Introduction

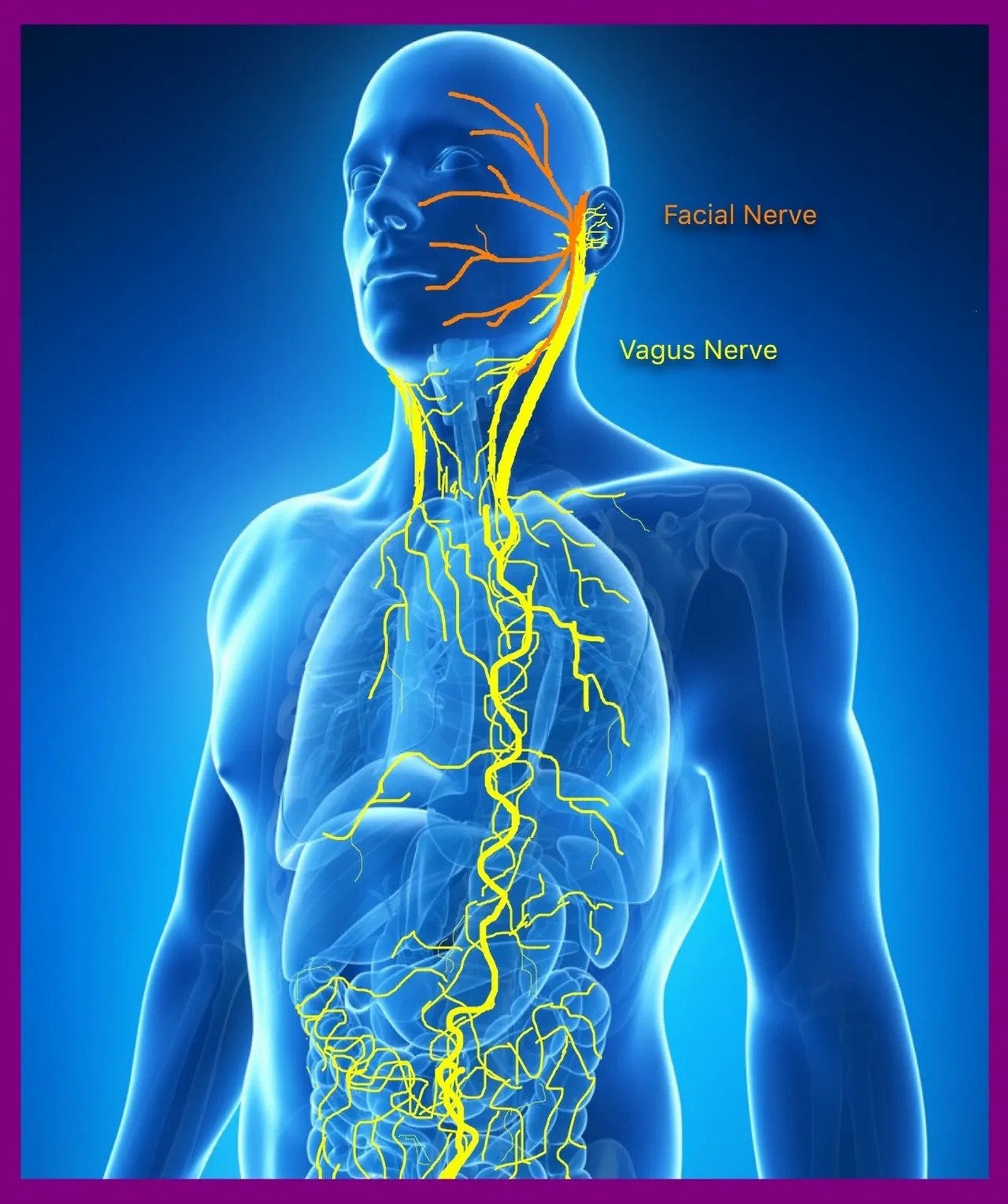

The vagus nerve, or CN X, the tenth cranial nerve, is a nerve that serves numerous important functions. While the majority of the fascicles function in parasympathetic activity, the vagus nerve also contains somatic sensory, visceral sensory, and branchial motor fibers. In Latin, vagus means, "wandering, straying." The vagus nerve is thus named because it follows a complex course throughout the body to innervate several organs; fibers originate from the dorsal motor nucleus and nucleus ambiguus in the ventral medulla oblongata of the brainstem, with terminal branches reaching the splenic flexure of the colon. A critical division during the nerve's course from rostral to caudal occurs as it enters the abdominal cavity: it splits into an anterior trunk and a posterior trunk. The structural and functional properties of the anterior trunk, along with its relevant surgical and clinical considerations, will be examined in this article.[1][2][3]

Structure and Function

Four nuclei located at varying levels of the medulla house cell bodies of the vagus nerve: the dorsal nucleus, which serves parasympathetic function to the heart, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract via general visceral efferent fibers; the nucleus ambiguus, which is responsible for special visceral efferent activity and houses cell bodies not only for the vagus nerve, but also for the ninth and eleventh cranial nerves; the solitary nucleus, which receives general visceral afferent innervation from the carotid body and sinus via cranial nerve nine, general visceral afferent information from the aortic bodies and sinoatrial node of the heart, as well as special visceral afferent information (i.e., taste) from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.[1]

The vagus nerve proper is formed from multiple rootlets as it emerges from the cranial vault through the jugular foramen. After its emergence, two sensory ganglia form: these are the superior ganglion and inferior ganglion. These ganglia house the cell bodies of the sensory neurons responsible for the vagus nerve's afferent activity.[4]

As the vagus nerve enters the abdominal cavity through the esophageal hiatus, it splits into an anterior trunk and a posterior trunk. The anterior trunk is mainly responsible for gastrointestinal parasympathetic innervation to the lesser curvature of the stomach, the pylorus, the biliary apparatus, and the gallbladder.

Embryology

The vagus nerve's embryological origins can be traced back to special visceral, as well as general visceral afferent and efferent nuclei, that arise from the myelencephalon.

From the sixth week, it is possible to distinguish the cranial nerves, among which is the tenth cranial nerve. There is a close relationship between the development of the vagus nerve and the enteric system. The embryological leaflet involved is the ectoderm.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

An explicit artery, the vagal artery, provides the primary blood supply to the vagus nerve. This artery tracks on the anterior surface of the nerve and is at considerable risk during several surgical procedures.[5]

The bronchoesophageal artery supplies the vagus nerve with a branch in the mediastinum, to the left in the subaortic region. Additionally, in the mediastinal region, the vagus nerve can be vascularized by arteries from the aortic arch, from a first intercostal artery, and inferior thyroid artery.

The veins that affect the vagus nerve at the level of the mediastinum are the internal thoracic vein from the anterior area and the thoracic intercostal veins from the posterior area.

Nerves

Important branches of the vagus nerve include: the superior laryngeal nerve, which has two branches, the internal laryngeal nerve (at risk with regional lymphadenopathy or trauma), and the external laryngeal nerve (at risk during superior thyroid artery ligation); and the recurrent laryngeal nerve (at risk as it wraps around the aortic arch on the left-handed side; therefore, aortic arch pathology, such as an aneurysm of any kind, endangers this nerve. It can also be damaged during patent ductus arteriosus repair, as well as perioperatively during ligation of the nearby inferior thyroid artery.[6][7]

The vagus nerve splits into two trunks: the anterior and posterior vagal trunks. The anterior trunk, which receives significant contributions from the left vagus nerve more so than the right, branches into: a hepatic branch, which supplies the liver, gallbladder, and biliary apparatus; a celiac branch, which contributes parasympathetic fibers to the celiac plexus; and numerous anterior gastric branches, the most medial of which courses along the lesser curvature of the stomach. The pylorus and proximal duodenum receive innervation from the anterior and posterior nerves of Latarjet, which are both branches off of the anterior vagal trunk.[8]

Muscles

Several muscles receive innervation from the vagus nerve: the middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscles, which are responsible for passage of food boluses; the palatoglossus, which elevates the posterior portion of the tongue on swallowing; and the laryngeal muscles, the aryepiglottic, thyroarytenoid, arytenoid, lateral and posterior cricoarytenoid, which are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve. The entire length of the esophagus is also the recipient of motor innervation.[9]

The vagus nerve innervates the crural area of the diaphragm (where the esophagus passes or esophageal hiatus).

The tenth cranial nerve innervates the suspensory muscle of the duodenum or musculus suspensorius duodeni.

Physiologic Variants

In a study of 50 dissections, Jackson et al. discussed anatomical variants of the vagus nerve in the area of the distal esophagus and stomach. From their specimens, they found that the left vagus nerve contributed more fibers to the anterior vagal trunk than did the right, albeit the right vagus did contribute more branches overall.

In their analysis of the branching pattern of the anterior vagal trunk, they found four distinct types of patterns: in one pattern (type A, 33 specimens), the anterior trunk became a single trunk above the diaphragm, and subsequently passed through the diaphragm; in another variation (type B, 14 specimens), the anterior vagal trunk was also formed above the diaphragm, as in the previous variation, but split into two distinct branches just before encountering the diaphragm; a third type (type C, two specimens), in which a single trunk did not form until the trunks reached the diaphragm; and a final type (type D, one specimen), in which the researchers noted no single trunks above the diaphragm.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Fundoplication

The anterior vagal trunk and its branches are at considerable risk during surgeries involving the distal esophagus, stomach, proximal duodenum, biliary tract, and gallbladder. One such surgery is the fundoplication, often indicated in good surgical candidates who suffer from gastroesophageal reflux disease refractory to medical therapy.

Investigators have experimented with severing the hepatic branch of the anterior vagal trunk while performing a fundoplication to determine the post-operative effects on the function of the gallbladder. This branch coming off the anterior vagal trunk innervates the liver, biliary apparatus, and provides motor innervation to the gallbladder (i.e., gallbladder contractile function).[10] Purdy et al. studied this because laparoscopic fundoplications were considered technically easier with the cutting of this branch, but limited data about postoperative effects on general gallbladder motor function was available. They cite a Finnish surgeon, Dr. M. Paakkonen, who altered the technique of handling the hepatic branch during fundoplications in 2001. Patients who had fundoplications done before and after this date received symptom questionnaires; from these patients, 19 were investigated further in two distinct groups. In particular, the volume of the gallbladder and gallbladder ejection fraction after a fatty meal (measured by ultrasound) were of importance, as well as the serum concentrations of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and amylase. The investigators noted no significant difference in symptoms or PRN use of medication between the two groups.[10][11]

A common and unfortunate post-operative side effect of this procedure is flatulence. A report published in September of 2019 by Cockbain et al. investigated the incidence of post-operative flatulence in patients who underwent primary laparoscopic fundoplication. The study entitled Flatulence After Anti-reflux Treatment (FAART) identified select patients who had this procedure done for symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease refractory to medical therapy from 1999 and 2009, and scrutinized incidence of flatulence at follow-up. At a follow-up of 8 to 15 years post-op, 85% of patients reported excessive flatulence. The study also concluded that flatulence was indeed worse in patients who had a total fundoplication in contrast to those who underwent a partial fundoplication. Although the incidence in this population was high, the overall impact on daily life was small.[12]

Clinical Significance

Gastroparesis

A condition defined by delayed gastric emptying, gastroparesis presents in patients with nausea, vomiting, bloating, flatulence, early satiety, and loss of appetite. The mechanism of the delayed gastric emptying seen here is thought to be mediated by a disturbance in the strength and timing of baseline gastric contractility. While other causes of delayed gastric emptying may be related to a mechanical obstruction, gastroparesis is usually either idiopathic, a feared complication of diabetes mellitus due to autonomic neuropathy or even a result of iatrogenic damage during abdominal surgery. The first-line pharmacological agent used for gastroparesis is metoclopramide, a dopamine receptor antagonist that has prokinetic properties. Second-line agents include erythromycin and cisapride.[13]

A well-established cause of gastroparesis in the diabetic patient population is an autonomic neuropathy of the vagus nerve. When the parasympathetic function to the proximal foregut is compromised, in particular, gastric fundic and antral motor activity[14], gastric contents cannot advance at an appreciable rate, resulting in the typical symptoms patients experience. Patients with diabetes and poor glycemic control can experience neuropathies of a variety of nerves, as well as autonomic neuropathies, either cardiovascular or gastrointestinal, which can prove to be especially worrisome.

A study published in 2005 by Moldovan et al. investigated diabetic gastroparesis in 36 patients via ultrasonographic techniques. Thirteen patients with diabetes mellitus type 1 were in the study sample (HbA1c = 8.1 +/- 1.4), and 23 with diabetes mellitus type 2 comprised the rest of the subjects (HbA1c = 9.7 +/- 1.2). Focusing specifically on autonomic causes, the investigators further divided patients up into groups based on their type of diabetes, and whether they were found to have normal gastric emptying or delayed gastric emptying. In the group of type 1 diabetics, they observed that 50% with normal gastric emptying tested abnormally for parasympathetic neuropathy; in those with delayed gastric emptying, 71.5% tested positive for parasympathetic abnormalities. In the group comprised of type 2 diabetics, the following results were achieved: 46.5% with normal gastric emptying displayed aberrant parasympathetic function, and 75% with delayed gastric emptying revealed parasympathetic abnormalities.[15]