[1]

Khanna N, Rauh LA, Lachiewicz MP, Horowitz IR. Margins for cervical and vulvar cancer. Journal of surgical oncology. 2016 Mar:113(3):304-9. doi: 10.1002/jso.24108. Epub 2016 Feb 8

[PubMed PMID: 26852901]

[2]

Wohlmuth C, Wohlmuth-Wieser I. Vulvar malignancies: an interdisciplinary perspective. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2019 Dec:17(12):1257-1276. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13995. Epub 2019 Dec 12

[PubMed PMID: 31829526]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[4]

Boer FL, Ten Eikelder MLG, Kapiteijn EH, Creutzberg CL, Galaal K, van Poelgeest MIE. Vulvar malignant melanoma: Pathogenesis, clinical behaviour and management: Review of the literature. Cancer treatment reviews. 2019 Feb:73():91-103. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.12.005. Epub 2018 Dec 24

[PubMed PMID: 30685613]

[5]

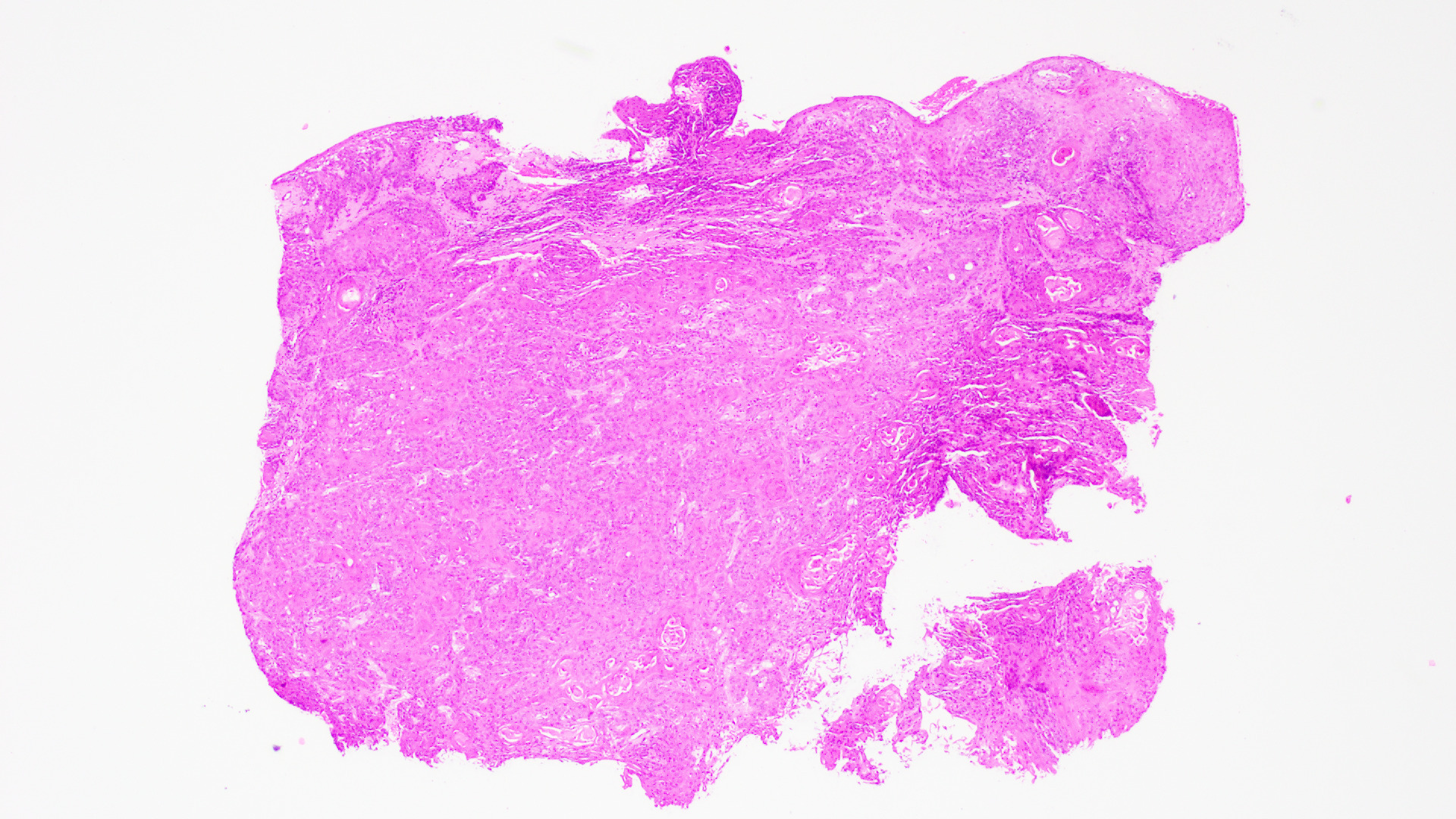

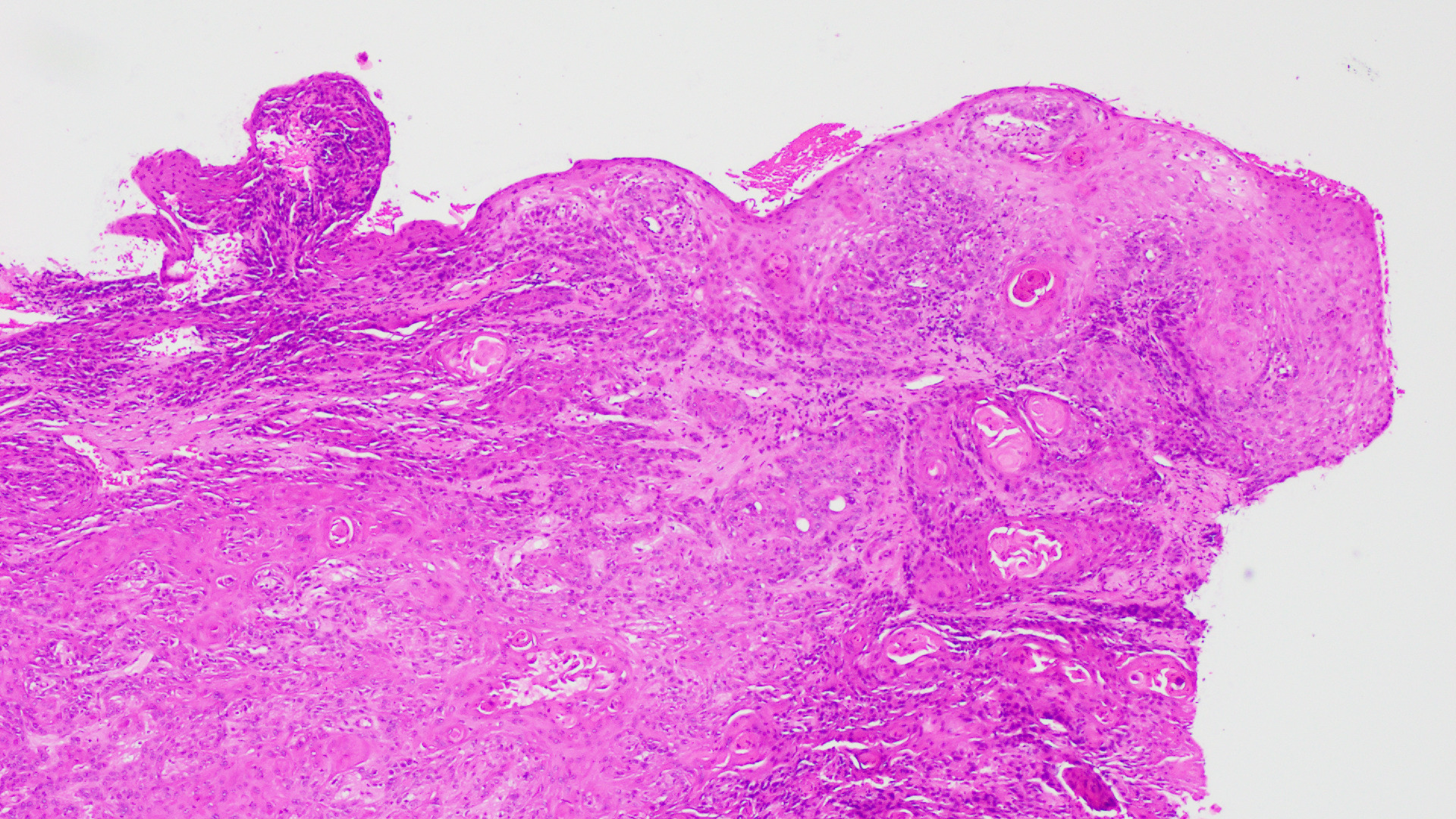

Weinberg D, Gomez-Martinez RA. Vulvar Cancer. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2019 Mar:46(1):125-135. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.09.008. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30683259]

[6]

Faber MT, Sand FL, Albieri V, Norrild B, Kjaer SK, Verdoodt F. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in squamous cell carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva. International journal of cancer. 2017 Sep 15:141(6):1161-1169. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30821. Epub 2017 Jun 21

[PubMed PMID: 28577297]

[7]

Zhang J, Zhang Y, Zhang Z. Prevalence of human papillomavirus and its prognostic value in vulvar cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2018:13(9):e0204162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204162. Epub 2018 Sep 26

[PubMed PMID: 30256833]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[8]

Clancy AA, Spaans JN, Weberpals JI. The forgotten woman's cancer: vulvar squamous cell carcinoma (VSCC) and a targeted approach to therapy. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2016 Sep:27(9):1696-705. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw242. Epub 2016 Jun 20

[PubMed PMID: 27329249]

[9]

Allbritton JI. Vulvar Neoplasms, Benign and Malignant. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2017 Sep:44(3):339-352. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2017.04.002. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28778635]

[10]

