Continuing Education Activity

The atrioventricular septal defect is a congenital cardiac malformation that is characterized by a variable degree of the atrial and ventricular septal defect along with a common or partially separate atrioventricular orifice. Diagnosis of AVSD in fetal life or early neonatal period is essential in order to initiate appropriate medical treatment and to plan early surgical repair. In order to avoid the high morbidity and mortality associated with this condition, it must be promptly diagnosed and treated. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of AVSD and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Identify the etiology of atrioventricular septal defects.

- Outline the evaluation of atrioventricular septal defects.

- Review the management options available for atrioventricular septal defects.

Introduction

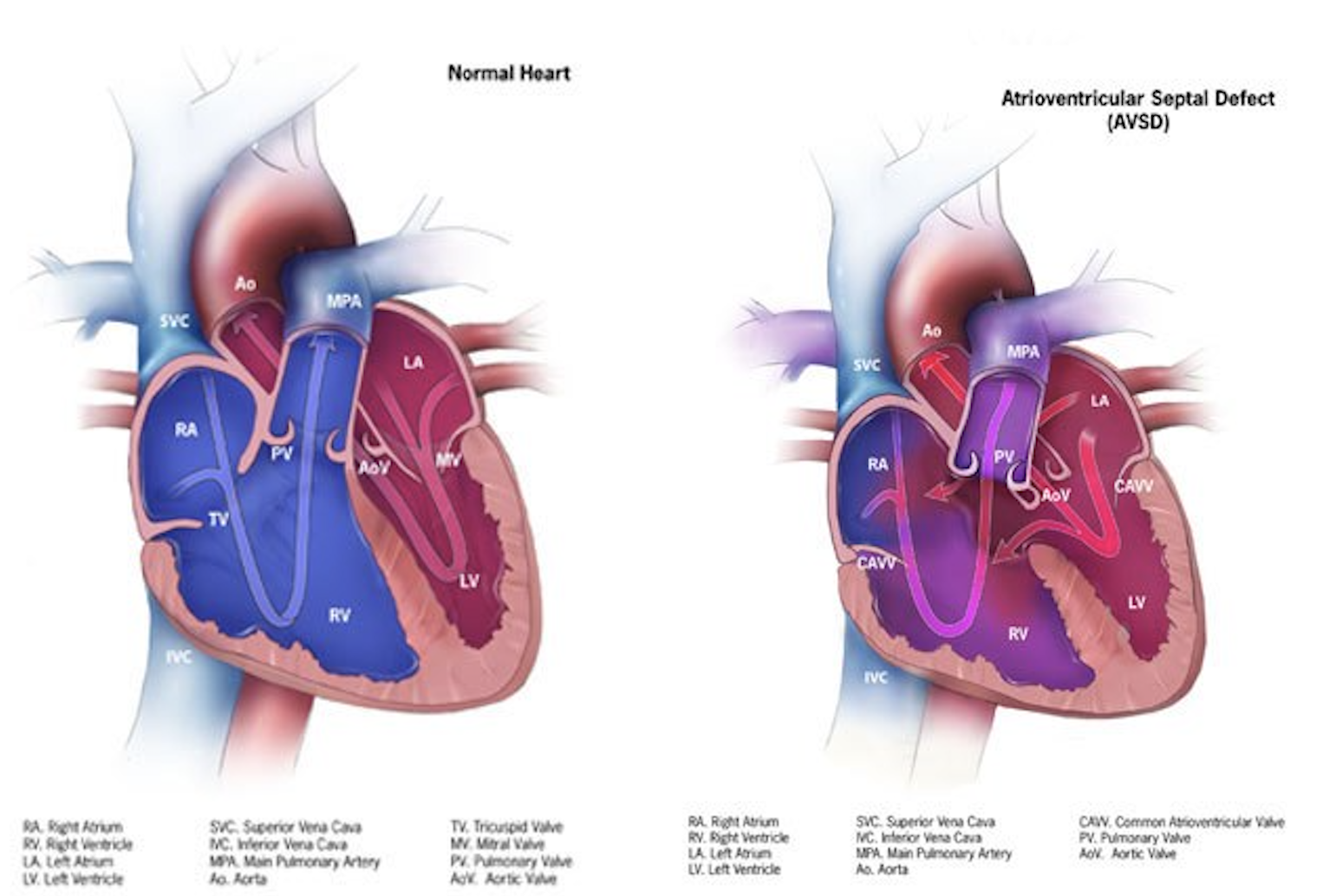

The atrioventricular septal defect is a congenital cardiac malformation that is characterized by a variable degree of the atrial and ventricular septal defect along with a common or partially separate atrioventricular orifice.[1] A partial atrioventricular septal defect is characterized by an ostium primum atrial septal defect, separate atrioventricular valves with a common junction, an inlet ventricular septal defect, and a cleft mitral valve. Whereas the complete form of the atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) is characterized by a common atrioventricular valve with ostium primum atrial septal defect and an unrestricted ventricular septal defect of inlet type.[2]

The incidence of atrioventricular septal defect has been estimated from 0.24 to 0.31 in 1000 live births with no significant difference in male and female gender, and it has a strong association with Down’s syndrome.[3] Although the long term outcomes of surgical repair in an atrioventricular septal defect are influenced by the presence of associated malformations, such as ventricular hypoplasia, and down`s syndrome, the evolution of the surgical treatment of atrioventricular defects over the last few decades has significantly improved the long term survival. In this review article, we will discuss the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, as well as management, complications, and clinical significance of atrioventricular septal defect.

Etiology

In almost all patients, the atrioventricular septal defect is caused by genetic mutations, and most of the time, it is associated with syndromes. Every six patients with Down syndrome have associated atrioventricular septal defect, and Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (DSCAM) gene has been described to be associated with an atrioventricular septal defect and other congenital heart diseases in these patients.[4][5]

