Continuing Education Activity

Chest tubes are a critical intervention for managing pleural space pathologies, including pneumothorax, hemothorax, empyema, and postoperative drainage. Proper placement technique, tube selection, and securement are essential to minimize complications such as malposition, infection, and injury to surrounding structures. Monitoring tube function, assessing output characteristics, and timely removal based on clinical criteria are crucial for optimizing patient outcomes. The role of imaging in placement confirmation and troubleshooting complications is well-established, while evolving evidence suggests a more selective approach to postremoval chest x-rays. A multidisciplinary approach is necessary to ensure effective management, patient safety, and recovery.

This course equips clinicians with the knowledge and skills needed for safe and effective chest tube management. Participants learn the best insertion, securement, maintenance, and removal practices while developing competency in recognizing and addressing complications. Emphasis is placed on interprofessional communication and coordination to enhance patient-centered care. Clinicians also gain insight into recent evidence-based guidelines, including tube removal criteria and selective postremoval imaging use. By completing this course, providers will be better prepared to implement standardized, efficient, and safe chest tube management strategies in emergency and elective settings.

Objectives:

Identify indications and contraindications for chest tube placement in various clinical scenarios.

Screen patients for potential complications associated with chest tube placement and management.

Assess the proper positioning of a chest tube using imaging modalities such as chest x-ray or ultrasound.

Collaborate with interprofessional teams, including physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists, to optimize patient outcomes.

Introduction

Chest or thoracostomy tubes are flexible devices that drain air, fluid, or blood from the pleural space, facilitating lung reexpansion and restoring normal intrathoracic pressure dynamics. Typically constructed from polyvinyl chloride or silicone, chest tubes range in size from 6 to 40 Fr and are fenestrated along the insertion end, often with a radiopaque stripe to enhance visibility during imaging. Once inserted, the distal end of the tube is connected to a wet suction control system comprising 3 chambers: the suction chamber, the water seal chamber, and the collection chamber. The water seal chamber functions as a 1-way valve, allowing air to exit but preventing reentry into the thoracic cavity. Heimlich valves, another tool for pleural drainage, serve as portable 1-way valves for preventing backflow into the pleural space, making them suitable for outpatient care.

Indications for chest tube placement span a variety of clinical scenarios, including pneumothorax, hemothorax, pleural effusion, empyema, and post-surgical management of thoracic procedures. In emergent and elective settings, chest tubes are crucial for managing thoracic injuries, pleural diseases, or complications requiring drainage. Their utility extends to both short-term hospital-based care and long-term outpatient pleural drainage. Effective management necessitates a multidisciplinary approach involving various clinicians, including physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, imaging specialists, and other healthcare professionals. This collaborative effort ensures proper placement, minimizes complications, and optimizes patient outcomes.

Insertion and management of chest tubes require careful assessment and technical precision. Clinicians, often surgeons or emergency physicians, determine the indications for placement and ensure proper positioning, frequently guided by imaging modalities such as ultrasound or computed tomography. Nursing staff are critical for ongoing care, monitoring the tube and drainage system, while respiratory therapists support ventilated patients. Imaging specialists contribute by guiding placement and assessing the need for additional interventions, such as tube repositioning or removal. Advanced procedures may be required in complex cases, including pleurodesis, thoracoscopic surgery, thoracotomy, lung resections, or bronchoscopic interventions.

This activity explores the essential principles of chest tube management, including equipment, indications, insertion techniques, and the roles of interdisciplinary care. Emphasis is placed on evidence-based practices, strategies to prevent complications, and technological innovations to improve patient safety and outcomes. By addressing these aspects, this activity aims to provide a comprehensive resource for optimizing chest tube care in thoracic medicine.

Anatomy and Physiology

Chest tubes, or thoracostomy tubes, are vital tools for managing disruptions in the pleural space, such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, or pleural effusion. A comprehensive understanding of the pleural space's applied anatomy, physiology, pathology, and pathophysiology is essential for effectively caring for patients requiring chest tube placement.

Anatomical Considerations

The pleural space, a potential cavity between the visceral and parietal pleura, is integral to normal respiratory function. These mesothelial membranes are contiguous at the hilum of the lung:

- Visceral pleura

- Covers the lung's surface

- Parietal pleura

- Lines the thoracic wall, diaphragm, and mediastinum and contains sensory innervation

The pleural space normally holds a small amount of serous fluid (~10–20 mL) to facilitate frictionless lung movement during respiration and maintain negative pressure, which supports lung expansion. Disruptions in this pressure can severely impair respiratory mechanics, necessitating intervention.

