Continuing Education Activity

Bacterial vaginosis is one of the most common vaginal infections affecting women worldwide, with significant implications for both reproductive and overall health. The condition stems from an imbalance in the vaginal microbiota, where typically dominant Lactobacillus species are overrun by organisms like Gardnerella. Bacterial vaginosis manifests as increased vaginal discharge with a distinct odor and extends beyond mere discomfort, with implications for both individual well-being and broader public health concerns. Despite its prevalence, misconceptions surrounding bacterial vaginosis persist, including its association with sexual transmission and optimal management strategies. Understanding its causes, symptoms, and diagnosis is crucial for an effective management strategy for bacterial vaginosis, underscoring the collaborative efforts of the healthcare team.

This course aims to thoroughly explore bacterial vaginosis, covering its microbiology, epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approaches, differential diagnosis, and evidence-based management strategies. Participants will gain the knowledge and skills necessary to effectively recognize, diagnose, and manage bacterial vaginosis in clinical practice, ultimately improving patient outcomes and quality of care.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of bacterial vaginosis.

Implement the proper evaluation of a patient with symptoms of bacterial vaginosis.

Select treatment and management plans available for bacterial vaginosis.

Collaborate with an interprofessional team to educate, treat, and monitor patients with bacterial vaginosis to improve patient outcomes.

Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis is a condition caused by an overgrowth of normal vaginal flora. Most commonly, this presents clinically with increased vaginal discharge that has a fish-like odor. The discharge itself is typically thin and either gray or white.[1] After being diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis, patients have an increased risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STI), and pregnant patients may have an increased risk of early delivery.[2][3][4] Previously, bacterial vaginosis was known as Gardnerella vaginitis, attributing the condition solely to Gardnerella bacteria. However, the term bacterial vaginosis, more accurately, acknowledges the potential overgrowth of various anaerobic bacteria in the vaginal ecosystem. This imbalance serves as the underlying cause of bacterial vaginosis. Renaming it bacterial vaginosis underscores the understanding that multiple bacteria naturally present in the vagina may proliferate excessively, leading to this condition.[5]

Etiology

Typically, bacterial vaginosis results from a reduction in hydrogen peroxide-producing lactobacilli in the vagina, coupled with an overgrowth of anaerobic bacteria.[6] However, the precise cause of bacterial vaginosis, stemming from the proliferation of Gardnerella and other anaerobic bacteria, remains elusive. While Gardnerella vaginalis is not typically considered contagious, the extent of its transmissibility remains unclear. Transmission of this bacterium through sexual activity could disrupt the natural vaginal bacterial balance. This imbalance creates an environment conducive to the excessive growth of opportunistic anaerobic bacteria, including G vaginalis, which potentially triggers bacterial vaginosis.[7][2]

Studies have detected G vaginalis in the vaginal tracts of up to 50% of asymptomatic women, suggesting it likely is a component of normal vaginal flora. Various factors may contribute to bacterial vaginosis development, including frequent bathing, douching, smoking, multiple sexual partners, use of over-the-counter intravaginal hygiene products, high stress levels, and increased frequency of sexual activity. G vaginalis transmission has been observed among females who have sex with females, potentially through direct mucous membrane contact or shared sex toys. A female with a female sexual partner has been shown to increase the risk of bacterial vaginosis by 60%.[6]

Epidemiology

Bacterial vaginosis is the most prevalent vaginitis in females of reproductive age, with an estimated occurrence ranging from 5% to 70%. The prevalence of bacterial vaginosis among females fluctuates from 20% to 60% across various countries. Worldwide, this condition is most common in parts of Africa and is found to be least common in Asia and Europe.[4] In the United States, bacterial vaginosis rates are approximately 30%.[8] Rates are variable between different ethnic groups and are most common in non-white women (51% in African American, 32% in Mexican American).[9][10] Bacterial vaginosis rates are lowest in Australia, New Zealand, and Western Europe.[11] In addition, bacterial vaginosis is more frequently encountered in females with multiple sexual partners, who are unmarried, who began to engage in intercourse at a young age, who are in commercial sex work, or who practice regular douching.[4][12] Due to this, douching is not recommended. Gardnerella has consistently been identified as a significant pathogen in bacterial vaginosis, possibly indicating a notable prevalence of Gardnerella in these populations.[13]

