Introduction

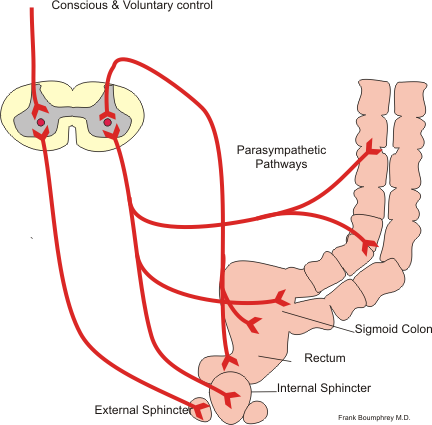

Defecation is the term for the act of expelling feces from the digestive tract via the anus. This complex function requires coordination between the gastrointestinal, nervous, and musculoskeletal systems.[1] The process begins with mass movement from the colon to the rectum, initiating the defecation reflex, which involves rectal contraction and internal and external anal sphincter relaxation. Defecation is involuntary from the colon to the internal anal sphincter, where smooth muscles push feces out. However, it is under conscious or subconscious control at the level of the external anal sphincter, which is lined by striated muscles (see Image. Defecation Reflex).

This article focuses on the physiologic process driving defecation.

Cellular Level

Columnar epithelium lines the rectum, which becomes stratified squamous epithelium at the recto-anal junction or the transitional zone just superior to the dentate line. Two sphincters control defecation. The internal anal sphincter consists of smooth muscle cells and is under involuntary control. The external anal sphincter consists of skeletal muscle tissue and is under voluntary control.[2]

Development

Defecation is an involuntary process during infancy. Toilet training helps children learn to control the urge to defecate and only do so when it is socially acceptable. How soon this skill is acquired depends on the age when toilet training began and the training method used.[3]

Organ Systems Involved

Fecal movement from the colon to the rectum induces the urge to defecate. The Valsalva maneuver and abdominal muscle contractions increase intraabdominal pressure to expel feces faster. The external anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle relax to let feces pass out of the rectum. The levator ani and puborectalis muscles work together to allow complete fecal expulsion.[1]

Rectal afferent nerves are responsible for the sensation of rectal fullness and the urge to defecate. Direct branches from S2 to S4 and the pudendal nerve supply the voluntary muscles involved in defecation.[4]

Function

Feces are composed of 75% water and 25% solid material. Fecal solid components include the following:

- Undigested food components like cellulose - 30%

- Bacteria - 30%

- Inorganic substances such as iron phosphate and calcium phosphate - 10-20%

- Cholesterol and other fats - 10-20%

- Protein - 2-3%

Gastrointestinal mucous membranes also shed cell debris, which passes into the waste material. Bile pigments and leukocytes are also found in feces. Stercobilin colors the feces brown. This substance is the product of the bacterial metabolism of bilirubin. Fecal odor is caused by chemicals such as hydrogen sulfide, skatole, indole, and mercaptans.[5]

Mechanism

Colonic mass movements and peristalsis move intestinal contents distally into the rectum. Rectal distention stimulates stretch receptors, with the signals spreading to the descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum via the myenteric plexus. The process initiates the defecation reflex and forces feces toward the anus.

Inhibitory myenteric plexus signals relax the internal anal sphincter as the peristaltic waves approach the anus. Defecation occurs when the external anal sphincter is voluntarily relaxed.

The myenteric defecation reflex is weak on its own. However, parasympathetic impulses bolster the myenteric signals. Craniosacral involvement starts with rectal wall distention sending afferent signals via the pelvic nerve to the defecation center in the spinal cord. The spinal defecation center sends back motor impulses to the descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum via pelvic nerve efferents. Parasympathetic signals cause strong sigmoid and rectal contractions and internal anal sphincter relaxation.

Spinal cord signals initiate other actions, particularly glottis closure, abdominal wall contraction, and pelvic floor relaxation. One can purposely activate the defecation reflex by taking a deep breath and contracting the abdominal muscles to increase abdominal pressure. Together, these actions force fecal content into the rectum to cause new reflexes. However, voluntary initiation of the defecation reflex is never as effective as when it starts involuntarily. On the other hand, suppressing the involuntary parts of defecation can lead to constipation.

People can prevent defecation by voluntarily tightening the external anal sphincter. If defecation is delayed long enough, the rectal wall relaxes, and the urge to defecate subsides until another mass movement distends the rectum and stimulates the reflex again.