Chest tubes are typically inserted into the safe triangle, bounded by:

- Anterior edge of the latissimus dorsi

- Lateral edge of the pectoralis major

- The fifth intercostal space (or nipple line) with the apex of the triangle in the axilla [1]

Surface anatomical landmarks, such as the sternal angle (second intercostal space) and nipple (fourth intercostal space), assist in identifying the appropriate insertion site—commonly the fifth intercostal space, between the anterior and midaxillary lines (see Image. Chest Tube). The tube should be positioned along the upper border of the rib below to avoid the neurovascular bundle located on the lower border of the rib above. The mediastinum, which houses the heart, great vessels, and other critical structures, also occupies the central thoracic compartment. Care must be taken to direct the tube away from these vital mediastinal structures.

Physiological Considerations

The pleural space's negative pressure enables lung expansion and effective ventilation. Pathological conditions can disrupt this dynamic:

- Pneumothorax

- Air entering the pleural space from the chest wall, lung parenchyma, or bronchial tree impairs lung expansion.

- A tension pneumothorax arises when air accumulates via a 1-way valve mechanism, causing progressive lung collapse, mediastinal shift, and reduced venous return to the heart. This can lead to cardiopulmonary compromise, with tracheal deviation to the contralateral side as a pathognomonic sign.

- Pleural effusion

- Fluid accumulation in the pleural space, caused by conditions like heart failure, pneumonia, or malignancy, compresses lung tissue and impairs gas exchange. Loculated effusions due to pleural fibrosis require precise tube placement.

- Hemothorax and chylothorax

- Blood or lymphatic fluid in the pleural space also disrupts respiratory mechanics, requiring evacuation.

Mechanism of Chest Tube Function

Chest tubes restore normal pleural dynamics by evacuating air, fluid, or blood and preventing air reentry:

- Air removal

- In a pneumothorax, chest tubes connected to underwater (water seal) drainage systems allow air to escape while maintaining negative pressure in the pleural space.

- Fluid drainage

- Chest tubes remove accumulated fluid from pleural effusions, hemothorax, and chylothorax, reducing lung compression and improving ventilation.

- Pressure maintenance

- Suction systems maintain appropriate pleural pressure to optimize lung reexpansion.

Applied Anatomy and Pathology

The pleural space's anatomy and pathology necessitate careful technique during chest tube placement:

- Pain management

- Anesthetizing the skin, subcutaneous tissues, and parietal pleura is crucial for mitigating pain caused by the parietal pleura's sensory innervation.

- Avoiding complications

- Adhesions between the lung and pleura, caused by chronic disease or fibrosis, increase the risk of intraparenchymal placement or lung injury. Proximity to other structures—including mediastinal vessels, the heart, esophagus, diaphragm, liver, spleen, and stomach—requires meticulous attention to minimize iatrogenic injury.

Indications

Chest tubes evacuate air, fluid, blood, or infectious material from the pleural space, restore pulmonary function, and maintain pleural integrity. They are also used to introduce therapeutic agents into the pleural cavity. The primary indications include:

- Pneumothorax

- Spontaneous pneumothorax

- Occurs without trauma, often in individuals with underlying lung conditions or in tall, thin individuals.

- Chest tube drainage remains the reference first-line treatment of primary spontaneous pneumothorax.[2]

- Tension pneumothorax

- This is a medical emergency caused by progressive accumulation of air in the pleural space, leading to lung collapse, mediastinal shift, impaired venous return, and cardiopulmonary compromise.

- Traumatic or iatrogenic pneumothorax

- This results from penetrating or blunt trauma or secondary to diagnostic and therapeutic pulmonary procedures.[3]

- New guidelines on primary spontaneous pneumothorax suggest ambulatory approaches may be suitable. However, guidance on iatrogenic pneumothorax occurring in patients with impaired lung function, increased age, comorbidity, and frailty is lacking, and the safety profile of ambulatory management is not known.[3]

- Pleural effusion

- Exudative effusion

- Associated with infections, malignancies, or inflammatory diseases

- Transudative effusion

- Often due to systemic conditions like heart failure, liver cirrhosis, or nephrotic syndrome

- Hemothorax

- Blood accumulation in the pleural space that is commonly due to trauma or complications of surgery

- Empyema

- The infection leads to pus accumulation within the pleural space, often requiring drainage to resolve the infection and prevent fibrosis.

