Definition/Introduction

In 1986, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed the WHO analgesic ladder to provide adequate pain relief for cancer patients.[1] The analgesic ladder was part of a vast health program termed the WHO Cancer Pain and Palliative Care Program, aimed at improving strategies for cancer pain management through educational campaigns, creating shared strategies, and developing a global network of support.

This analgesic path, developed following the recommendations of an international group of experts, has undergone several modifications over the years and is currently applied for managing cancer pain but also acute and chronic non-cancer painful conditions due to a broader spectrum of diseases such as degenerative disorders, musculoskeletal diseases, neuropathic pain disorders, and other types of chronic pain. The efficiency of the strategy is debatable and yet to be proven through large-scale studies.[2] Nevertheless, it still provides a simple, palliative approach to reducing pain-related morbidity in 70% to 80% of the patients.[3]

The original ladder mainly consisted of three steps:

- First Step - Mild pain: non-opioid analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen with or without adjuvants

- Second Step - Moderate pain: weak opioids (hydrocodone, codeine, tramadol) with or without non-opioid analgesics and with or without adjuvants

- Third Step - Severe and persistent pain: potent opioids (morphine, methadone, fentanyl, oxycodone, buprenorphine, tapentadol, hydromorphone, oxymorphone) with or without non-opioid analgesics, and with or without adjuvants[4]

Adjuvant refers to a vast set of drugs belonging to different classes. Although their administration is typically for indications other than pain treatment, these medications can be of particular help in various painful conditions. Adjuvants, also called co-analgesics, include antidepressants, including tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) such as amitriptyline and nortriptyline, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) such as duloxetine and venlafaxine, anticonvulsants like gabapentin and pregabalin, topical anesthetics (e.g., lidocaine patch), topical therapies (e.g., capsaicin), corticosteroids, bisphosphonates, and cannabinoids.[5][6][7] Interestingly, although adjuvants are coadministered with analgesics, they are indicated as a first-line treatment option for treating specific pain conditions. For instance, the European Federation of Neurological Societies (ENS) recommended duloxetine, anticonvulsants, or a TCA for painful diabetic neuropathy treatment.[8]

The fundamental concept of the ladder is that it is essential to have adequate knowledge about pain, to assess its degree in a patient through proper evaluation, and to prescribe appropriate medications. As many patients will receive opioids eventually, it is essential to balance the optimum dosage with the side effects of the drug. Moreover, opioid rotation can be adopted to improve analgesia and reduce side effects.[4] Patients should receive education about the uses and side effects of medications to avoid misuse or abuse without compromising their benefits.

The original WHO ladder was unidirectional, starting from the lowest step of NSAIDs, including COX inhibitors or acetaminophen, and heading towards the strong opioids, depending on the patient’s pain. Scholars suggested eliminating the second level, as weak opioids contribute little to pain control.[9] In the case of moderate pain, it might be more beneficial to prescribe third-step opioids, although at reduced dosages (e.g., morphine 30 mg per day, orally). According to some authors, it should be necessary to distinguish pathways for treating acute pain from more specific treatments for use in long-lasting cancer pain.[4]

