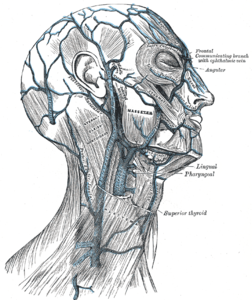

[1]

Kiliç T, Akakin A. Anatomy of cerebral veins and sinuses. Frontiers of neurology and neuroscience. 2008:23():4-15

[PubMed PMID: 18004050]

[2]

Bechmann S, Rahman S, Kashyap V. Anatomy, Head and Neck, External Jugular Veins. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:():

[PubMed PMID: 30855810]

[3]

Shimizu Y, Imanishi N, Nakajima T, Nakajima H, Aiso S, Kishi K. Venous architecture of the glabellar to the forehead region. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2013 Mar:26(2):183-95. doi: 10.1002/ca.22143. Epub 2012 Aug 7

[PubMed PMID: 22887451]

[4]

Sugahara K,Matsunaga S,Yamamoto M,Noguchi T,Morita S,Koyachi M,Koyama Y,Koyama T,Kasahara N,Abe S,Katakura A, Retromandibular vein position and course patterns in relation to mandible: anatomical morphologies requiring particular vigilance during sagittal split ramus osteotomy. Anatomy

[PubMed PMID: 33214345]

[5]

Kagaya Y, Arikawa M, Akazawa S. Superficial Temporal Vein and Alternative Middle Temporal Vein as Recipient Veins for Free-flap Reconstruction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2022 Mar:10(3):e4170. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004170. Epub 2022 Mar 8

[PubMed PMID: 35284200]

[6]

Sharma A Sr, Sharma M. Sinus Pericranii (Parietal and Occipital) With Epicranial Varicosities in a Case of Craniosynostosis. Cureus. 2022 Feb:14(2):e21891. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21891. Epub 2022 Feb 4

[PubMed PMID: 35273853]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[7]

Kobayashi S, Nagase T, Ohmori K. Colour Doppler flow imaging of postauricular arteries and veins. British journal of plastic surgery. 1997 Apr:50(3):172-5

[PubMed PMID: 9176003]

[8]

Hedjoudje A,Piveteau A,Gonzalez-Campo C,Moghekar A,Gailloud P,San Millán D, The Occipital Emissary Vein: A Possible Marker for Pseudotumor Cerebri. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2019 Jun;

[PubMed PMID: 31072972]

[9]

Chang L, Zixiang Y, Zheming F, Gongbiao L, Zhichun L, Rong Z, Aidong Z, Shuzhan L. Management of pterygoid venous plexus hemorrhage during resection of a large juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: a review of 27 cases. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2013 Apr-May:92(4-5):204-8

[PubMed PMID: 23599103]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[10]

Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights into imaging. 2016 Feb:7(1):69-76. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0454-5. Epub 2015 Dec 10

[PubMed PMID: 26661849]

[11]

Koeller KK, Alamo L, Adair CF, Smirniotopoulos JG. Congenital cystic masses of the neck: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1999 Jan-Feb:19(1):121-46; quiz 152-3

[PubMed PMID: 9925396]

[12]