It is important to note that bacterial vaginosis is not currently considered an STI.[6] By definition, an STI is caused by a source that is not endogenous to the vaginal flora. Since an overgrowth of normal vaginal bacteria causes bacterial vaginosis, it does not meet the definition of an STI.[14] Furthermore, bacterial vaginosis can rarely be present in patients who have never had sexual intercourse.

Pathophysiology

Bacterial vaginosis is caused by an imbalance of the naturally occurring vaginal flora, characterized by both a change in the most common type of bacteria present as well as an increase in the total number of bacteria present. The Lactobacillus species dominates normal vaginal microbiota. Bacterial vaginosis is associated with a decline in the overall number of lactobacilli.[2] Although still uncertain, it is thought that most bacterial vaginosis infections start with Gardnerella vaginosis, which creates a biofilm that subsequently provides a conducive environment for the proliferation of other opportunistic bacteria.[15][16] G vaginalis also produces vaginolysin, a pore-forming toxin affecting human cells. Vaginolysin is a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin that initiates complex signaling cascades that trigger target cell lysis and enhance Gardnerella virulence.

Gardnerella has the necessary virulence factors that facilitate its adherence to host epithelial cells, enabling it to compete with Lactobacillus for dominance within the vaginal environment effectively. The symptoms of bacterial vaginosis are believed to arise from the proliferation of usually dormant vaginal anaerobes that establish symbiotic relationships with Gardnerella.[17] For approximately 40 years, G vaginalis stood as the only recognized species within the Gardnerella genus. More recently, as many as 13 new species have been identified, including G leopoldii, G piotii, and G swidsinskii.[18]

The association between bacterial vaginosis and an increased risk of acquiring future STIs stems from the fact that bacterial vaginosis allows other vaginal pathogens to gain access to the upper genital tract.[1] Bacterial vaginosis is also responsible for the presence of enzymes that reduce the ability of host leukocytes to fight infection and for an increased release of endotoxins that stimulate cytokine and prostaglandin production within the vagina.[1]

Histopathology

G vaginalis is a coccobacillus that lacks spore formation and motility.[19] This bacterium can be cultivated to form small, circular, gray colonies on both chocolate and human blood bilayer agar media with Tween 80 (HBT medium) agar. A selective medium for Gardnerella is colistin-oxolinic acid blood sugar. Although Gardnerella has a thin, gram-positive cell wall, it is regarded as gram-variable as its appearance can oscillate between gram-positive and gram-negative due to the fluctuating visibility of its thin cell wall.[20]

History and Physical

Most females with bacterial vaginosis present with a complaint of malodorous vaginal discharge.[14] Often, this symptom becomes more pronounced after sexual intercourse. Additional symptoms may include dysuria, dyspareunia, and vaginal pruritus; however, many affected individuals may be asymptomatic. The clinician should elicit a pertinent history regarding the risk factors for this condition and a history of bacterial vaginosis infections.[6] Some possible risk factors for bacterial vaginosis include vaginal douching, multiple sexual partners, recent antibiotic use, cigarette smoking, and the use of an intrauterine device.[3]

A proper physical exam should include a pelvic exam to note the characteristics of the vaginal discharge and to help exclude other similarly presenting diseases, including vaginal candidiasis, cervicitis, chlamydia, gonorrhea, herpes simplex virus, and trichomoniasis.[6] In addition, bacterial vaginosis itself is a risk factor for pelvic inflammatory disease, HIV, other STIs, and other obstetric disorders.[14] It is important to assess for fever, pelvic pain, and a history of STIs to rule out the more serious conditions that remain on the differential diagnosis.[6]

Cervical swabs may be sent to investigate the presence of chlamydia or gonorrhea infection. It is also important to assess for cervical friability and cervical motion tenderness. Self-collected swabs for bacterial vaginosis and swabs done without a speculum exam have proven unreliable and should be avoided. Likewise, culture, history alone, and pap smear are not reliable methods of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis and should be avoided.

