Learning Outcome

- Describe the presentation of chlamydia infection

- Recall the complications of chlamydia infection

- Summarize the treatment of chlamydia infection

- List the nursing care management of a patient with chlamydia

Chlamydia is a sexually transmitted infectious disease caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis. In the United States, it is the most commonly reported bacterial infection. Globally, it is the most common sexually transmitted diseases. It causes an ocular infection called "trachoma," which is the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide. In females, infertility and ectopic risks increase with Chlamydia trachomatis infections, leading to high medical costs.[1] Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), caused by distinct serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis, is a less common disease characterized by enlarged lymph nodes or severe proctocolitis.[2]

Chlamydia trachomatis is part of the chlamydophila genus. These bacteria are gram-negative, anaerobic, intracellular obligates that replicate within eukaryotic cells. C. trachomatis differentiates into 18 serovars (serologically variant strains) based on monoclonal antibody-based typing assays. These serovars correlate with multiple medical conditions as follows[3]:

Serovars A, B, Ba, and C: Trachoma is a serious eye disease endemic in Africa and Asia that is characterized by chronic conjunctivitis and can lead to blindness

Serovars D-K: Genital tract infections

Serovars L1-L3: Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), which correlates with genital ulcer disease in tropical countries

Urogenital chlamydia infections are the most commonly reported bacterial infections in the U.S and the most common cause of sexually transmitted disease in the world. The overall rate of urogenital infection amongst U.S. women is twice that among U.S. men, with a higher prevalence in women 15-24 years of age and a higher incidence in men between 20-24 years of age.

C. trachomatis can lead to many urogenital infections including cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, urethritis, epididymitis, prostatitis and lymphogranuloma venereum. Extragenital infections caused by C. trachomatis include conjunctivitis, perihepatitis, pharyngitis, reactive arthritis, and proctitis.

Most commonly, patients remain asymptomatic reservoirs of the disease. In the minority of patients that are symptomatic, clinical signs depend on the location of the infection. Below are the common signs and symptoms associated with C. trachomatis urogenital infections.

Among C. trachomatis infections, only trachoma is diagnosable on clinical grounds. Other chlamydial infections are associated with specific clinical syndromes but require laboratory confirmation. The gold standard for diagnosis of urogenital chlamydia infections is nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT). This test is run on either the vaginal swabs for women or first-catch urine for men. Testing can also be performed on endocervical or urethral swabs. Alternative methods of testing include culture, rapid testing, serology, antigen detection and genetic probes. If there is no testing available, treatment is recommended based on clinical presentation.

The goal of treatment is the prevention of complications associated with infection (e.g., PID, perihepatitis), to decrease the risk of transmission, and the resolution of symptoms. Treatment for uncomplicated urogenital chlamydia infection is with azithromycin. Doxycycline is an alternative, but azithromycin is preferred as it is a single-dose therapy.

Chlamydial infection and gonococcal infections often coexist. In men, the driver behind co-treatment for urogenital gonococcal infection should be by detection of the organism on NAAT or gram stain. In women, the gram stain is less helpful due to the possibility of normal Neisseria species colonization within the vaginal flora. Therefore, co-treatment should be dependent on an assessment of individual patient risk and local prevalence rates.

Patients should have partners identified and tested. They should also be counseled on high-risk behaviors, avoid sexual activity for one week after initiating therapy, and should consider testing for HIV.

Verification of cure should occur either three weeks after treatment completion, and retesting should be performed at three months after treatment.

If symptoms persist after treatment, consider coinfection with a secondary bacterium or reinfection.

In the United States and other developed countries, prevention of sexually transmitted genital infections and complications mainly focuses on screening and treating nonpregnant sexually active women aged 25 years or younger on an annual basis. Screening for pregnant women is recommended and screening and treatment of women over 25 years of age are recommendations if there are identifiable risk factors, such as new or multiple sexual partners. Screening of young men in high-risk settings (sexually transmitted disease and adolescent clinics, correctional facilities) should be a consideration if resources allow. Urine or endocervical NAAT are the recommended screening tests. The prognosis is excellent with prompt initiation of treatment early and with the completion of the entire course of antibiotics; antibiotic treatment is 95% effective for first-time therapy.

No vaccine is currently available for either trachoma or chlamydial genital infections.

The healthcare team including clinicians, nurses, and pharmacists must work together to educate the patient on methods to avoid exposure and the importance of completing treatment.

Asymptomatic infection with Chlamydia trachomatis is very common, whereas the consequences of undiagnosed or untreated infection can be far-reaching. It is for these reasons that screening is recommended. All pregnant women are recommended to be screened for C. trachomatis. All sexually active females younger than 25 should be screened annually. Women older than 25 should be screened if they have risk factors for sexually transmitted infections. Risk factors include sexual partners with multiple concurrent partners, new or multiple sexual partners, inconsistent use of condoms if the relationship is not monogamous, exchanging sex for money or drugs, or previous/coexisting STI. Men who have sex with men should also be screened for chlamydial infection. In individuals with HIV, screening should be done at the initial presentation and annually. For individuals entering a correctional facility, it is recommended to screen for chlamydia in women 35 years old or younger and men thirty years old or younger.

