Introduction

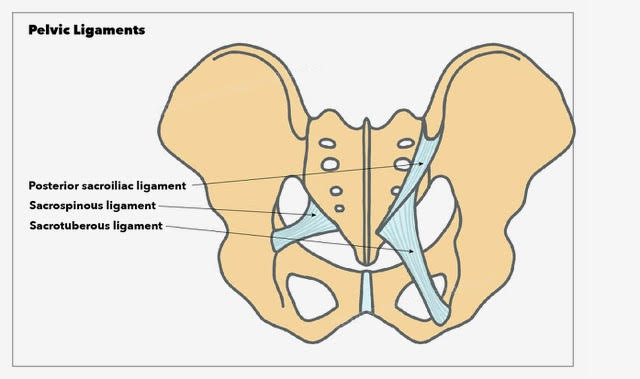

The pelvis's bony integrity is supported by various ligaments that lend crucial flexible strength to the pelvic cavity and support some of the internal pelvic structures.[1] The principal ligaments are sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, and iliolumbar, and in the female pelvis, there are further ligaments to support the ovaries and uterus (see Image. Pelvic Ligaments).[2] Trauma or stretching of these ligaments can result in pain syndromes, causing a significant impact on quality of life if not recognized and treated appropriately.[3] Furthermore, pelvic floor dysfunction, which describes wider pathology involving the entire pelvic floor musculature and ligaments, can harm urinary, bowel, and sexual function.[4][5]

Structure and Function

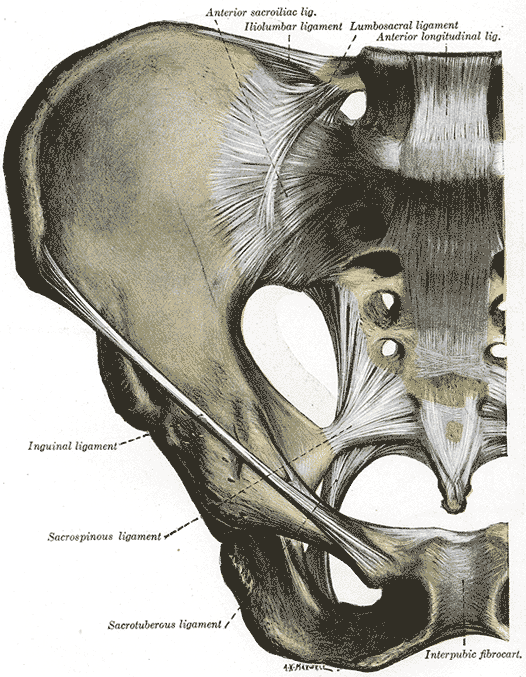

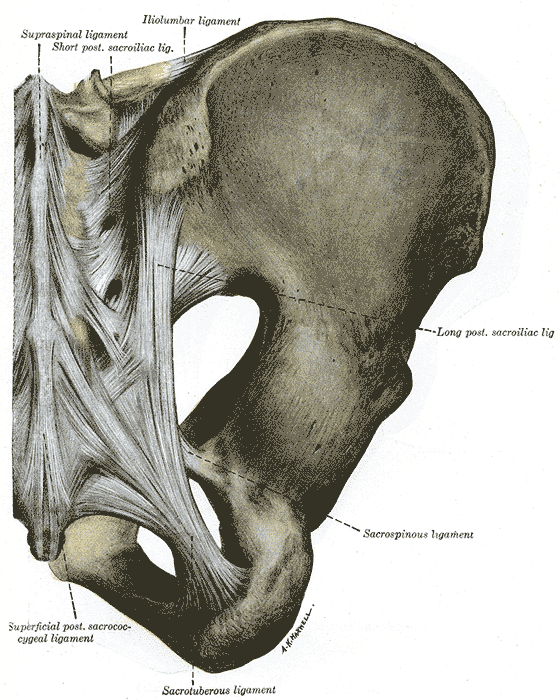

The key ligaments of the pelvis present in both sexes are the sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, and iliolumbar ligaments. Further ligaments include the anterior sacroiliac, anterior sacrococcygeal, posterior sacroiliac, posterior sacrococcygeal, and pectineal ligaments. See Images: Anterior Articulations, Pelvis, Posterior articulations, Pelvis. Further, specific female pelvic ligaments are the broad ligaments and ligaments of the ovaries and uterus.