The other syndromes associated with the atrioventricular septal defect may include CHARGE, Ellis-van-Creveld, Smith-Lemli-Opitz, and 3p. Other than its association with syndromes, gene mutations associated with the atrioventricular septal defect can also be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Gestational diabetes and maternal obesity have also been reported to increase the risk of non-syndromic atrioventricular septal defects.[6]

Epidemiology

The incidence of an atrioventricular septal defect in the general population has been reported to be 0.24 to 0.31 per 1000 live births.[3] It accounts for 3% of all congenital cardiac malformations.[2] Although both male and female genders are affected equally, one of the studies suggests a female to male ratio of 1.3 to 1.0, especially in patients with Down syndrome.[7]

Pathophysiology

Endocardial cushions are paired (superior and inferior) mesenchymal structures located in the common atrioventricular canal in the early embryonic period, and there growth is of prime importance in the development of atrioventricular septum and atrioventricular valves.[8] These endocardial cushions fuse at the end of 4 weeks of development and form two atria and two ventricles. Failure of fusion results in a variable degree of the atrioventricular septal defect.

Based on atrioventricular valve morphology and its development, atrioventricular septal defects are classified into complete and partial.

A complete atrioventricular septal defect is characterized by a common atrioventricular valve, ostium primum atrial septal defect and ventricular septal defect of inlet type. It is caused by the complete failure of the endocardial cushions to fuse.[9]

A partial atrioventricular septal defect is characterized by separate atrioventricular valves, an ostium primum atrial septal defect, a ventricular septal defect of inlet type, and cleft mitral valve. It is caused by incomplete fusion of endocardial cushions.[10]

In the complete form of the atrioventricular septal defect, a common atrioventricular valve has five leaflets, including superior bridging, interior bridging, left mural, right mural, and anterosuperior. Rastelli divided complete atrioventricular septal defect into three anatomical subgroups.[11]

In type A, the superior bridging leaflet of the common atrioventricular valve is attached to the left ventricular surface of the interventricular septum with the help of chordae.

In type B, the superior bridging leaflet of common atrioventricular valve overhangs the interventricular septum and attached to the right ventricle with the help of chordae.

In type C, the superior bridging leaflet does not have an attachment to the interventricular septum and floats freely, thus provides a large unrestricted ventricular septal defect.

Rastelli type A is associated with left-sided obstruction, type C is associated with tetralogy of Fallot and other complex congenital heart diseases, and type B is the least common form of the complete atrioventricular septal defect.

