Continuing Education Activity

Injuries of the pectoralis major muscle are rare. Although the injury typically occurs while lifting weights, specifically while performing a bench press, it has also been known to occur in several other sports. Several factors, including delay in care and recognition of the injury, can delay appropriate treatment and result in worse outcomes for the patient. Specific treatment of this injury depends on the severity of the injury, the patient’s activity level, and daily living needs. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment and reviews the role of the healthcare team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Outline the typical presentation of a patient with a pectoralis major tear.

- Review the common physical exam findings associated with a pectoralis major tear.

- Describe the appropriate treatment options for a pectoralis major based on the grading of the injury.

- Explain the importance of improving care coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients with a pectoralis major tear.

Introduction

Injuries of the pectoralis major muscle are rare. Although the injury typically occurs while lifting weights, specifically while performing a bench press, it has also been known to occur in several other sports.[1] Several factors, including delay in care and recognition of the injury, can delay appropriate treatment and result in worse outcomes for the patient. Specific treatment of this injury depends on the severity of the injury, the patient’s activity level, and daily living needs.

Etiology

A pectoralis major lesion occurs when there is tearing of the pectoralis major muscle due to excessive tension on a maximally eccentrically contracted muscle or, less commonly, as a result of direct trauma.[2]

Epidemiology

The injury most commonly occurs in young, physically active males in the third and fourth decades of life.[1] It is often associated with weight lifting (particularly bench press), although there are reports of the injury during various other activities, such as martial arts, gymnastics, and football. It also has correlated with anabolic steroid use.[3]

Pathophysiology

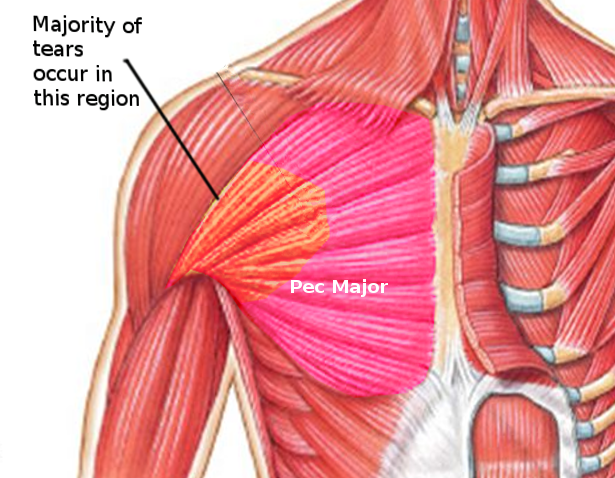

The pectoralis major is a broad, fan-shaped muscle that covers the upper anterior portion of the chest. The innervation corresponds to the lateral (C5-C7) and medial (C8-T1) pectoral nerves. It is composed of two parts: a sternal head and a clavicular head. The origin of the sternal head is the sternum and the six superior costal cartilages. The origin of the clavicular head is the medial half of the clavicle. The insertion of both is within an anterior and posterior layer at the lateral lip of the bicipital groove of the humerus. The action of the muscle is adduction, forward elevation, and internal rotation.[4]

Traumatic injury of the pectoralis major most commonly occurs due to excessive tension on a maximally eccentrically contracted muscle. This setup typically occurs during the downward portion of a bench press, with the arm in the final 30 degrees of humeral extension and external rotation while pushing against heavy resistance. The most common types of injuries of the pectoralis major muscle are tendon avulsions at the site of insertion by this mechanism. Less common are myotendinous junction tears due to direct trauma.[4]

History and Physical

The patient history should denote the mechanism of injury, as most patients recall the specific incident that led to the injury.[5] Patients will usually report a tearing sensation or a “pop,” accompanied by a painful limitation of motion, as well as localized swelling, asymmetry, and ecchymosis. Delayed presentations often result from patients initially treating the injury at home as a typical sprain or strain rather than seeking medical care.

The physical examination may demonstrate swelling and ecchymosis over the anterior chest wall, axilla, and arm. Further inspection may reveal an asymmetric medial prominence of the muscle belly or a thinned-out, webbed appearance of the anterior axilla. Palpation may elicit tenderness over the insertion along the axillary fold, which may itself be thinned, hollowed, or completely lost. This finding can be accentuated by abducting the arm to 90 degrees.[5] Strength and range-of-motion testing may reveal the limitation of shoulder motion due to pain and weakness in adduction and internal rotation of the arm.

