Introduction

Head and neck anatomy can be complicated as a result of the vast number of minute anatomical structures in the spatially limited anatomic region. Clinically, there are a vast number of structures that require special attention, and failure to do so can result in fatal consequences.

The neck is divided into several regions, triangles, and zones to organize the complex anatomy of this area. The two primary neck regions are the anterior cervical and posterior cervical triangles, which are found deep to the skin and subcutaneous tissue and contain several muscles, vasculature, and nerves.

The objective of this article is to describe the anatomy of the anterior cervical region and the anterior triangle of the neck, as well as any notable clinical or surgical considerations.

Structure and Function

Structure of the Anterior Cervical Region

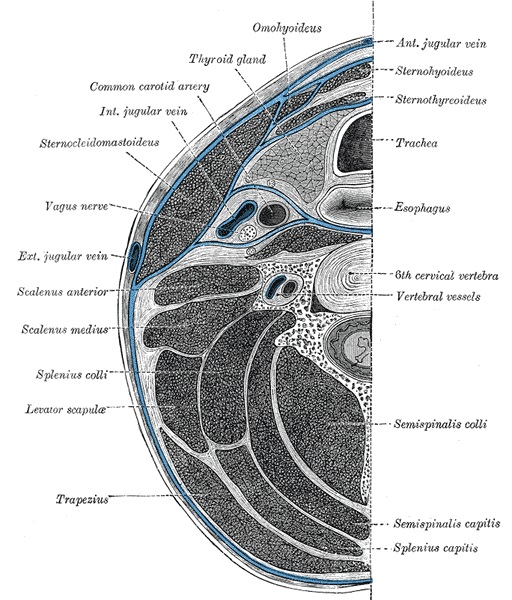

The anterior cervical region or triangle can be topographically located at the anterior portion of the neck. It spans seven levels of cervical vertebrae (C1-7). The anterior triangle is a region bounded superiorly by the inferior border of the mandible, laterally by the anterior median of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, and inferiorly by the jugular and clavicular notch of the manubrium.

Immediately inferior to the skin is the superficial investing layer of the fascia, followed by the platysma muscle, which is the most superficial musculature in this anterior triangle. This large, flat muscle arises from the pectoralis major muscle fascia and extends superiorly to insert into the mandibular base. Functions of this muscle include depression of the jaw bone and grimacing maneuvers of the face.

The anterior triangle of the neck can further subdivide into four smaller regions, which include the submental or digastric triangle, submandibular triangle, carotid triangle, and muscular triangle.

Submental Triangle

The craniocaudal border of the submental region is the chin and hyoid bone, bilateral boundaries are the anterior belly of the digastric muscle. The mylohyoid muscle composes the floor of this region, and it contains the submental lymph nodes, an important site of metastasis.[1]

Submandibular Triangle

Immediately lateral on either side of the submental triangle is the submandibular or digastric triangle. The superior border of this triangle is the lateral margin of the mandible on either side, while the anteroposterior boundaries are the anterior and posterior bellies of the digastric muscle. Significant contents of this triangle include the submandibular gland, submandibular lymph nodes, hypoglossal nerve (CN XII), facial artery, and facial vein. This region is also home to the glossopharyngeal and lingual nerves, the former being involved in stretch signaling for the carotid baroreceptor reflex.[2]

Carotid (Superior Carotid) Triangle

Inferolateral to the submandibular triangles are the carotid triangles, which contain vital vasculature for the entire body. The omohyoid muscle is the anterior border of this triangle, and the posterior belly of the digastric makes up the superior border. The anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid makes up the posterior of this triangle. The contents of this triangle include the internal and external carotid bifurcations, the carotid body, the hypoglossal (CN XII) nerves, and vagus (CN X) nerves. It also includes the internal jugular vein, as well.[3]

Muscular (Inferior Carotid) Triangle

The fourth and final triangle is known as the muscular triangle, which extends in the midsternal plane laterally to the omohyoid (superior belly) and sternocleidomastoid (anterior belly). It contains the sternothyroid and sternohyoid muscles, as well as the thyroid and parathyroid glands. The sternohyoid muscle depresses the hyoid bone and lies superficial to the sternothyroid muscle. Both muscles overlie other neuro-vasculature, including the common carotid artery, vagus nerve, internal jugular vein, and anatomic structures like the esophagus and trachea.[4]

Embryology

Anatomical structures of the head and neck derive from the pharyngeal apparatus, which in the human embryo contains six distinct arches craniocaudally.

