Continuing Education Activity

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are often seen in the body and tail region of the pancreas in middle-aged women. They are considered premalignant lesions and require surgical excision depending on the size and imaging features. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of mucinous cystadenoma of the pancreas and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in surveillance and surgical treatment including post-surgical complications.

Objectives:

Describe the imaging features of mucinous cystadenoma of the pancreas.

Outline the diagnostic algorithm of a 5 cm cystic lesion found on ultrasonography in the body of the pancreas.

Identify the suspicious features of the imaging of a cystic neoplasm of the pancreas.

Review the importance of improving care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients diagnosed with a cystic lesion of the pancreas.

Introduction

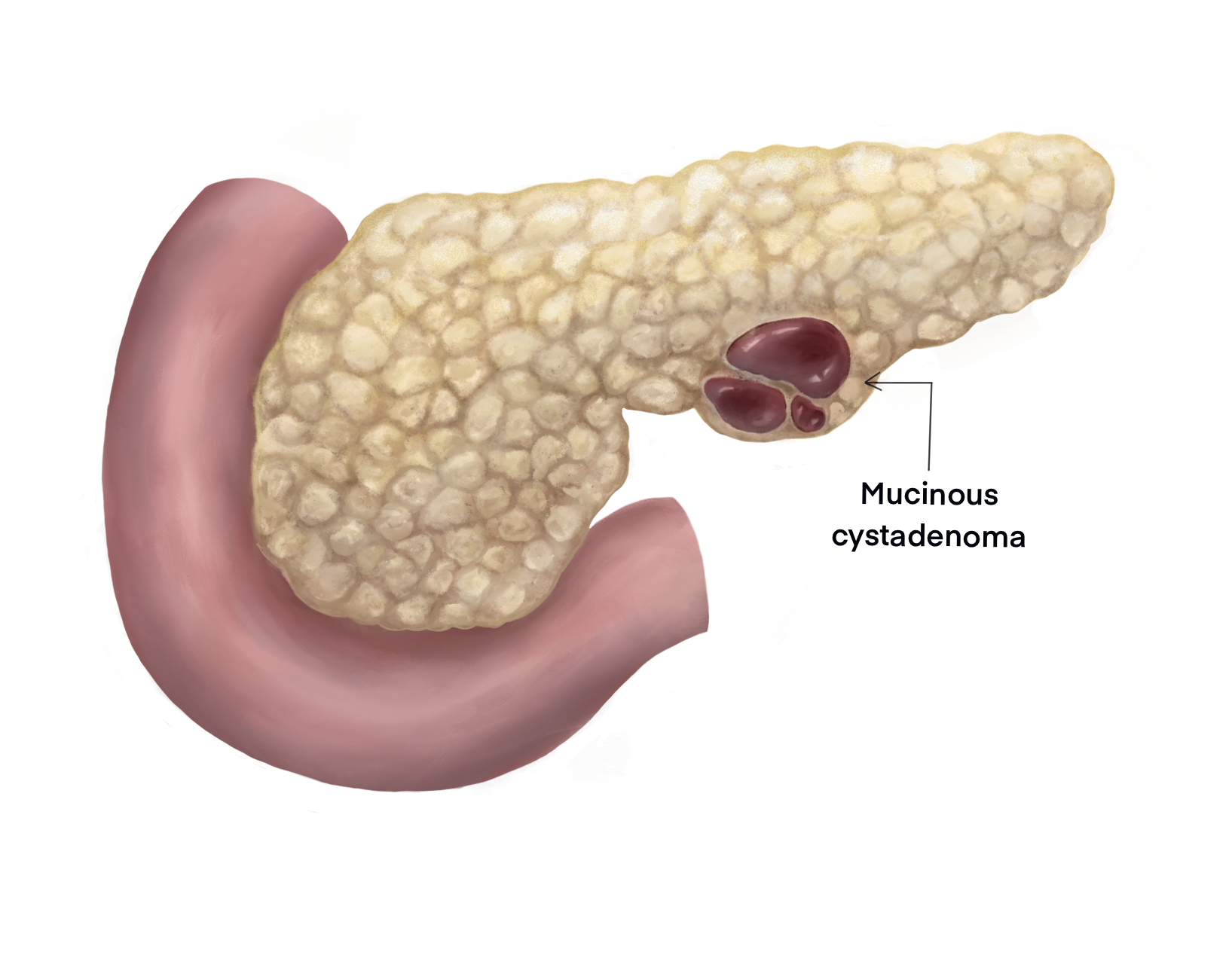

Mucinous cystadenoma (MCN) is an epithelial neoplasm producing mucin and forming cysts arising from the pancreas. They account for nearly half of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas, with the others being serous cystadenoma (SCN) and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). MCNs and IPMN have features in common like cyst formation, mucin production, and progressing to invasive carcinoma. Most often, MCNs are located in the body and tail region of the pancreas, and they are often found incidentally.[1] MCNs are noticed most frequently in females, and they usually present in a young woman without any previous history or risk factor for pancreatitis. Investigations preferably include magnetic resonance imaging or contrast-enhanced computed tomography supplemented by endoscopic ultrasound with cyst fluid aspiration. MCNs are premalignant neoplasms and surgical excision is preferred. A completely excised cyst that has no features of carcinoma rarely recur and do not warrant a regular follow up.[2]

Etiology

The exact origin of this neoplasm is still debated, with immunophenotype resembling ovarian type stroma. Research suggests the etiology may be stimulation by female hormones of immature endodermal stroma or implantation of primary yolk cells in the pancreas.[3][4] The most common and early genetic alteration occurring in MCN is the KRAS gene. SMAD4 and TP53 alterations are seen in invasive or high-grade lesions.

Epidemiology

MCNs are rare when compared to pseudocysts and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, with few studies reporting on epidemiology. Reportedly MCNs account for 29% of neoplastic cystic lesions of the pancreas. Predominantly MCNs are seen in females, and the mean age of diagnosis is between 40 to 50 years (range 4 to 95 years).[5][6] Virtually all MCNs occur in women, and it is rare to find these lesions in men. The majority of MCNs are found in the body and tail region of the pancreas.[5][7][8]

Pathophysiology

MCNs are well-encapsulated and usually large-ranging up to 25 cm. The origin is from the pancreatic ductal cell. MCNs can present as a spectrum from benign to borderline and, frankly, malignant lesions. They are usually slow-growing. MCNs lacking features of malignancy are considered to be premalignant.[9]

Histopathology

Mucin-producing cystic epithelial neoplasms with septations characterize mCNs. Fluid in the cyst, when aspirated, is usually thick and viscous. The cysts are lined by columnar epithelium, which may occur in a single layer, with some areas showing papillary projections or invaginations. The presence of ovarian stroma is the pathognomonic finding in an MCN. FNA cytology shows characteristic honeycomb sheets, with mucin-producing columnar cells in clusters and rich in mucin. MCNs do not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system, which is the fundamental differentiating character from IPMNs.[4][10] They usually occur solitarily.[4]

History and Physical

A combination of history and imaging increases diagnostic accuracy. Detailed information to rule out pancreatitis is of utmost importance since MCNs can present with abdominal pain, recurrent pancreatitis, gastric outlet obstruction, jaundice, or weight loss. However, cystic neoplasms, by and large, are diagnosed incidentally.[8] The examination may reveal a lump in the upper abdomen in an occasional patient.

Evaluation

Imaging

Imaging plays a crucial role in diagnosing MCNs. Imaging is done to determine the specific cyst type and to establish features of malignant transformation.

1. Transcutaneous ultrasound may be useful occasionally, but a deep-seated pancreas is not always visualized in its entirety.

2. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is preferred to CT where available, as it is more sensitive for demonstrating ductal communication and internal architecture. A contrast-enhanced CT (pancreatic protocol) can also provide information and typically shows a septated cystic lesion or rarely a unilocular lesion as an initial assessment.

Typically, on MRI, MCNs appear as oligocellular, micro, or macrocytic and occupying the body and tail region of the pancreas. Since MCNs contain fluid in their cystic cavities, T2-weighted images are hyperintense. MRI also demonstrates if any ductal communication exists.

Features suggesting malignant transformation include:[8][11][12]

- Thickened wall

- Internal solid component or mass

- Possible calcification of the cyst wall.

3. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) gives a better evaluation of the cyst wall and evaluates for any nodules. EUS can also be used for aspirating cyst fluid for analysis. Suspicious features include diameter >3 cm, mural nodules, thick and irregular walls, and an obstructed pancreatic duct.

4. The role of F-18 FDG positron-emission tomography is still not defined in MCNs and is still being investigated.

Cystic Fluid

1. Fluid CEA levels >192 ng/mL has up to 79% accuracy in differentiating mucinous from non-mucinous cystic neoplasms.[13] A high CEA in the cyst fluid also suggests malignancy.

2. Aspirated fluid from the cyst has to be sent for cytology to evaluate for the presence of dysplasia or cancer, more so when imaging features are inconclusive.

Treatment / Management

1. MCNs have a substantial risk for malignancy. Treatment of MCNs is surgical resection.[14] Resection is recommended in a patient with the following findings:

- Symptomatic MCNs irrespective of size

- MCNs of size > 4.0 cm

- MCNs with suspicious features irrespective of size

If there is no suspicion of carcinoma, a spleen preserving or parenchyma sparing procedure (non-oncologic resection) can be performed. Minimally invasive procedures involving laparoscopic and robotic distal pancreatectomies are equally acceptable with similar oncologic outcomes and with the benefits of laparoscopy.[2][15][16]

MCNs with suspicious features should undergo standard oncologic resection, mostly involving distal pancreatico-splenectomy and lymph node dissection.

For asymptomatic MCNs of 3 to 4 cm, treatment must be individualized considering the patient's age, surgical risk, and patient's preference. Since determining the nature of a <3cm cystic lesion is difficult, the recommendation is for surveillance.

2. Surveillance recommendations include MRI, EUS, or a combination of both every 6 months during the first year. If no changes are noted, then imaging can be done annually during their lifetime as long as they are deemed fit to undergo surgery.

The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines suggest an imaging schedule based on the size of the cyst.[15]

- <1 cm - MRI in 2 years.

- 1-2 cm - MRI in 1 year.

- 2-3 cm - MRI or EUS in 6 to 12 months

During surveillance, if a patient develops jaundice, acute pancreatitis, elevated serum CA19-9, mural nodules, or an increase in the size of the lesion, they will need EUS with FNA and multidisciplinary panel referral.[15]

3. Cyst ablation with ethanol or paclitaxel injection and radiofrequency ablation has been studied but is not the standard of care at present.[15]

In summary, the patient's risk of developing a malignancy needs to be assessed against the risks of undergoing surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

The most important differential diagnosis for MCNs are other cystic lesions of the pancreas

- Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN)

- Serous cystadenoma

- Pancreatic pseudocyst

- Solid pseudopapillary tumor

- Retention cyst

- Simple mucinous cyst

Prognosis

After complete resection and in the absence of any invasive component on histopathological examination, the prognosis is excellent with an overall survival rate of 100%, and patients usually do not need any follow-up.[8][17]

Complications

Morbidity of up to 50% is reported in various studies of which postoperative pancreatic fistulae are bothersome and require prolonged drainage. Though most fistulae are managed with intraoperatively placed drains, if they persist beyond 14 days, then endoscopic retrograde pancreaticography would be diagnostic, and a stent can be placed to decrease the drain output.[18]

Other complications include hemorrhage, which may require an interventional radiology consult or surgical intervention depending on the severity of the bleed.

Up to 20% of patients may be expected to develop new-onset diabetes mellitus after distal pancreatectomy and up to 10% in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients undergoing resection for an MCN constituting a distal pancreatectomy or pancreaticoduodenectomy may develop diabetes mellitus by up to 20%. The patients need to be made aware and educated. Though having a resection for a confirmed benign lesion is unlikely to recur and does not mandate a follow-up. Whereas patients undergoing surgery for lesions with suspicious characteristics need regular follow-up with imaging.

Pearls and Other Issues

Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas have undergone extensive research and have now been classified into well-defined categories, with recommended management strategies.

A middle-aged woman with a cystic lesion in the body and tail region of the pancreas very likely has a mucinous cystic lesion of the pancreas.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Mucinous cystadenoma, though uncommon, constitutes about 27% of cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. A detailed evaluation with CT and/or MRI abdomen and discussion with the radiologist to rule out suspicious features is pertinent to plan surgical strategy. When imaging is inconclusive, a gastroenterologist may be involved in performing endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to characterize the cyst and its relation to the vessels. EUS can also be used simultaneously for the aspiration of cyst fluid to be sent for analysis. Since the condition is more often seen in a comparably younger age group, most patients are fit to undergo surgery. However, a pre-anesthetic check-up is needed to assess the patient's fitness for surgery. Post-surgery patients need to be started on prophylactic thromboprophylaxis. The patient also needs to be started on a spirometer, and physiotherapy for early ambulation is carried out.

Drains kept intra-operatively should be diligently monitored for the quantity and character of the fluid. If this is high, drain fluid amylase needs to be obtained. If the patient has a pancreatic fistula, then the drain is to be kept for a longer duration until the output decreases to less than 30-50 ml. The patient may be discharged with the drain in place if the output is high and the patient is tolerating an oral diet. Further follow-up and care by the supportive staff will be needed in this case.