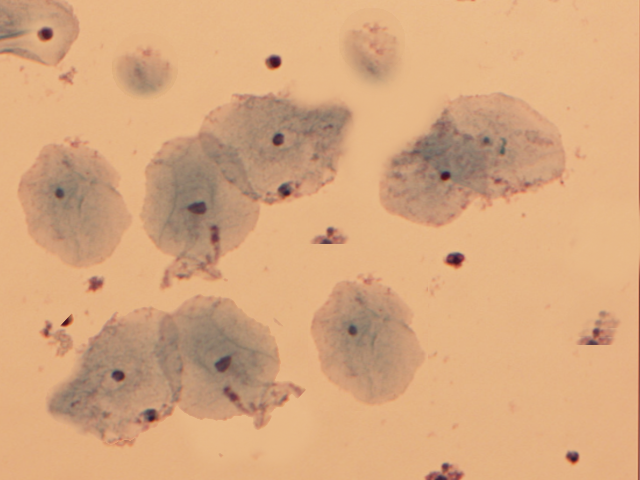

Since clue cells are a reliable diagnostic sign of bacterial vaginosis, the vaginal discharge can be examined under a microscope.[6] This diagnostic step can also help to rule out the presence of yeast or trichomonads.[14] It is important to note that many of these diseases can occur concomitantly, so it is necessary to scan the entire specimen for the presence of clue cells, even if another pathology is first identified. Testing the vaginal fluid pH can also assist in the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis.[6]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis is typically suggested clinically and confirmed by obtaining a swab of the vaginal discharge and creating a wet mount slide to view under a microscope. With bacterial vaginosis, the swab may demonstrate a higher than normal vaginal pH (>4.5), the presence of clue cells on a wet mount and a positive whiff test result. To determine the vaginal pH, pH paper can be utilized and compared to color controls. A drop of sodium chloride (NaCl) solution is placed on the wet mount slide to identify clue cells. The slide is covered with a cover slip and examined under the microscope to visualize the characteristic clue cells. Clue cells are epithelial cells of the cervix embedded with rod-shaped bacteria (see Image. Clue Cells).[14][17]

The whiff test is performed by adding a small amount of potassium hydroxide (KOH) to the microscopic slide containing the vaginal discharge. The whiff test result is positive if a characteristic fishy odor is revealed. Typically, 2 of these positive tests, in addition to the presence of the characteristic discharge, are enough to confirm the diagnosis of bacterial vaginosis.[21] If no discharge is present, all 3 of these criteria are needed to make the diagnosis.[1][22]

In clinical practice, bacterial vaginosis is often diagnosed using the Amsel criteria. At least 3 of the 4 findings are needed to confirm the diagnosis. The Amsel criteria include a thin white to yellow, homogenous discharge, clue cells on microscopy, pH of vaginal fluid >4.5, and the release of a fishy odor after adding an alkali solution (10% KOH) to the specimen. The modified Amsel criteria accept the presence of just 2 of the above factors, and research has shown that this is equally diagnostic. The sensitivity and specificity of the Amsel criteria are 70% and 94%, respectively.[21]

Alternatively, a gram stain of the vaginal fluid can be done to examine the predominant strain of bacteria. This technique is referred to as the Nugent process.[21] The Nugent scoring system employs a microscopic examination and gram-stain technique to evaluate the presence of vaginal bacteria, assigning a numerical score ranging from 0 to 10. A higher score indicates a more significant presence of bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis.[23] Nugent score is primarily utilized within the realm of research. Data have shown that this technique has a sensitivity and specificity of 89% and 83%, respectively, but it rarely is used in clinical practice.[22]

