Learning Outcome

- Define atelectasis

- Identify risk factors for atelectasis

- Compare and contrast obstructive versus non-obstructive atelectasis

- Describe expected assessment and diagnostic findings in a patient experiencing atelectasis

- Select appropriate nursing interventions to support a patient experiencing atelectasis.

- Describe medical interventions that may be used for atelectasis

- Identify key patient education interventions

Introduction

The word "atelectasis" is Greek in origin; It is a combination of the Greek words atelez (ateles) and ektasiz (ektasis) meaning "imperfect" and "expansion". It results from the partial or complete, reversible collapse of the small airways leading to an impaired exchange of CO2 and O2. The incidence of atelectasis in patients undergoing general anesthesia is 90%.[1]

Nursing Diagnosis

- Impaired Gas Exchange and appropriate NANDA nursing diagnosis for atelectasis.

Causes

Atelectasis is one of three types: compressive, due to lung tissue compression, resorptive, caused by absorption of alveolar air, or related to an impairment of pulmonary surfactant production or function.[2]] It is categorized as either obstructive, non-obstructive, postoperative, and rounded atelectasis.

There are four types of nonobstructive atelectasis: compression, adhesive, cicatrization, relaxation, and replacement atelectasis. Compression atelectasis happens when there is increased pressure exerted on the lung which causes a transmural pressure difference between the extra and intra-alveolar space that results in alveolar collapse. During anesthesia, diaphragmatic relaxation occurs inhibiting the natural lowering of the diaphragm that occurs during spontaneous breathing. Lying in the supine position further displaces the diaphragm toward the head resulting in additional inhibition of gas exchange due to the further impairment of the transmural pressure gradient resulting in an increased risk of atelectasis. Adhesive atelectasis occurs due to either a surfactant deficiency or dysfunction. This type is commonly seen in patients with Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) or among premature infants with Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS). Surfactant prevents alveolar collapse by decreasing alveolar surface tension. Alterations to surfactant production and function tend to increase the surface tension within the alveoli lead creating instability resulting in collapse. Cicatrization atelectasis results in the contraction of the lung tissue to the development of parenchymal scar tissue. Cicatrization atelectasis is often seen in tuberculosis, fibrosis, and other chronic destructive lung diseases. Relaxation atelectasis occurs when there is a loss of contact between the parietal and visceral tissue. This happens with pneumothoraces and pleural effusions. Replacement atelectasis occurs when a tumor replaces the alveoli of an entire lobe of the lung, seen with bronchioalveolar carcinoma, resulting in the complete collapse of the lung.

In obstructive atelectasis, the air in the alveoli is absorbed distal to the point of obstruction. This is why it is referred to as resorptive atelectasis. In this instance, there is a mismatch between ventilation due to complete or partial obstruction of the alveoli and the uninterrupted perfusion of the alveoli. The presence of the ongoing ventilation-perfusion mismatch due to the obstruction results in the absorption of the gas in the alveoli precipitating the collapse. Obstructive atelectasis may be caused by intrathoracic tumors, mucous plugs, and foreign bodies. Children are at risk for resorption atelectasis due to aspiration foreign bodies because there are less developed collateral pathways for ventilation.

Adults with COPD are less likely to develop resorptive atelectasis related to an obstructive lesion due to better-developed collateral ventilation secondary to airway destruction. General anesthesia contributes to the development of absorptive atelectasis through the use of high inspiratory concentrations of oxygen ( FiO2). The risk for atelectasis due to the use of high FIO2 during anesthesia is related to the rates at which oxygen and nitrogen are absorbed into the bloodstream. Oxygen is rapidly absorbed, whereas nitrogen is not. Increasing the amount of oxygen inspired decreases the amount of nitrogen available to hold the alveoli open.

Postoperative atelectasis is normally seen within typically 72 hours of surgery using general anesthesia. Atelectasis is a known complication of general anesthesia.

Rounded atelectasis is rare. It is most often associated with asbestosis. It occurs because the lung tissue folds to the pleura.

Any of these mechanisms of atelectasis may contribute to perioperative atelectasis. Most frequently seen are the absorptive and compression variety.[3]

Middle lobe syndrome is the result of either an extraluminal or intraluminal obstruction of the bronchi which results in either a recurrent or fixed atelectasis of the lingula and right middle lobe of the lung. Inflammation, alterations in bronchial anatomy, and the presence of collateral ventilation are nonobstructive causes. Middle lobe syndrome is treated via bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage. Bronchiectasis may result from chronic atelectasis. Middle lobe syndrome has been associated with Sjorgen syndrome and treatment with steroids has shown promise.