In the United States, C. trachomatis is considered a notifiable infection. Local and state laws regarding disease reporting apply. Sexual partners should be notified, examined, and treated if an STI is found in the index patient. Expedited partner therapy may also be available in certain settings. Expedited partner therapy allows providers to prescribe antibiotics to sexual contacts without establishing a physician-patient relationship.

Patients should be educated regarding the potentially serious consequences of chlamydia infections and the importance of screening. Patients also should be educated that screening can often be performed non-invasively with urine samples. Educated patients may then be agreeable to screening when they would otherwise hesitate out of fear of an uncomfortable exam.

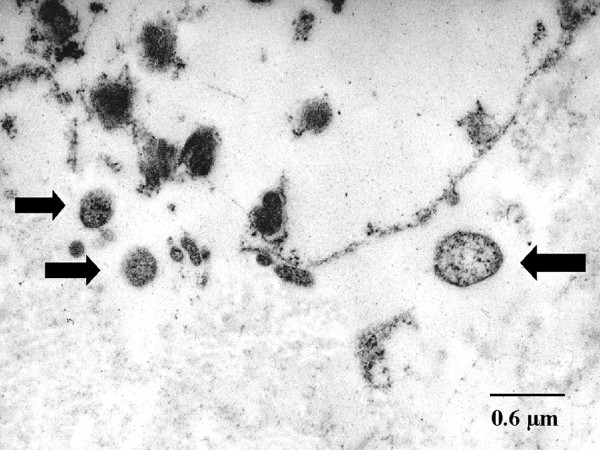

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency in Emphysema, Transmission Electron Microscopy. Chlamydial bodies are shown by arrows; also seen is the destruction of the interstitial connective tissue, with the ultrastructure less well preserved after the fixation of formaldehyde.

Theegarten D, Anhenn O, Hotzel H, et al. A comparative ultrastructural and molecular biological study on Chlamydia psittaci infection in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and non-alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency emphysema versus lung tissue of patients with hamartochondroma. BMC Infect Dis. 2004;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-4-38.