Amsel Criteria

Three out of 4 criteria must be present to diagnose bacterial vaginosis. Amsel criteria indicators that collectively aid in the accurate assessment of the condition include the following:

- Homogenous, thin, grayish-white vaginal discharge that coats the vaginal walls evenly

- Detection of ≥20% clue cells on a wet mount

- Vaginal pH >4.5

- Positive whiff test result

Generally, point-of-care tests are not commonly utilized in clinical settings due to their high cost. Instead, clinical practitioners often rely on commercial molecular diagnostic assays for assessment. These tests enable the quantification of bacteria and exhibit a sensitivity ranging from 90.5% to 96.7% and a specificity of 85.8% to 95%.[12] Since introducing the rapid identification method in 1982, isolating 91.4% of Gardnerella strains using a micro method involving starch, raffinose fermentation, and hippurate hydrolysis has become possible.[24]

Treatment / Management

Approximately 30% of bacterial vaginosis cases are known to resolve without treatment.[25] Treatment is not necessary for asymptomatic Gardnerella colonization.[23] Currently, insufficient evidence supports the notion that treating asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis reduces adverse patient outcomes. However, if a patient experiences distress due to the symptoms of bacterial vaginosis, it is recommended to pursue treatment using either oral or vaginal medication. Bacterial vaginosis can be treated with either clindamycin or metronidazole.[4] Both of these medications are effective if taken by mouth or applied vaginally. Both are safe to use in pregnant patients.[4] Initial treatment for bacterial vaginosis demonstrates notable efficacy, as cure rates within 1 month typically range from 80% to 90%.[11]

Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis may occur in as many as 80% of women within 9 months following initial treatment.[5][21][26] About 10% to 15% of females do not improve after the first course of antibiotics and may require additional treatment. If a patient experiences recurrent symptoms, a second course of antibiotics is generally prescribed.[5] A Cochrane review conducted in 2009 yielded tentative yet inconclusive evidence regarding the use of probiotics for treating and preventing bacterial vaginosis.[27] Importantly, it is worth noting that there is no universally established, strict definition for recurrent bacterial vaginosis.

Because bacterial vaginosis is not considered an STI, partners do not need to be treated, and there is no risk of passing the infection back and forth between partners.[14] A 2016 Cochrane review found high-quality evidence that treating the sexual partners of females with bacterial vaginosis did not affect symptoms, clinical outcomes, or the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis.[28][29][30]

Some studies have suggested that pregnant patients who are symptomatic from bacterial vaginosis should be treated before 22 weeks of gestation to reduce the risk of preterm labor. However, no clear consensus has been made on whether to screen for or treat bacterial vaginosis in the general population to prevent adverse outcomes such as preterm birth. To date, screening for bacterial vaginosis in asymptomatic females is not recommended, but testing and treatment of symptomatic females is indicated.[21]

In 2017, secnidazole was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for single-dose oral treatment for bacterial vaginosis.[23] Secnidazole, a next-generation 5-nitroimidazole, has a longstanding history of use in treating both parasitic and bacterial infections.[31]

In 2021, the FDA approved a single-dose clindamycin vaginal gel for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis in females aged 12 and older.[32][33][34] The addition of a single-dose therapy was applauded for its convenience of use and positive implications for patient compliance.[32]

Treatment Regimens for Bacterial Vaginosis

The treatment regimens used to treat bacterial vaginosis are as follows:

- Metronidazole: 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days

- Metronidazole 0.75% gel: 5 g intravaginally once daily for 5 days

- Clindamycin 2% cream: 5 g intravaginally nightly for 7 days

- Clindamycin 2% gel: 5 g intravaginally once only

Alternate Treatment Regimens for Bacterial Vaginosis

The alternative regimens for treating bacterial vaginosis are as follows:

- Clindamycin ovules: 100 mg ovule intravaginally every night for 3 days

- Clindamycin tablets: 300 mg orally twice daily for 7 days

- Tinidazole: 1 g orally every day for 5 days OR 2 g orally every day for 2 days

- Secnidazole granules: 2 g of oral granules all at once

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for bacterial vaginosis includes atrophic vaginitis, candidiasis, cervicitis, chlamydia, desquamative inflammatory vaginitis, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, and pelvic inflammatory disease. A proper physical exam can help narrow the differential diagnosis and exclude other similarly presenting diseases. A speculum exam can check for cervicitis, and a wet mount of the vaginal discharge can look for candidiasis or trichomoniasis. Additional cervical swabs can be collected to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea.[6]

Prognosis

Most uncomplicated cases of bacterial vaginosis resolve with treatment. However, recurrences are not uncommon due to the frequent failure of antibiotic treatment to restore the vagina to its typical Lactobacillus-dominant state. The biofilms of Gardnerella bacteria create a shield that helps prevent metronidazole from penetrating.[8] Within 3 months following treatment, approximately 80% of women may experience a recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. In the past decade, there has been a growing number of reports regarding bacterial vaginosis strains resistant to conventional treatments.

In a recent randomized controlled trial, a powder containing the naturally occurring live strain Lactobacillus crispatus CTV-05 was used. Following metronidazole treatment, women utilized the intravaginal powder to reduce the recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. The regimen involved using the powder 4 times daily during the first week, followed by twice-weekly use for 10 weeks. The use of lactobacilli powder after bacterial vaginosis treatment with metronidazole significantly lowered the recurrence rate of bacterial vaginosis up to 24 weeks after initial treatment. Notably, this approach has not yet received FDA approval.[35] Several alternative vaginal products are currently under investigation to decrease bacterial vaginosis recurrence rates.

Bacterial vaginosis has been associated with an increased risk of contracting STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas, herpes, human papillomavirus (HPV), and HIV. As Gardnerella damages the vaginal epithelium, it concurrently elevates the risk of HPV infection.[11] In addition, bacterial vaginosis may contribute to tubal infertility and difficulties in conceiving with assisted reproductive techniques, but a causal relationship has not yet been established.[23]

Intravaginal boric acid has also been recommended for managing recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Although this regimen lacks FDA approval, the existing evidence indicates the safety of intravaginal boric acid usage in non-pregnant females. The recommended dosage of intravaginal boric acid for women is 600 mg, administered intravaginally twice weekly to prevent bacterial vaginosis. The use of boric acid vaginal suppositories should be avoided during pregnancy, and it should not be taken orally.[25]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), multiple recurrences of bacterial vaginosis can be managed using any 1 of several treatment regimens.

Treatment for Recurrent Bacterial Vaginosis

- Metronidazole gel 0.75% OR metronidazole vaginal suppository 750 mg administered twice weekly for over 3 months

- Oral metronidazole or tinidazole 500 mg twice daily for 7 days, followed by 600 mg intravaginal boric acid daily for 21 days, followed by 0.75% metronidazole gel vaginally twice weekly for 4 to 6 months

- A monthly regimen involving oral administration of 2 g metronidazole taken concurrently with 150 mg oral fluconazole

Complications

Bacterial vaginosis can lead to various complications, underscoring the importance of timely diagnosis and management. The complications associated with bacterial vaginosis include the following:

- Increased risk of endometritis and salpingitis

- Increased risk of acquiring STIs

- Elevated risk of postsurgical infections

- Adverse pregnancy outcomes include premature labor, premature rupture of membranes, and postpartum endometritis

- Development of pelvic inflammatory disease

- Increased risk of neonatal meningitis

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and prevention strategies are crucial in mitigating the burden of bacterial vaginosis and its associated complications. Although the exact cause of the increased pH and bacterial overgrowth leading to bacterial vaginosis remains incompletely understood, there are preventive measures that women can adopt to minimize the overgrowth of G vaginalis and other non-lactobacilli. Healthcare providers should offer comprehensive education to women regarding the risk factors associated with bacterial vaginosis, which encompass, but are not limited to, engaging with multiple sexual partners, douching, lack of condom usage, smoking, and females having female sexual partners. Education on the importance of regular gynecological examinations and screening for bacterial vaginosis, particularly for high-risk populations and those with a history of recurrent infections, is essential for early detection and intervention. Implementing these preventive measures empowers individuals to take proactive steps in preserving vaginal health and reducing the incidence and recurrence of bacterial vaginosis while potentially contributing to lowering the acquisition of STIs and mitigating complications.

