Introduction

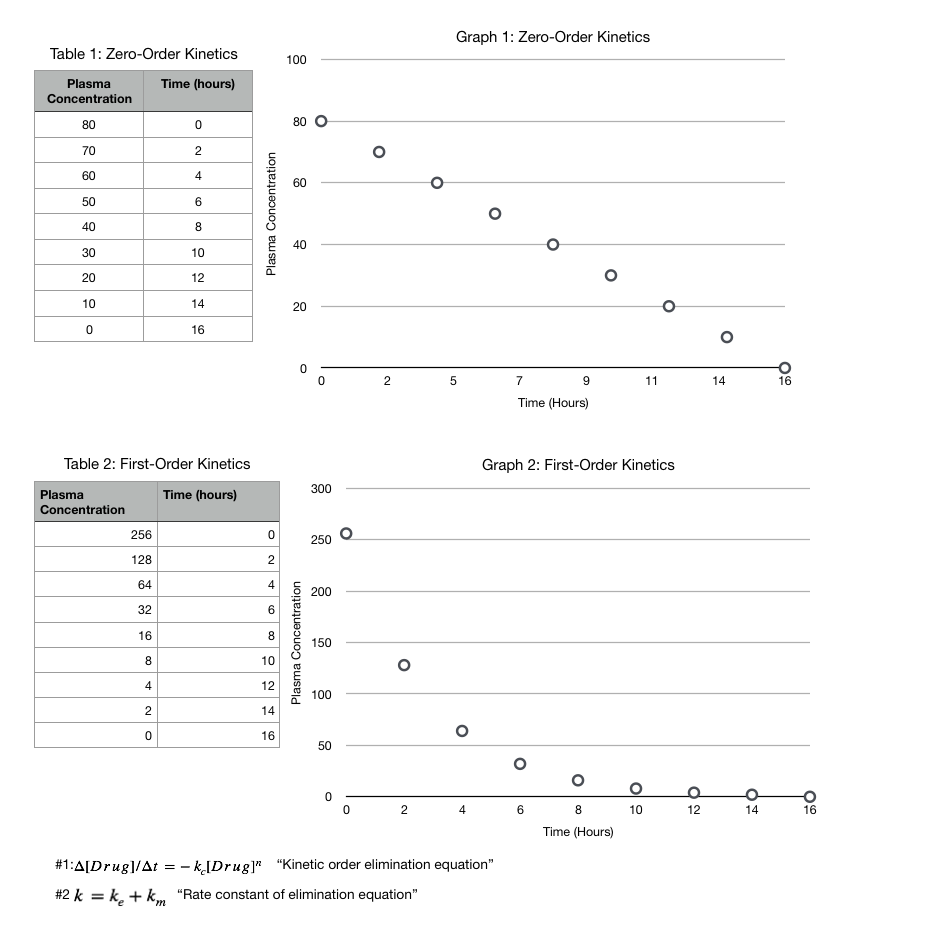

As the human body ingests substances and medications, it utilizes a variety of metabolism and elimination processes. The second focus of this topic is zero and first-order kinetic elimination, which is clinically useful in achieving a therapeutic level of medication and prognostically assessing toxicity levels and implementing treatment. For simplicity, the following discussion is specific to a one-compartment model, which views the human body as a homogeneous unit. Lastly, while most drugs undergo elimination via first-order kinetics, a firm understanding of both zero and first-order kinetics is crucial in a clinical setting, as there can be fluidity between the 2 types of elimination with the same specific substance (see Graph. Zero- and First-Order Elimination and Equations).[1]

Issues of Concern

Determination and understanding of how a particular substance is eliminated are important when administering medications to achieve a therapeutic level and when assessing a patient who ingested a toxic substance. Specifically, regarding toxicology, if the ingested substance is unknown to the patient and practitioner, routine blood/plasma testing of the substance and analysis of the decline in concentration aids in identifying the ingested substance. For example, suppose the substance follows a zero-order elimination. In that case, the amount eliminated depends on time and not the amount ingested, in contrast to first-order kinetics, in which the amount eliminated depends on the maximum blood/plasma concentration and not on time. Furthermore, once the substance and its properties are understood, proper treatment may be given to a patient who ingested a toxic substance.

