Learning Outcome

- Recall the cause of mumps

- Describe the presentation of mumps

- Summarize the treatment of mumps

- List the nurse's role in the management of mumps

Mumps is a contagious viral illness and at one time was a very common childhood disease. With the implementation of widespread vaccination, the incidence of mumps in the population has decreased substantially. Mumps infection typically presents with a prodrome of headache, fever, fatigue, anorexia, malaise followed by the classic hallmark of the disease, parotitis. The disease is more often self-limited with individuals experiencing a full recovery.[1]

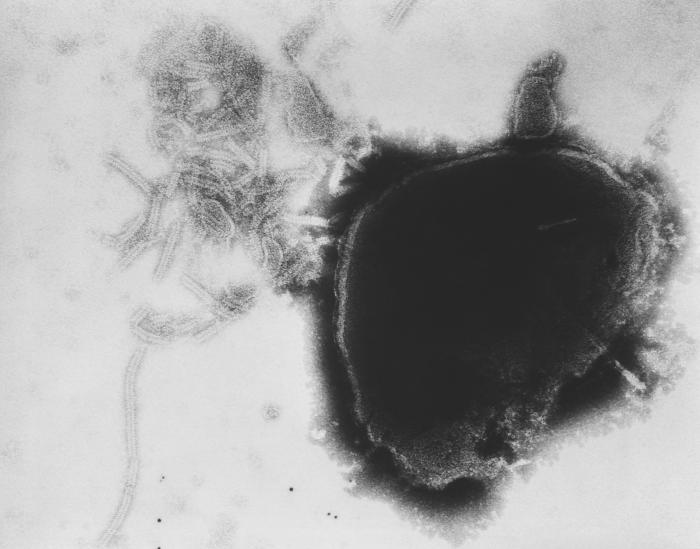

Mumps is a single-stranded RNA paramyxovirus. There is only one known serotype of the mumps virus. Nucleoprotein, phosphoprotein, and polymerase together with the genomic RNA replicate the virus forming the ribonucleocapsid. A host-derived lipid bilayer surrounds the ribonucleocapsid. Within this lipid bilayer are viral neuraminidase and fusion proteins which allow cell binding and entry of the virus. These fusion complexes are the main targets of virus-neutralizing antibodies. The virus itself is a stable virus unable to combine. This makes antigenic shift unlikely.[2][3] This inability in genetic drift allows vaccination to most typically confer long-lasting immunity in individuals.[4]

Mumps is endemic worldwide with epidemic outbreaks occurring approximately every five years in unvaccinated regions. The mumps virus is highly infectious and transmissible through direct contact with respiratory droplets, saliva, and household fomites. Up to one-third of individuals infected exhibit no symptoms, but are contagious. Introduction of the mumps vaccine in the year 1967 resulted in a 99.8% reduction of documented cases in the United States by 2001.[1] Several confounding factors caused recent outbreaks in the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States during the early 2000s. A combination of waning vaccine immunity over time, the continuing global epidemic of mumps in non-vaccinated populations, and the absence of a wild-type virus to boost immune responses within vaccinated individuals. These factors coupled with individuals living in close quarters such as college dormitories allow the spread of a respiratory virus such as mumps to cause an outbreak.[5][1]

The prodrome of the mumps virus includes nonspecific symptoms such as fever, malaise, headache, myalgias, and anorexia shortly followed by parotitis in the following days. Mumps parotitis is the most common manifestation of the virus occurring in over 70% of infections. Parotid swelling is usually bilateral, but unilateral swelling can occur[1]. Parotid swelling presents as painful inflammation of the area between the earlobe and the angle of the mandible. The mucosa of Stenson’s duct is often red and swollen along with the involvement of the submaxillary and submandibular glands.[6][7] Glandular inflammation most often presents but then subsides within one week.[8] Recurrent sialadenitis is a frequent complication of parotitis. Mumps during pregnancy is unknown to lead to premature birth, low birth weight, or fetal malformation.[1][9][10][11][12] Orchitis is the next most common manifestation of mumps which leads to painful swelling, enlargement, and tenderness of the testes which is most often bilateral. Testicular atrophy develops in one half of those affected. Sterility and subfertility after mumps infection is rare and occurs in less than 15% of cases.[1][7][13][14][15] Oophoritis is also rare amongst infected females with less than 5% developing infertility or pre-menopause.[1] Neurological manifestations include meningitis, encephalitis, transverse myelitis, Guillan-Bare syndrome, cerebellar ataxia, facial palsy, and hydrocephalus. Neurological complications are typically self-resolving, and there is a low incidence of morbidity and mortality.[16] Additional systemic rare complications include pancreatitis, myocarditis, thyroiditis, nephritis, hepatic disease, arthritis, keratitis, and thrombocytopenic purpura.[17][18][19][20]

