Continuing Education Activity

Z-plasty is a common reconstructive surgical technique used for scar revision and contracture release. It involves the transposition of two opposing triangular flaps that then changes the direction of a scar so that it is better aligned with natural skin folds or relaxed skin tension lines and either less visually apparent or less restrictive to movement. The technique has been applied to numerous areas of the body, from fingers to the nose, the chest to the palate, the face, the eye, the ear, and many others besides. A benefit of this procedure over other scar revision techniques is that it does not necessarily require skin excision and is therefore considered a tissue-sparing option. This activity illustrates how Z-plasty is performed and highlights the interprofessional team's role in managing chronic scars.

Objectives:

- Summarize the indications for a Z-plasty.

- Describe the technique of Z plasty.

- Review the contraindications to performing a Z-plasty.

- Explain interprofessional team strategies that enhance care coordination and communication to advance the management of scars and improve patient outcomes in patients receiving a Z-plasty procedure.

Introduction

Z-plasty is a commonly employed transposition flap utilized in plastic and reconstructive surgery to revise scars.[1][2] The technique has been applied to numerous areas of the body, from fingers to the nose, the chest to the palate, the face, the eye, the ear, and many others besides.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] Previously referred to as “converging triangular flaps,” Z-plasty involves the transposition of two or more opposing flaps raised along a shared axis. A benefit of this procedure over other scar revision techniques is that it does not necessarily require skin excision if the quality of the skin overlying the scar is aesthetically acceptable for use in the reconstruction. Z-plasty transposition changes the direction of a scar, so it is more easily hidden within a border between facial regions or relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs). Additionally, this technique may be employed to release scar contracture after burns.[11] Common variants of the basic Z-plasty include the planimetric Z-plasty, double-opposing Z-plasty, compound Z-plasty, skew Z-plasty, and running/serial Z-plasty.

The earliest records of this technique date back to the early 1800s in a publication at the Philadelphia Hospital Department of Surgery, when Horner described using single transposition flaps. The geometry of what clinicians considered the Z-plasty then was not the same as it is today. At the turn of the century, the “Z-plasty method” became more popular when a publication by Berger in 1904 suggested the use of equal limbs and equal angles. In 1914, Morestin proposed using multiple Z-plasties to address more extensive scarring. However, it was Limberg, in 1929, who delved into the rotational and advancement dynamics of the flaps commonly employed today.[12]

Anatomy and Physiology

Anatomy of the Skin

The skin is composed of two distinct layers, the epidermis, which provides a permeable barrier to the outside world, and the dermis, which supports the overlying epidermis. The epidermis consists of five layers, from superficial to deep: the stratum corneum, the stratum lucidum (which is only present in the palms and soles of the hands and feet), the stratum granulosum, the stratum spinosum, and the stratum basale. The underlying dermis consists of two layers, the papillary dermis, which interdigitates with the epidermis, and the deeper reticular dermis, whose collagen and elastin provide the skin its strength and elasticity as well as housing the pilosebaceous units.[13] Integumentary blood supply is provided by the subdermal plexus, a collection of blood vessels located on the undersurface of the dermis that gives off vertical branches up through the layers of the skin; this arrangement that necessitates elevation of skin flaps in a subdermal plane in most instances.[14]

Biomechanical Properties of the Skin

In addition to the histological and vascular anatomy of the skin, it is important to understand its biomechanical properties when planning local flap surgery, such as Z-plasty flap transposition. There is a well-defined orientation to the direction in which skin stretches best in order to facilitate the closure of defects, and this is determined by the orientation of dermal collagen fibers. First described in 1861, the predominantly parallel lines that best hide incisional scars are known as Langer lines.[15] Placing incisions within these lines or within the borders of aesthetic subunits generally makes the resulting scars less noticeable than they would be if they were oriented across the Langer lines or subunit boundaries. In the face, the analogous concept is that of relaxed skin tension lines, first described by Borges in 1984, but these lines, while similar to Langer lines in appearance and implication for surgery, are caused by the action of the underlying mimetic musculature of the face, perpendicular to whose contraction they are aligned.[16]