- Chylothorax

- Accumulation of lymphatic fluid (chyle) in the pleural space, often due to thoracic duct injury or obstruction

- Postsurgical or posttraumatic drainage

- Following thoracic surgery (eg, lobectomy, pneumonectomy) or chest trauma to prevent fluid or air accumulation and ensure proper lung reexpansion

- Malignant pleural effusions

- Recurrent effusions associated with advanced malignancy requiring drainage to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life

- Bronchopleural fistula

- The abnormal connection between the bronchial tree and pleural space leads to air leakage and necessitates drainage.

- Hydropneumothorax

- The presence of both air and fluid in the pleural space requires the placement of a chest tube for drainage and lung expansion.

- Introduction of therapeutic agents

- Warm saline pleural lavage

- Used for internal rewarming in cases of hypothermia

- Sclerosing agent for pleurodesis

- Administered to achieve chemical pleurodesis for recurrent pleural effusions or pneumothorax

- Hyperthermic intrathoracic chemotherapy

- Used to treat pleural involvement in malignancies such as mesothelioma, thymoma, or metastatic disease, delivering targeted chemotherapy within the pleural cavity

Contraindications

While chest tubes are essential for managing various pleural and thoracic conditions, their placement may be contraindicated or require special consideration in some situations.

Absolute Contraindications

- Inability to provide safe access

- Scarring, fibrosis, or extensive adhesions in the pleural cavity may prevent successful tube placement or create a risk of injuring vital structures.

- Inexperienced operator without supervision

- A chest tube should not be placed by an untrained clinician in complex cases without expert supervision due to the high risk of complications.

Relative Contraindications

- Localized infections or skin issues at the insertion site

- Active cellulitis, abscess, or other infections over the entry site may increase the risk of introducing infection into the pleural space. An alternative insertion site should be considered.

- Uncorrected coagulopathy

- Patients with significant bleeding disorders (eg, low platelet count, elevated international normalized ratio) are at high risk for hemorrhage. If possible, correction of coagulopathy should be attempted before chest tube placement.

- Unstable or compromised anatomy

- Congenital or acquired anatomical abnormalities that significantly distort thoracic or pleural anatomy may preclude safe placement.

- Diaphragmatic hernias or intrathoracic abdominal organs

- Chest tube insertion may inadvertently damage herniated organs, such as the stomach, liver, or intestines. Imaging guidance may be necessary.

- Severe pulmonary disease

- Conditions like advanced pulmonary fibrosis or bullous emphysema may increase the risk of complications, such as lung puncture or air leaks.

- Bleeding risks

- Patients on anticoagulants or antiplatelet therapy are at increased risk of bleeding during and after chest tube placement. These medications should be managed appropriately before the procedure.

- Loculated or septated effusions

- Complex pleural effusions may limit the efficacy of chest tube drainage and require alternative interventions such as image-guided catheter placement.

- Clinically insignificant pneumothorax or effusion

- In asymptomatic individuals, observation or less invasive management (eg, needle aspiration) may be preferable to chest tube placement.

Special Considerations

- Mechanical ventilation

- Inserting a chest tube in patients on positive pressure ventilation requires extra caution, as the risk of pneumothorax or air leaks increases.

- Proximity to vital structures

- Care must be taken to avoid injuring nearby organs, including the heart, great vessels, liver, spleen, and diaphragm, particularly in patients with distorted anatomy or prior surgeries.

Equipment

Chest tube insertion, or thoracostomy, requires specific equipment to ensure a safe and effective procedure. Equipment for chest tube placement can vary depending on the clinical setting, patient acuity, indication, and provider practice patterns. Trauma resuscitation bays often have prepackaged thoracostomy trays, kits or carts readily available. The necessary items can be categorized into preparation, insertion, and drainage components.

Preparation Equipment

- Sterile field supplies

- Sterile drapes, gloves, and gown to maintain asepsis

- Sterile gauze and sponges are used to clean and cover the site

- Skin preparation

- Antiseptic solution (eg, chlorhexidine or iodine-based) to clean the insertion area

- Local anesthetic (eg, lidocaine) with syringes and needles for numbing the site

- Marking tools

- A sterile marker or pen to identify the incision site

Insertion Equipment

- Scalpel

- A sterile scalpel for making the incision

- Forceps

- Hemostats or curved Kelly forceps for blunt dissection of tissue and placement of the chest tube

- Chest tube

- A sterile chest tube of appropriate size (eg, 16-28 Fr for adults, smaller sizes for pediatric patients)

- A pigtail catheter, 8.5 Fr, 15 cm long, is used for percutaneous chest tube insertion. The shaft has holes, and an adaptor at the end allows connection to the underwater seal drainage system.

- Suture materials

- Nonabsorbable sutures (eg, silk) are used to secure the tube and close the incision site.

- Needle holder and scissors

- For suturing and trimming sutures

Drainage Equipment

- Drainage system

- A water-seal or dry-seal drainage system to collect fluid or air and prevent backflow into the pleural space

- Connecting tubing

- Sterile tubing to connect the chest tube to the drainage system

- Suction device (if required)

- Wall-mounted or portable suction is used to apply negative pressure to the drainage system

Additional Equipment

- Monitoring devices

- Pulse oximeter and blood pressure monitor for patient safety during the procedure

- Emergency supplies

- Equipment for resuscitation (eg, bag-valve-mask, oxygen supply) in case of complications

- Imaging support

- Portable chest x-ray or ultrasound for confirmation of placement and guidance if required

Postinsertion Supplies

- Dressing materials

- Occlusive dressings (eg, petroleum gauze or adhesive transparent dressing) prevent air leaks.

- Adhesive tapes are used to secure the dressing and chest tube.

- Drainage monitoring tools

- Graduated measuring devices quantify fluid output.

Personnel

A surgeon, pulmonary/critical care physician, emergency room physician, or interventional radiologist is the most likely proceduralist for placing a chest tube.

Preparation

Before performing a tube thoracostomy, several critical factors must be considered to optimize patient outcomes and minimize complications:

- Chest tube size

- Results from studies in trauma have shown no significant difference in outcomes between small-bore (20–22 Fr) and larger chest tubes, making smaller tubes a viable option, particularly for hemothorax and pneumothorax management. However, larger tubes (28–36 Fr) may still be preferred in cases of massive hemothorax or viscous effusions.[4]

- Drainage system

- Modern drainage systems are based on the original 3-bottle system, which is now integrated into single, self-contained units. The chest tube connects to the first chamber, which collects drainage. The second chamber is a water seal to prevent retrograde air or fluid movement, while the third regulates suction pressure.[5] Proper setup and maintenance of this system are essential for adequate drainage and lung reexpansion.

- Autotransfusion

- In cases of hemothorax, an autotransfusion system can be used to collect and reinfuse the patient’s own blood, reducing the need for allogeneic blood transfusion. This is particularly useful in trauma settings to minimize blood loss and associated complications.[6]

- Antibiotics

- Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended before chest tube placement, particularly in those with trauma, to reduce the risk of empyema and pneumonia.[7] However, prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis after tube placement has not been shown to decrease infection rates significantly and is generally not recommended.[8] Clinicians should adhere to evidence-based guidelines when considering antibiotic use for tube thoracostomy patients.

Technique or Treatment

The technique for chest tube placement involves a systematic approach to ensure safe and effective drainage of air, blood, or fluid from the pleural cavity while minimizing complications. This includes the following steps:

- Patient preparation and positioning

- Position the patient supine with the head of the bed elevated 30 to 45 degrees, with the ipsilateral arm abducted behind the head to expose the lateral chest wall.

- Identify the "triangle of safety" as the preferred insertion site: bordered by the lateral edge of the pectoralis major, the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi, and a line superior to the nipple (fourth to fifth intercostal space in the mid-to-anterior axillary line).

- Administer local anesthesia (1% lidocaine) at the insertion site, infiltrating the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and periosteum of the rib above the insertion site.

- Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered before placement in the elective operative or trauma setting to reduce the risk of infection.[7]

- Site selection and imaging guidance

- The fourth intercostal space is typically at the nipple level in males or the inframammary fold in females.

- Placement should be tracked above the rib to avoid the intercostal neurovascular bundle (artery, vein, nerve).

- Ultrasound or computed tomography guidance may be used in complex cases, such as patients with a history of infection, pleural disease, or prior surgery, to minimize complications and ensure proper placement.