Clinical observation and laboratory testing confirm a mumps infection. Not all mumps cases classically display orchitis and parotitis and individuals may present heterogeneously. During an outbreak, the diagnosis is clinical in cases of parotid swelling with a history of exposure. When the local incidence is low other causes of parotitis warrant investigation. Laboratory testing is not routinely necessary to confirm a mumps viral infection, but in equivocal cases testing for other viral infections such as HIV, influenza, and para-influenza is necessary. Staphylococcus aureus is not an uncommon cause of suppurative parotitis. Recurrent parotid swelling of unknown etiology warrants an investigation for ductal calculi and malignancy. A viral mumps infection in the absence of parotid swelling and/or salivary gland involvement may present with symptoms of visceral and CNS predominance. In these cases, diagnosis relies on positive antibody titers and virus culture from oral secretions, urine, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Laboratory confirmation techniques include reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and serum IgM antibodies. RT-PCR is for serum and oral secretions. RT-PCR specimens additionally are for viral cultures. At the initial presentation of an individual suspected of mumps infection collect 2 specimens: a buccal or oral swab for RT-PCR and also an acute phase serum specimen for IgM antibody, IgG antibody, and serum viral RT-PCR. Obtain oral specimens within three days of parotid gland swelling and no later than 8 days after the start of symptoms. The IgM response may not be detectable for up to five days after the onset of symptoms. Incorrect collection of acute-phase samples lead to false-negative IgM and RT-PCR tests. When this occurs collect repeat samples 5 to 10 days after symptom onset to yield positive results. Laboratory confirmation of an acute viral infection in individuals with prior vaccination is difficult. This occurs due to multiple reasons: IgM antibodies are negative in a large number of patients, and RT-PCR results may be falsely negative. The disease is a Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reportable illness with most states requiring reporting in 1 to 3 days.[21][22][23][8]

Mumps is typically a benign illness that is self-resolving. [1] Treatment is supportive care for each presenting symptom. Analgesic medications and cold or warm compresses for parotid swelling are beneficial. Treat testicular swelling and tenderness with elevation and cold compression.[24] There is no proven benefit for glucocorticoid use and surgical drainage of mumps parotitis and orchitis. Consider a therapeutic lumbar injection to relieve a headache associated with aseptic meningitis due to mumps viral infection.[25] Mumps immune-globulin (Ig) is not effective in preventing mumps and not recommend for treatment nor post-exposure prophylaxis in patients.[26] Common practice is to administer the mumps vaccine as part of a trivalent measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), commonly known as the abbreviated MMR vaccine. The vaccine is administered in 2 doses with children most often receiving the first dose around 1 year of age and the second dose typically given between the ages of 4 to 6. Immunity from mumps results from the development of neutralizing antibodies. Seroconversion occurs in most recipients, and post-vaccination immunity is around 80% after the first dose and 90% after the second dose. In 2018, the CDC recommended that individuals vaccinated prior with 2 doses of mumps vaccine are at increased for a population outbreak and should receive a third dose (for example, college students). [22][23][8][27][4][28] Prevention with vaccination is the most practical and effective control measure. The mumps vaccine is a live attenuated virus. It should not be administered to pregnant women and women should wait 4 weeks after MMR vaccination to become pregnant. Vaccinate women who are breastfeeding along with children and other household contacts of pregnant women. Individuals who suffered life-threatening allergic reactions to components of the vaccine or those with significant immunosuppression are not candidates for vaccination. This includes patients with AIDS, leukemia, lymphoma, generalized malignancy, and those receiving treatment with chemotherapy, radiation, or corticosteroid therapy. Vaccinate household contacts to those with severe immunosuppression. Do not vaccinate AIDS or HIV patients who have signs of immunosuppression, but vaccinate HIV patients who do not have laboratory evidence of immunosuppression.[4] Isolate patient infected with mumps and place on droplet precautions. The CDC recommends isolation for 5 days after the onset of parotid swelling.[23]

Normal vitals

No facial swelling

Normal appetite

An Interprofessional Approach to Mumps

As practitioners in this era of the anti-vaccination movement, advocating the benefits of the MMR vaccine is vital. The resurgence of mumps outbreaks is preventable with proper patient education by practitioners from all spectrums of practice. Nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare workers should repeatedly encourage parents to get their children vaccinated against mumps. While the infection is not life-threatening, it can have considerable morbidity if the testes or ovaries are affected.