Any single arch of the apparatus contains a central mesoderm and neural crest cells, which form the cartilage, fascia, muscles, and nerves of that region. These arches are further lined to form branchial clefts composed of ectodermal tissue, and on the deep side, endodermal branchial pouches comprise the entirety of the arch.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

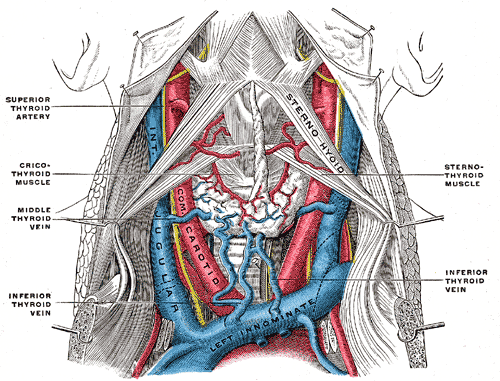

Blood vessels of the Anterior Cervical Region

The deep midline viscera of this region are the larynx and thyroid gland. The two lateral stalks of neuro-vasculature largely supply these two areas.[5]

Below the subcutaneous platysma and investing layer of the deep cervical fascia in the middle reveals a vast network of blood vessels that supply not only this area but the entire body.

Of note, this area contains the carotid sheath, which is a thick fascial layer emerging posterior from the sternocleidomastoid. It then ascends the length of the carotid triangle, and its contents pass behind the posterior belly of the digastric and continue into the lateral cervical region of the neck. This sheath encases the following vessels: common carotid artery (a superior portion), both proximal portions of the internal and external carotid arteries, the internal jugular vein and the vagus nerve.

The common carotid artery can be found anteromedial to the internal jugular vein, and this artery then bifurcates into the internal and external carotid arteries between C3 and C4, at the superior border of the thyroid cartilage.[4]

The internal carotid artery ascends posterior to the external carotid artery to enter the cranium and supply the head with blood. The external carotid artery branches immediately post-bifurcation and supplies the majority of structures in the neck.[6]

The four most proximal branches of the external carotid supply several neck structures, while the remaining four of eight branches provide blood supply elsewhere in the body. The superior thyroid artery branches anteriorly and descends to supply the superior pole of the thyroid gland, as well as the thyrohyoid and cricothyroid muscles, and the internal larynx as the superior laryngeal artery branch.

The posterior aspect of the external carotid artery yields the ascending pharyngeal artery, which dives deep through the pre-tracheal fascia and supplies the pharyngeal constrictor muscles.

Another anterior surface branch of the external carotid is the lingual artery, just deep to the mylohyoid muscle to supply tongue muscles and the sublingual salivary gland.

The last of the four anterior cervical branches of the external carotid is the facial artery, which branches off the external carotid just superior to the lingual artery. After passing deep to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, it continues superficially to the mylohyoid muscle and hooks over the inferior edge of the mandible, anterior to the masseter muscle. Many numerous branches of the facial artery supply the face, soft palate, and submandibular salivary glands on either side.[7]

Lymphatic Drainage of the Anterior Cervical Region

The anterior cervical neck region is also home to many lymph nodes that drain the head and neck structures and are essential for metastasis of head and neck cancers and spread of head and neck infections.[8]

Lymphatic drainage of this area of the neck is vast. It includes the anterior superficial and deep cervical lymph nodes, which further drain the sternocleidomastoid region. The anterior cervical lymph nodes and lateral jugular lymph nodes drain the nuchal region and the larynx, trachea, and thyroid regions.