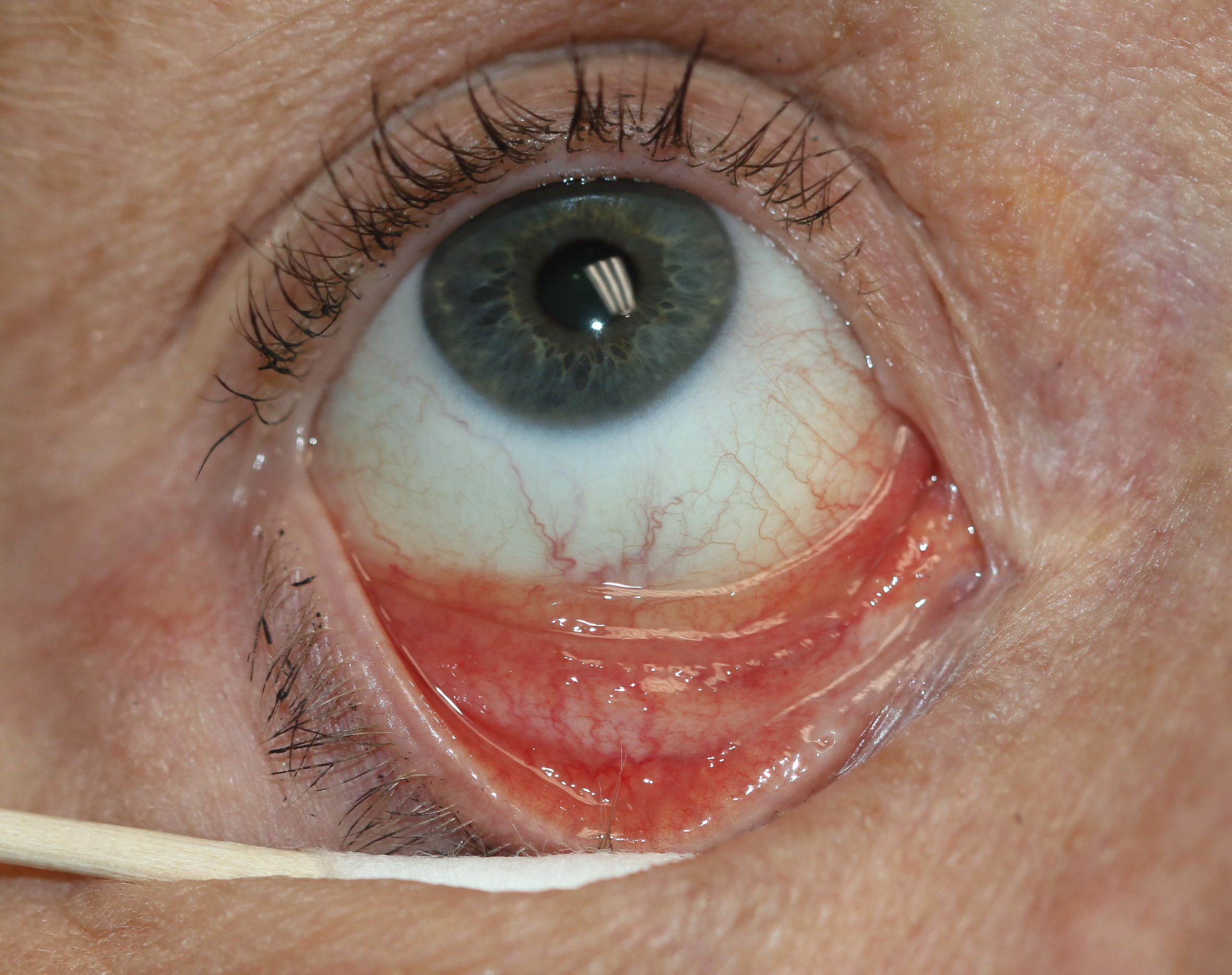

Follicular Conjunctivitis. Inflammation is noted with viral infections like herpes zoster, Epstein-Barr virus infection, infectious mononucleosis, and chlamydial infections, as well as in reaction to topical medications and molluscum contagiosum. Follicular conjunctivitis has been described in patients with COVID-19. The inferior and superior tarsal conjunctiva and the fornices show gray-white elevated swellings about 0.5 to 1 mm in diameter and have a velvety appearance.

Contributed by Prof. BCK Patel MD, FRCS

Owusu-Edusei K Jr, Chesson HW, Gift TL, Tao G, Mahajan R, Ocfemia MC, Kent CK. The estimated direct medical cost of selected sexually transmitted infections in the United States, 2008. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2013 Mar:40(3):197-201. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318285c6d2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23403600]

Mabey D, Peeling RW. Lymphogranuloma venereum. Sexually transmitted infections. 2002 Apr:78(2):90-2 [PubMed PMID: 12081191]

Morré SA, Rozendaal L, van Valkengoed IG, Boeke AJ, van Voorst Vader PC, Schirm J, de Blok S, van Den Hoek JA, van Doornum GJ, Meijer CJ, van Den Brule AJ. Urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis serovars in men and women with a symptomatic or asymptomatic infection: an association with clinical manifestations? Journal of clinical microbiology. 2000 Jun:38(6):2292-6 [PubMed PMID: 10834991]

Mordhorst CH, Dawson C. Sequelae of neonatal inclusion conjunctivitis and associated disease in parents. American journal of ophthalmology. 1971 Apr:71(4):861-7 [PubMed PMID: 4928532]

Detels R, Green AM, Klausner JD, Katzenstein D, Gaydos C, Handsfield H, Pequegnat W, Mayer K, Hartwell TD, Quinn TC. The incidence and correlates of symptomatic and asymptomatic Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections in selected populations in five countries. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2011 Jun:38(6):503-9 [PubMed PMID: 22256336]

. Pelvic inflammatory disease. American family physician. 2012 Apr 15:85(8):797-8 [PubMed PMID: 22534389]

Kobayashi S, Kida I. Reactive arthritis: recent advances and clinical manifestations. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2005 May:44(5):408-12 [PubMed PMID: 15942084]

Schachter J, Grossman M, Sweet RL, Holt J, Jordan C, Bishop E. Prospective study of perinatal transmission of Chlamydia trachomatis. JAMA. 1986 Jun 27:255(24):3374-7 [PubMed PMID: 3712696]

Tipple MA, Beem MO, Saxon EM. Clinical characteristics of the afebrile pneumonia associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection in infants less than 6 months of age. Pediatrics. 1979 Feb:63(2):192-7 [PubMed PMID: 440806]

Kohlhoff SA, Hammerschlag MR. Treatment of Chlamydial infections: 2014 update. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2015 Feb:16(2):205-12. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.999041. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25579069]

Workowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2015 Jun 5:64(RR-03):1-137 [PubMed PMID: 26042815]

Stamm WE, Batteiger BE, McCormack WM, Totten PA, Sternlicht A, Kivel NM, Rifalazil Study Group. A randomized, double-blind study comparing single-dose rifalazil with single-dose azithromycin for the empirical treatment of nongonococcal urethritis in men. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2007 Aug:34(8):545-52 [PubMed PMID: 17297383]

Rours GI, Duijts L, Moll HA, Arends LR, de Groot R, Jaddoe VW, Hofman A, Steegers EA, Mackenbach JP, Ott A, Willemse HF, van der Zwaan EA, Verkooijen RP, Verbrugh HA. Chlamydia trachomatis infection during pregnancy associated with preterm delivery: a population-based prospective cohort study. European journal of epidemiology. 2011 Jun:26(6):493-502. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9586-1. Epub 2011 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 21538042]

Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, Johnston CM, Muzny CA, Park I, Reno H, Zenilman JM, Bolan GA. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2021 Jul 23:70(4):1-187. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1. Epub 2021 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 34292926]

Bachmann LH, Barbee LA, Chan P, Reno H, Workowski KA, Hoover K, Mermin J, Mena L. CDC Clinical Guidelines on the Use of Doxycycline Postexposure Prophylaxis for Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevention, United States, 2024. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2024 Jun 6:73(2):1-8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7302a1. Epub 2024 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 38833414]