As practitioners in this era of the anti-vaccination movement, advocating the benefits of the MMR vaccine is vital. The resurgence of mumps outbreaks is preventable with proper patient education by practitioners from all spectrums of practice. Nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare workers should repeatedly encourage parents to get their children vaccinated against mumps. Today, school nurses and local public health officials now offer vaccination, unless otherwise contraindicated.

When a mumps case is diagnosed, it has to be reported to the local authorities. The child has to be educated on hand washing and the need for isolation until the symptoms subside. The public health nurse should follow these patients for complications and refer all patients with symptoms to the primary care provider. Patients and caregivers need to be educated that the vaccine is safe and adverse reactions are rare.

While the infection is not life-threatening, it can have considerable morbidity if the testes or ovaries are affected.

Paramyxovirus Virion Under Transmission, Electron Microscope. The image displays the viral nucleocapsid of a paramyxovirus virion as visualized under a transmission electron microscope.

Fred Murphy, MD, Public Health Image Library, Public Domain, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Lam E, Rosen JB, Zucker JR. Mumps: an Update on Outbreaks, Vaccine Efficacy, and Genomic Diversity. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2020 Mar 18:33(2):. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00151-19. Epub 2020 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 32102901]

Almansour I. Mumps Vaccines: Current Challenges and Future Prospects. Frontiers in microbiology. 2020:11():1999. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01999. Epub 2020 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 32973721]

Su SB, Chang HL, Chen AK. Current Status of Mumps Virus Infection: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Vaccine. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020 Mar 5:17(5):. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051686. Epub 2020 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 32150969]

Wu H, Wang F, Tang D, Han D. Mumps Orchitis: Clinical Aspects and Mechanisms. Frontiers in immunology. 2021:12():582946. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.582946. Epub 2021 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 33815357]

Marin M, Marlow M, Moore KL, Patel M. Recommendation of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for Use of a Third Dose of Mumps Virus-Containing Vaccine in Persons at Increased Risk for Mumps During an Outbreak. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018 Jan 12:67(1):33-38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6701a7. Epub 2018 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 29324728]

Hviid A, Rubin S, Mühlemann K. Mumps. Lancet (London, England). 2008 Mar 15:371(9616):932-44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60419-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18342688]

Shepersky L, Marin M, Zhang J, Pham H, Marlow MA. Mumps in Vaccinated Children and Adolescents: 2007-2019. Pediatrics. 2021 Dec 1:148(6):. pii: e2021051873. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-051873. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34814181]

Shah M, Quinlisk P, Weigel A, Riley J, James L, Patterson J, Hickman C, Rota PA, Stewart R, Clemmons N, Kalas N, Cardemil C, Iowa Mumps Outbreak Response Team. Mumps Outbreak in a Highly Vaccinated University-Affiliated Setting Before and After a Measles-Mumps-Rubella Vaccination Campaign-Iowa, July 2015-May 2016. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018 Jan 6:66(1):81-88. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix718. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29020324]

RUSSELL RR, DONALD JC. The neurological complications of mumps. British medical journal. 1958 Jul 5:2(5087):27-30 [PubMed PMID: 13546635]

Dayan GH, Quinlisk MP, Parker AA, Barskey AE, Harris ML, Schwartz JM, Hunt K, Finley CG, Leschinsky DP, O'Keefe AL, Clayton J, Kightlinger LK, Dietle EG, Berg J, Kenyon CL, Goldstein ST, Stokley SK, Redd SB, Rota PA, Rota J, Bi D, Roush SW, Bridges CB, Santibanez TA, Parashar U, Bellini WJ, Seward JF. Recent resurgence of mumps in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2008 Apr 10:358(15):1580-9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706589. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18403766]

Siegel M, Fuerst HT, Peress NS. Comparative fetal mortality in maternal virus diseases. A prospective study on rubella, measles, mumps, chicken pox and hepatitis. The New England journal of medicine. 1966 Apr 7:274(14):768-71 [PubMed PMID: 17926883]

Enders M, Rist B, Enders G. [Frequency of spontaneous abortion and premature birth after acute mumps infection in pregnancy]. Gynakologisch-geburtshilfliche Rundschau. 2005 Jan:45(1):39-43 [PubMed PMID: 15644639]