To achieve the desired therapeutic level of a medication, a clinician must understand the elimination order and utilize the information in subsequent dosing to maintain the therapeutic concentration over a set period. Misunderstanding of kinetic elimination may lead to patients experiencing toxic symptoms and could lead to other iatrogenic adverse effects up to and including death.

Organ Systems Involved

The kidneys are the primary excretory system, whereas the hepatic system is the main site involved in drug metabolism. Other sites of metabolism include the gastrointestinal tract, pulmonary system, kidneys, and skin. An important concept to understand is any impairment of the described systems may alter how a therapeutic level of medication is achieved and can predispose patients to toxicity symptoms with a dose that would otherwise be well-tolerated in a healthy individual. Both metabolism and excretion are combined to form the rate constant of elimination, which is useful in determining the order of elimination. This equation appears in "Equation No. 2", where "k" represents the rate constant of elimination, and "km" and "ke" represent the rate constant for metabolism and the rate constant for excretion, respectively.

Function

The fundamental difference between zero and first-order kinetics is their elimination rate compared to total plasma concentration. Zero-order kinetics undergo constant elimination regardless of the plasma concentration, following a linear elimination phase as the system becomes saturated. A simple analogy would be an athlete signing an autograph on a picture. Regardless of the number of photographs that must be signed, the athlete can only sign 1 autograph every 15 seconds. The rate-limiting factor of this analogy and zero-order kinetics is time.

First-order kinetics proportionally increases elimination as the plasma concentration increases, following an exponential elimination phase as the system never achieves saturation. Furthermore, when attempting to obtain a therapeutic level of plasma concentration or regarding drug toxicity, one must utilize their knowledge of a particular drug elimination kinetic. The entire team can sign the photographs to utilize the same analogy. The more photographs there are to sign, the more athletes can sign. The initial concentration is the rate-limiting factor of this analogy and in first-order kinetics.

In the case of autographs, if the number of needed autographed photos exceeds the number of available athletes, the first-order elimination becomes zero-order. As described above, the system of first-order kinetic elimination can become saturated, forcing a zero-order kinetic model to take place. Once the concentration falls below a certain level, a first-order kinetic elimination is again seen as the system is no longer saturated.[2][3][4]

Mechanism

Both zero and first-order kinetics derive from the same equation. As seen in "Equation No. 1 "Kinetic order elimination equation," where delta [drug] represents the change in plasma concentration of the drug divided by time, "n" represents either first or zero-order elimination with 1 or 0, respectively, and "-Kc" represents a constant. For example, when n = 1, the change in drug plasma concentration divided by time is proportional to the amount of drug initially given, showing the rate-limiting factor being the initial concentration. In contrast, when n = 0, [Drug]0 = 1, the change of drug plasma concentration is equal to the constant, -Kc. Thus demonstrating how the rate-limiting factor is time.

The same principles with zero and first-order kinetics are demonstrable on a graph. As seen in "Graph 1: Zero-order kinetics", regardless of the plasma concentration of a substance, the same amount is limited over 2 hours. Thus, the graph demonstrates a linear slope. Compared to "Graph 2: First-order kinetics," the exponential curve of the graph illustrates how a larger plasma concentration implies a larger amount eliminated in 2 hours.[5][6]

Clinical Significance

When administering medications, one must fully understand the mechanism of action and elimination to reduce unwanted adverse effects. Furthermore, when assessing a patient who may have either intentionally or accidentally ingested a toxic quantity of a substance, knowing that the substance's elimination properties aid treatment and the disease course.

For example, in the case of methanol ingestion, urgent treatment is necessary. Methanol itself results in sedation but is generally nontoxic. The toxicity of methanol is a function of its metabolites. As methanol follows zero-order kinetic elimination, a clinician can understand that the actual danger lies in the time from the ingestion, not the total amount. In contrast to methanol, other specific medications that show zero-order elimination are salicylates, omeprazole, fluoxetine, phenytoin, and cisplatin, which, when ingested at toxic levels, achieves a higher concentration of the substance within the body over time versus the same amount of the substance that uses first-order elimination.[7] A firm understanding of the above-described concepts helps reduce the adverse effects of medications on patients and leads the practitioner to choose better treatments for patients experiencing toxicity symptoms.