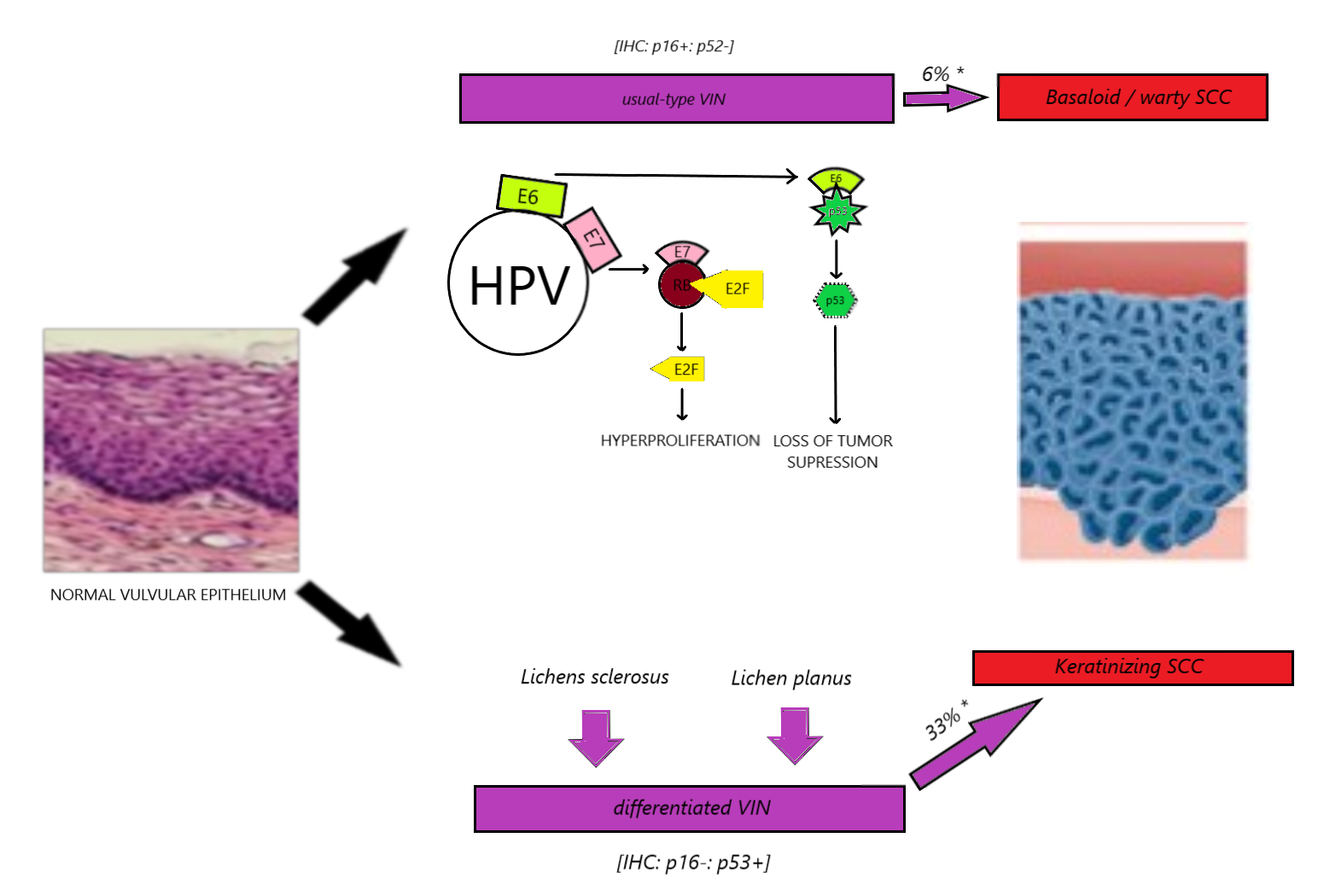

Bornstein J, Bogliatto F, Haefner HK, Stockdale CK, Preti M, Bohl TG, Reutter J, ISSVD Terminology Committee. The 2015 International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) Terminology of Vulvar Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2016 Jan:20(1):11-4. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000169. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26704327]

[11]

Tan A, Bieber AK, Stein JA, Pomeranz MK. Diagnosis and management of vulvar cancer: A review. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Dec:81(6):1387-1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.055. Epub 2019 Jul 23

[PubMed PMID: 31349045]

[12]