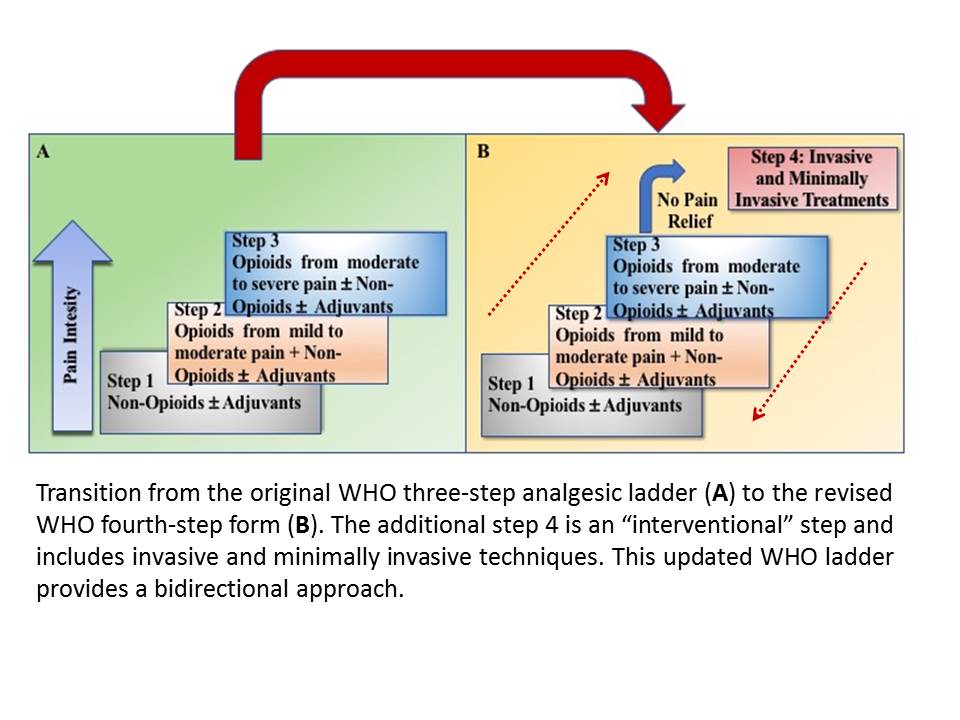

However, the real limitation of the original scale was the impossibility of integrating non-pharmacological treatments into the therapy path. Consequently, a fourth step was added to the ladder (Figure 1). This fourth step includes numerous non-pharmacological procedures that are strong recommendations for treating persistent pain, even in combination with strong opioids or other medications. This step encompasses interventional and minimally invasive procedures such as epidural analgesia, intrathecal administration of analgesic and local anesthetic drugs with or without pumps, neurosurgical procedures (e.g., lumbar percutaneous adhesiolysis, cordotomy), neuromodulation strategies (e.g., brain stimulators, spinal cord stimulation), nerve blocks, ablative procedures (e.g., alcoholization, radiofrequency, microwave, cryoablation ablations, laser-induced thermotherapy, irreversible electroporation, electrochemotherapy), and cementoplasty as well as palliation radiotherapy.[10][11][12][13]

This updated WHO analgesic ladder focuses on the quality of life and was intended as a bidirectional approach, extending the strategy to treat acute pain. For acute pain, the strongest analgesic (for that intensity of pain) is the initial therapy and later toned down, whereas, for chronic pain, a step-wise approach from bottom to top may be employed. However, clinicians should also provide de-escalation of treatment in the case of chronic pain resolution.

Issues of Concern

The analgesic ladder was designed to be easily used even by non-pain medicine experts. However, the continued referral of patients to pain specialists proves otherwise.[14] The lack of proper knowledge of drugs, underdosing and incorrect timing of drugs, fear of addiction in patients, and lack of public awareness are severe limitations that limit the adequate implementation of the strategy.[15]

Another limitation of the implementation of the strategy concerns the placement of drugs. Placing NSAIDs at the bottom of the ladder could lead to a false belief that this represents the most secure treatment. Patients often take these drugs in daily clinical practice, even for long periods. Also, long-term use of NSAIDs combined with opioids for treating moderate pain (second step) can lead to more severe side effects than those described for opioids.[16]

A significant issue of concern regards the management of pure neuropathic pain. This type of pain has complex pathophysiology and mechanisms involving different regions of the central nervous system or specific peripheral nervous system structures. An injury in these regions can trigger a cascade of events culminating in peripheral and central sensitization. In this context, opioids have little or no efficacy, and other strategies are necessary.[17] Other clinical conditions are poorly manageable following ladder rules. For example, in fibromyalgia, the drugs of the first two steps are often of poor efficacy. In contrast, using opioids can induce dangerous, addictive phenomena and be a treatment with little scientific evidence of effectiveness.

Experts in pain medicine found the ladder approach one-dimensional as it concentrated only on the physical aspects of pain. For this reason, other methods have been proposed. For instance, the International Association For The Study Of Pain (IASP) suggested adopting a therapeutic approach more focused on the type of pain (i.e., mechanism) and the mechanism of action of the drugs used to treat it. Therefore, it would be more appropriate to use steroids or NSAIDs in chronic nociceptive pain on an inflammatory basis. On the other hand, low-inflammatory nociceptive pain should receive treatment with opioids and nonopioid analgesics. Finally, neuropathic pain may require antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and specific drugs in certain rheumatologic clinical conditions (e.g., colchicine to treat gout).[18]

There are proposed suggestions to offer a more precise treatment methodology. Leung, for instance, suggested a new analgesic model represented as a platform where pain management follows a three-dimensional perspective that can combine with classical analgesics based on the pain condition.[19]

More recently, Cuomo et al. proposed the "multimodal trolley approach," which emphasizes the physical, psychological, and emotional causes of pain.[20] The model underlies the need for personalized therapy and suggests that pain is not merely a sensory discomfort experienced by the patient but also incorporates the perceptual, homeostatic, and behavioral responses to an injury or chronic illness.[21] Through this approach, clinicians can dynamically manage pain by combining several pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic strategies according to the physiopathology of pain, pain features, the complexity of symptoms, comorbidity, the physiopathological factors, and the social context. Consequently, a wide range of non-pharmacological approaches, such as yoga, acupuncture, psychotherapy, and occupational therapy, are present in specific "drawers" of the trolley and can be used according to the clinical needs and skills of the operator, as well as available resources.