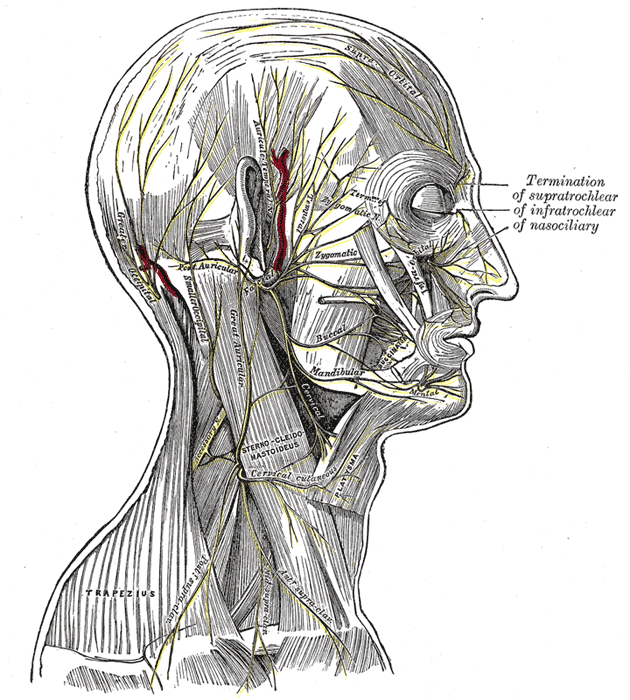

Kemp WJ 3rd,Tubbs RS,Cohen-Gadol AA, The innervation of the scalp: A comprehensive review including anatomy, pathology, and neurosurgical correlates. Surgical neurology international. 2011;

[PubMed PMID: 22276233]

[13]

Chen Z, Feng H, Zhu G, Wu N, Lin J. Anomalous intracranial venous drainage associated with basal ganglia calcification. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2007 Jan:28(1):22-4

[PubMed PMID: 17213417]

[14]

Gulmez Cakmak P, Ufuk F, Yagci AB, Sagtas E, Arslan M. Emissary veins prevalence and evaluation of the relationship between dural venous sinus anatomic variations with posterior fossa emissary veins: MR study. La Radiologia medica. 2019 Jul:124(7):620-627. doi: 10.1007/s11547-019-01010-2. Epub 2019 Mar 2

[PubMed PMID: 30825075]

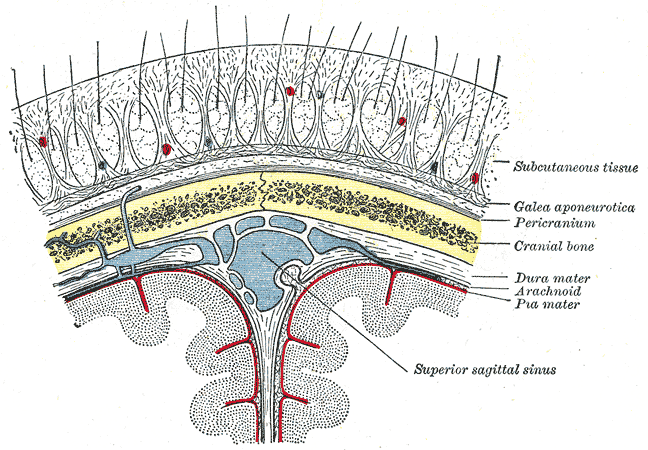

[15]

Yoon J, Puthumana JS, Nam AJ. Management of Scalp Injuries. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2021 Aug:33(3):407-416. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2021.05.001. Epub 2021 Jun 3

[PubMed PMID: 34092461]

[16]

Scalp Arteriovenous Malformation (Cirsoid Aneurysm) in Adolescence: Report of 2 Cases and Review of the Literature., Li D,Heiferman DM,Rothstein BD,Syed HR,Shaibani A,Tomita T,, World neurosurgery, 2018 Aug

[PubMed PMID: 29864562]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[17]

Matsushige T, Kiya K, Satoh H, Mizoue T, Kagawa K, Araki H. Arteriovenous malformation of the scalp: case report and review of the literature. Surgical neurology. 2004 Sep:62(3):253-9

[PubMed PMID: 15336874]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[18]

Lee SJ, Kim JK, Kim SJ. The clinical characteristics and prognosis of subgaleal hemorrhage in newborn. Korean journal of pediatrics. 2018 Dec:61(12):387-391. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2018.06800. Epub 2018 Sep 16

[PubMed PMID: 30304906]

[19]

Caranfa JT, Yoon MK. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis: A review. Survey of ophthalmology. 2021 Nov-Dec:66(6):1021-1030. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2021.03.009. Epub 2021 Apr 5

[PubMed PMID: 33831391]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[20]

Matthew TJH,Hussein A, Atypical Cavernous Sinus Thrombosis: A Diagnosis Challenge and Dilemma. Cureus. 2018 Dec 4;

[PubMed PMID: 30761237]