The gastrocolic and duodenocolic reflexes facilitate mass movements after meals. These reflexes are physiologic responses produced when postmeal stomach and small bowel distention induce colonic peristalsis and fecal movement.[6] Colonic irritation, eg, from inflammation and infection, can also initiate mass movements, which persist until the insult is eliminated.[7]

Related Testing

Manometry can help assess colonic and anal sphincter contractility. The test is useful in identifying the cause of constipation or fecal incontinence.[8] Colonic transit time examination determines the speed at which stool moves through the colon. This test is performed by asking the patient to swallow a marker-filled capsule. Serial abdominal X-rays are taken until the marker capsule is completely expelled.

Stool analysis identifies fecal content abnormalities such as high bacterial, erythrocyte, or leukocyte count and the presence of parasites.[9] A flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may be necessary to confirm the presence of colonic or rectal lesions if the fecal composition is deranged.[10]

Pathophysiology

Disorders of defecation can be classified into 3 categories, namely, diarrhea, constipation, and fecal incontinence. The possible causes and pathophysiology of these conditions are explained below.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is an increase in stool frequency, liquidity, or volume.[11] This condition is further subcategorized into the following types:

- Secretory

- Osmotic

- Inflammatory

- Functional

Secretory diarrhea is caused either by decreased absorption or increased secretion of electrolytes and water by the intestinal epithelium. Vibrio cholerae produces secretory diarrhea. Malignancies like VIPoma and carcinoid tumors may also cause this condition.[11] Medications like zidovudine and irinotecan can likewise increase intestinal fluid secretion.[12]

Osmotic diarrhea occurs when a solute draws water into the colonic lumen, causing fluid to accumulate within. Examples of such solutes are lactose and gluten. Hence, this type of diarrhea is common in malabsorption syndromes like lactose intolerance and celiac disease. Osmotic diarrhea can also result from the ingestion of osmotically active substances such as magnesium and sulfate, which are common laxative ingredients.[11]

The fecal osmotic gap helps distinguish secretory from osmotic diarrhea. The equation is:

Fecal osmotic gap = 290 – 2 * (stool sodium + stool potassium)

An osmotic gap greater than 125 mOsm/kg is characteristic of osmotic diarrhea. Meanwhile, an osmotic gap less than 50 mOsm/kg is more indicative of the secretory type.[13] Osmotic diarrhea can improve with fasting, which reduces osmotic load. By comparison, fasting is ineffective in secretory diarrhea.[13]

Inflammatory diarrhea occurs when the bowel epithelium is inflamed, as in conditions like Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, and invasive infections from Clostridium difficile or Shigella.[14] The stool often contains blood, white blood cells, and mucus.[11]

Functional diarrhea is a diagnosis of exclusion. The exact etiology is unknown, but gut microbiome alterations and rapid intestinal transit time of fecal matter are implicated.[15] The most common form of functional diarrhea is irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The Rome criteria are used for diagnosing IBS.[16]

Constipation

Constipation is reduced defecation frequency, generally 3 or fewer per week. Stool hardening occurs, forcing individuals to strain when attempting defecation.[17] Constipation can be a side effect of medications that reduce gastric motility, such as anticholinergic and narcotic agents. Other causes of this condition include a low-fiber diet, disorders of the nerves and muscles involved in defecation, and prolonged suppression of the defecation urge.[17]

Obstipation is the term used for severe constipation. Feces are so dry and impacted that defecation becomes extremely difficult. Obstipation almost always requires medical or surgical intervention.

Fecal Incontinence

Fecal incontinence is the inability to control the passage of stool. This condition occurs most frequently in older individuals, though it may also arise as a complication of labor and anorectal surgery in younger patients. Congenital causes include spinal cord defects and anorectal malformation.[18]

Clinical Significance

Defecation pattern changes may be a sign of illness or a side effect of therapy. A complete workup must be initiated if changes in bowel movement are accompanied by alarming symptoms like rectal bleeding, weight loss, anemia, a palpable abdominal mass, and fatigue.[19]

Constipation is a common clinical complaint with a multitude of causes. Mild cases may be treated by increasing dietary fiber and taking laxatives. Impacted stools may require suppositories, enemas, or manual disimpaction.

Dyschezia is a condition characterized by severe pain on defecation despite having a normal defecation reflex. A number of conditions may cause dyschezia, ranging from benign conditions like hemorrhoids to inflammation and malignancy.

Tenesmus is the frequent urge to defecate even if the bowels are empty. This condition presents with involuntary straining, severe abdominal cramping, and discomfort.