Continuing Education Activity

This activity outlines the transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks, relevant anatomy, indications, and contraindications to performing this block. It will also highlight several techniques and approaches to performing TAP blocks and the importance of an interprofessional team in conducting the procedure.

Objectives:

Identify several techniques to approach transversus abdominis plane blocks.

Evaluate patients who would benefit from transversus abdominis plane blocks.

Assess relevant anatomy associated with transversus abdominis plane blocks.

Communicate the importance of an interprofessional team approach when delivering transversus abdominis plane blocks to a patient.

Introduction

A rise in opioid-related adverse effects and death has led to a surge in utilizing alternative methods to treat pain. The increasing adoption of ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia for acute pain management parallels the rapid availability of ultrasound machines. The abdominal wall is a common source of pain after surgical interventions involving the abdomen. Utilizing ultrasound, transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks can provide reliable relief of somatic incisional pain. TAP blocks are a great adjunct to a multimodal analgesic regimen. However, the lack of reliable visceral pain relief with TAP blocks may necessitate additional modes of analgesia.[1][2] The TAP is a potential anatomical space between transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles, where local anesthetic can be deposited, creating a non-dermatomal “field block.”[3]

Anatomy and Physiology

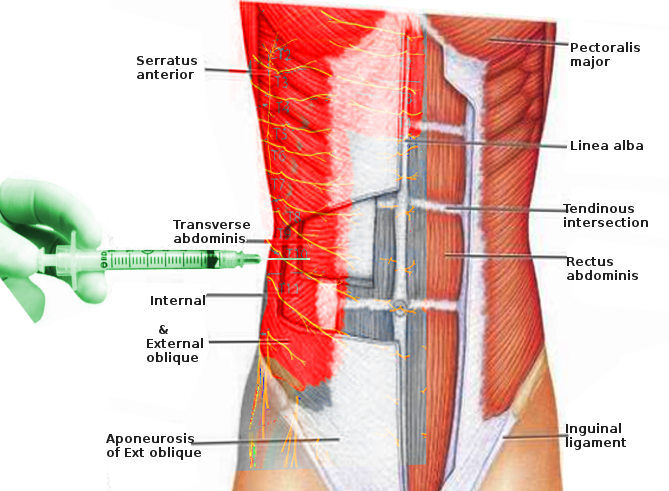

The anterolateral abdominal wall is bound laterally by the posterior axillary lines, superiorly by the costal margin of the 7th to 10th ribs and xiphoid process, and inferiorly by the iliac crest, inguinal ligament, pubic crest, and symphysis. The anterolateral abdominal wall muscles, from superficial to deep, include the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. The TAP is the fascial plane that separates the transversus abdominis muscle from the internal oblique muscle. The anterolateral abdominal wall is innervated and composed of the thoracoabdominal ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves, which communicate to form the upper and lower TAP plexuses. Therefore, to achieve complete anesthesia of the abdominal wall, several injections must be made to cover the nerves of T6-L1.[4] The intercostal nerves of T6-T9 can be anesthetized subcostally as they only enter the TAP medial to the anterior axillary line, T6 entering just lateral to the linea alba. T10-T12 nerves enter more laterally and can be blocked in the midaxillary line between the bottom of the thoracic cage and the top of the iliac crest.

Each TAP block generally provides analgesia to 1 quadrant of the abdominal wall. To block the L1 segment, an injection medial to the anterior superior iliac spine must be performed. A major limitation of the TAP block is that while it provides somatic analgesia, it fails to provide analgesia for visceral pain.[2] The transversus abdominis muscle and the internal oblique muscle taper off posteriorly into their origin as the thoracolumbar fascia. This fascia surrounds the quadratus lumborum and erector spinae muscles. The external oblique muscle ends posteriorly, neighboring the latissimus dorsi muscle. The 3 muscles (external, internal, and transversus abdominis muscles) converge medially, and their aponeurosis forms the rectus sheath. The transversalis fascia is a thin aponeurotic membrane between the transversus abdominis muscle and the parietal peritoneum.

Indications

Common indications for TAP blocks include:

- Major abdominal surgery

- Colorectal surgeries

- Hernia repairs

- Procedures involving the abdominal wall

- Cesarean section

Contraindications

Contraindications to TAP blocks include the following:

- Patient refusal

- Active infection over the site of injection

- Practice caution in patients taking anticoagulation, pregnant patients, and patients where anatomical landmarks are indistinguishable

- Avoid local anesthetics in those with known allergies

Equipment

Materials for ultrasound-guided TAP blocks include the following:

- 27- to 30-gauge 1.5-inch needle

- A 20-mL syringe

- A 5-ml syringe

- Sterile gloves

- Sterile towels

- Anesthetic agent: ropivacaine or bupivacaine without epinephrine, liposomal bupivacaine

- Local anesthetics for skin infiltration, such as 1% lidocaine without epinephrine

- Skin cleaning agents such as chlorhexidine 2%

- A pulse oximeter, EKG monitor, and blood pressure monitor

- Ultrasound, sterile ultrasound transducer cover, and ultrasound gel

- Block needle: preferentially 20 to 22-gauge, 5 to 15 cm

Personnel

Trained and skilled medical providers, including anesthesiologists, can perform TAP blocks. Typically, a second healthcare provider or nurse is required for a timeout before starting the procedure and to assist with the injection of local anesthetic.

Preparation

The clinician must discuss the risks, benefits, and alternatives with the patient and obtain informed consent. The patient should be monitored using continuous EKG, continuous pulse oximetry, and blood pressure cuff cycling every 5 minutes. The patient should have IV access before the procedure. Position the patient supine and uncover the abdomen. Be sure to thoroughly clean the skin over the anterolateral abdomen, from the costal margin to the iliac crest, followed by sterile towels surrounding the border of the procedural field. A procedural time-out should take place before starting the procedure.