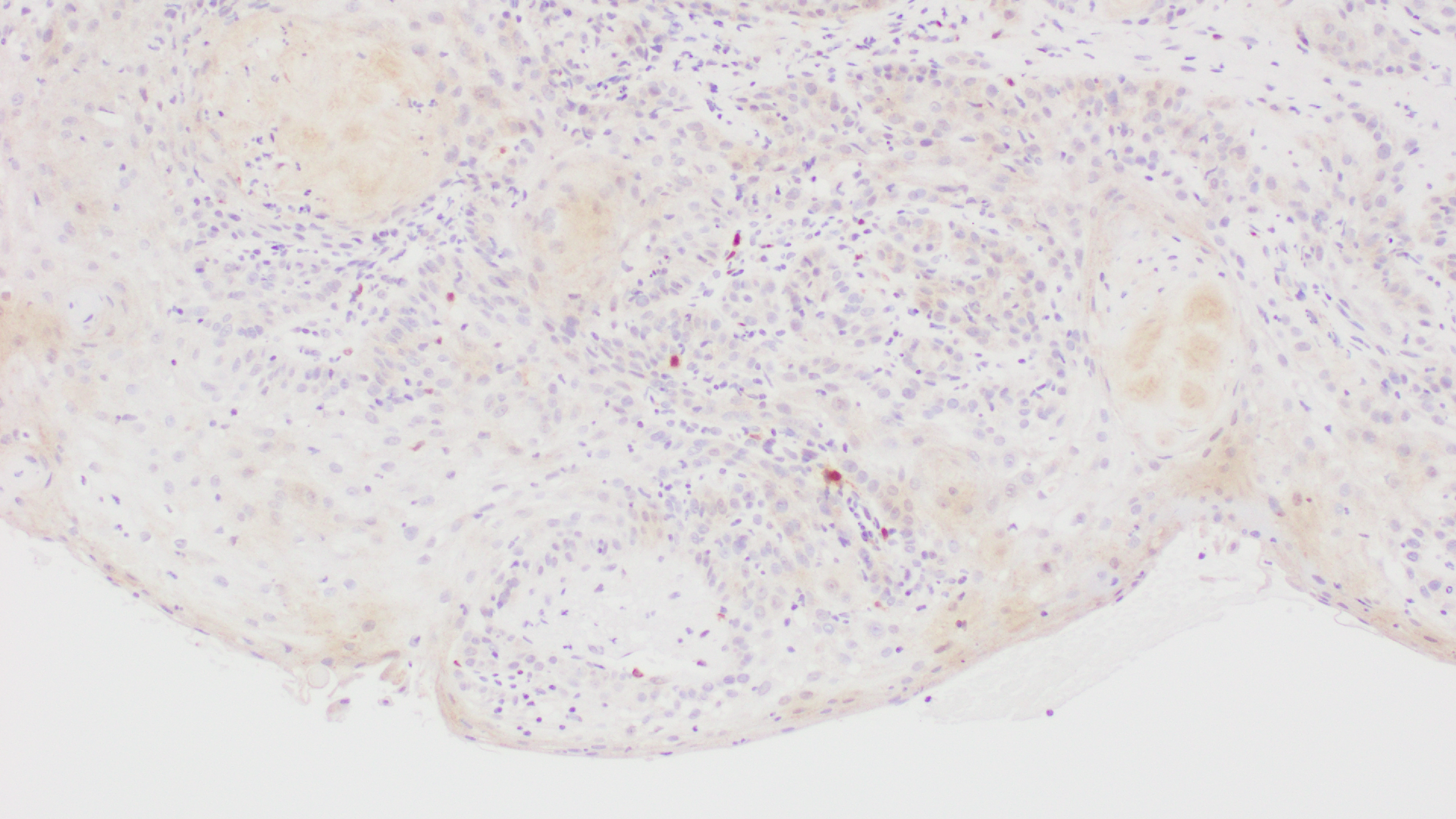

Dasgupta S, Ewing-Graham PC, Swagemakers SMA, van der Spek PJ, van Doorn HC, Noordhoek Hegt V, Koljenović S, van Kemenade FJ. Precursor lesions of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma - histology and biomarkers: A systematic review. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2020 Mar:147():102866. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102866. Epub 2020 Jan 15

[PubMed PMID: 32058913]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[13]

Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, Boveri S, Di Pumpo O, Privitera SS, Ghiringhello B, Benedetto C. Vulvar Lichen Sclerosus and Neoplastic Transformation: A Retrospective Study of 976 Cases. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2016 Apr:20(2):180-3. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000186. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26882123]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[14]

Schuurman MS, van den Einden LC, Massuger LF, Kiemeney LA, van der Aa MA, de Hullu JA. Trends in incidence and survival of Dutch women with vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990). 2013 Dec:49(18):3872-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.003. Epub 2013 Sep 3

[PubMed PMID: 24011936]

[15]

Sinha K, Abdul-Wahab A, Calonje E, Craythorne E, Lewis FM. Basal cell carcinoma of the vulva: treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2019 Aug:44(6):651-653. doi: 10.1111/ced.13881. Epub 2019 Jan 7

[PubMed PMID: 30618159]

[16]

Chanda JJ. Extramammary Paget's disease: prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1985 Dec:13(6):1009-14

[PubMed PMID: 3001158]

[17]

Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget's disease. Journal of clinical pathology. 2000 Oct:53(10):742-9

[PubMed PMID: 11064666]

[18]

Jones IS, Crandon A, Sanday K. Paget's disease of the vulva: Diagnosis and follow-up key to management; a retrospective study of 50 cases from Queensland. Gynecologic oncology. 2011 Jul:122(1):42-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.033. Epub 2011 Apr 17

[PubMed PMID: 21501860]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[19]