Perpendicular to the RSTLs is the lines of maximum extensibility, which determine the vectors along which skin is most easily advanced to close a defect. When skin is advanced, two additional concepts come into play: mechanical creep and stress relaxation. Mechanical creep is the ability of the skin to stretch under constant tension due to displacement of interstitial fluid, while stress relaxation is the phenomenon in which less tension is required over time to maintain skin in a constant stretched position.[17] Undermining the skin in a subdermal plane will provide further reduction of closing tension on a wound, but it is important to note that undermining more than 2 to 4 cm from the wound edge is unlikely to decrease tension further.[18][19][20]

When attempting to minimize standing cutaneous deformities at the pivot points, transposition of Z-plasty flaps requires wide undermining of surrounding tissue in order to distribute both tension and compression forces and facilitate closure. Doing so will also help to avoid closing under tension, which is important because of the deleterious effect tension produces on perfusion of the tips of the flaps and the wound edges; the use of creep and stress relaxation permit closure of defects with local flaps that would otherwise require recruitment of distant tissue for reconstruction. The surgeon should also realize that the rotations of the Z-plasty flaps during transposition result in the loss of a small amount of flap length, which makes the classic Z-plasty planning table slightly imprecise because it is based solely on geometry; fortunately, creep and stress relaxation generally offset this shortcoming of the Z-plasty technique.[21][22]

Indications

The primary indication for a Z-plasty is the lengthening and reorientation of a scar to improve cosmetic appearance or function.[23][24]

Notable Uses

- Facial scar camouflage

- Release of motion-limiting scarring, such as on an extremity or digit

- Burn wound contracture release

- Release of stenosis of a circular structure, such as the nasopharynx or nasal vestibule

- Restoration of facial landmarks distorted by scarring, such as canthal webbing or ectropion

- Lengthening and closure of a cleft palate

Contraindications

Common contraindications to Z-plasty transposition include a lack of available healthy tissue to transfer as well as keloid and hypertrophic scarring tendencies. Additionally, surgeons should use caution when considering this technique in patients with conditions that may adversely affect wound healing: vasculopathy, uncontrolled diabetes, prior radiation exposure, active infection, the persistent inflammatory state in burn patients, and patient noncompliance or anticipated noncompliance with perioperative care regimens.

Equipment

The equipment needed to perform a Z-plasty transposition is similar to that required for other cutaneous surgery:

Preoperative Items

- Surgical antiseptic scrub

- Surgical marker

- Local anesthetic

Intraoperative Items

- Scalpel (No. 15 blade)

- Forceps

- Needle holder

- Dissecting scissors

- Suture scissors

- Surgical gauze

- Retractors or skin hooks

- Suture material

- Electrocoagulation device

Postoperative Items

- Wound dressing

- Antibiotic ointment

Personnel

Smaller Z-plasties may be performed as in-office procedures, requiring only a surgeon and an assistant, with or without an additional nurse present. Larger or more complicated operations, such as serial Z-plasties for scar release or Furlow palatoplasty, are better performed under general anesthesia in an operating room and thus require an anesthesia provider and full surgical staff.

Preparation

Preparation involves discussing the anticipated results with the patient, including the expected change to the tension and vector of the scar and any distorted structures, as well as the addition of two more incision limbs. Careful attention to the geometry of the Z-plasty, particularly the length, orientation, and location of the oblique incision limbs, should be paid, and the flaps should be marked appropriately. As with many other comparatively minor surgeries, such as upper lid blepharoplasty and direct brow lifting, the preoperative decision-making and incision marking process require the most thought, while the procedure itself is comparatively straightforward.