History and Physical

Clinical presentation of atrioventricular septal defects is influenced by the type of atrioventricular septal defect, the magnitude of the intracardiac shunt, and other associated cardiac malformations.[3] In patients with complete atrioventricular septal defect, signs of pulmonary congestion, and right heart failure develop in early infancy due to significant left to right shunt as pulmonary vascular resistance drops after birth. Heart failure and Eisenminger may develop even earlier if these patients have associated atrioventricular valve regurgitation, ventricular imbalance, or coarctation of the aorta.[12]

Patients with the partial atrioventricular septal defect without other complex congenital cardiac malformations and minimal atrioventricular valve regurgitation, usually remain asymptomatic in infancy and early childhood. They are diagnosed on the bases of incidental findings, including pulmonary or tricuspid flow murmur and a fixed splitting due to atrial septal defect.

Symptoms of heart failure in infants may include difficulty in feeding, sleepiness, lethargy, and failure to thrive, while children may have a complaint of dyspnea.

Signs of heart failure include:

- Tachypnea, tachycardia

- S3 gallop

- Rales on chest auscultation

- Raised jugular venous pressure

- Tender hepatomegaly

- Wide fixed splitting due to atrial septal defect

- Pansystolic murmur due to atrioventricular valve regurgitation

- Pulmonary flow murmur due to increased flow through the pulmonary valve

- Mid diastolic flow murmur due to increased flow through the tricuspid valve

General physical examination may reveal cyanosis when there is a reversal of shunt (Eisenmenger syndrome) and dysmorphic features in case of associated syndromes.

Evaluation

Antenatal Evaluation

Antenatal ultrasonography with a four-chamber view is the commonly used diagnostic test for the atrioventricular septal defect. The most common findings include a common atrioventricular valve and a defect in the atrial or ventricular septum. However, the sensitivity of antenatal ultrasound for the atrioventricular septal defect is very low.[13]

Postnatal Evaluation

Chest Radiograph: It demonstrates cardiomegaly and pulmonary plethora, especially in those cases with associated atrioventricular valve regurgitation.

Electrocardiogram: The characteristic electrocardiographic findings include a superior axis in the frontal plan, right ventricular hypertrophy, and atrioventricular block. Other findings may include superior p wave axis and partial right bundle branch block.

Echocardiogram: Echocardiographic findings include:[14]

- Abnormal configuration of atrioventricular valve

- Loss of normal offset of atrioventricular valve

- Abnormal position of papillary muscles

- Disproportion in left ventricular inlet and outlet

- Ostium primum atrial septal defect

- Ventricular septal defect of inlet type

- And other associated cardiac malformations.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Magnetic resonance imaging reveals findings similar to an echocardiogram. It is more accurate in measuring the size of defects and regurgitation fraction through the atrioventricular valve.

Treatment / Management

The management of atrioventricular septal defects can be divided into medical and surgical treatment.[15]

Medical Treatment

It includes diuretics and vasodilators to reduce the preload and afterload to relieve the symptoms associated with pulmonary congestion and heart failure. Associated feeding problems and failure to thrive are managed by tube feeding and providing extra calories. In atrioventricular septal defects, medical treatment is usually directed at optimizing the condition of the patient for surgery.[3]

Surgical Treatment

Surgical correction is the ultimate treatment of atrioventricular septal defect. Atrioventricular septal repair is a complex surgical procedure and carries operative mortality of more than 3% even in the contemporary era of advanced surgical techniques.[16] It also carries significant postoperative mortality and morbidity due to residual intracardiac shunts, atrioventricular valve regurgitation, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, and arrhythmias.[17]

Assessment of pre-operative imaging and hemodynamic data is essential for the optimal selection of surgical procedures to reduce the requirement of recurrent surgery and postoperative complications.[18] In previous studies, the requirement of the recurrent procedure is reported as high as 18.2% at 15 years after surgical correction and left atrioventricular valve dysplasia, absence of cleft closure and associated cardiac malformations are found to increase the rate of recurrent procedures.[19]

In complete AVSD, surgical closure should be performed in early infancy to reduce the pulmonary vascular disease, whereas, in incomplete atrioventricular septal defect, a repair can be slightly delayed if the patient is not symptomatic.

For partial AVSD, the primary repair is preferred with patch closure and atrioventricular valvuloplasty.

For balanced complete AVSD, early primary repair with two patch closure techniques is preferred over one patch closure, as one patch closure is associated with an increased rate of recurrent procedures due to patch dehiscence and residual shunt. Pulmonary artery banding is no longer used as a routine procedure in complete AVSD repair.[20]

For unbalanced complete AVSD, repair technique may include single ventricle palliation with the staged biventricular repair or primary biventricular repair.[17]

Differential Diagnosis

Common differential diagnoses of AVSD include ostium secondum atrial septal defect, isolated ventricular septal defect and tetralogy of Fallot. The symptoms of heart failure and enlargement of cardiac chambers are common in these malformations, and echocardiogram plays a major role in differentiating AVSD from the aforementioned conditions.

Prognosis

The prognosis of untreated atrioventricular septal defect is dismal. Around 50% of the patients die during infancy, either due to heart failure or pulmonary infections.[2] Those who survive beyond one year, they develop the irreversible pulmonary vascular disease and later on the reversal of the shunt.

Patients undergoing surgical repair have 15 years of survival of around 90%, and 9% to 10% of those require reoperation within 15 years.[21]

Complications

Most of the complications of AVSD are related to intracardiac shunts or atrioventricular valve regurgitation. In complete AVSD, shunting of blood from left to right leads to right-sided overload and signs of heart failure and pulmonary congestion at a very early age, which contributes to significant mortality during infancy. If the shunt is not corrected, it causes an irreversible pulmonary vascular disease that leads to pulmonary hypertension and Eisenmenger syndrome.

Regurgitation of blood from the ventricle to atria through the atrioventricular valve leads to pulmonary congestion and enlargement of the atrium. Enlargement of the atrium can lead to supraventricular arrhythmias. Other complications are related to poor feeding, which may include malnutrition and failure to thrive.

Deterrence and Patient Education

How can an atrioventricular septal defect be diagnosed?

It is usually diagnosed by a cardiologist (who is a specialist in congenital cardiac diseases). He makes the diagnosis based on symptoms of heart failure and examination findings, including a murmur. Then he may advise a few tests to confirm the diagnosis. These tests may include:

- Chest radiograph: It is used to take a picture of the lungs and heart.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): It detects any abnormality in the electrical activity of the heart.

- Echocardiogram: It uses sound waves and creates a picture of the internal structure and parts of the heart.

- Cardiac catheterization: It measures blood pressure and concentration of oxygen inside the heart chambers and helps the doctor detect Intracardiac shunting of blood.

How can an atrioventricular septal defect be treated?

It is treated by surgically repairing the defect in the first year of life. Sometimes medications are given by the doctor to reduce the symptoms of heart failure.

These medications may include pills to excrete extra water from the body via urine (diuretics) and pills, which dilate the blood vessels and decrease the peripheral vascular resistance.

Pearls and Other Issues

Diagnosis of AVSD in fetal life or early neonatal period is essential in order to initiate appropriate medical treatment and to plan early surgical repair. In the contemporary era of advanced surgical techniques, the operative mortality of atrioventricular septal defect repair is low with excellent long term outcomes even in patients with Down syndrome.

Atrioventricular valve regurgitation is the most common reason for reoperation, that’s why it is mandatory to assess the imaging data before surgical repair and pay detailed attention to atrioventricular valve repair at the time of primary repair. Postoperatively patients should be followed regularly for atrioventricular valve regurgitation and left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.[3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An atrioventricular septal defect is a complex congenital cardiac malformation, which requires a multidisciplinary and interprofessional approach in order to optimize medical treatment, decrease surgical mortality, and improve long term outcomes. A multidisciplinary team is the cornerstone of a multi-professional approach, which may include a pediatric cardiologist, a cardiac imaging expert, a pediatric cardiac surgeon, a cardiac anesthesiologist, a cardiac nurse, a nutritionist, and a cardiac pharmacist.

During fetal life and early infancy, a detailed screening for congenital cardiac malformations is mandatory in order to make an early diagnosis of the atrioventricular septal defect. After an early diagnosis, it is essential to institute appropriate medical therapy and plan surgical repair. Assessment of imaging and hemodynamic data is essential for planning a surgical repair.

In the postoperative period, wound care, appropriate nutrition, and nursing care are important to reduce the duration of hospitalization and promote early postoperative recovery. Meticulous postoperative follow up is required to monitor and assess the long-term complications of surgical repair and the need for recurrent surgery.