Parker LP, Parker JR, Bodurka-Bevers D, Deavers M, Bevers MW, Shen-Gunther J, Gershenson DM. Paget's disease of the vulva: pathology, pattern of involvement, and prognosis. Gynecologic oncology. 2000 Apr:77(1):183-9

[PubMed PMID: 10739709]

[20]

St Claire K, Hoover A, Ashack K, Khachemoune A. Extramammary Paget disease. Dermatology online journal. 2019 Apr 15:25(4):. pii: 13030/qt7qg8g292. Epub 2019 Apr 15

[PubMed PMID: 31046904]

[21]

Cai Y, Sheng W, Xiang L, Wu X, Yang H. Primary extramammary Paget's disease of the vulva: the clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes in a series of 43 patients. Gynecologic oncology. 2013 May:129(2):412-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.029. Epub 2013 Feb 27

[PubMed PMID: 23454498]

[22]

Konstantinova AM, Shelekhova KV, Stewart CJ, Spagnolo DV, Kutzner H, Kacerovska D, Plaza JA, Suster S, Bouda J, Pavlovsky M, Kyrpychova L, Michal M, Guenova E, Kazakov DV. Depth and Patterns of Adnexal Involvement in Primary Extramammary (Anogenital) Paget Disease: A Study of 178 Lesions From 146 Patients. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2016 Nov:38(11):802-808

[PubMed PMID: 26863064]

[23]

Ragnarsson-Olding BK, Nilsson BR, Kanter-Lewensohn LR, Lagerlöf B, Ringborg UK. Malignant melanoma of the vulva in a nationwide, 25-year study of 219 Swedish females: predictors of survival. Cancer. 1999 Oct 1:86(7):1285-93

[PubMed PMID: 10506715]

[24]

Rouzbahman M, Kamel-Reid S, Al Habeeb A, Butler M, Dodge J, Laframboise S, Murphy J, Rasty G, Ghazarian D. Malignant Melanoma of Vulva and Vagina: A Histomorphological Review and Mutation Analysis--A Single-Center Study. Journal of lower genital tract disease. 2015 Oct:19(4):350-3. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000142. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26225944]

[25]

Hou JY, Baptiste C, Hombalegowda RB, Tergas AI, Feldman R, Jones NL, Chatterjee-Paer S, Bus-Kwolfski A, Wright JD, Burke WM. Vulvar and vaginal melanoma: A unique subclass of mucosal melanoma based on a comprehensive molecular analysis of 51 cases compared with 2253 cases of nongynecologic melanoma. Cancer. 2017 Apr 15:123(8):1333-1344. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30473. Epub 2016 Dec 27

[PubMed PMID: 28026870]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[26]

Phillips GL, Bundy BN, Okagaki T, Kucera PR, Stehman FB. Malignant melanoma of the vulva treated by radical hemivulvectomy. A prospective study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Cancer. 1994 May 15:73(10):2626-32

[PubMed PMID: 8174062]

[27]

Leitao MM Jr. Management of vulvar and vaginal melanomas: current and future strategies. American Society of Clinical Oncology educational book. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Annual Meeting. 2014:():e277-81. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.e277. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24857113]

[28]

Nascimento AF, Granter SR, Cviko A, Yuan L, Hecht JL, Crum CP. Vulvar acanthosis with altered differentiation: a precursor to verrucous carcinoma? The American journal of surgical pathology. 2004 May:28(5):638-43

[PubMed PMID: 15105653]

[29]

Chen H, Gonzalez JL, Brennick JB, Liu M, Yan S. Immunohistochemical patterns of ProEx C in vulvar squamous lesions: detection of overexpression of MCM2 and TOP2A. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2010 Sep:34(9):1250-7. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ecf829. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20697251]

[30]

Gualco M, Bonin S, Foglia G, Fulcheri E, Odicino F, Prefumo F, Stanta G, Ragni N. Morphologic and biologic studies on ten cases of verrucous carcinoma of the vulva supporting the theory of a discrete clinico-pathologic entity. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2003 May-Jun:13(3):317-24

[PubMed PMID: 12801263]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[31]

Aartsen EJ, Albus-Lutter CE. Vulvar sarcoma: clinical implications. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 1994 Sep:56(3):181-9

[PubMed PMID: 7821491]

[32]

Nguyen AH, Detty SQ, Gonzaga MI, Huerter C. Clinical Features and Treatment of Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans Affecting the Vulva: A Literature Review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2017 Jun:43(6):771-774. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001113. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 28323651]

[33]

Iavazzo C, Gkegkes ID, Vrachnis N. Dilemmas in the management of patients with vulval epithelioid sarcoma: a literature review. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2014 May:176():1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.02.013. Epub 2014 Feb 20

[PubMed PMID: 24636595]

[34]

Bhalwal AB, Nick AM, Dos Reis R, Chen CL, Munsell MF, Ramalingam P, Salcedo MP, Ramirez PT, Sood AK, Schmeler KM. Carcinoma of the Bartholin Gland: A Review of 33 Cases. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2016 May:26(4):785-9. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000656. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26844611]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[35]