Evaluation

Plain radiographs are of limited utility in diagnosing a pectoralis major tear but should be performed to assess for other pathology or associated abnormalities, such as bony avulsion injuries that occur in 2% to 5% of cases.[1][6]

Ultrasound can be useful due to its relatively low cost and rapid availability. Tears are often identifiable by uneven echogenicity and muscle tearing in comparison with the contralateral side. The utility of ultrasound for this application, however, remains somewhat controversial, with some authors contending that the false-negative rate is unacceptably high.[7]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered the imaging modality of choice and can help differentiate between acute or chronic complete or partial tears. MRI can be used to assess the grade and site of injury and correlates well with surgical findings.[8][9]

Tietjen, in 1980, developed a system for classifying the location and severity of the injury.[10] Tietjen denoted type I injuries as those consisting of muscle contusions and tears, type II as partial tears, and type III as complete tears. The latter category is further subdivided by location as follows: A) sternoclavicular origin; B) muscle belly; C) myotendinous junction; D) insertion.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of a pectoralis major tear depends on the severity of the injury and the anticipated use of the injured muscle based on the activity level of the patient (e.g., an athlete involved in competitive sports versus a sedentary individual performing activities of daily living). The treatment of choice for complete tears is generally operative. Initial non-operative treatment involves rest, ice, analgesia, and immobilization in a sling with the arm adducted and internally rotated.[11][12] Passive and active range of motion exercises should begin within the first two weeks of recovery, gradually increasing to a full range of motion over the next six weeks. Progressive resistance exercises can begin at six to eight weeks from the date of injury, gradually increasing until full resistance training can resume at three to four months post-injury.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis includes:

- Rupture of the long head of biceps tendon

- Shoulder dislocation

- Proximal humerus fracture

- Rotator cuff tendon tear

- Subscapularis muscle tear

- Medial pectoral nerve entrapment

Prognosis

The prognosis of pectoralis major tears is generally good, especially if a prompt diagnosis is made and appropriate treatment is administered. Several studies have compared operative and non-operative management and concluded that operative management generally results in better functional recovery, including peak torque and work performance.[3][6][12][13][14]

Complications

Complications of non-operative management

- Persistent weakness

- Cosmetic deformity

- Hematoma

- Abscess formation

- Myositis ossificans

Complications of operative management

- Infection

- Hypertrophic scar

- Stiffness

- Re-rupture

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be aware of diminished strength and worse outcomes with non-operative treatment.[6] The aesthetic result is also generally not favorable if this pathology is not treated surgically.[14]

Pearls and Other Issues

Presentation to a healthcare provider often gets delayed as patients treat the injury like a typical strain or sprain. A pectoralis major tear can be more difficult to detect after the initial pain and swelling have subsided. Persistent weakness and asymmetry after the resolution of the initial symptoms usually suggest a more severe injury. In contrast, an acute pectoralis major tear may be more challenging to detect due to swelling, an intact fascial covering, or the overlying and uninjured clavicular head obstructing a palpable or visible defect.[5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pectoralis major tears are rare injuries, and there may be a delay in the presentation to the emergency department or primary care provider. To improve the morbidity of the disorder, an interprofessional team approach is a recommendation. Healthcare practitioners should order an MRI if a pectoralis major tear is suspected. The patient should obtain a referral to a sports physician, orthopedic surgeon, or rehabilitation specialist. Early diagnosis and treatment are important as chronic injuries may lead to more technically difficult surgery and suboptimal outcomes.[1][15] The pain may need to be managed by the practitioner. Patients need to be educated on the adverse effects of analgesics and should opt for non-pharmacological measures like ice, massage, and acupressure. For those who are young, active, and want a faster recovery, referral to an orthopedic surgeon is the proper course. The recovery after conservative treatment is often long; after surgery, the recovery is faster, but there is always the risk of complications. Irrespective of the approach, the patient should be encouraged to seek physical therapy. The outcomes in most patients are good. Orthopedic specialty-trained nurses can assist with either surgical or conservative care, and act as a bridge between physical therapists and rehabilitation specialists and the surgeon. All members of the interprofessional healthcare team must communicate and have access to the same level of information regarding the case to drive optimal patient outcomes.[Level V]