Facial lymphatic drainage in the area includes the submandibular nodes, which are deep to the submandibular gland within the submandibular triangle and drain the oral cavity and lower face soft tissue structures. Another important lymphatic drainage basin of the anterior cervical neck is the submental lymph nodes, which lie in the submental triangle and drain the floor of the mouth, tongue apex, and lower lip.[9]

Most importantly, circulation and lymphatics unify in proximity to the anterior cervical region. The entire body drains into the thoracic duct, and that drains into the left internal jugular and subclavian veins. However, the head and neck, right upper limb, and hemithorax all drain lymphatics into the right lymphatic duct and then into the right internal jugular and subclavian veins.

Nerves

Many important nerves in this region innervate local structures and other structures in the head and neck.

Various Functions of Cranial Nerves

Of note, this area houses sections of major cranial nerves. For instance, branches of the glossopharyngeal (CN IX) and vagus nerves (CV X) innervate the carotid body and carotid sinus, both of which are key structures in homeostasis. These are involved in blood pressure regulation and measuring blood oxygen levels, respectively.[10]

Additionally, the vagus nerve runs between the carotid artery and the internal jugular vein in the carotid sheath. Its pharyngeal branches supply motor input to the internal muscles of the pharynx. One of its major branches, the superior laryngeal nerve branches into the internal and external laryngeal nerves, which supply sensation to the larynx superior to the vocal cords and innervation to the cricothyroid muscle, respectively.[11]

Another important cranial nerve, hypoglossal (CN XII) nerve, can be found in this region descending posterior to the internal carotid artery as it crosses into the carotid triangle at the lateral surfaces of the bifurcated carotid arteries. It will course deep into the submandibular triangle to innervate intrinsic tongue muscles.

Ansa Cervicalis Nerves

A major loop of nerves in the anterior triangle is part of the ansa cervicalis in the cervical plexus. The superior root from the anterior ramus travels with CN XII and descends the anterior surface of the carotid sheath. The nerve for the thyrohyoid is a branch of the superior root that travels with the hypoglossal to innervate this muscle. The inferior root originates from the anterior rami of the C2-C3 spinal nerves and descends. These two loops then join around C5 vertebrae and give off branches to innervate the omohyoid, sternohyoid, and sternothyroid muscles.[12]

Muscles

Muscles in the anterior cervical region divide relative to the hyoid bone, such that the suprahyoid muscles lie above, and infrahyoid muscles lie below. The suprahyoid muscles include the stylohyoid, digastric, mylohyoid, and geniohyoid muscles. The infrahyoid muscles include the omohyoid, sternohyoid, thyrohyoid, sternothyroid muscles.

The Suprahyoid Muscles

The suprahyoid muscles are aforementioned. Their general function is to elevate the hyoid bone. The stylohyoid divides the carotid from the submandibular triangle. It originates from the styloid process at the skull base and inserts on the hyoid body and digastric tendon. The facial nerve innervates this muscle and retracts the bone during swallowing. The digastric muscle primarily functions to depress the mandible and elevate the hyoid bone. This muscle is composed of an anterior and posterior belly joined by a tendon that attaches to the body of the hyoid bone. The anterior belly, innervated by the mandibular division of trigeminal nerve (CN V), arises from the internal surface of the mandible. The posterior belly, innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII), arises from the medial surface of the mastoid process.[13]

The mylohyoid forms the floor of the oral cavity, as well as the deep surfaces of the submandibular and submental triangles. It originates from the internal surface of the mandibular body and inserts on the hyoid bone body and contralateral mylohyoid muscle in the midline. It receives innervation from the branches of the inferior alveolar branches of the trigeminal branch, mandibular division. This muscle elevates the floor of the oral cavity. The blood supply of this artery is the mylohyoid branch of the inferior alveolar artery.

The geniohyoid is a narrow muscle superior to the medial border of the mylohyoid muscle, so named for its passage from the chin to the hyoid bone. It functions to carry the hyoid bone upward, as well as the tongue. It originates in the inferior mental spine of the mandible and inserts on the hyoid bone.

The Infrahyoid Muscles

The strap, or infrahyoid, muscles are four grouped pairs of anterior cervical muscles, as previously listed. Their primary function is to depress the hyoid bone and larynx during speech and swallowing maneuvers. All except the thyrohyoid receive innervation from the cervical plexus (C1-C3), particularly the ansa cervicalis.

The sternohyoid muscles and sternothyroid muscles are both innervated by the ansa cervicalis. The former originates on the posterior surface of the manubrium sterni and inserts onto the medial lower border of the hyoid bone. The sternothyroid originates similarly and inserts on the oblique line of the thyroid cartilage.

The omohyoid superior belly originates in the intermediate tendon and inserts onto the hyoid bone, whereas the inferior belly originates on the superior scapular border and inserts onto the intermediate tendon. Of the four, only the thyrohyoid is innervated by cervical spinal nerve one via the hypoglossal nerve.[14]

Physiologic Variants

Many naturally occurring variants can occur in the plethora of nerves and vasculature in this area, of which a few are as follows.

Anatomic variations in the internal jugular vein exist. In a retrospective study on patient imaging, the right internal jugular vein as found to be typically larger than the left. A majority of veins are found lateral to the common carotid artery; however, some can be found anterior to or even rarely medial or posterior to the common carotid artery. Some may also be hypoplastic in some instances. Computed tomography is the preferred method to understand jugular anatomy.[15]

Surgical Considerations

Surgeons operating in this area must consider avoiding injury to crucial structures and finer neuro vasculature.

During procedures such as carotid endarterectomies to alleviate internal carotid artery stenosis secondary to atherosclerosis, caution is necessary to protect the roots of the ansa cervicalis. Other possible sites of injury include the carotid branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve and the carotid sinus. Additionally, anesthesia teams must take care that any excessive stimulation to this area can lead to inappropriate intraoperative hypoxia, hypotension, or bradycardia.[5]

Injuries to the vagus nerve in this area can lead to hoarseness secondary to insult to the recurrent laryngeal nerve, dysphagia, or aspiration issues.

Any thyroid or parathyroid surgeries should involve careful dissection of all anterior cervical neck structures using the division of the strap muscles to visualize these structures within the deep cervical fascia. In this area, of note, surgeons should keep an eye out for superior laryngeal artery and nerve bundle at the superior pole of the thyroid. The artery should be ligated; otherwise, the larynx could lose all vascular supply. Injury to the nerve at this level can also lead to hoarseness. Any bilateral injury to the superior laryngeal nerve can cause loss of the laryngeal cough reflex and can lead to chronic respiration issues.[16]

Clinical Significance

The carotid triangle contains many superficial and surgically accessible vessels and nerves. This clinical approach includes any number of procedures involving the carotid arteries, internal jugular vein, and hypoglossal nerve.

Clinical Significance of the Carotid Body & Sinus

At the bifurcation of the common carotid lies the carotid sinus, a baroreceptor hub innervated by the carotid branch of the ninth cranial nerve. Any increased pressure in the circulatory system can cause elevated stretch tension in the sinus, leading to an autonomic adjustment causing lowered blood pressure, reduced heart rate, and even decreased respiratory rate. Clinicians can attempt carotid sinus massage, which can terminate cardiac arrhythmias such as supraventricular tachycardia in some individuals.[17]

This area is also significant for the carotid body, a chemoreceptor for blood oxygen contents which can become overstimulated or hyperplastic in chronically hypoxic conditions like high altitudes or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.[18]

Clinical Significance of the Internal Jugular Vein

The internal jugular vein has considerable significance. In patients with congestive heart failure or inferior wall infarctions of the myocardium, the back-flow and increased pressure in the right heart circulatory system can cause engorgement of the vein. A jugular venous pressure pulse tracing can be used to view the waveform and track various cardiovascular pathologies.

Clinicians can also use this vein for establishing catheter access for mediations, dialysis, and parenteral nutrition. There remains a risk of hematoma or puncture and hemorrhage if incorrect access leads into the carotid artery.[19]

Other Issues

Torticollis or cervical dystonia can present as a result of dysfunctional neuromuscular mechanisms in the anterior cervical neck region. Commonly involved are the sternocleidomastoid muscles, which can form a palpable mass. Causes include congenital causes, pain due to injury to the skin of the neck, or, most often, spasmodic dystonias triggered by stress or movement.[20][21][22]