Pearls and Other Issues

Untreated bacterial vaginosis can lead to an increased risk of STIs, including HIV and pregnancy complications.[9] Bacterial vaginosis appears to increase the risk of subsequent chlamydia or gonorrhea infection by 1.9- and 1.8-fold, respectively. Research has shown that HIV-infected women found to have bacterial vaginosis are more likely to transmit HIV to their sexual partners than those without bacterial vaginosis.[9] Furthermore, bacterial vaginosis is associated with up to a 6-fold increase in HIV shedding.[9][36][10] Bacterial vaginosis is also a risk factor for herpes simplex virus type 2 infection and the increased risk of infection or reactivation of HPV. Recent literature has shown that bacterial vaginosis predicts HPV persistence, implying that treating even asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis in women with HPV coinfection may be warranted.

During pregnancy, bacterial vaginosis has been associated with a 2-fold increased risk of preterm delivery (particularly if bacterial vaginosis is diagnosed in the early second trimester) and a 3- to 5-fold increased risk of spontaneous abortion in pregnant females diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis in the first trimester. It has also been shown to increase the risk of chorioamnionitis, premature rupture of membranes, and postpartum endometritis. Data suggest an association between bacterial vaginosis and tubal factor infertility, and the prevalence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly higher in infertile females (45.5%) when compared to fertile females (15.4%). Studies have shown that women with bacterial vaginosis who later receive in vitro fertilization have a lower implantation rate and higher rates of early pregnancy loss.[7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bacterial vaginosis is a common genital tract overgrowth often encountered by emergency department physicians, family medicine clinicians, internists, and gynecologists. Bacterial vaginosis significantly diminishes the quality of life for affected women.[37]

Asymptomatic Gardnerella colonization does not necessitate treatment, as nearly 30% of cases resolve spontaneously. Physicians, advanced care practitioners, and nurses must know this caveat to prevent unnecessary antibiotic treatment. While all symptomatic patients require treatment, it is noteworthy that recurrences are prevalent. The recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is distressing, as it has been linked to unfavorable social, emotional, and sexual impacts.

Bacterial vaginosis maintains its economic strain on the healthcare system, necessitating multiple clinic visits and recurrent antibiotic utilization for affected patients.[35] Although bacterial vaginosis is not classified as an STI, healthcare professionals are responsible for educating patients about the significance of practicing safe sex, avoiding multiple sexual partners, and utilizing barrier protection methods. The enhancement of patient safety and improvement in patient outcomes can be achieved through interprofessional communication and collaboration.

A collaborative approach among healthcare professionals is paramount in optimizing patient-centered care and outcomes for bacterial vaginosis. Physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare providers must possess diverse skills, including clinical expertise in diagnosing and treating bacterial vaginosis and proficiency in patient communication and education. Strategy in bacterial vaginosis management involves evidence-based treatment protocols tailored to individual patient needs, with a focus on minimizing recurrence and addressing comorbidities. Ethics demand respect for patient autonomy, confidentiality, and informed consent throughout the care process. Responsibilities encompass timely and accurate diagnosis, appropriate medication management, and vigilant monitoring for complications. Interprofessional communication ensures seamless coordination of care, facilitating shared decision-making and holistic patient support. Ultimately, the collaborative efforts of healthcare professionals enhance patient safety, improve outcomes, and optimize team performance in addressing bacterial vaginosis and its associated challenges.