Introduction

Located within the mediastinum between the third and sixth costal cartilages, the heart functions to supply tissues throughout the body with oxygenated blood. While the exact position is variable among patients, the heart tends to lie fairly horizontally, with the apex directed toward the patient’s left side.

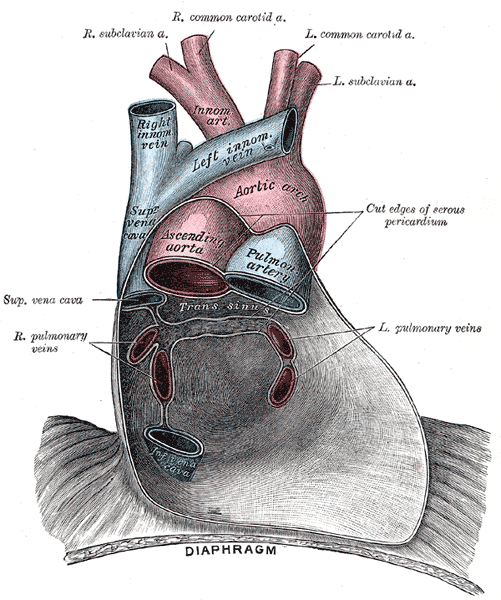

In order to maintain proper function, the heart and roots of the great vessels are encased within a double-walled fibrous sac termed the pericardium. On each side of the heart, the pericardium acts as the medial border of the pleural space. The most superficial layer, the fibrous pericardium, is robust and composed of many layers of connective tissue. The serous pericardium is divided into the parietal pericardium, which is directly fused with the fibrous pericardium, and the visceral pericardium, which adheres directly to the heart. In addition to the collagen and elastic fibers that make up the parietal pericardium, the visceral pericardium is also composed of mesothelial cells. The 2 layers are directly connected at the great vessels, where the pericardium reflects back on itself.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

The heart's ability to adequately pump blood throughout the body is directly dependent on its structure and pressure differences within its chambers. Simply put, blood flow through the heart can be visualized as two interwoven circuits. Deoxygenated blood returns to the right atrium, through the superior or inferior vena cava, and moves through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle of the heart during diastole. The tricuspid valve closes during the systolic phase, and blood is funneled through the pulmonic valve into the pulmonary circulation. Blood will become oxygenated and move into the left atrium, subsequently moving into the left ventricle through the mitral (bicuspid) valve. Due to the high pressure within the ventricle, oxygenated blood is ejected through the aortic valve and into the systemic circulation. [4]

The heart’s ability to perfuse tissues throughout the body is supported by the multiple physiological functions of the pericardium. The strong fibrous pericardium protects the heart by acting as a barrier against pathogens. Due to its non-compliant structure, the fibrous pericardium also serves to hinder severe dilation of the heart when intracardiac volume increases. The pericardium also functions to anchor cardiac structures through its many layers of connective tissue. By attaching to the sternum, diaphragm, and tunica adventitia, the fibrous pericardium limits the heart’s movement within the mediastinum. The pericardium plays a role by encasing pericardial fluid (usually 20 to 25 mL) within its two layers, which reduces friction during heartbeats by lubricating the surfaces involved. The fluid is rich in prostacyclin, which also helps to control coronary artery tone in the area. Compared to serum, the pericardial fluid has a lower osmolality, containing less protein and more albumin. It is secreted by mesothelial cells within the serosal layer.[5]

Embryology

Heart development begins within the fetus during the middle of the third week and begins to beat spontaneously by the end of the fourth week. The process of myocardiogenesis begins with the formation of endocardial tubes by lateral plate mesoderm. Body folding brings the endocardial tubes to the thorax, where the tubes fuse into a primary heart tube. Soon after, the myocardium, derived from the splanchnic mesoderm, covers the heart tube and the complex begins to loop.[6]

Once heart looping is complete at the end of week 4, separation of heart chambers begins. The formation of a septum primum begins to separate the atria while a muscular septum forms between the ventricles. Further separation occurs due to the growth of endocardial cushions, which develop on the atrioventricular canal. While vital for the creation of a four-chambered heart, the endocardial cushions also play a significant role in valve formation. By week 7, the formation of a foramen secundum and a foramen ovale occurs between the atria. In the following weeks, the coronary sinus is formed, and the semilunar and atrioventricular valves are completed.