The Sacrotuberous Ligament

The sacrotuberous ligament is a fan-shaped fibrous band of connective tissue with great strength, providing stability to the posterior pelvis.[6] Its wider superior origin runs from the transverse tubercles of the sacrum below the level of the sacroiliac joint, the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines, and the upper coccyx, downwards to attach to the tuberosity of the ischial tuberosity.[7] The average length of the sacrotuberous ligament from cadaveric dissections is 70 mm in women and 64 mm in men.[8] The sacrotuberous ligament is blended with the posterior sacroiliac ligament, a continuation of the superficial fibers of the sacroiliac ligament, which attaches the sacrum firmly to the ilium.

The Sacrospinous Ligament

The Sacrospinous ligament is a triangular band of connective tissue that lies on the pelvic aspect of the sacrotuberous ligament. It has a broad base with origins at the lower sacrum and upper coccyx. It travels laterally from its base, narrowing as it does so, to attach to the spine of the ischium and has an average length of 46 mm in women and 38 mm in men.[7][8] The sacrospinous ligament divides the greater sciatic notch to the greater sciatic foramen and the lesser sciatic foramen, through with pass several important neurovascular structures critical to the lower limb and genital function, including the gluteal, pudendal, and sciatic nerves and the gluteal and pudendal vessels.[9][10]

The Iliolumbar Ligament

The iliolumbar ligament is composed of thick and strong fibrous bands of connective tissue originating from the tip of the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra. It extends laterally as a superior and inferior band, resembling a V-shape. The superior band inserts at the iliac crest, and the inferior band blends with the front of the anterior sacroiliac ligament on the pelvic surface of the ileum.[11] This ligament stabilizes and strengthens the lumbosacral joint, restricting the rotational movement at the lumbosacral joint.

Sacroiliac Ligaments

The sacroiliac joint complex is reinforced by various ligaments that provide structural support to this important joint within the pelvis. The interosseous sacroiliac ligament provides the largest and most robust sacroiliac joint support in both females and males. It attaches at deep pits on the lateral mass of the posterior surface of the sacrum, extending to the ilium in a series of short and very strong fibers. As mentioned above, its anterosuperior surface blends with the iliolumbar ligament. Furthermore, the most superficial fibers of the posterior aspect of the interosseous sacroiliac ligament form the posterior sacroiliac ligament.[12] The anterior sacroiliac ligament is a band of connective tissue that connects the anterior surface of the lateral part of the sacrum to the margin of the auricular surface of the ilium.

Sacrococcygeal Ligaments

The sacrococcygeal joint is reinforced with anterior, posterior, and lateral ligaments. The anterior sacrococcygeal ligament unifies the anteriormost aspect of the respective bone bones. Posteriorly, 2 posterior sacrococcygeal ligaments perform a similar function in the dorsal aspect of the joint. Finally, 2 lateral sacrococcygeal ligaments run from the coccygeal transverse processes inferiorly to the angle of the sacrum.[13]

Ligaments of the Pubic Symphysis

The pubic symphysis is a midline cartilaginous joint uniting the 2 pubic bones. Small ligamentous supports to this joint are present in the superior pubic ligament and the arcuate pubic ligament inferiorly. The strength and contribution to joint stability provided by these ligaments are controversial. However, it is accepted that the arcuate pubic ligament is stronger than its superior counterpart.[14]

Female Pelvic Ligaments

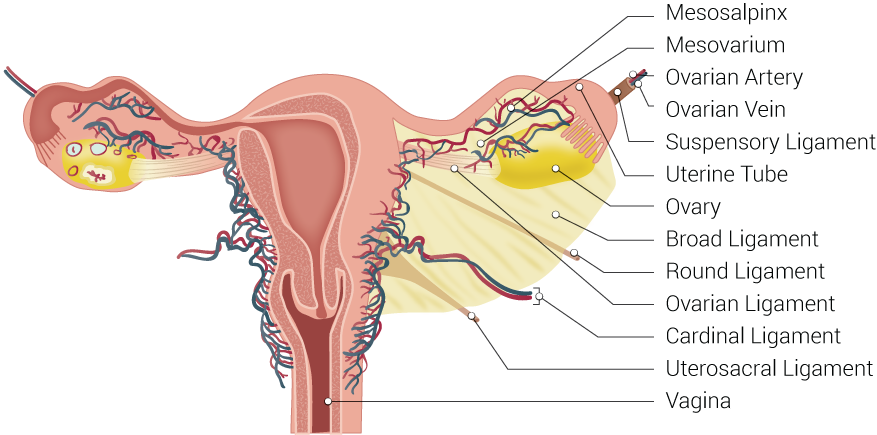

The broad ligament is a sheet of pelvic peritoneum extending bilaterally from the lateral pelvic sidewalls to the uterus in the midline.[15] The broad ligament folds over the fallopian tubes and ovaries and covers them anteriorly and posteriorly. It is subdivided into the mesovarium, mesosalpinx, and mesometrium. See Image. Uterine Tubal Anatomy and Ligaments. The mesovarium is the part of the broad ligament related to the ovaries. This posterior sheet of broad ligament extends to the hilum of the ovary and contains the neurovascular tissue of the ovary, here as the suspensory ligament of the ovary. The peritoneal fold of the broad ligament does not cover the surface of the ovary, but rather, the anterior border of the ovary is attached to the broad ligament. The mesosalpinx is the part of the broad ligament related to the fallopian tube. Here, the broad ligament folds over and encloses the fallopian tube. The mesometrium is the part of the broad ligament related to the uterus. From the uterus, the broad ligaments fan out laterally while covering the external iliac vessels. The mesometrium is the largest section of the broad ligament.

Ligaments Related to the Ovary

Two ligaments are attached to the ovary, namely the (median) ovarian ligament and the suspensory ligament of the ovary. The (median) ovarian ligament is a fibrous band of connective tissue attached to the ovary inferiorly. It extends medially to the uterus's fundus below the fallopian tube's attachment.[16] The suspensory ligament of the ovary is composed of the peritoneal fold extending from the ovary to the lateral pelvic wall. It is not a true ligament. It blends with the broad ligament fold and contains the ovarian artery, ovarian vein, ovarian nerve plexus, and lymphatic vessels.

Ligaments Related to Uterus

Four ligaments are attached to the uterus: the round ligament, the cardinal ligament, the pubocervical ligament, and the uterosacral ligament. The round ligament of the uterus is attached to the cornu of the uterus.[17] It travels through the inguinal canal and blends with labia majora and mons pubis. The cardinal ligament, the transverse cervical ligament, is attached from the lateral aspect of the cervix to the respective pelvic wall. It forms the inferior border of the broad ligament and houses the uterine artery and uterine veins. The pubocervical ligament is attached to the cervix and extends to the posterior surface of the pubic symphysis.[18] The uterosacral ligaments provide, along with the cardinal ligaments, the key support for the uterus within the pelvis and attach from the cervix below the peritoneum backward to the anterior aspect of the sacrum.[19] Other ligaments of the pelvis include the pubovesical ligaments, puboprostatic ligaments, sacrogenital, urachus ligaments, and suspensory ligaments of the penis in males.

Embryology

Male and female gonads develop from primitive germ cells from the mesothelium of the posterior abdominal wall. Gonadal development begins in the fifth fetal week. The broad ligaments are formed after the fusion of both müllerian ducts.[20] The müllerian ducts eventually canalize and become the uterus, bilateral fallopian tubes, and cervix uteri. The round ligament and medial ovarian ligaments develop from the embryonic gubernaculum. Agenesis, aplasia, or failure of fusion of the müllerian ducts can lead to primary amenorrhea and associated genitourinary abnormalities. Some examples of genitourinary abnormalities are, but are not limited to, ectopic or absent ureters, unilateral renal agenesis, or bicornuate uterus. The connective tissue of the pelvis – including the ligaments – develops initially from loose undifferentiated mesenchymal tissue in the 9-12 week-old fetus before forming dense connective tissue between 13 to 20 weeks.[21]

Clinical Significance

Pregnancy-related Pelvic Ligament Dysfunction

Pelvic girdle pain is common in the third trimester of pregnancy, as the gravid uterus exerts more axial load on the pelvic structures. This leads to pelvic ligamentous stretch and pain and is a common cause of significant pain and discomfort in the later stages of pregnancy.[22] General recommendations for managing pelvic girdle pain include pelvic support garments, simple analgesia (eg, paracetamol), and guided physiotherapy exercises. Prolonged or difficult vaginal delivery can cause significant trauma to the pelvic structures. Post-natal pain and pelvic organ prolapse may occur - specifically cystocele, urethrocele, cystourethrocele, enterocele, rectocele, or prolapse of the uterus into the vagina. In asymptomatic patients, conservative management is recommended, which includes vaginal pessaries and Kegel exercises.[23] In symptomatic patients, if conservative management fails, surgery is performed to correct defects and relieve these symptoms. Sacrospinous ligament fixation may be used to anchor the vaginal vault to aid in preventing vaginal vault prolapse.[24][25][26]

Pudendal Nerve Entrapment

The pudendal vessels and nerves pass behind the sacrospinous ligament. The pudendal nerve may get trapped between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments.[27] This may lead to perineal pain, genital numbness, and incontinence (both urinary and fecal). The main symptom of pudendal nerve entrapment is severe pain while sitting.[28] Because of this, pudendal nerve entrapment is called bicyclist syndrome. If needed, special imaging studies, such as an MRI of the pudendal nerves, may be ordered. Temporary relief may be obtained via an ultrasound-guided pudendal nerve block. In those without response following this intervention, surgery may help relieve symptoms by decompression. A randomized control trial demonstrated that surgical decompression is efficacious and safe in patients with pudendal nerve entrapment unresponsive to conservative measures with analgesia and nerve blocks.[29] The trial found that among 16 patients, 71% had experienced improved symptoms following surgical decompression, which was associated with no surgical complications, and the improvement in symptoms persisted at 4-year follow-up in three-quarters of patients.

Ligamentous Dysfunction in Lower Back Pain

The most common causes of lower back pain are muscular-ligamentous sprains and strains, mainly in the lumbosacral region.[30] Injury and damage may happen to these lumbosacral ligaments because of falls, violent accidents, and other trauma to the region. Lumbosacral sprains usually occur after a forceful or rapid movement, which may cause a tear in the lumbosacral ligaments.[31] Too much movement (hypermobility or instability) or too little movement (hypomobility or fixation) may cause or aggravate sacroiliac joint pain secondary to strain or tear of the associated ligaments.[32] Biophysical modeling demonstrates the importance of these ligaments in the support and motion of the lower limbs. When sacrotuberous and sacroiliac tears are modeled, the result is contralateral pelvic instability, which likely correlates with functional disability and pain in vivo following ligamentous injury.[6] Rest from weight-bearing activities is advised in all cases of injury. Ice and cold compressions are recommended to reduce inflammation and pain. Local massage, anti-inflammatory medications, and physiotherapy may be helpful.[33] Despite conservative management, ongoing symptoms require specialized input from surgical, gynecological, urological, or neurosurgical teams as appropriate.