Learning Outcome

- List the causes of infectious mononucleosis

- Describe the presentation of infectious mononucleosis

- Summarize the treatment of infectious mononucleosis

- Recall the nursing management of a patient with infectious mononucleosis

Mononucleosis classically presents with fever, lymphadenopathy, and tonsillar pharyngitis. The term “infectious mononucleosis” was first used in the 1920s to describe a group of students with a similar pharyngeal illness and blood laboratory findings of lymphocytosis and atypical mononuclear cells. It was only later that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) was established as the cause of mononucleosis after an exposed healthcare worker developed a positive heterophile test.[1][2]

The cause of mononucleosis is the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). EBV is a type of herpesvirus spread by contact, typically with salivary secretions. The duration of oral shedding is not entirely clear, but high levels of shedding can continue for a median of 6 months after illness onset. Transmission is generally person-to-person, but EBV is not considered a highly contagious disease. [3]

It is estimated that up to 95% of adults in the world are eventually seropositive to EBV. Therefore, EBV is widely disseminated in all population groups. The traditional age group where peak incidence is noted, however, is in 15 to 24-year olds. Classically, the symptomatic infection is in adolescents, which is why laypersons may refer to the infection as the “kissing disease.” Mononucleosis is uncommon in adults: approximately 2% of all pharyngeal disease in adults is attributable to this disease. Adults are generally not susceptible to clinical illness because of previous exposure. In the United States, clinically evident infection occurs at rates estimated at 30 times higher in whites than in blacks. One explanation for this disparity is that if acquired at a young (childhood) age, EBV is often subclinical. This would suggest earlier EBV exposures in blacks, and a higher frequency of asymptomatic infection as young children. [1][4]

Fever, sore throat, fatigue, and tender lymph nodes are classic findings on history-taking in infected individuals with mononucleosis. The classical triad is fever, pharyngitis, and lymphadenopathy. Additional complaints include a headache, general malaise, and poor oral intake. Unfortunately for some, fatigue can be persistent for months in select individuals. Lymphadenopathy is more common in the posterior cervical region. The pharyngitis is often heralded with tonsillar exudates. Petechial lesions on the palate occur infrequently. Also, splenomegaly is a key finding on physical in up to half of patients with active clinical mononucleosis. Identification is important in patients prone to future injury, e.g., active sports participants. Skin examination in some patients may infrequently reveal a nonspecific, generalized maculopapular rash. This is separate from the antibiotic-induced rash discussed below.

As always, initial evaluation should include airway assessment to determine that the airway is patent and there is no impending occlusion or compromise. In rare instances, abscess or edema can impede proper maintenance of the airway. Also, determination of hemodynamic stability is important to rule out concomitant splenic injury or rupture in the acute illness of mononucleosis. Laboratory evaluation most commonly will reveal lymphocytosis, with a lymphocyte differential often greater than 50%. Atypical lymphocytosis of greater than 10% can be seen on blood smear. A general leukocytosis and occasionally thrombocytopenia may also be appreciated. Imaging is generally not needed in the evaluation of mononucleosis. The monospot (or heterophile antibody) test for mononucleosis is the diagnostic test of choice and is nearly 100% specific for the disease. The sensitivity of this test is closer to 85%. If the patient is early in the illness, the test may be falsely negative, and it should be repeated later during the course of the disease. If the diagnosis is unclear, the patient should also undergo evaluation for streptococcal infection by rapid antigen testing or throat culture.[5][6][7]

Treatment is generally supportive for mononucleosis. Antipyretics and anti-inflammatory medications help to treat fever, sore throat, and the general fatigue seen in this illness. Hydration, rest, and good nutritional intake should also be encouraged. Corticosteroids are not generally recommended in the routine treatment of mononucleosis because of concerns with immunosuppression; however, in cases of airway obstruction, corticosteroids (and possible otolaryngology consultation) are indicated along with appropriate airway management. In instances where antibiotics have been inappropriately administered in patients with mononucleosis, a generalized maculopapular rash may develop. Classically, this is after administration of amoxicillin but can be seen with other antibiotics as well. All athletes should avoid sports during the early course of the illness (approximately three weeks) because of the splenic enlargement was seen in approximately 50% of patients with mononucleosis and the associated risk of splenic rupture.[8][9]

The majority of individuals who develop mononucleosis have an excellent outcome. The disorder is self limited and recovery is common in 2-4 weeks. The rare patient may develop a splenic rupture but even these cases are now managed conservatively as long as the patient remains hemodynamically stable.[10][11] (Level V)

Once a patient has been diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis, the nurse and primary care provider should educate the patient on potential complications and the course of the illness. The patient should be told to avoid all physical activity for at least 4-6 weeks to minimize the risk of splenic rupture. The patient should be told about the signs and symptoms of splenic rupture and when to return to the hospital. All patients should be told about the need to follow up until the symptoms subside and permission to return to physical activity. [12][13](Level V)

Outcomes

The majority of individuals who develop mononucleosis have an excellent outcome. The disorder is self limited and recovery is common in 2-4 weeks. The rare patient may develop a splenic rupture but even these cases are now managed conservatively as long as the patient remains hemodynamically stable.[10][11] (Level V)

Once a patient has been diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis, the nurse practitioner and primary care provider should provide coordinated education of the patient and family on potential complications and the course of the illness. The patient should be told to avoid all physical activity for at least 4-6 weeks to minimize the risk of splenic rupture. The patient should be told about the signs and symptoms of splenic rupture and when to return to the hospital. All patients should be told about the need to follow up until the symptoms subside and permission to return to physical activity. The pharmacist should educate the patient on supportive care and the need to remain hydrated. Finally, all clinicians looking after patients with mononucleosis should be aware of the potential complications, and make the appropriate referral to the specialist when symptoms arise.[12][13](Level V)

The diagnostic test of choice for mononucleosis is the heterophile antibody (monospot) test. This can be occasionally falsely negative in early disease and require repeat testing later in the course of the illness.

The most important entity to exclude from the differential diagnosis is primary HIV infection.

Splenic rupture is a rare complication in mononucleosis but can be potentially life-threatening if not diagnosed in a timely fashion. Consider it on the differential in the patient with classic mononucleosis, abdominal pain, and anemia. Airway obstruction is another rarely seen adverse outcome that requires immediate treatment and management.

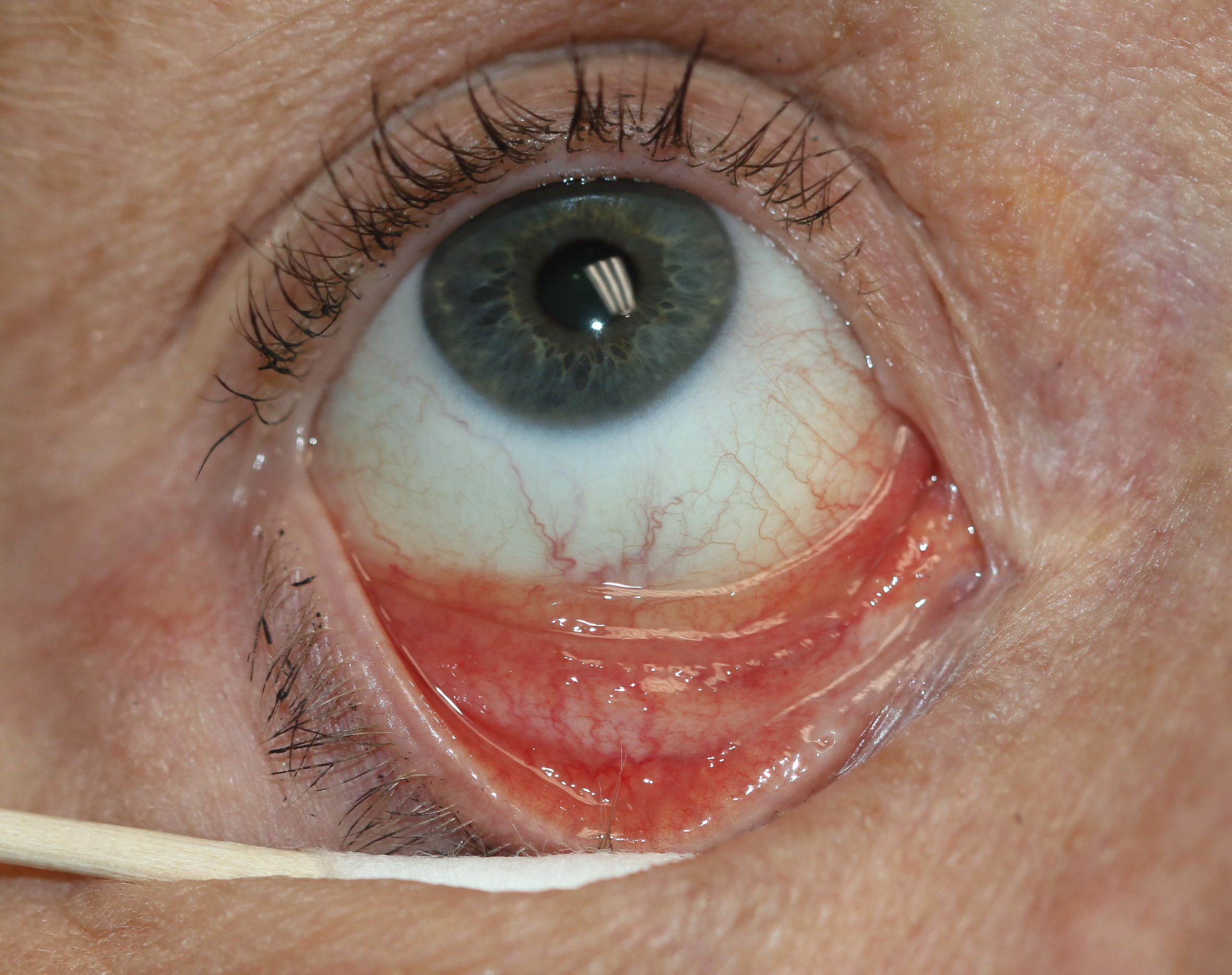

Follicular Conjunctivitis. Inflammation is noted with viral infections like herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus infection, infectious mononucleosis, and chlamydial infections, as well as in reaction to topical medications and molluscum contagiosum. Follicular conjunctivitis has been described in patients with COVID-19. The inferior and superior tarsal conjunctiva and the fornices show gray-white elevated swellings about 0.5 to 1 mm in diameter and have a velvety appearance.

Contributed by Prof. BCK Patel MD, FRCS

Smatti MK, Al-Sadeq DW, Ali NH, Pintus G, Abou-Saleh H, Nasrallah GK. Epstein-Barr Virus Epidemiology, Serology, and Genetic Variability of LMP-1 Oncogene Among Healthy Population: An Update. Frontiers in oncology. 2018:8():211. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00211. Epub 2018 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 29951372]

Stemberger M, Jung C, Bogner JR. [Mononucleosis: a disease with three different etiologies]. MMW Fortschritte der Medizin. 2018 May:160(10):44-48. doi: 10.1007/s15006-018-0582-1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29855902]

Correia S, Bridges R, Wegner F, Venturini C, Palser A, Middeldorp JM, Cohen JI, Lorenzetti MA, Bassano I, White RE, Kellam P, Breuer J, Farrell PJ. Sequence Variation of Epstein-Barr Virus: Viral Types, Geography, Codon Usage, and Diseases. Journal of virology. 2018 Nov 15:92(22):. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01132-18. Epub 2018 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 30111570]

Downham C, Visser E, Vickers M, Counsell C. Season of infectious mononucleosis as a risk factor for multiple sclerosis: A UK primary care case-control study. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders. 2017 Oct:17():103-106. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.07.009. Epub 2017 Jul 8 [PubMed PMID: 29055437]

Burnard S, Lechner-Scott J, Scott RJ. EBV and MS: Major cause, minor contribution or red-herring? Multiple sclerosis and related disorders. 2017 Aug:16():24-30. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2017.06.002. Epub 2017 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 28755681]

Womack J, Jimenez M. Common questions about infectious mononucleosis. American family physician. 2015 Mar 15:91(6):372-6 [PubMed PMID: 25822555]

Koester TM, Meece JK, Fritsche TR, Frost HM. Infectious Mononucleosis and Lyme Disease as Confounding Diagnoses: A Report of 2 Cases. Clinical medicine & research. 2018 Dec:16(3-4):66-68. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2018.1419. Epub 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30166498]

Kolesnik Y, Zharkova T, Rzhevskaya O, Kvaratskheliya T, Sorokina O. [CLINICAL AND IMMUNOLOGICAL CRITERIA FOR THE ADVERSE COURSE OF INFECTIOUS MONONUCLEOSIS IN CHILDREN]. Georgian medical news. 2018 May:(278):132-138 [PubMed PMID: 29905559]

Li Y, George A, Arnaout S, Wang JP, Abraham GM. Splenic Infarction: An Under-recognized Complication of Infectious Mononucleosis? Open forum infectious diseases. 2018 Mar:5(3):ofy041. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy041. Epub 2018 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 29577060]

Vogler K, Schmidt LS. [Clinical manifestations of Epstein-Barr virus infection in children and adolescents]. Ugeskrift for laeger. 2018 May 14:180(20):. pii: V09170644. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29761777]

Dunmire SK, Verghese PS, Balfour HH Jr. Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 2018 May:102():84-92. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2018.03.001. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29525635]

Olympia RP. School Nurses on the Front Lines of Medicine: A Student With Fever and Sore Throat. NASN school nurse (Print). 2016 May:31(3):150-2. doi: 10.1177/1942602X16642252. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27091630]

Grimes RM, Hardwicke RL, Grimes DE, DeGarmo DS. When to consider acute HIV infection in the differential diagnosis. The Nurse practitioner. 2016 Jan 16:41(1):. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000475371.63182.b7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26678418]

Aslan N, Watkin LB, Gil A, Mishra R, Clark FG, Welsh RM, Ghersi D, Luzuriaga K, Selin LK. Severity of Acute Infectious Mononucleosis Correlates with Cross-Reactive Influenza CD8 T-Cell Receptor Repertoires. mBio. 2017 Dec 5:8(6):. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01841-17. Epub 2017 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 29208744]

De Paor M, O'Brien K, Fahey T, Smith SM. Antiviral agents for infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2016 Dec 8:12(12):CD011487. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011487.pub2. Epub 2016 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 27933614]