also play a role in evaluating portal venous gas, pneumobilia, emphysematous cystitis, and pyelonephritis. Chest and abdominal radiographs are also commonly obtained to assess the placement and positioning of various support devices such as vascular catheters, chest tubes, enteric tubes, and surgical drains.

Perhaps the most important role of radiographs in the clinical setting is its role in musculoskeletal imaging. Standard radiographs evaluate for arthritis (degenerative and inflammatory processes), bone tumors (lytic and sclerotic primary and metastatic disease), infection, and fractures. Radiography also plays an important role in mammography with its use in screening and evaluation for breast cancer. Fluoroscopy in interventional radiology plays an important role in evaluating various vascular structures (arterial and venous), the biliary system, and various cavities and spaces of the human body using contrast agents. Fluoroscopy is also used for image-guided injections of the musculoskeletal system (therapeutic and diagnostic joint injections).

Although CTs have gained a strong role in clinical imaging, standard radiographs remain the mainstay in pediatric imaging due to their comparatively lower radiation dose. Radiographs evaluate congenital malformations of various organs (and their respective complications), including the heart, lungs, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems. The clinical uses of radiography in musculoskeletal imaging in pediatric patients mirror those of adults, with important applications in pediatric-specific pathologic entities such as hip dysplasia, child abuse, and Salter-Harris fractures.[14]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Successfully obtaining radiology studies is a complex, interdisciplinary, multifaceted process. First, the ordering provider must decide on the appropriate imaging study to evaluate a given patient to establish an appropriate and accurate diagnosis. Then, they must communicate the history and differential diagnosis and request the study to the radiology department (technician and radiologist). Subsequently, the radiology technician must obtain the correct study, employ the correct technique at a diagnostic level, and promptly provide the images to the radiologist. Finally, the radiologist is responsible for interpreting the images and providing/communicating a clear, concise, and accurate report to the ordering provider. Not surprisingly, this complex, multi-step process is a common issue that results in medical errors. Various studies have explored the important role of interprofessional communication in patient care and outcomes. One study determined that non-medical radiology staff expressed notable difficulty in oral and written inter-professional communication with other healthcare team members.[15]

This often results from unclear language or differences in terminology used between professions, possibly leading to inappropriate studies being performed or inaccurate clinical information being passed on to the radiologist. Lack of feedback from clinicians and radiologists, especially due to decreased face-to-face communication, was also described as a possible reason for difficulties in providing patient care. Clear communication between technologists, nurses, and physicians is important in obtaining diagnostic images with an adequate field of view and decreasing medical errors. A 2009 study by Verhovsek et al determined that radiology technicians often had trouble communicating adequately with nurses and surgeons. Several studies have investigated the communication of the ordering provider with the Department of Radiology. One study found that 24% to 41% of orders failed to identify the target condition leading to the request.[16] Additional studies showed the clinical history inadequate or missing the current diagnosis/indication in 7% to 31% of cases.[17][18][19]

Radiologists' communication of critical results is also an important medicolegal issue. One report indicates that 83% of primary care providers are dissatisfied with the communication of results (laboratory, pathology, and radiology).[20] In an American College of Radiology survey, 25% of respondents indicated a communication failure, resulting in at least 1 lawsuit. This communication failure may partly be related to the lack of information on the requisition, as 1 study showed the ordering provider's name missing in 14% of cases and the provider's pager number missing in 84% of cases.[21] Imaging studies are an important component of patient evaluation and diagnosis. It is a complex process involving multiple moving parts and numerous healthcare providers from various departments. It requires a high commitment to interprofessional skills to decrease medical errors and improve patient outcomes.