Nazeran T, Cheng AS, Karnezis AN, Tinker AV, Gilks CB. Bartholin Gland Carcinoma: Clinicopathologic Features, Including p16 Expression and Clinical Outcome. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists. 2019 Mar:38(2):189-195. doi: 10.1097/PGP.0000000000000489. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29406447]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[36]

Edwards L. Pigmented vulvar lesions. Dermatologic therapy. 2010 Sep-Oct:23(5):449-57. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2010.01349.x. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 20868400]

[37]

Koh WJ, Greer BE, Abu-Rustum NR, Campos SM, Cho KR, Chon HS, Chu C, Cohn D, Crispens MA, Dizon DS, Dorigo O, Eifel PJ, Fisher CM, Frederick P, Gaffney DK, Han E, Higgins S, Huh WK, Lurain JR 3rd, Mariani A, Mutch D, Nagel C, Nekhlyudov L, Fader AN, Remmenga SW, Reynolds RK, Tillmanns T, Ueda S, Valea FA, Wyse E, Yashar CM, McMillian N, Scavone J. Vulvar Cancer, Version 1.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2017 Jan:15(1):92-120

[PubMed PMID: 28040721]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[38]

Rigel DS, Carucci JA. Malignant melanoma: prevention, early detection, and treatment in the 21st century. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2000 Jul-Aug:50(4):215-36; quiz 237-40

[PubMed PMID: 10986965]

[39]

Schmitt AR, Long BJ, Weaver AL, McGree ME, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Brewer JD, Cliby WA. Evidence-Based Screening Recommendations for Occult Cancers in the Setting of Newly Diagnosed Extramammary Paget Disease. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2018 Jul:93(7):877-883. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.02.024. Epub 2018 May 24

[PubMed PMID: 29804724]

[40]

Ansink A, van der Velden J. Surgical interventions for early squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2000:2000(2):CD002036

[PubMed PMID: 10796849]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[41]

Maggino T, Landoni F, Sartori E, Zola P, Gadducci A, Alessi C, Soldà M, Coscio S, Spinetti G, Maneo A, Ferrero A, Konishi De Toffoli G. Patterns of recurrence in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. A multicenter CTF Study. Cancer. 2000 Jul 1:89(1):116-22

[PubMed PMID: 10897008]

[42]

McCann GA, Taege SK, Boutsicaris CE, Phillips GS, Eisenhauer EL, Fowler JM, O'Malley DM, Copeland LJ, Cohn DE, Salani R. The impact of close surgical margins after radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2013 Jan:128(1):44-48. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.10.028. Epub 2012 Nov 5

[PubMed PMID: 23138134]

[43]

Ang C, Bryant A, Barton DP, Pomel C, Naik R. Exenterative surgery for recurrent gynaecological malignancies. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Feb 4:2014(2):CD010449. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010449.pub2. Epub 2014 Feb 4

[PubMed PMID: 24497188]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[44]

Zhang W, Wang Y, Chen W, Du J, Xiang L, Ye S, Yang H. Verrucous Carcinoma of the Vulva: A Case Report and Literature Review. The American journal of case reports. 2019 Apr 19:20():551-556. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.914367. Epub 2019 Apr 19

[PubMed PMID: 31002657]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[45]

Long B, Schmitt AR, Weaver AL, McGree M, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Brewer J, Cliby WA. A matter of margins: Surgical and pathologic risk factors for recurrence in extramammary Paget's disease. Gynecologic oncology. 2017 Nov:147(2):358-363. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.09.008. Epub 2017 Sep 19

[PubMed PMID: 28935274]

[46]

Stehman FB, Bundy BN, Ball H, Clarke-Pearson DL. Sites of failure and times to failure in carcinoma of the vulva treated conservatively: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1996 Apr:174(4):1128-32; discussion 1132-3

[PubMed PMID: 8623839]

[47]

Wills A, Obermair A. A review of complications associated with the surgical treatment of vulvar cancer. Gynecologic oncology. 2013 Nov:131(2):467-79. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.07.082. Epub 2013 Jul 14

[PubMed PMID: 23863358]

[48]

Lawrie TA, Patel A, Martin-Hirsch PP, Bryant A, Ratnavelu ND, Naik R, Ralte A. Sentinel node assessment for diagnosis of groin lymph node involvement in vulval cancer. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Jun 27:2014(6):CD010409. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010409.pub2. Epub 2014 Jun 27

[PubMed PMID: 24970683]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[49]

Huang J, Yu N, Wang X, Long X. Incidence of lower limb lymphedema after vulvar cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017 Nov:96(46):e8722. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008722. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29145314]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[50]

Skanjeti A, Dhomps A, Paschetta C, Tordo J, Giammarile F. Sentinel Node Mapping in Gynecologic Cancers: A Comprehensive Review. Seminars in nuclear medicine. 2019 Nov:49(6):521-533. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2019.06.012. Epub 2019 Jun 29

[PubMed PMID: 31630736]