Technique or Treatment

Landmark-based TAP blocks are an uncommon choice, as an ultrasound machine is commonly available and has made regional anesthesia blocks safer and more reliable. Rafi first described the landmark-based technique. Using surface landmarks, the practitioner must identify Petit's lumbar triangle, which is medially bound by the external oblique, inferiorly by the iliac crest, and posteriorly by the latissimus dorsi.[5] Once the triangle is identified, and upon introducing the needle through the skin, a "double-pop" sensation, described by McDonnell, can be felt by the practitioner as the needle traverses through the fascia deep to the external oblique muscle (first pop), followed by penetration through the fascia deep to the internal oblique muscle (second pop).[2] At this point, the practitioner, after confirming negative aspiration for blood, injects local anesthetic incrementally, aspirating every few milliliters to reduce the risk of intravascular injection. It is common for patients to have a dull, pressure-like sensation during injection. See Image. Transverse Abdominis Plane Block.

Using a high-frequency linear or curvilinear ultrasound transducer orientated transversely, begin scanning the abdomen between the iliac crest and the costal margin at the mid-axillary line.[4] Note that the most superficial layer on ultrasound is skin and subcutaneous fat. The most superficial of the 3 muscular layers is the external oblique, the internal oblique, and the transversus abdominis muscle. The internal oblique is classically the thickest layer in most patients, while the transversus abdominis muscle is often the thinnest. If uncertain, increase the depth of the ultrasound to confirm the bowel beneath the transversus abdominis muscle, and be sure to avoid placing the needle in this region. Posteriorly scanning the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles shows the 2 layers come together to form the thoracolumbar fascia. Scanning medially, the aponeurosis of the 3 muscle layers can be seen coming together to form the rectus sheath. Upon identifying the TAP, numb the patient's skin using lidocaine, then penetrate the skin with the block needle using an in-plane technique, making sure to visualize the needle tip on ultrasound throughout its entire trajectory. Upon entering the TAP between the internal oblique and the transversus abdominis muscles, the local anesthetic is slowly and incrementally injected after negative aspiration for blood.

The TAP begins to "unzip" as the local anesthetic is injected, pushing the transversus abdominis muscle deeper. Depending on the patient’s weight and the concentration of the local anesthetic, an injection of 15 to 20 ml of local anesthetic is typical. This technique describes a posterior TAP block, which is the most commonly performed. Suppose a higher dermatomal coverage is required (T6-T9). The same technique can be used in the subcostal region, just medial to the anterior axillary line where these nerves enter the abdominal wall. Local anesthetic spread along the TAP is thought to be responsible for the efficacy of the block, as shown by radiological studies.[6][7] Experience has shown that the efficacy of the block is improved when injecting 15 ml or more.[8] TAP blocks can be done bilaterally or unilaterally, depending on the location of the surgery. A surgeon may also perform an abdominal wall block inside the abdominal cavity during surgery.[9]

Complications

Complications related to TAP blocks are rare. Given that abdominal wall blocks are field blocks, relying primarily on the volume of the local anesthetic to facilitate adequate blockade rather than targeting a specific nerve, neurological injury is rare. Neurologic injury may arise due to direct nerve trauma from the needle, hematoma, or local infection. Excessive needle insertion may also lead to complications such as intraperitoneal injection, visceral trauma, vascular injury, and liver trauma. Reports have also described transient femoral nerve palsy.[10] Ultrasound guidance helps to minimize these complications and is considered superior to landmark-based techniques that rely on subjective tactile pops through fascial planes. It is essential to recognize that local anesthetic injection within TAP occurs in a well-vascularized area. Therefore, one should be cautious to avoid vascular puncture and intravascular injection. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity is a rare but known complication.

Clinical Significance

TAP blocks have become an important addition to multimodal pain management for abdominal wall surgery. Their safety, ease, and effectiveness make them an excellent adjunct to perioperative pain management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

A team-based, interprofessional methodology should be implemented to ensure patient safety. Communication with the surgeon should take place to help assess the suitability of the block, along with specific details regarding the location of the incision, the timing of the block, and other unique considerations. An appropriate time-out to promote patient safety is necessary before the start of the procedure. Maintaining meaningful verbal contact with the patient throughout the procedure is vital to monitor for any complications such as local anesthetic systemic toxicity, potential nerve injury, or visceral perforation. Practitioners should take extreme caution when handling sharps, as accidental needle sticks may occur. Sharps require disposal using appropriately marked bins. Documentation of the procedure should include informed consent, date, time, procedure location, block technique, the medication used, volume and concentration of injectate, equipment used, ultrasound images, and documentation of any complications.

The interprofessional team includes clinicians (general and specialists), nurses, surgical assistants, and pharmacists. The clinician should send the patient to the specialist, who prepares the patient for the procedure in conjunction with the nursing staff. The pharmacy prepares the anesthetic and can be a resource for any medication-related questions by the team. Nursing assists during the procedure; additional nursing duties are outlined below. This interprofessional team paradigm optimizes the results from a TAP block, leading to better patient outcomes.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The nurse is in charge of setting up the instrument tray for the block, positioning and preparing the patient for the procedure, and ensuring that the patient has signed consent and that the procedure is taking place on the correct side of the abdominal pathology.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Before starting the procedure, the nurse must ensure that resuscitative equipment is in the room. One nurse should be dedicated to monitoring the patient during and after the procedure. In the recovery room, the nurse should assess the patient's hemodynamic status and evaluate the site of the block for bleeding.