Technique or Treatment

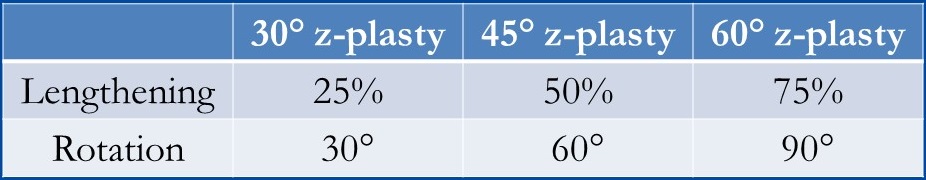

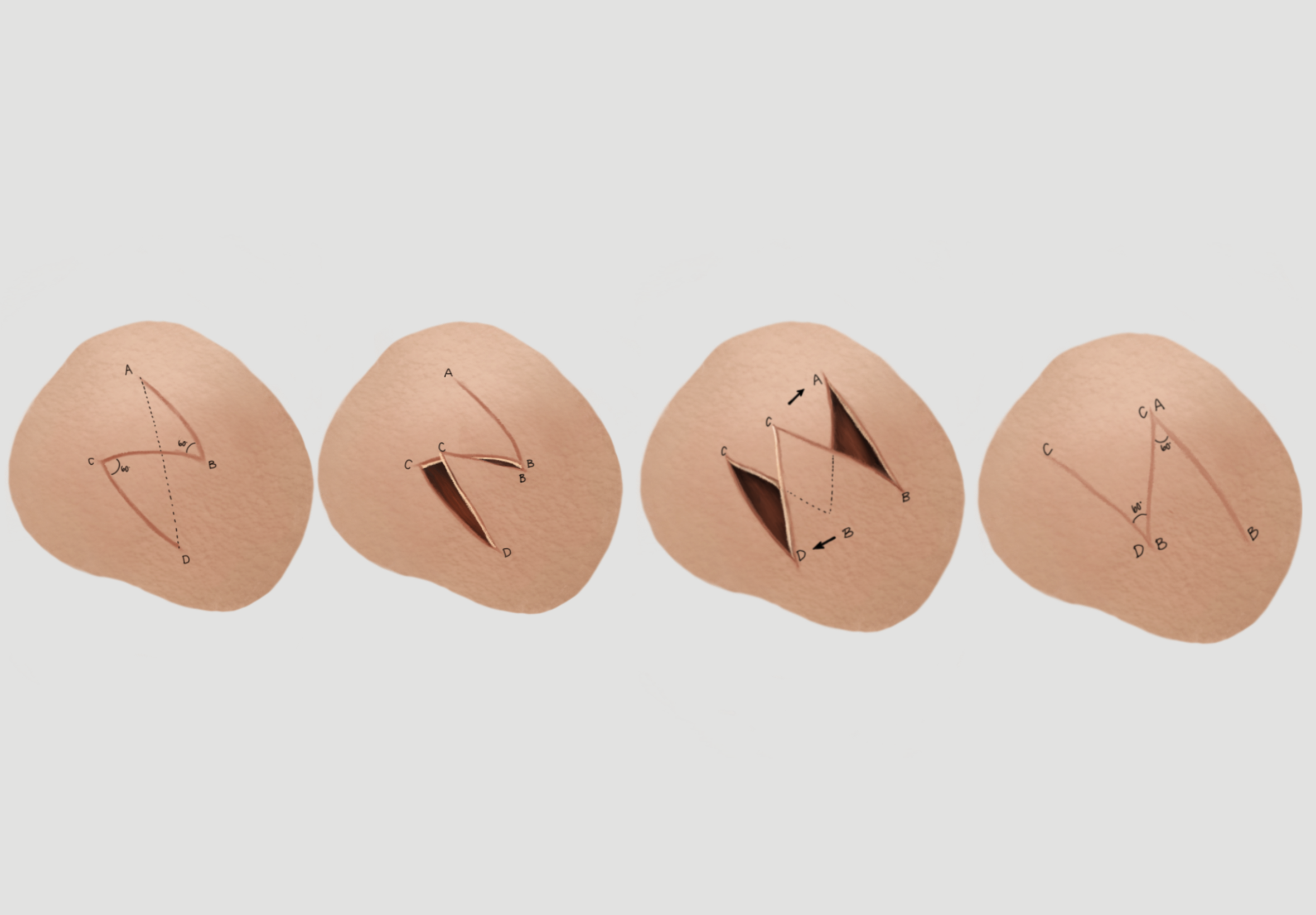

After the area has been prepared with a sterile solution, the two oblique "arms" of the Z-plasty are drawn at both ends of the scar to be revised. Generally, it is preferable to mark the Z-plasty prior to injecting the local anesthetic, as adding volume will distort the tissue. There are myriad options for flap design, with larger angles resulting in greater lengthening and rotation of the scar and smaller angles causing the opposite. The prototypical Z-plasty has equal-length arms with 60-degree take-off angles from the central scar, which will rotate the scar by 90 degrees and lengthen it by 75%, but different angles may be used, and the two limbs do not necessarily have to have the same lengths or angles; these asymmetric Z-plasties are known as "skew Z-plasties," and are most commonly used when an anatomic structure prevents a Z-plasty design with symmetric limbs.