- A soft tissue "flap" (by tracking the tube over 1 rib space) can help prevent persistent or recurrent pneumothorax after tube removal by reducing air reentry.

- Incision and dissection

- Make a 2 to 3-cm horizontal incision at the insertion site.

- Use a Kelly or Peon clamp to bluntly dissect through the subcutaneous tissue and intercostal muscles, following the natural direction of muscle fibers.

- The clamp is then used to bluntly penetrate the pleura, ensuring a controlled entry into the pleural space.

- A finger sweep is performed inside the pleural space to confirm entry, break up adhesions, and ensure the tube is not inserted into the lung.

- A "rush of air" (pneumothorax) or "rush of blood" (hemothorax) confirms pleural entry.

- The trocar technique is discouraged due to an increased risk of malposition and injury.

- Tube insertion and positioning

- The chest tube is inserted along the chest wall to a prespecified depth, ensuring that the sentinel port (the last hole on the tube that divides the radioopaque line) is completely within the chest wall (see Image. Surgically Placed Chest Tube).

- A straight tube should be directed anteriorly and toward the apex for pneumothorax to facilitate air evacuation.[9]

- For hemothorax or pleural effusion, a straight tube should be directed posteriorly and toward the apex, or a right-angled tube can be placed at the base of the lung and diaphragm for optimal drainage.[9]

- Aiming more toward the bed than the head during placement is associated with a lower risk of placing the tube in a lung fissure.[10]

- Securing and connecting the tube

- The tube must be sutured to the chest wall using 0 or 1-0 silk sutures to prevent accidental dislodgment or malposition.

- Consideration should be given to a secondary closure technique for proper wound healing after tube removal.

- The tube is connected to a drainage system and may be placed on suction (-20 cm H2O) if clinically indicated.

- Confirmation

- A chest x-ray (CXR) or bedside ultrasound should be obtained immediately after placement to confirm the correct positioning of the chest tube (see Image. Chest Tube on Plain Radiograph).

Chest tube care, monitoring, and removal are crucial for managing pleural space disorders, ensuring proper drainage, preventing complications, and promoting optimal recovery. The following is a comprehensive overview of these practices:

- Chest tube care

- Site management

- To reduce the risk of infection, the insertion site must be kept clean and dry, and a sterile dressing must be applied. The dressing should be changed regularly, and the site should be inspected for signs of infection, such as redness, swelling, or drainage.

- Tube patency

- Regular checks are needed to ensure the tube is not kinked or obstructed. If the chest tube becomes clogged, gentle milking or flushing with sterile saline (under physician guidance) may be used, though this should be done cautiously to avoid increasing pleural pressure.

- Drainage system:

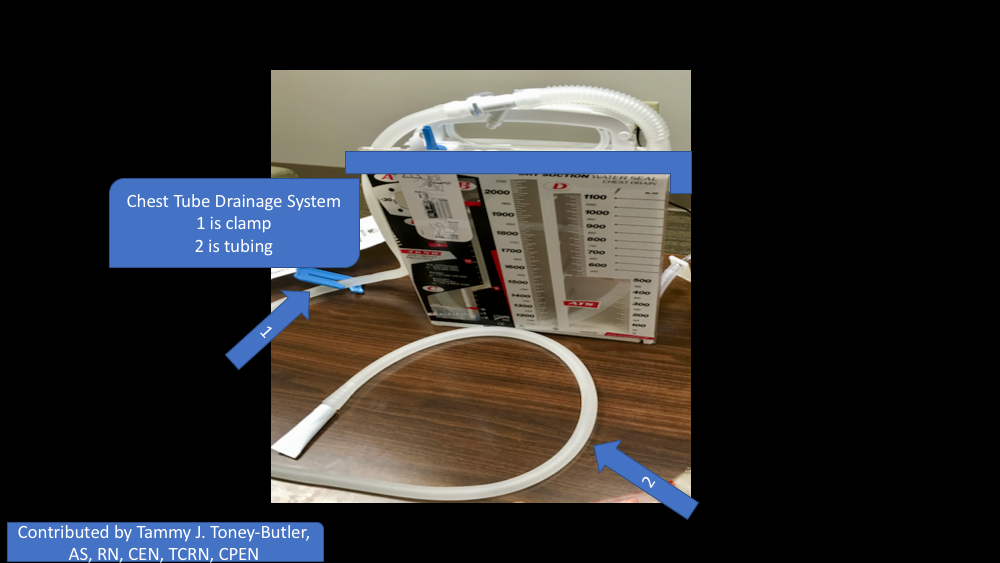

- The drainage system, often a water-seal or dry-seal device, should be positioned below the chest level to prevent fluid or air backflow (see Image. Chest Tube Drainage System). Clinicians should regularly monitor the drainage for fluid volume, color, or consistency changes. Sudden changes, such as increased drainage or a shift from serous to bloody fluid, may signal complications.

