Learning Outcome

- Recall the cause of influenza

- Describe the symptoms of influenza

- Summarize the treatment of influenza

- List the nursing care plans of a patient with influenza

Influenza is a communicable viral disease that affects the upper and lower respiratory tract. A wide spectrum of influenza viruses causes it. Some of these viruses can infect humans, and some are specific to different species. These viruses are transmissible through respiratory droplets expelled from the mouth and respiratory system during coughing, talking, and sneezing. The influenza viruses can be transmitted by touching inanimate objects soiled with the virus and touching the nose or eye. Influenza can be transmitted before the patient is symptomatic and until 5 to 7 days after infection. After infection, it takes a few days for most of the healthy patients to recover fully, but complications that include pneumonia and death are common in certain high-risk groups. These groups include young children, the elderly, immunocompromised, and pregnant females. Symptoms of influenza include a runny nose, high fever, cough, and sore throat. Influenza spreads rapidly and efficiently in seasonal epidemics. Flu epidemics occur every autumn and winter in temperate regions and affect a significant portion of adults and children, but seasons differently impact age groups and severity. [1][2][3][4]

There are four types of influenza viruses, A, B, C, and D. Influenza types A and B cause human infection annually during the epidemic season. Influenza A has several subtypes according to the combination of hemagglutinin (H) and the neuraminidase (N) proteins that are expressed on the surface of the viruses. There are 18 different hemagglutinin subtypes and 11 different neuraminidase subtypes (H1-18 and N1-11). Influenza A viruses can be characterized by the H and N types such as H1N1 and H3N2. Influenza B viruses are classified into lineages and strains. Influenza B viruses that have circulated in recent influenza seasons belong to one of two lineages, influenza B Yamagata and influenza B Victoria. Influenza viruses have receptors responsible for making them species-specific.

Animal influenza viruses can cause infections in humans if the antigenic characters of the virus change. When this happens, transmission from person-to-person is usually inefficient. Influenza pandemics like 1918 and 2009 can occur if the transmission from person-to-person becomes efficient. Avian influenza, or bird flu, is an infectious disease of birds caused by a variety of influenza A viruses, including A(H5N1), A(H5N8), and H7N9 viruses. These viruses are worrisome as they can change to develop the ability for transmissibility from person-to-person and start a severe pandemic. A good example of animal origin influenza is the 2009 pandemic influenza, which is an animal influenza virus that likely started in South America in early 2009 and developed the ability to spread from person-to-person and spread globally. [5][6]

Researchers isolated Influenza A in 1933, seven years later, they isolated Influenza B. Influenza viruses in certain geographic regions of the northern and southern hemispheres are called an influenza epidemic which occurs every year during the winter seasons. The severity, length of influenza, and age groups that are highly impacted, and complication rates such as hospitalizations and deaths differ significantly during different influenza seasons. When H3N2 viruses predominate, the season tends to be more severe, especially among children and the elderly. The World Health Organization (WHO) conducts global influenza virologic surveillance that indicates influenza viruses are isolated every month from humans in a geographic region. In temperate regions, influenza activity peaks during the winter months. In the Northern Hemisphere, influenza outbreaks and epidemics typically occur between October and March, whereas in the Southern Hemisphere, influenza activity occurs between April and August. In the tropical belt, influenza circulates year-round.

The clinical presentation of influenza ranges between mild to severe depending on the age, comorbidities, vaccination status, and natural immunity to the virus. Usually, patients who received the seasonal vaccine present with milder symptoms, and they are less likely to develop complications.

Signs and symptoms of influenza in mild cases include a cough, fever, sore throat, myalgia, headache, runny nose, and congested eyes. A frontal or retro-orbital headache is a common presentation with selected ocular symptoms that include photophobia and pain with different qualities. The cause of ocular pain is related to the viral tropism that is associated with certain types and subtypes. Severe cases may progress to shortness of breath, tachycardia, hypotension, and need for supportive respiratory interventions in as little as 48 hours.

Diagnosis of influenza can be reached clinically, especially during the influenza season. Most of the cases will recover without medical treatment, and they would not need a laboratory test for the diagnosis. In high-risk cases, initiation of treatment should not be delayed until test results are obtained. Influenza laboratory tests should be ordered for cases where testing would inform clinical action or public health interventions such as the outbreak situations where the diagnosis of the causative agent is necessary for therapeutic and prophylactic recommendations.