[51]

de Hullu JA, van der Zee AG. Surgery and radiotherapy in vulvar cancer. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2006 Oct:60(1):38-58

[PubMed PMID: 16829120]

[52]

Levenback CF, Ali S, Coleman RL, Gold MA, Fowler JM, Judson PL, Bell MC, De Geest K, Spirtos NM, Potkul RK, Leitao MM Jr, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Rossi EC, Lentz SS, Burke JJ 2nd, Van Le L, Trimble CL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in women with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a gynecologic oncology group study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Nov 1:30(31):3786-91. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2528. Epub 2012 Jul 2

[PubMed PMID: 22753905]

[53]

Covens A, Vella ET, Kennedy EB, Reade CJ, Jimenez W, Le T. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in vulvar cancer: Systematic review, meta-analysis and guideline recommendations. Gynecologic oncology. 2015 May:137(2):351-61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.02.014. Epub 2015 Feb 20

[PubMed PMID: 25703673]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[54]

Gill BS, Bernard ME, Lin JF, Balasubramani GK, Rajagopalan MS, Sukumvanich P, Krivak TC, Olawaiye AB, Kelley JL, Beriwal S. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy with radiation for node-positive vulvar cancer: A National Cancer Data Base (NCDB) analysis. Gynecologic oncology. 2015 Jun:137(3):365-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.056. Epub 2015 Apr 11

[PubMed PMID: 25868965]

[55]

Mahner S, Jueckstock J, Hilpert F, Neuser P, Harter P, de Gregorio N, Hasenburg A, Sehouli J, Habermann A, Hillemanns P, Fuerst S, Strauss HG, Baumann K, Thiel F, Mustea A, Meier W, du Bois A, Griebel LF, Woelber L, AGO-CaRE 1 investigators. Adjuvant therapy in lymph node-positive vulvar cancer: the AGO-CaRE-1 study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2015 Mar:107(3):. pii: dju426. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju426. Epub 2015 Jan 24

[PubMed PMID: 25618900]

[56]

Ignatov T, Eggemann H, Burger E, Costa SD, Ignatov A. Adjuvant radiotherapy for vulvar cancer with close or positive surgical margins. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2016 Feb:142(2):489-95

[PubMed PMID: 26498775]

[57]

Montana GS, Thomas GM, Moore DH, Saxer A, Mangan CE, Lentz SS, Averette HE. Preoperative chemo-radiation for carcinoma of the vulva with N2/N3 nodes: a gynecologic oncology group study. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2000 Nov 1:48(4):1007-13

[PubMed PMID: 11072157]

[58]

Moore DH, Thomas GM, Montana GS, Saxer A, Gallup DG, Olt G. Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1998 Aug 1:42(1):79-85

[PubMed PMID: 9747823]

[59]

Moore DH, Ali S, Koh WJ, Michael H, Barnes MN, McCourt CK, Homesley HD, Walker JL. A phase II trial of radiation therapy and weekly cisplatin chemotherapy for the treatment of locally-advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva: a gynecologic oncology group study. Gynecologic oncology. 2012 Mar:124(3):529-33. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.003. Epub 2011 Nov 9

[PubMed PMID: 22079361]

[60]

Tagliaferri L, Casà C, Macchia G, Pesce A, Garganese G, Gui B, Perotti G, Gentileschi S, Inzani F, Autorino R, Cammelli S, Morganti AG, Valentini V, Gambacorta MA. The Role of Radiotherapy in Extramammary Paget Disease: A Systematic Review. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2018 May:28(4):829-839. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001237. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29538255]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[61]

Zhang R, Wang L. Photodynamic therapy for treatment of usual-type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia: a case report and literature review. The Journal of international medical research. 2019 Aug:47(8):4019-4026. doi: 10.1177/0300060519862940. Epub 2019 Jul 31

[PubMed PMID: 31364444]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[62]

Horowitz NS, Olawaiye AB, Borger DR, Growdon WB, Krasner CN, Matulonis UA, Liu JF, Lee J, Brard L, Dizon DS. Phase II trial of erlotinib in women with squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva. Gynecologic oncology. 2012 Oct:127(1):141-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.028. Epub 2012 Jun 26

[PubMed PMID: 22750258]

[63]

Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, Guminski A, Hauschild A, Lewis KD, Chung CH, Hernandez-Aya L, Lim AM, Chang ALS, Rabinowits G, Thai AA, Dunn LA, Hughes BGM, Khushalani NI, Modi B, Schadendorf D, Gao B, Seebach F, Li S, Li J, Mathias M, Booth J, Mohan K, Stankevich E, Babiker HM, Brana I, Gil-Martin M, Homsi J, Johnson ML, Moreno V, Niu J, Owonikoko TK, Papadopoulos KP, Yancopoulos GD, Lowy I, Fury MG. PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2018 Jul 26:379(4):341-351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1805131. Epub 2018 Jun 4

[PubMed PMID: 29863979]

[64]