- Pain management

- Chest tubes can be uncomfortable, so appropriate pain management is important. Early mobilization and deep breathing exercises can also help prevent complications like atelectasis.

- Monitoring

- Postplacement CXR

- A CXR should be performed postplacement to assess lung reexpansion, the chest tube's position, and the sentinel port's location within the pleural cavity. If the sentinel port moves out of position, air can leak into the system, necessitating tube removal and potential replacement at a different site. For patients with pneumothorax, portable ultrasound is emerging as a useful tool for monitoring, although routine CXRs may not always be necessary.

- Tidaling

- Tidaling, the rise and fall of the water-seal chamber during respiration, indicates a patent chest tube influenced by negative pressure. The absence of tidaling may suggest tube occlusion. Milking or stripping the tube to resolve obstruction lacks strong evidence supporting its effectiveness.[11]

- Fluid drainage

- Clinicians should monitor the volume and type of fluid draining from the chest tube and note any significant changes that may require further intervention.

- Air leak assessment

- Bubbling in the water-seal chamber typically indicates ongoing air leakage. Most intrathoracic air leaks seal spontaneously, but persistent or large leaks (eg, from bronchopleural fistulas) may require surgical intervention. Bubbling can also indicate a leak in the circuit, which can be isolated by systematically evaluating the tube, starting with the insertion site. If necessary, clamping the tube in sections can help locate the leak.

- Interval CXRs

- Evidence supporting time-specific radiographic evaluation is limited, with some institutions choosing to follow patients clinically and not performing a routine radiographic evaluation.[12]

- Chest tube removal

- Indications and timing

- Chest tube removal should be considered when the underlying condition requiring drainage has resolved, and the risk of recurrent air or fluid accumulation is low. The primary indications for removal include full lung reexpansion without persistent pneumothorax, cessation of an air leak, minimal pleural fluid output, and the absence of ongoing infection or active bleeding. Data suggest that a period of observation without suction before removal may reduce recurrence, though there is no consensus on the optimal observation duration. Recent retrospective data have shown lower recurrence rates of the indication for chest tubes, in patients with an observation period off suction and before removal.[13]

- A chest tube is typically removed when drainage is <100 to 200 mL in 24 hours. However, enhanced recovery after surgery protocols suggest removal at <500 mL if no air leak, chylothorax, pus, or active bleeding is present.[14]

- The timing of removal depends on clinical progress and postoperative protocols. For pneumothorax, removal is generally considered when there has been no air leak for at least 24 hours and imaging confirms lung reexpansion. Removal of pleural effusions or hemothorax is appropriate when minimal drainage is nonpurulent. Recent evidence suggests that removal on the first postoperative day may improve outcomes, including reduced opioid use, pain, and length of hospital stay.[15] Regardless of the indication, chest tube removal should follow a sterile technique with an occlusive dressing to prevent air reentry, and patients should be monitored clinically and with imaging for recurrence.

- Procedure

- The procedure begins with patient preparation, including ensuring adequate pain control. This may involve premedication with analgesics or the use of a local anesthetic at the insertion site. The patient is positioned semiupright or supine, and the drainage system is temporarily disconnected.

- The removal should be timed with the patient's breathing to prevent air tracking into the pleural cavity and causing a recurrent pneumothorax. Avoid discontinuing the tube during inspiration, as this creates a pressure gradient that can draw air into the thoracic cavity. Instead, removal should be synchronized with exhalation, or the patient can be instructed to hold their breath or perform a Valsalva maneuver (such as blowing against their thumb as if inflating a balloon) to create positive intrathoracic pressure. However, it should be noted there is little data to support this practice.[16]

- Chest tube removal must follow a sterile technique to minimize infection risk. The securing suture is cut, and the tube is swiftly withdrawn in a controlled motion. An occlusive dressing, preferably petroleum-impregnated gauze, is immediately applied to the site to prevent air entry. Alternatively, a U-stitch placed during insertion can be tightened around the incision upon removal.

- Followup

- The role of routine CXRs after chest tube removal remains a topic of debate. Traditionally, a postremoval CXR has been standard practice to assess for residual or recurrent pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or other complications. However, emerging evidence suggests that routine CXRs may not be necessary in all cases, particularly in asymptomatic individuals. Study results indicate that selective imaging based on clinical assessment—such as monitoring for respiratory distress, decreased breath sounds, or hemodynamic instability—may be sufficient.

- Results from a recent study add valuable insight to this debate, advocating a shift toward clinically driven postoperative care. Evidence suggests that automatically ordering routine postremoval CXRs does not significantly alter patient management and may unnecessarily prolong the length of stay in patients undergoing elective thoracic surgery. Instead, reserving CXRs for symptomatic individuals can improve efficiency and support patient-centered healthcare delivery without compromising safety.[17] When performed, CXRs are typically obtained within a few hours of tube removal to detect complications early while minimizing unnecessary radiation exposure. If a clinically significant pneumothorax or fluid accumulation is observed, management options range from observation to repeat drainage depending on the patient's symptoms and overall clinical status.

- Emerging evidence points toward the benefit of portable ultrasound to monitor pneumothorax that requires continued chest tube placement.[18]

Complications

Chest tube placement is a common but potentially high-risk procedure that can lead to life-threatening iatrogenic injuries. The risk of complications begins at insertion, where adherence to best practices—such as the blunt dissection technique and placement within the "triangle of safety"—can mitigate injury. While most complications are preventable with proper technique and vigilance, they must be swiftly recognized and managed when they occur. The overall complication rate of chest tube thoracostomy is up to 37%, and it is reported that complications associated with tube thoracostomies increase the length of hospital stay and increase hospitalization costs.[19]

Iatrogenic Organ Injury

Injuries to intrathoracic and intraabdominal structures are among the most serious complications of tube thoracostomy. The following structures are at risk:

- Lungs

- Direct lung laceration or puncture can lead to pneumothorax, persistent air leaks, or parenchymal-subcutaneous fistulas.

- Diaphragm

- Minimal force is required to perforate the diaphragm, potentially leading to abdominal tube placement and intraabdominal organ injury.

- Esophagus

- Esophageal perforation can result in mediastinitis and sepsis.

- Heart

- Direct cardiac injury can lead to hemopericardium, tamponade, or fatal hemorrhage.

- Liver and spleen

- Subdiaphragmatic organ injuries are more common in lower rib fractures or improper trocar placement, potentially causing life-threatening hemorrhage.[1]

Vascular Injury and Bleeding

Inadvertent injury to major vessels can result in profound hemorrhage within the thoracic cavity. Vessel injury can involve:

- Great vessels (aorta, subclavian vessels)

- Lateral thoracic artery

- Thoracoacromial artery

- Intercostal vessels

- Internal thoracic vessels

- Pulmonary vessels [1]

Delayed recognition of vascular injury can result in hemothorax or retained clots, necessitating surgical intervention.

Tube Malposition

Tube malposition is the most common complication of tube thoracostomy. Literature has shown that inappropriate tube positioning occurs in up to 30% of patients.[10] Placement errors include:

- Extrapleural placement

- Chest tube positioned outside the pleural space

- Loculated cavity failure

- Incomplete drainage of an empyema or clotted hemothorax [1]

- Intraparenchymal placement

- Chest tube within lung tissue

- Fissural positioning

- Placement within a pleural fissure, leading to ineffective drainage

- Mediastinal or abdominal placement

- Tube migration into the pericardium, peritoneal cavity, or retroperitoneum

Radiographic confirmation with CXR or CT is essential to detect malpositioning.