The pericardium develops simultaneously with the development of the heart. As the heart tubes fuse and attach to anterior and posterior walls, the left and right intraembryonic coelomic cavities approach each other. Soon after, the cavities fuse and form the pericardial cavity, enveloping the heart tube within its dorsal wall.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Perfusion of the myocardium and epicardium is dependent on coronary arteries, which are normally embedded within epicardial fat. Left and right coronary arteries arise from their respective aortic sinuses, located just superior to the aortic valve. The left coronary artery moves for a small period within the coronary sulcus before dividing into the left anterior descending (LAD) and circumflex coronary arteries. The LAD runs anteroinferior, supplying the anterior two-thirds of the interventricular septum before commonly anastomosing with the posterior descending artery. The circumflex artery continues within the coronary sulcus toward the crux of the heart. Branches of these arteries adequately supply the left ventricle with blood and nutrients. The right coronary artery runs in the coronary sulcus toward the posterior section of the heart and is vital for perfusing the right ventricle through its marginal branches. On its path, it often perfuses the SA node. Near the crux of the heart, the AV nodal artery typically comes off the RCA. In over 70% of humans, the RCA continues and supplies the posterior one-third of the interventricular septum as the posterior descending artery.

Lymph within the heart drains from the subendocardial tissue within the atria and ventricles into an epicardial plexus. From here, the lymph runs in multiples vessels within the AV groove until combining and moving away from the heart in the mediastinal lymphatic plexus.

Blood supply to and from the pericardium is dependent on the pericardiophrenic branches of the internal thoracic vessels (formerly the internal mammary vessels). The pericardiophrenic artery runs between the pericardium and the pleura alongside the phrenic nerve.

Lymphatic drainage of the visceral pericardium utilizes the tracheal and bronchial lymph chain while the parietal pericardium drains similarly to the sternum and diaphragm.

Nerves

Cardiac function is dependent on properly timed contractions of the atria and ventricles. In a healthy heart, the impulse originates within the sinoatrial node (SA node), which is a mass of muscle fibers in the right atrium wall. Conduction moves to the atrioventricular (AV) node within an inferior section of the interatrial septum. Here, the impulse is momentarily delayed, which allows for filling of the ventricles, before traveling through the bundle of His in the interventricular septum. The bundle of His bifurcates into right and left bundle branches as it moves inferiorly. The impulse is then distributed through the Purkinje fibers (subendocardial branches), which transmit the signal to papillary muscles and the ventricular wall. Coordinated contraction of the ventricles begins at the apex and moves toward the base.

The rate (chronotropic) and force (inotropy) of cardiac contractions are regulated through sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation. Cell bodies for sympathetic innervation are located within the first 5 thoracic levels of the spinal cord while parasympathetic innervation works through branches of the vagus nerve (CN X).

The fibrous pericardium and serous pericardium are innervated by the phrenic nerve, which is derived primarily from cervical nerve 4 but also has contributions from the 3 and 5. Due to its origin, pericarditis and other cardiac complications can cause referred pain to the shoulder. The serous pericardium has branches of innervation from the vagus nerve via the esophageal plexus. The pericardium has an extensive set of mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors that are responsible for certain reflexes. The Bezold-Jarisch reflex refers to a triad of bradycardia, hypotension, and apnea that occurs due to receptors in this area.

Muscles

Moving superficially, the heart wall can be divided into the endocardium, myocardium, and epicardium. The endocardium is a thin layer of supporting connective tissue and smooth muscle fibers, which line the heart chambers and valves. Connective tissue builds up within the subendocardial layer, which attaches to the myocardium and contains branches of the heart’s conduction system. The myocardium is the thickest of the three layers, particularly within the left ventricle, and is responsible for the ejection of blood during contractions. The epicardium (visceral pericardium) is responsible for the production of pericardial fluid and the protection of the other heart layers.