The three main principles of the WHO analgesic ladder are: “By the clock, by the mouth, by the ladder.” This means that drugs should be taken regularly and at regular intervals, orally whenever possible, and analgesics should be prescribed starting at Step 1 (nonopioid analgesics) and titrated upward as needed. However, significant issues of concern with the WHO analgesic ladder have arisen over time. One problem is that it does not consider individual differences in pain tolerance or response to medications. Additionally, it is often difficult to accurately assess pain intensity when using this approach because it relies heavily on patient self-reporting. Furthermore, opioids are typically prescribed at Step 2 of the ladder without considering potential risks associated with their use, such as addiction or overdose. Finally, there is a lack of evidence-based research to support its efficacy and effectiveness in providing adequate pain relief for cancer patients.

Despite these issues of concern with the WHO analgesic ladder, it remains an essential tool for physicians in managing cancer-related pain. It provides a framework for understanding how different types of medications can be used to treat different levels of pain intensity and can help guide treatment decisions. However, more research is needed to better understand how this approach can be improved to provide effective and safe pain relief for cancer patients.[22]

Clinical Significance

Even with the drawbacks, the strategy includes a simple and effective guideline on administering analgesics that is valid even today. The main components include:

- Oral dosing of drugs whenever possible (as opposed to intravenous, rectal, etc.).

- Around-the-clock rather than on-demand administration.[15] The prescription must follow the pharmacokinetic characteristics of the drugs.

- Analgesics must be prescribed according to pain intensity as evaluated by a pain severity scale. For this purpose, a clinical examination must combine with an adequate pain assessment.

- Individualized therapy (including dosing) addresses the concerns of the patient.[9] This method presupposes that there is no standardized dosage in pain treatment. This is probably the biggest challenge in pain medicine, as the dosology must be continuously adapted to the patient, balancing desired effects and possible side effects.

- Proper medication adherence, as any dosing alterations can lead to pain recurrence.

Pain accounts for one of the top five reasons for consultation.[19] A better understanding of the physiology and psychological aspects of pain is necessary to take an ideal approach to pain control. The WHO analgesic ladder can remain a foundational treatment for chronic pain, upon which clinicians can add new modalities.

The WHO analgesic ladder has become a standard of care for cancer patients worldwide due to its effectiveness in relieving cancer pain without causing significant side effects. Studies have shown that following the WHO analgesic ladder can improve patient outcomes, reduce hospital stays, and improve quality of life. Additionally, using the ladder can help reduce opioid misuse and abuse by ensuring that opioids are only used when necessary[23].

The WHO analgesic ladder also guides titrating medications according to the needs of the patient. This allows clinicians to adjust doses to provide optimal relief from cancer pain while avoiding unwanted side effects. Additionally, it encourages clinicians to assess the response to treatment regularly to ensure that their treatment plan remains adequate.

Overall, the WHO analgesic ladder has become an essential tool for managing cancer pain due to its ability to provide adequate relief while minimizing risks associated with opioid use. Therefore, it is an important part of any comprehensive cancer care plan and should be used whenever possible to ensure optimal outcomes for patients suffering from cancer pain.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The patients should be treated with the utmost respect and empathy to make them as comfortable as possible.

Opioid administration should only be when their benefits outweigh their risks as it carries a considerable risk of dependence. Nurses should ensure they understand all directions regarding the drug, dosage, and side effects to provide the optimum amount of medication. The ordering provider should clarify any doubts regarding the drug. Pharmacists should track all prescriptions accurately and report any suspicion of drug misuse.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Pain management in chronic diseases may be time-consuming and tedious for the patient. It is essential to have regular follow-up visits to assess the progression of the disease and the efficacy of therapy and to make any necessary modifications. The patients should be encouraged to stay motivated and evaluated for any improvement or progress.

The vital signs of hospitalized patients receiving opioids should be monitored regularly to check for adverse effects; this is particularly true for the respiratory rate. In addition, bed-ridden patients should receive proper care to maintain hygiene and avoid complications like pressure ulcers and deep vein thromboses.