Retained Collections and the Role of Intrapleural Therapy

Persistent hemothorax or loculated empyema that does not resolve with chest tube placement may require intrapleural thrombolytic therapy.[20] The most common regimen includes 5 mg of deoxyribonucleic acidase and 10 mg of tissue plasminogen activator in 50 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride, instilled through the chest tube and clamped for 60 minutes, followed by resumption of wall suction. This protocol, typically repeated twice daily for up to 6 doses, has been shown to reduce the need for surgical decortication but has not significantly impacted mortality rates.[21]

Infection and Increased Hospitalization Risks

Infections are a major concern after chest tube placement. While prophylactic antibiotics are recommended before the procedure, prolonged antimicrobial therapy has not been shown to reduce infection rates. Infections associated with chest tubes contribute to prolonged hospital stays and increased healthcare costs. Study results indicate that emergent chest tube placements, particularly in the emergency department setting, have higher complication rates due to suboptimal procedural conditions.[22]

Pain and Nerve Injury

Serious complications, although rare, such as injuries to lung parenchyma, heart, esophagus, and subcutaneous tube misplacements can occur, often leading to increased analgesic use due to insertion site pain.[22] Chest tube placement can result in intercostal nerve injury, leading to chronic pain and discomfort. An emerging approach to pain management is ultrasound-guided serratus anterior plane block, which has demonstrated efficacy in reducing opioid requirements and their associated adverse events.[23]

Rare and Unusual Complications

- Parenchymal-subcutaneous fistula

- This uncommon complication results from persistent air leaks and misplacement of the chest tube within the lung parenchyma.[24]

- Sinking skin flap syndrome

- This is a rare complication observed following decompressive craniectomy but also reported after chest tube placement in patients with ventriculopleural shunts.[25]

Preventive Strategies and Clinical Monitoring

Standardized procedural training and adherence to best practices are critical to minimize complications. Immediate postprocedural CXR is essential to confirm placement and detect early complications. Bedside ultrasound can provide additional confirmation, particularly in cases where tube position is uncertain. Ongoing clinical evaluation, including oscillation of the underwater seal drain, complete chest examination, and imaging as needed, is key to ensuring optimal patient outcomes.[22]

Clinical Significance

Chest tubes are vital for patients with pleural space pathology, such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, pleural effusions, and postsurgical drainage. Their primary function is to evacuate air, blood, or fluid from the pleural cavity to restore normal intrathoracic pressure, reexpand the lung, and prevent complications like atelectasis or further respiratory compromise. The clinical significance of chest tubes lies in their ability to prevent or treat conditions that can impair pulmonary ventilation and oxygenation. In pneumothorax (air in the pleural space), chest tubes help remove the trapped air, allowing the lung to reexpand and preventing the risk of tension pneumothorax, a life-threatening condition. Similarly, for hemothorax (blood in the pleural space), chest tubes aid in blood drainage and prevent the development of clotted masses that may impair lung function.

For patients with pleural effusions (accumulation of fluid in the pleural space), chest tubes can help remove the fluid, relieve symptoms like dyspnea, and improve oxygenation. They are also critical in postoperative care, particularly after thoracic surgery, to prevent fluid or air accumulation that could compromise lung expansion and recovery. Effective use of chest tubes requires careful monitoring for complications such as infection, tube dislodgement, obstruction, or injury to surrounding structures. Additionally, indications for chest tube placement should be well considered, as the decision to insert a tube is based on factors like the volume and type of fluid, the patient's hemodynamic status, and the underlying cause of pleural space involvement. In summary, chest tubes are essential in managing pleural space disorders. They are clinically relevant in stabilizing patients, improving respiratory function, and preventing life-threatening complications. However, their use necessitates ongoing monitoring and management to ensure optimal outcomes and avoid potential complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of chest tubes requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach to ensure patient safety and optimize outcomes. Clinicians must have technical proficiency in chest tube insertion, maintenance, and removal while recognizing potential complications early. Nurses play a vital role in monitoring drainage output, assessing for signs of infection or tube dysfunction, and providing patient education on mobility and breathing exercises to prevent complications. Pharmacists contribute by ensuring appropriate pain management strategies and, when indicated, antibiotic prophylaxis to reduce infection risk. Respiratory therapists assist in optimizing pulmonary function through incentive spirometry and breathing exercises, which are critical for recovery.

Clear and consistent interprofessional communication enhances patient safety and efficiency in chest tube management. Standardized protocols, such as checklists and bedside rounds, ensure all team members are aligned on treatment plans, tube status, and removal criteria. Coordination is significant in critical care and postoperative settings, where prompt recognition of complications like persistent air leaks or retained hemothorax can guide timely interventions. Implementing structured communication tools, such as SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation), can facilitate concise and effective handoffs between providers. By fostering a collaborative, patient-centered approach, healthcare teams can reduce complications, improve recovery times, and enhance patient experience.