Risk Factors

The incidence of atelectasis does not demonstrate gender differences. COPD, asthma, and increased age do not impact incidence either.[4] Atelectasis is more common in those who have recently had surgery using general anesthesia. Incidence has been reported as high as 90% in this group.[1] Research has demonstrated that the dependent portions of the lungs show indications of atelectasis within five minutes of beginning general anesthesia. [5] Atelectasis is more common following cardiac surgery with cardio-pulmonary bypass than any other surgery, including thoracotomy; however, the risk of atelectasis is higher in patients undergoing abdominal or thoracic surgery.[3] Obesity and pregnancy increase the risk for atelectasis due to upward displacement of the diaphragm (see the section on epidemiology).

Assessment

Typically, atelectasis is asymptomatic. However, a patient might also present with decreased or absent breath sounds, crackles, cough, sputum production, dyspnea, tachypnea, and/or diminished chest expansion.

Evaluation

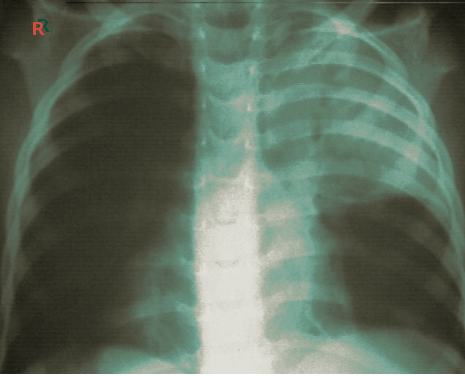

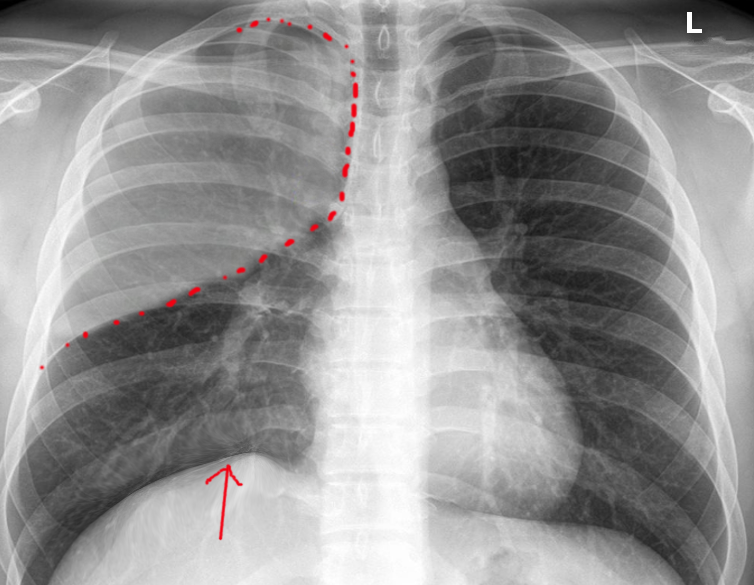

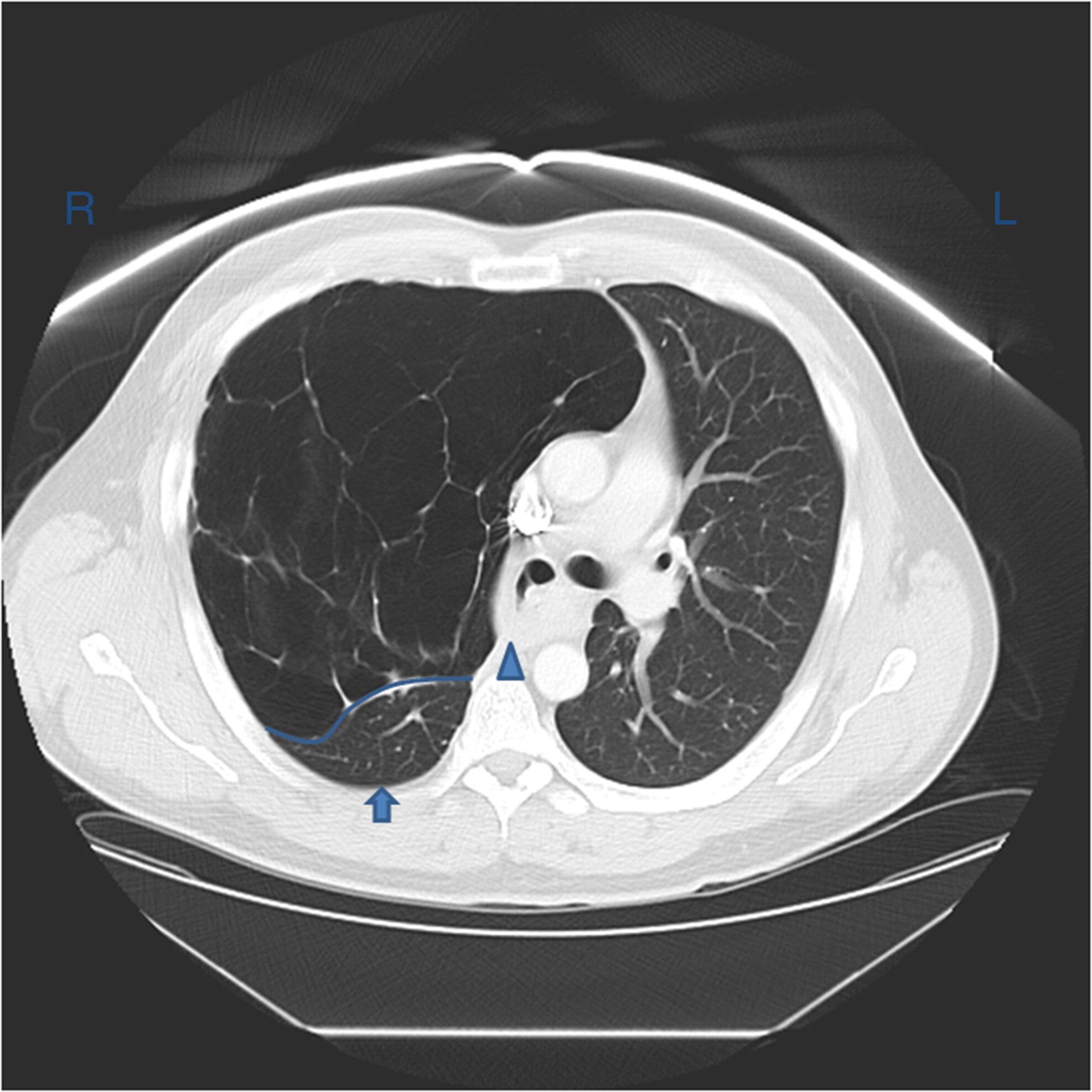

Atelectasis is usually clinically diagnosed in a patient with known risk factors. If an X-ray is warranted, a chest film, chest CAT scan (CT), and/or thoracic ultrasound may be useful to diagnose atelectasis. A chest x-ray will show platelike, horizontal lines in the area of atelectasis. Atelectasis is not usually seen on convention chest X-rays until it is significant.

On chest X-ray, the displacement of interlobar fissures, pulmonary opacification, and/or tracheal shift toward the affected side is seen with atelectasis.[6]

Chest CT shows densities in the dependent lung and decreased volume in the affected side.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy may allow direct visualization of atelectasis. It can be both diagnostic and therapeutic, as it may reveal the cause of an obstruction causing the atelectasis (i.e., tumor, mucous plug, or foreign body).

Arterial blood gas may demonstrate arterial hypoxemia and respiratory alkalosis with normal PaCO2. PaCO2 may be lower due to increased minute ventilation often seen in atelectasis.

Medical Management

A transient lung dysfunction leading to atelectasis caused by general anesthesia generally resolves itself within 24 hours. Unfortunately, some patients may develop significant respiratory complications resulting in increased morbidity and mortality without treatment. Prevention of atelectasis is achieved through the avoidance of general anesthesia, early mobility, adequate pain treatment including minimization of parenteral opioid use. When general anesthesia is required, steps should be taken to prevent the development of atelectasis such as: using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), using the lowest possible FiO2 during anesthesia administration, use of PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure), engaging in lung recruitment maneuvers, and using low tidal volumes.[7] One study demonstrated engaging in intraoperative alveolar recruitment followed by PEEP effectively prevented lung atelectasis in obese patients resulting in better oxygenation, shorter recovery room time, and fewer pulmonary complications postoperatively.[8]

Sitting upright increases functional residual capacity (FRC) decreasing atelectasis.[9] Other interventions that have been used to decrease atelectasis include deep breathing; early ambulation; proper use of an incentive spirometer or acapella device; chest physiotherapy; tracheal suctioning if intubated; and use of positive pressure ventilation. Each of these interventions temporarily increases the transmural pressure gradient resulting in the re-expansion of collapsed areas of the lung. Preoperatively patients should be taught atelectasis prevention measures, such as incentive spirometry. In the case of incentive spirometry, it is believed that this intervention should begin preoperatively and then continue postoperatively with hourly use encouraged to achieve maximal benefit.

Mucolytic agents (acetylcysteine) and recombinant human DNase (dornase alpha) are pharmacologic agents which may be of some benefit in patients with cystic fibrosis, as mucous plugs are often seen in this patient population.

Bronchoscopy may be used to manage atelectasis. In one study, bronchoscopy resulted in improved lung function reversing atelectasis 76% of the time. Bronchoscopy should be used when mechanical obstruction of the bronchus is suspected and coughing or suctioning has not been successful. Bronchoscopy should also be considered when early ambulation, incentive spirometry, bronchodilators, and humidity, have not been successful after 24 hours of use.

Engaging in preventative strategies early and promptly recognizing atelectasis will improve patient outcomes and significantly decrease cost.[10]

Nursing Management

Patients enter the hospital environment with a variety of risk factors that place them at risk for the development of atelectasis. Among these risk factors is a history of cardiovascular disease, pulmonary disease, particularly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neuromuscular disease, kidney failure, cancer, and autoimmune disorders. In addition, tobacco use, obesity, traumatic injury, advanced age, and recent respiratory illness are also risks.[10] Careful assessment of the patient's respiratory status is required throughout the hospitalization. Particular attention should be given to lung sounds for diminishment and /or crackles. Complaints of dyspnea should be reported. The presence of cough should be further assessed for sputum production. Characteristics of sputum should be reported to the physician. Vital signs should be monitored for tachypnea. Fever may occur, but this is not necessarily attributable to atelectasis.[10]

Incentive spirometry has been a mainstay of nursing postoperative atelectasis prevention. Recent studies have indicated that incentive spirometry alone may not be sufficient to prevent untoward outcomes in postoperative patients. Evidence indicates that the use of deep breathing, adequate pain relief, directed cough, and early patient mobilization are also necessary to increase lung volumes [11].

When To Seek Help

Dyspnea, tachypnea, and increased work of breathing as exhibited by the use of accessory muscles during respirations should be reported to the physician. Changes in the character of lung sounds, cough, and sputum production should also be reported.[10]

Coordination of Care

Preventing atelectasis is vital to improving the outcomes of the postoperative patient. Unfortunately, atelectasis may not always be prevented. Therefore, early recognition and treatment are also important, as this can decrease the length of hospitalization, cost, and improve patient outcomes.

Prevention and treatment of atelectasis require an interprofessional team effort. Physicians, particularly surgeons and anesthesiologists, must consider the role of anesthesia in atelectasis. Nursing needs to monitor the patient pre and post-procedure. Pharmacists can provide regarding the use of opioids and mucolytics. The nurses administering these medications should report on the efficacy of therapy as well as any adverse events, resulting in dose or medication changes, or other interventions. Nursing should help to educate the patient and family regarding interventions to minimize the risk of atelectasis, such as incentive spirometry. incentive spirometry. In summary, atelectasis management takes a collaborative interprofessional team to optimize patient outcomes. [Level V]

Health Teaching and Health Promotion

Atelectasis is a partial collapse of the lung which causes shortness of breath. It may be the result of several different processes, most often associated with poor inspiratory effort, airway obstruction blocking air movement into the lung, additional pressure placed on the outside of the lung, or alterations in the production or function of a protein called surfactant in the lung. Treatment addresses underlying causes of the condition but consists most often of supportive measures, such as deep breathing, incentive spirometry, and providing supplemental O2.

Discharge Planning

In the past, it was believed that postoperative fever was caused by atelectasis. There is no evidence to support this belief.[12]