Terlou A, van Seters M, Kleinjan A, Heijmans-Antonissen C, Santegoets LA, Beckmann I, van Beurden M, Helmerhorst TJ, Blok LJ. Imiquimod-induced clearance of HPV is associated with normalization of immune cell counts in usual type vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia. International journal of cancer. 2010 Dec 15:127(12):2831-40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25302. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 21351262]

[65]

Wan MT, Ming ME. Nivolumab versus ipilimumab in the treatment of advanced melanoma: a critical appraisal: ORIGINAL ARTICLE: Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R et al. Overall survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017; 377:1345-56. The British journal of dermatology. 2018 Aug:179(2):296-300. doi: 10.1111/bjd.16785. Epub 2018 Jun 5

[PubMed PMID: 29766492]

[66]

van der Linden M, Meeuwis K, van Hees C, van Dorst E, Bulten J, Bosse T, IntHout J, Boll D, Slangen B, van Seters M, van Beurden M, van Poelgeest M, de Hullu J. The Paget Trial: A Multicenter, Observational Cohort Intervention Study for the Clinical Efficacy, Safety, and Immunological Response of Topical 5% Imiquimod Cream for Vulvar Paget Disease. JMIR research protocols. 2017 Sep 6:6(9):e178. doi: 10.2196/resprot.7503. Epub 2017 Sep 6

[PubMed PMID: 28877863]

[67]

Edey KA, Allan E, Murdoch JB, Cooper S, Bryant A. Interventions for the treatment of Paget's disease of the vulva. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2019 Jun 5:6(6):CD009245. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009245.pub3. Epub 2019 Jun 5

[PubMed PMID: 31167037]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[68]

Te Grootenhuis NC, van der Zee AG, van Doorn HC, van der Velden J, Vergote I, Zanagnolo V, Baldwin PJ, Gaarenstroom KN, van Dorst EB, Trum JW, Slangen BF, Runnebaum IB, Tamussino K, Hermans RH, Provencher DM, de Bock GH, de Hullu JA, Oonk MH. Sentinel nodes in vulvar cancer: Long-term follow-up of the GROningen INternational Study on Sentinel nodes in Vulvar cancer (GROINSS-V) I. Gynecologic oncology. 2016 Jan:140(1):8-14. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.09.077. Epub 2015 Sep 30

[PubMed PMID: 26428940]

[69]

Canlorbe G, Rouzier R, Bendifallah S, Chéreau E. [Impact of sentinel node technique on the survival in patients with vulvar cancer: analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database]. Gynecologie, obstetrique & fertilite. 2012 Nov:40(11):647-51. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2012.07.014. Epub 2012 Sep 15

[PubMed PMID: 22985904]

[70]

Heinzelmann-Schwarz VA, Nixdorf S, Valadan M, Diczbalis M, Olivier J, Otton G, Fedier A, Hacker NF, Scurry JP. A clinicopathological review of 33 patients with vulvar melanoma identifies c-KIT as a prognostic marker. International journal of molecular medicine. 2014 Apr:33(4):784-94. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1659. Epub 2014 Feb 14

[PubMed PMID: 24535703]

[71]

Scheistrøen M, Tropé C, Koern J, Pettersen EO, Abeler VM, Kristensen GB. Malignant melanoma of the vulva. Evaluation of prognostic factors with emphasis on DNA ploidy in 75 patients. Cancer. 1995 Jan 1:75(1):72-80

[PubMed PMID: 7804980]

[72]

Iacoponi S, Rubio P, Garcia E, Oehler MK, Diez J, Diaz-De la Noval B, Mora P, Gardella B, Gomez I, Kotsopoulos IC, Zalewski K, Zapardiel I, VULCAN Study collaborative group. Prognostic Factors of Recurrence and Survival in Vulvar Melanoma: Subgroup Analysis of the VULvar CANcer Study. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society. 2016 Sep:26(7):1307-12. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000768. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27465889]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[73]

Rasmussen CL, Sand FL, Hoffmann Frederiksen M, Kaae Andersen K, Kjaer SK. Does HPV status influence survival after vulvar cancer? International journal of cancer. 2018 Mar 15:142(6):1158-1165. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31139. Epub 2017 Nov 16

[PubMed PMID: 29090456]

[74]

Nooij LS, Brand FA, Gaarenstroom KN, Creutzberg CL, de Hullu JA, van Poelgeest MI. Risk factors and treatment for recurrent vulvar squamous cell carcinoma. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2016 Oct:106():1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.07.007. Epub 2016 Jul 25

[PubMed PMID: 27637349]

[75]

Salani R, Khanna N, Frimer M, Bristow RE, Chen LM. An update on post-treatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) recommendations. Gynecologic oncology. 2017 Jul:146(1):3-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.03.022. Epub 2017 Mar 31

[PubMed PMID: 28372871]

[76]

Bryan S, Barbara C, Thomas J, Olaitan A. HPV vaccine in the treatment of usual type vulval and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic review. BMC women's health. 2019 Jan 7:19(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0707-9. Epub 2019 Jan 7

[PubMed PMID: 30616555]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence