Continuing Education Activity

Human toxocariasis is a helminth infection that primarily impacts individuals of lower socioeconomic class in tropical and subtropical regions around the world. Toxocariasis is a roundworm, also known as nematode, that rarely causes clinical problems. However, it does have the potential to cause blindness or meningoencephalitis. Two main species of Toxocara affect humans: Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati. Hosts include cats, dogs, foxes, coyotes, and wolves. These hosts harbor the nematodes in their guts, shedding the eggs in their feces. The embryonated eggs remain infectious for years outside the host. In the wild, carnivorous animals such as cats and dogs consume infected meat or simply soil containing the eggs, and the parasite persists in their gut. Additionally, transplacental transmission has been documented in dogs and cats. Humans are amongst a plethora of possible intermediate hosts. Clinical disease results from the migration of the parasite through extraintestinal tissue. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of Toxocara canis and highlights the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance patient outcomes.

Objectives:

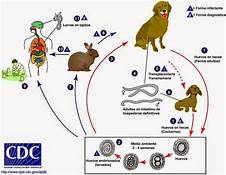

- Explain the life cycle of Toxocara canis.

- Outline the organ systems most commonly affected by Toxocara canis.

- Describe when the diagnosis of Toxocara canis should be considered.

- Review the importance of enhancing care coordination among the interprofessional team to ensure proper evaluation and management of Toxocara canis

Introduction

Human toxocariasis is a helminthic infection that primarily impacts populations of lower socioeconomic class in tropical and subtropical latitudes around the world. It is a roundworm (also known as nematode) that is not frequently clinically consequential; however, it is known to have severe complications such as blindness or meningoencephalitis.

Two main species of Toxocara affect humans: Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati. Definite hosts include cats, dogs, foxes, coyotes, and wolves. These hosts harbor the nematodes in their gut, shedding eggs in their feces. These embryonated eggs remain infectious for years outside the definitive host. In the wild, intermediate hosts such as other cats, dogs, rabbits, and fowl ingest the cysts, which hatch and migrate to various muscles and organs to encyst. In the wild, carnivorous animals such as cats and dogs consume infected meat (or simply soil containing the eggs), and the parasite remains in their gut. Additionally, there is solid documentation of transplacental transmission in dogs and cats. Humans are amongst a plethora of possible intermediate animal hosts. Clinical disease results from the migration of the parasite through extra-intestinal tissues.[1][2]

Visceral larva migrans usually occurs in children because they often play in areas of contaminated soil.

Etiology

Clinical Toxocariasis is a product of Toxocara species migration through tissues. Toxocara canis primarily infects canids (dogs, foxes, and wolves), whereas T. cati primarily infects felids (cats). T. cati is thought to more frequently cause severe human disease. Children are more prone to infection via the fecal-oral route as they are more likely to consume Toxocara eggs by ingesting soil or other contaminated substances. Epidemiologic studies have found that public parks with community sandboxes have particularly high egg burdens, placing children frequenting these areas at risk.[3]

Epidemiology

Toxocara species are prevalent worldwide — their concentration is in areas with large populations of domestic dogs and cats. Worldwide, Toxocara predominantly affects children in tropical and subtropical regions. Globally, the disease is more common in developing countries, with seroprevalence reported above 80% in children in parts of Nigeria.[4] In the United States, the seroprevalence estimates range from 5 to 15%, and approximately 10000 clinical cases are diagnosed yearly.[5][6] Risk factors for disease contraction include poverty, latitude, contaminated soil, young age, and high concentration of dogs and cats. There is a large discrepancy in prevalence between the developed and developing world just due to these risk factors.

Pathophysiology

Clinical disease is due to parasitic nematode larva migration through tissues. The signs and symptoms differ based on the affected organ and the host inflammatory response. There are four types of disease: ocular larva migrans (OLM), visceral larva migrans (VLM), neurotoxocariasis, and covert toxocariasis. The covert disease most often presents with simple, persistent eosinophilia and may be attributed to the continuation of the migratory phase. Interestingly, this migratory phase may last for years.[7]

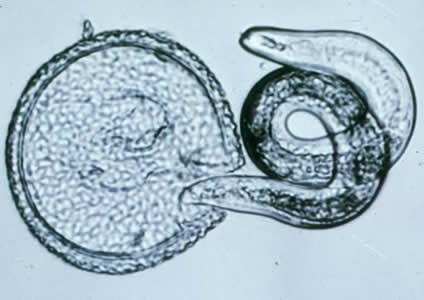

The larva often accumulate in organs but are not able to complete the life cycle in humans. In the organs, the larva incite a granulomatous reaction or an abscess.

History and Physical

Ocular larva migrans (OLM) is caused by larval migration through the posterior segment of the eye and is a leading infectious cause of blindness in children in developed countries. OLM classically presents with unilateral vision loss in a child, most often between the ages of five to ten. The exam may demonstrate uveitis, retinitis, choroiditis, or endophthalmitis based on the location of the parasite. The infection can also result in secondary glaucoma. Histologically, eosinophilic abscesses with surrounding granulomatous reactions are the expected manifestations.

Visceral larva migrans (VLM) is caused by larval migration through both solid and hollow organs in the abdomen and should be considered in any child presenting with fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and eosinophilia. An exam may be notable for hepatosplenomegaly, which can serve as a clue for clinicians that the presentation is not simple viral gastroenteritis. Lung involvement can result in bronchospasm and wheezing.

Central nervous system disease is rare but can be severe and range from eosinophilic meningitis to fulminant meningoencephalitis, presenting with seizures, encephalopathy, or neuropsychiatric symptoms.[7][8]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of toxocariasis is difficult. While identification of the organism on microscopy is the gold standard, it is rarely achieved for practical reasons. ELISA assays are available and recommended; yet, they, unfortunately, have relatively poor sensitivity (approximately 80%).[9] Additionally, given that humans are not definitive hosts for Toxocara, stool microscopy is ineffective. Other secondary indicators of infection include eosinophilia and hypergammaglobulinemia. However, these markers are not specific, and their sensitivities do not have extensive backing in the literature. Clinical diagnosis and presumptive treatment is an option to consider in the right clinical context.

Treatment / Management

For the treatment of VLM, albendazole and mebendazole both are effective. Albendazole is recommended as it has superior tissue penetration than mebendazole. The dose of albendazole is 10 mg/kg/day divided into two doses for five days. Depending on other endemic infections, ivermectin and DEC (diethylcarbamazine) may be useful as well. Treatment of OLM is more difficult and revolves around decreasing inflammation. Thus, prednisone is often an addition to antihelminthic agents, and surgery is reserved for only the most severe cases.[7][9]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for VLM is broad as many infections may cause eosinophilia and fever. As this is a global disease, local epidemiology is paramount. Considerations include Ascariasis (Löffler syndrome), trichinosis, Strongyloides, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis, Paragonimus, Entamoeba histolytica, and Fasciola hepatica.

The central differential for OLM is retinoblastoma. The disease was originally discovered in the 1950s in enucleated eyes suspected to have retinoblastoma.

Eosinophilic meningitis has a narrow differential diagnosis as well: Angiostrongylus (rat-lung worm) is the chief consideration.

Prognosis

The prognosis for VLM is generally good; however, chronic disease has potential correlations with both epilepsy and cognitive delay. Some children may develop loss of vision. Other complications reported include myocarditis, pneumonia, and Henoch Schönlein purpura.

Complications

Per above, complications, while rare, include blindness, severe neurologic disease, and even death.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Given that toxocariasis spreads via the fecal-oral route, patient education in hand hygiene is vital in risk factor modification. Also, patients should receive instruction on other risk factors such as exposure to pets and places where animal feces are present such as sandboxes. Common pitfalls amongst healthcare providers include failure to consider this diagnosis in children. The true disease burden is likely underestimated, and while failure to diagnose VLM may not carry acute complications, the chronic and economic burden of disease is likely profound.[3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of Toxocara is complicated as it is more than human disease and requires a One Health approach. Domestic animal carrier rates directly impact the risk of acquisition, vertical transmission is common in dogs and cats, and no vaccine exists. Thus, interprofessional collaboration is necessary for adequate control. The first challenge is increasing awareness. Toxocara is considered a neglected tropical infection, given the minimal level of research, funding, and publicity it receives despite carrying a significant disease burden. The role of the primary caregiver and nurse practitioner is invaluable in educating patients on preventing this parasitic infection.