McNabb SJ, Jajosky RA, Hall-Baker PA, Adams DA, Sharp P, Anderson WJ, Javier AJ, Jones GJ, Nitschke DA, Worshams CA, Richard RA Jr, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Summary of notifiable diseases --- United States, 2005. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2007 Mar 30:54(53):1-92 [PubMed PMID: 17392681]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for isolation of persons with mumps. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2008 Oct 10:57(40):1103-5 [PubMed PMID: 18846033]

Brook I. Diagnosis and management of parotitis. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1992 May:118(5):469-71 [PubMed PMID: 1571113]

Wright WF, Pinto CN, Palisoc K, Baghli S. Viral (aseptic) meningitis: A review. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2019 Mar 15:398():176-183. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.050. Epub 2019 Jan 31 [PubMed PMID: 30731305]

Trojian TH, Lishnak TS, Heiman D. Epididymitis and orchitis: an overview. American family physician. 2009 Apr 1:79(7):583-7 [PubMed PMID: 19378875]

the Association for the Study of Infectious Disease. A retrospective survey of the complications of mumps. The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners. 1974 Aug:24(145):552-6 [PubMed PMID: 4465449]

Gray JA. Mumps. British medical journal. 1973 Feb 10:1(5849):338-40 [PubMed PMID: 4685627]

Barskey AE, Schulte C, Rosen JB, Handschur EF, Rausch-Phung E, Doll MK, Cummings KP, Alleyne EO, High P, Lawler J, Apostolou A, Blog D, Zimmerman CM, Montana B, Harpaz R, Hickman CJ, Rota PA, Rota JS, Bellini WJ, Gallagher KM. Mumps outbreak in Orthodox Jewish communities in the United States. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Nov 1:367(18):1704-13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202865. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23113481]

Zamir CS, Schroeder H, Shoob H, Abramson N, Zentner G. Characteristics of a large mumps outbreak: Clinical severity, complications and association with vaccination status of mumps outbreak cases. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2015:11(6):1413-7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1021522. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25874726]

Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Marchione P, Debalini MG, Demicheli V. Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2021 Nov 22:11(11):CD004407. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5. Epub 2021 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 34806766]

McLean HQ, Fiebelkorn AP, Temte JL, Wallace GS, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of measles, rubella, congenital rubella syndrome, and mumps, 2013: summary recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2013 Jun 14:62(RR-04):1-34 [PubMed PMID: 23760231]

Ogbuanu IU, Kutty PK, Hudson JM, Blog D, Abedi GR, Goodell S, Lawler J, McLean HQ, Pollock L, Rausch-Phung E, Schulte C, Valure B, Armstrong GL, Gallagher K. Impact of a third dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine on a mumps outbreak. Pediatrics. 2012 Dec:130(6):e1567-74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0177. Epub 2012 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 23129075]

Nelson GE, Aguon A, Valencia E, Oliva R, Guerrero ML, Reyes R, Lizama A, Diras D, Mathew A, Camacho EJ, Monforte MN, Chen TH, Mahamud A, Kutty PK, Hickman C, Bellini WJ, Seward JF, Gallagher K, Fiebelkorn AP. Epidemiology of a mumps outbreak in a highly vaccinated island population and use of a third dose of measles-mumps-rubella vaccine for outbreak control--Guam 2009 to 2010. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2013 Apr:32(4):374-80. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318279f593. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23099425]

Cardemil CV, Dahl RM, James L, Wannemuehler K, Gary HE, Shah M, Marin M, Riley J, Feikin DR, Patel M, Quinlisk P. Effectiveness of a Third Dose of MMR Vaccine for Mumps Outbreak Control. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Sep 7:377(10):947-956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703309. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28877026]

Abedi GR, Mutuc JD, Lawler J, Leroy ZC, Hudson JM, Blog DS, Schulte CR, Rausch-Phung E, Ogbuanu IU, Gallagher K, Kutty PK. Adverse events following a third dose of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine in a mumps outbreak. Vaccine. 2012 Nov 19:30(49):7052-8. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.09.053. Epub 2012 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 23041123]

Seither R, Yusuf OB, Dramann D, Calhoun K, Mugerwa-Kasujja A, Knighton CL. Coverage with Selected Vaccines and Exemption from School Vaccine Requirements Among Children in Kindergarten - United States, 2022-23 School Year. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2023 Nov 10:72(45):1217-1224. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7245a2. Epub 2023 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 37943705]

Barbel P, Peterson K, Heavey E. Mumps makes a comeback: What nurses need to know. Nursing. 2017 Jan:47(1):15-17. doi: 10.1097/01.NURSE.0000510761.53098.22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28027128]