Laboratory tests available for diagnosis of influenza are rapid antigen detection, a rapid molecular assay for the detection of viral RNA, immunofluorescence direct and indirect antibody staining for detection of viral antigen, real-time PCR test, and cell culture.

All the rapid tests are associated with low sensitivity and a high rate of false positives. A chest x-ray should be obtained in patients with pulmonary symptoms to exclude bacterial pneumonia.

Influenza infection is self-limited and mild in most healthy individuals who do not have other comorbidities. No antiviral treatment is needed during mild infections in healthy individuals. Antiviral medications can be used to treat or prevent influenza infection, especially during outbreaks in healthcare settings such as hospitals and residential institutions. Oseltamivir, zanamivir, and peramivir belong to the neuraminidase inhibitors family and can be used for the treatment of influenza A and B. The adamantanes antiviral family has two medications, amantadine, and rimantadine. Amantadine and rimantadine are effective against influenza A, but not influenza B. During recent influenza seasons, high rates of resistance have been identified in influenza A for the adamantanes antivirals, and they are not recommended for treatment or prophylaxis against influenza A. Resistance to the neuraminidase inhibitors has been low in recent influenza seasons, but the virus may mutate and develop resistance at any time. Resistance can develop in some patients following treatment, especially in immunocompromised patients. Oseltamivir can be used for chemoprophylaxis for individuals one year and older in cases of outbreaks and exposure in high-risk groups. The side effects of oseltamivir include skin reactions that might be severe and sporadic transient neuropsychiatric events; these side effects form a barrier to the use of oseltamivir in the elderly and individuals that are at higher risk of developing these side effects. The only contraindication to zanamivir is an allergy to eggs.[6][7][8][9]

Vaccination is highly recommended at the start of the winter season. The flu vaccine recommendations include:

While the flu vaccine is not 100% effective, it can lower the intensity and duration of symptoms in most people. Individuals who have lung disease, diabetes, chronic illnesses, the elderly, and children should get the flu vaccine as it can prevent admission to the hospital. Every year, hundreds of individuals are admitted to the hospital, and tragically, some do die from the flu.[10] (Level 5)

The prevention and treatment of influenza are with an interprofessional team that includes a nurse practitioner, primary care provider, internist, an emergency department physician, and an infectious disease specialist. The key is patient educations. All patients should be encouraged to get the annual flu vaccine that is available in November of each year. While the flu vaccine is not 100% effective, it can lower the intensity and duration of symptoms in most people. Individuals who have lung disease, diabetes, chronic illnesses, the elderly, and children should get the flu vaccine as it can prevent admission to the hospital. Every year, hundreds of individuals are admitted to the hospital, and tragically some do die from the flu.[10] (Level 5)

The prevention and treatment of influenza are best done with an interprofessional team that includes a nurse, nurse practitioner, primary care provider, internist, pharmacist, an emergency department physician, and an infectious disease specialist.

Each year, the flu affects millions of people and lead to time off work and school. The symptoms seriously affect the quality of life, and at extremes of age, the infection is known to cause death,

The key is patient education about vaccination. All patients should be encouraged to get the annual flu vaccine that is available in November of each year. Almost every school has a visiting nurse team that offers vaccination to students. In addition, pharmacists have now been given the authority to offer vaccinations to people who walk into the pharmacy. The key is to reduce the costs of healthcare as a result of people rushing to the emergency departments during winter. At the same time, patients are educated about hand washing, avoiding close contact until the symptoms subside, and drinking ample fluids. In addition, in most communities, there are surveillance programs run by epidemiologists to detect any epidemics. Only through such an interprofessional approach can the morbidity and mortality of the flu be lowered.

