Introduction

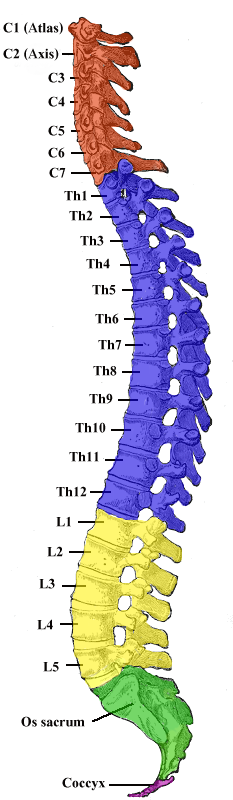

Vertebrae, along with intervertebral discs, compose the vertebral column or spine. It extends from the skull to the coccyx and includes the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions. The spine has several major roles in the body that include: protection of the spinal cord and branching spinal nerves, support for thorax and abdomen, and enables flexibility and mobility of the body. The intervertebral discs are responsible for this mobility without sacrificing the supportive strength of the vertebral column. The thoracic region contains 12 vertebrae, denoted T1-T12. The intervertebral discs, along with the laminae, pedicles, and articular processes of adjacent vertebrae, create a space through which spinal nerves exit. The thoracic vertebrae, as a group, produce a kyphotic curve. Thoracic vertebrae are unique in that they have the additional role of providing attachments for the ribs.[1][2][3]

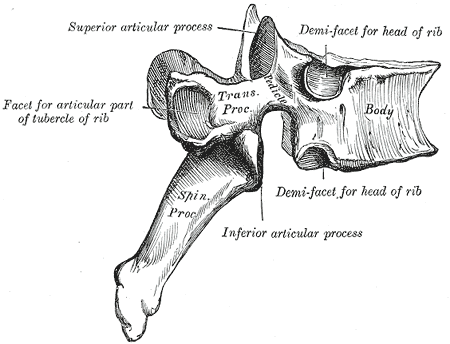

Typical vertebrae consist of a vertebral body, a vertebral arch, as well as seven processes. The body bears the majority of the force placed on the vertebrae. Vertebral bodies increase in size from superior to inferior. The vertebral body consists of a trabecular bone, which contains the red marrow, surrounded by a thin external layer of compact bone. The arch, along with the posterior aspect of the body, forms the vertebral (spinal) canal, which contains the spinal cord. The arch consists of bilateral pedicles, cylindrical segments of bone that connect the arch to the body, and bilateral lamina, bone segments form most of the arch, connecting the transverse and spinous processes. A typical vertebra also contains four articular processes, two superior and two inferior, which contact the inferior and superior articular processes of adjacent vertebrae, respectively. The point at which superior and articular facets meet is known as a facet, or zygapophyseal, joint. These maintain vertebral alignment, control the range of motion, and are weight-bearing in certain positions. The spinous process projects posteriorly and inferiorly from the vertebral arch and overlaps the inferior vertebrae to various degrees, depending on the region of the spine. Lastly, two transverse processes project laterally from the vertebral arch in a symmetric fashion.

Typical thoracic vertebrae have several features distinct from those typical of cervical or lumbar vertebrae. T5-T8 tend to be the most “typical” because they contain features present in all thoracic vertebrae. The primary characteristic of the thoracic vertebrae is the presence of costal facets. There are six facets per thoracic vertebrae: two on the transverse processes and four demifacets—the facets of the transverse processes articulate with the tubercle of the associated rib. The demifacets are bilaterally paired and located on the superior and inferior posterolateral aspects of the vertebrae. They are positioned so that the superior demifacet of the inferior vertebrae articulates with the head of the same rib that articulates with the inferior demifacet of the superior rib. For example, the inferior demifacets of T4 and the superior demifacets of T5 articulate with the head of rib 5. The length of the transverse processes decreases as the column descends. The positioning of the ribs and spinous processes greatly limits flexion and extension of the thoracic vertebrae. However, T5-T8 have the greatest rotation ability of the thoracic region. Thoracic vertebrae have superior articular facets that face in a posterolateral direction. The spinous process is long, relative to other regions, and is directed posteroinferiorly. This projection gradually increases as the column descends before decreasing rapidly from T9-T12. The intervertebral disc height is, on average, the least of the vertebral regions.

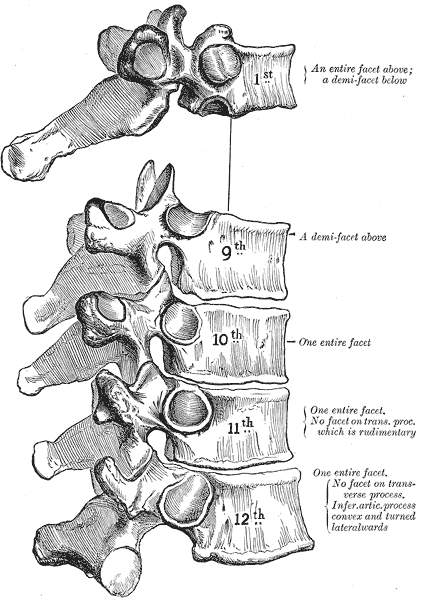

There are three atypical vertebrae found in the thoracic region:

The superior costal facets of T1 are “whole” costal facets. They alone articulate with the first rib; C7 has no costal facets. T1 does, however, have typical inferior demifacets for articulation with the second rib. T1 also has a long, almost horizontal spinous process, similar to a cervical vertebra that may be as long as the vertebra prominens of C7.

T11 and T12 are atypical in that they contain a single pair, “whole,” costal facet that articulate with the 11 and 12 ribs, respectively. They also lack facets on the transverse processes. It varies by individual, but T10 may resemble the atypical nature of the 11 and 12 vertebrae. When that is the case, T9 lacks an inferior demifacet, as it would not be needed to articulate with the 10th rib.

Additionally, T12 is unique in that it represents a transition from the thoracic to the lumbar vertebra. It is thoracic in that it contains costal facets and superior articular facets that allow for rotation, flexion, and rotation. It is lumbar in that it has articular processes that do not allow for rotation, only flexion, and extension. It also contains mammillary processes, small tubercles located on the posterior surface of the superior articular processes, which allow for attachment for the intertransversarii and multifidus muscles.[4]