Physiologic Variants

Dextrocardia refers to the congenital condition where the apex of the heart is directed toward the right side of the chest. The defect is often attributed to Kartagener syndrome (primary ciliary dyskinesia).

A patent foramen ovale occurs if the septum primum and septum secundum fail to fuse during embryogenesis. This can lead to paradoxical emboli that enter systemic circulation instead of the lungs.

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is a congenital heart defect due to the anterior deviation of the aorticopulmonary septum. The malalignment leads to pulmonary stenosis, an overriding aorta, a ventricular septal defect, and right ventricular hypertrophy.

Ventricular septal defects are the most common congenital cardiac anomaly. They often occur within the membranous portion of the ventricular septum and can lead to a left-to-right shunt within the newborn.

While the pericardium serves many physiological roles, its presence is not a necessity. Congenital absence of the pericardium or its surgical removal (pericardiectomy) does not tend to cause symptoms in patients.

Defects of the pericardium are infrequent (approximately 1 in 10,000 patients) and have a left side predominance (70%). They can occasionally compress cardiac structures, such as coronary arteries or the left atrial appendage.

Surgical Considerations

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is a procedure to restore cardiac tissue perfusion after a coronary artery becomes occluded. Two common approaches including rerouting the left internal thoracic artery to the LAD or using the great saphenous vein from the patient’s leg.

Pericardiocentesis is a medical procedure where the fluid is aspirated from the pericardial cavity. Typically, the needle is inserted just left of the xiphoid process and inferior to the left costal margin. Echocardiography is often utilized to prevent puncturing the heart.

Due to their location on each side of the pericardium, phrenic nerves must be identified during thoracic surgeries. Damage can lead to paralysis of the diaphragm.

At their lines of reflection, the visceral and parietal pericardium layers create two sinuses. The transverse pericardial sinus, located posterior to the ascending aorta and anterior to the superior vena cava, is an important landmark to identify structures during CABG procedures. A second pericardial sinus, the oblique sinus, is located posterior to the left atrium and allows for distension of the chamber.

Clinical Significance

Pericardial effusion refers to abnormal levels of fluid within the pericardial space. This is often attributed to a decrease in fluid resorption, which can occur with a lymphatic obstruction or venous hypertension. In acute cases, the sudden increase of volume can lead to heart dysfunction if the pressure increases enough. However, slow accumulation of fluid can cause the pericardium to stretch, which allows the cavity to withstand higher pressures. While a range of clinical features exists, effusions commonly present with chest pain or dyspnea.[7][8]

Pericarditis refers to inflammation of the pericardium, which often presents with chest pain and fever. Typically, the pain worsens with inspiration or coughing and is alleviated by leaning forward or sitting. On auscultation, a friction rub is often present. Acute pericarditis can be attributed to both infectious and non-infectious causes. While often idiopathic, many cases are thought to be viral with echovirus and coxsackievirus being the most common. Noninfectious causes of pericarditis include neoplasms and damage caused by myocardial infarction. Electrocardiograms in patients with pericarditis typically show ST-segment elevation in all leads besides aVR and V1.

Dressler syndrome is a form of pericarditis, believed to be an autoimmune reaction to certain myocardial antigens, that occurs at least 2 to 3 weeks after myocardial infarction.

Constrictive pericarditis refers to fibrosis and thickening of the pericardium. The subsequent loss of compliance decreases the heart’s ability to pump blood adequately. The majority of cases of constrictive pericarditis are considered idiopathic. In addition to reduced cardiac output and elevated venous pressures, Kussmaul’s sign may also be observed. This refers to a paradoxical increase in jugular venous distension during inspiration.

Cardiac tamponade occurs when an increase in pressure, due to causes such as hemopericardium or pericarditis, compresses the heart and restricts adequate cardiac output. By decreasing compliance, normal venous return to the right atrium is hindered. Acute cardiac tamponade can present with Beck’s Triad, which includes hypotension, jugular venous distension, and muffled heart sounds on auscultation. Pulsus paradoxus, an exaggerated decrease in systolic blood pressure during inspiration, is also often seen.[9][10]