When angles greater than 60 degrees are required, some surgeons will divide the angle into two flaps (e.g., a 90-degree angle split into two flaps of 45 degrees each) that will both come off the same end of the primary scar, thus resulting in a "compound" Z-plasty. The advantage of this technique is that it minimizes standing cutaneous deformities but at the expense of an additional scar. When scars are particularly long, it may be helpful to add more limbs to the Z-plasty along the length of the scar in addition to those placed at the ends; this is called a "serial" or "running" Z-plasty (see figure).

After injection of local anesthetic and sterile preparation of the surgical field, the central scar is excised, and hemostasis is obtained. The Z-plasty limbs are then incised with a No. 15 scalpel, and the flaps elevated in a subdermal plane, assuming the procedure is being performed on the skin - a submucosal or submuscular plane may be required in other areas, such as the palate (see below). The wide undermining of the surrounding area - roughly 2 to 4 cm - should be performed to facilitate flap transposition. Hemostasis is then obtained again, taking care to avoid aggressive electrocautery on the undersurface of the flaps to minimize the chance of flap necrosis due to disruption of the subdermal plexus. The flaps are then transposed, and the incisions are closed in layers, providing sufficient tissue depth.

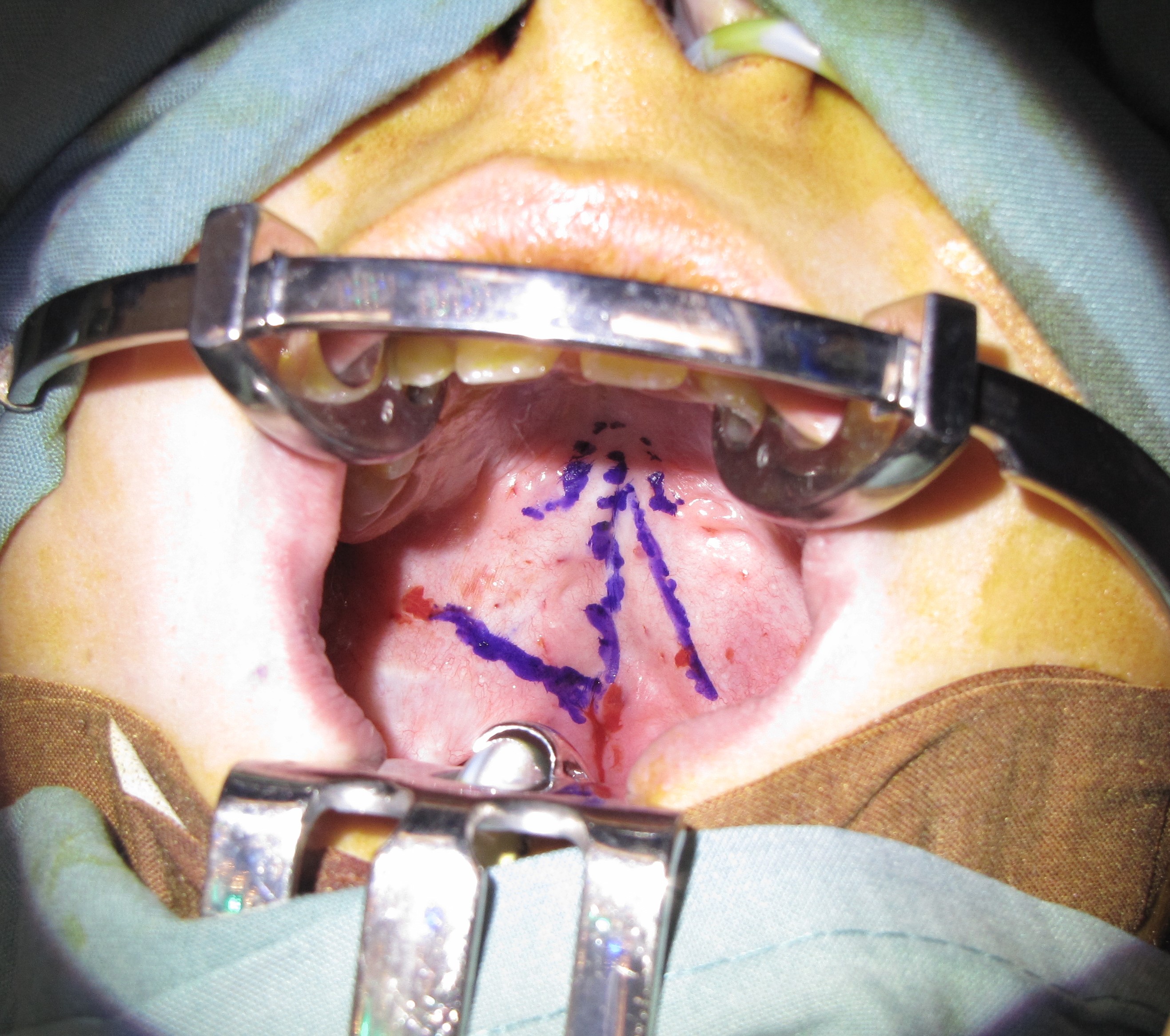

An important application of the Z-plasty in a non-cutaneous location is that of the cleft palate. The Furlow double-opposing Z-plasty technique, originally described in 1986, is commonly employed to repair clefts of the soft palate while simultaneously lengthening the palate and reorienting the muscles to improve velopharyngeal function.[25] In this procedure, the cleft serves as the central limb of the Z-plasty, taking the place of the scar, and the other limbs are incised near the posterior border of the soft palate and near the hard-soft palate junction (see figure). The posteriorly-based flap contains muscle and mucosa, while the anteriorly-based flap contains mucosa only, but there is a deeper Z-plasty that is performed along the nasal mucosa as well, using a mirror image flap design such that the two posteriorly-based flaps rotate the sling of the tensor veli palatini muscle into the anatomically correct transverse orientation.

Another common use of the Z-plasty is the release of stenosis, which is analogous to simpler scar releases. In these applications, the central limb of the Z-plasty should be designed along the rim of the stenosis or along the free edge of the scar web, which may be initially counterintuitive to the surgeon, who would be tempted to divide the scar transversely. By placing the central segment of the Z along the scar rather than across it, the flaps can then be transposed in such as way as to lengthen, i.e., release the stenosis or web.

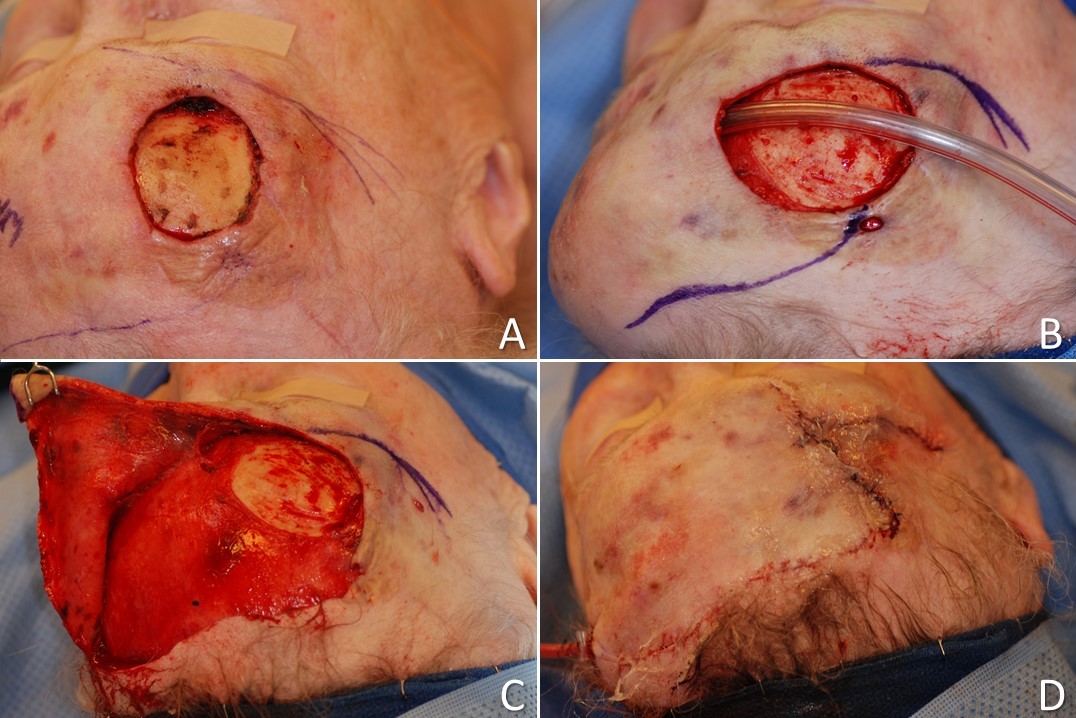

Lastly, several local flap techniques include Z-shaped designs without being true Z-plasties because no flap transposition takes place - only advancement and/or rotation. Examples of these are the "planimetric" Z-plasty, in which opposing triangles of tissue are removed to allow triangular flaps to advance and close a defect without leaving a linear scar along the axis of the original lesion or scar; this technique is very similar to S-plasty closure, which is an offset variant of simple fusiform excision and closure. The O to Z-plasty is another good example, in which a circular defect is closed with a Z-shape due to the advancement and rotation of two flaps into its center, even though the flaps do not undergo transposition and therefore do not constitute a true Z-plasty (see figures). On the other hand, transposition of a rhombic flap does constitute the use of a true Z-plasty, albeit a skewed Z-plasty in which one flap does nearly all of the movement and the other, because of an obtuse angle, moves very little - the evidence for rhombic flaps being Z-plasties is clear, however, when the final Z-shaped scar is observed (see figure).

Complications

Complications from Z-plasty transposition parallel those of any other cutaneous flap surgery: pain, bleeding, infection, worsened scarring, and need for further surgery. Because of the complicated geometry of Z-plasty transposition, there exists the opportunity for misjudgment of flap orientation or length as well as skin laxity or viability. In the event of such an error, or in the case of poor tissue quality or vascularity, the resulting postoperative scar may appear worse than the initial one, or distortion of surrounding tissues may be exacerbated.

Because the technique involves raising flaps, more specific risks include hematoma development and venous congestion, either of which may result in flap necrosis and/or wound dehiscence. Necrosis is made more likely by poor tissue vascularity, excessively thin flaps that do not incorporate the subdermal plexus, or overly narrow flaps (<30 degrees at the tip). Conversely, flaps that are too wide (<60 degrees at the tip) are more likely to result in standing cutaneous deformities ("dog ears") that are likely to require revision at a later stage.

Clinical Significance

Z-plasty is a common transposition flap technique used in plastic and reconstructive surgery to revise scars. The technique can also be used to prevent the contracture of linear scars, decrease scar length, realign malpositioned tissues, close cutaneous defects, and alleviate stenosis. While a single Z-plasty may be employed to manage a small scar, a serial/compound Z-plasty may be used to address longer or wider scars. Understanding the fundamental principles and surgical techniques of basic Z-plasty and its variants provides the surgeon with a powerful tool for scar management.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Z-plasties are typically used by plastic surgeons but are also routinely employed by facial plastic surgeons, otolaryngologists, ophthalmologists, urologists, orthopedic surgeons, and dermatologists, among others. The scope of the procedure may be limited, with the surgery occurring under local anesthesia in a clinic, or it may be significant, requiring a full operating room and staff operating as a coordinated interprofessional team. For this reason, ensuring that not only is there a surgeon experienced with flap transposition techniques but also assistants familiar with the necessary instrumentation and nurses comfortable managing the postoperative course of patients who have undergone Z-plasty is critical to optimizing functional and aesthetic outcomes. [Level 5]