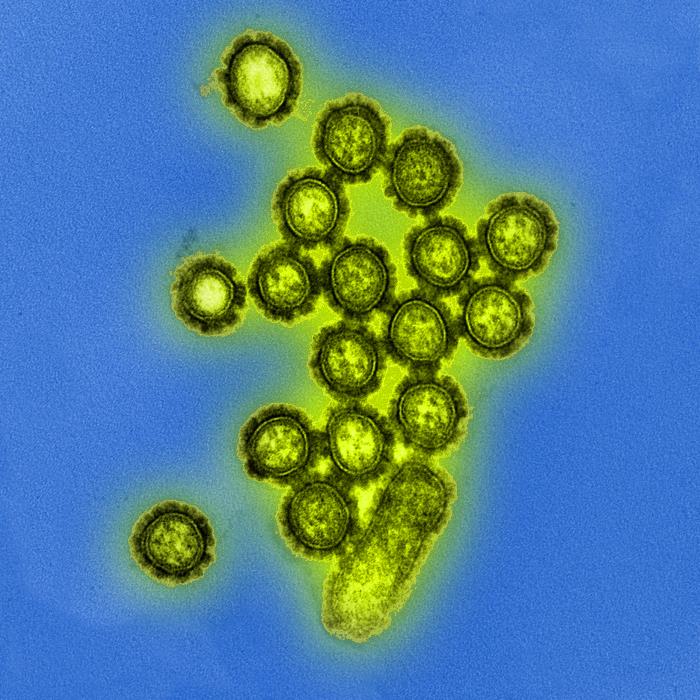

Electron Microscopic View of H1N1 Influenza Virus Particles. Digitally colorized transmission electron microscopic view of H1N1 influenza virus particles.

Public Health Image Library, Public Domain, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Alguacil-Ramos AM, Portero-Alonso A, Pastor-Villalba E, Muelas-Tirado J, Díez-Domingo J, Sanchis-Ferrer A, Lluch-Rodrigo JA. Rapid assessment of enhanced safety surveillance for influenza vaccine. Public health. 2019 Mar:168():137-141. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2018.12.013. Epub 2019 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 30769245]

Tennant RK, Holzer B, Love J, Tchilian E, White HN. Higher levels of B-cell mutation in the early germinal centres of an inefficient secondary antibody response to a variant influenza haemagglutinin. Immunology. 2019 May:157(1):86-91. doi: 10.1111/imm.13052. Epub 2019 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 30768794]

Marshall C, Williams K, Matchett E, Hobbs L. Sustained improvement in staff influenza vaccination rates over six years without a mandatory policy. Infection control and hospital epidemiology. 2019 Mar:40(3):389-390. doi: 10.1017/ice.2018.365. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30767814]

Odun-Ayo F, Odaibo G, Olaleye D. Influenza virus A (H1 and H3) and B co-circulation among patient presenting with acute respiratory tract infection in Ibadan, Nigeria. African health sciences. 2018 Dec:18(4):1134-1143. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v18i4.34. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30766579]

Havlickova M, Druelles S, Jirincova H, Limberkova R, Nagy A, Rasuli A, Kyncl J. Circulation of influenza A and B in the Czech Republic from 2000-2001 to 2015-2016. BMC infectious diseases. 2019 Feb 14:19(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3783-z. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30764763]

Yang L, Chan KP, Wong CM, Chiu SSS, Magalhaes RJS, Thach TQ, Peiris JSM, Clements ACA, Hu W. Comparison of influenza disease burden in older populations of Hong Kong and Brisbane: the impact of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination. BMC infectious diseases. 2019 Feb 14:19(1):162. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3735-7. Epub 2019 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 30764779]

Blanton L, Dugan VG, Abd Elal AI, Alabi N, Barnes J, Brammer L, Budd AP, Burns E, Cummings CN, Garg S, Garten R, Gubareva L, Kniss K, Kramer N, O'Halloran A, Reed C, Rolfes M, Sessions W, Taylor C, Xu X, Fry AM, Wentworth DE, Katz J, Jernigan D. Update: Influenza Activity - United States, September 30, 2018-February 2, 2019. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019 Feb 15:68(6):125-134. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806a1. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30763296]

Haber P, Moro PL, Ng C, Dores GM, Lewis P, Cano M. Post-licensure surveillance of trivalent adjuvanted influenza vaccine (aIIV3; Fluad), Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), United States, July 2016-June 2018. Vaccine. 2019 Mar 7:37(11):1516-1520. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.01.052. Epub 2019 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 30739795]

Kenmoe S, Tcharnenwa C, Monamele GC, Kengne CN, Ripa MN, Whitaker B, Alroy KA, Balajee SA, Njouom R. Comparison of FTD® respiratory pathogens 33 and a singleplex CDC assay for the detection of respiratory viruses: A study from Cameroon. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2019 Jul:94(3):236-242. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2019.01.007. Epub 2019 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 30738690]

Doyle JD, Chung JR, Kim SS, Gaglani M, Raiyani C, Zimmerman RK, Nowalk MP, Jackson ML, Jackson LA, Monto AS, Martin ET, Belongia EA, McLean HQ, Foust A, Sessions W, Berman L, Garten RJ, Barnes JR, Wentworth DE, Fry AM, Patel MM, Flannery B. Interim Estimates of 2018-19 Seasonal Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness - United States, February 2019. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019 Feb 15:68(6):135-139. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806a2. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30763298]