Introduction

The uterus is the Latin term for the womb, located between the female pelvis's bladder and rectum. It is a relatively superficial organ that can be imaged using a variety of modalities. Most commonly, ultrasound is the modality used for imaging the uterus. However, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) comes second to evaluate uterine pathology. Other rarer modalities include hysterosonogram, hysterosalpingogram, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT). Each of these modalities is useful in evaluating different aspects.

Modalities to Evaluate the Uterus

- Ultrasound

- CT/X-ray

- MRI

- PET-CT

- Hysterosonogram and hysterosalpingogram

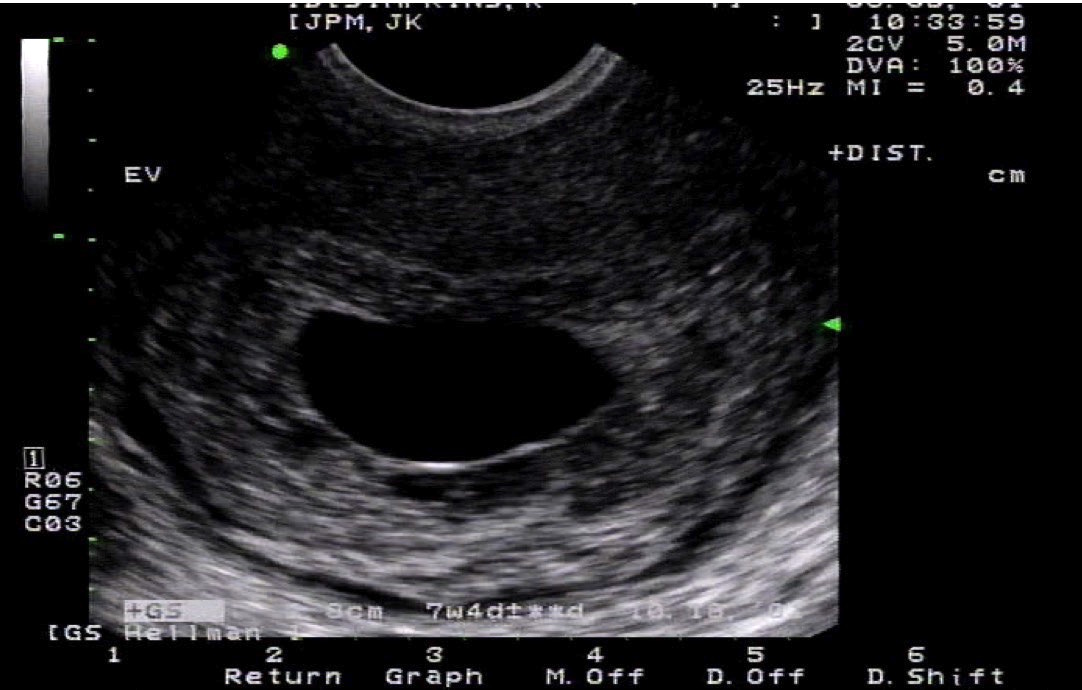

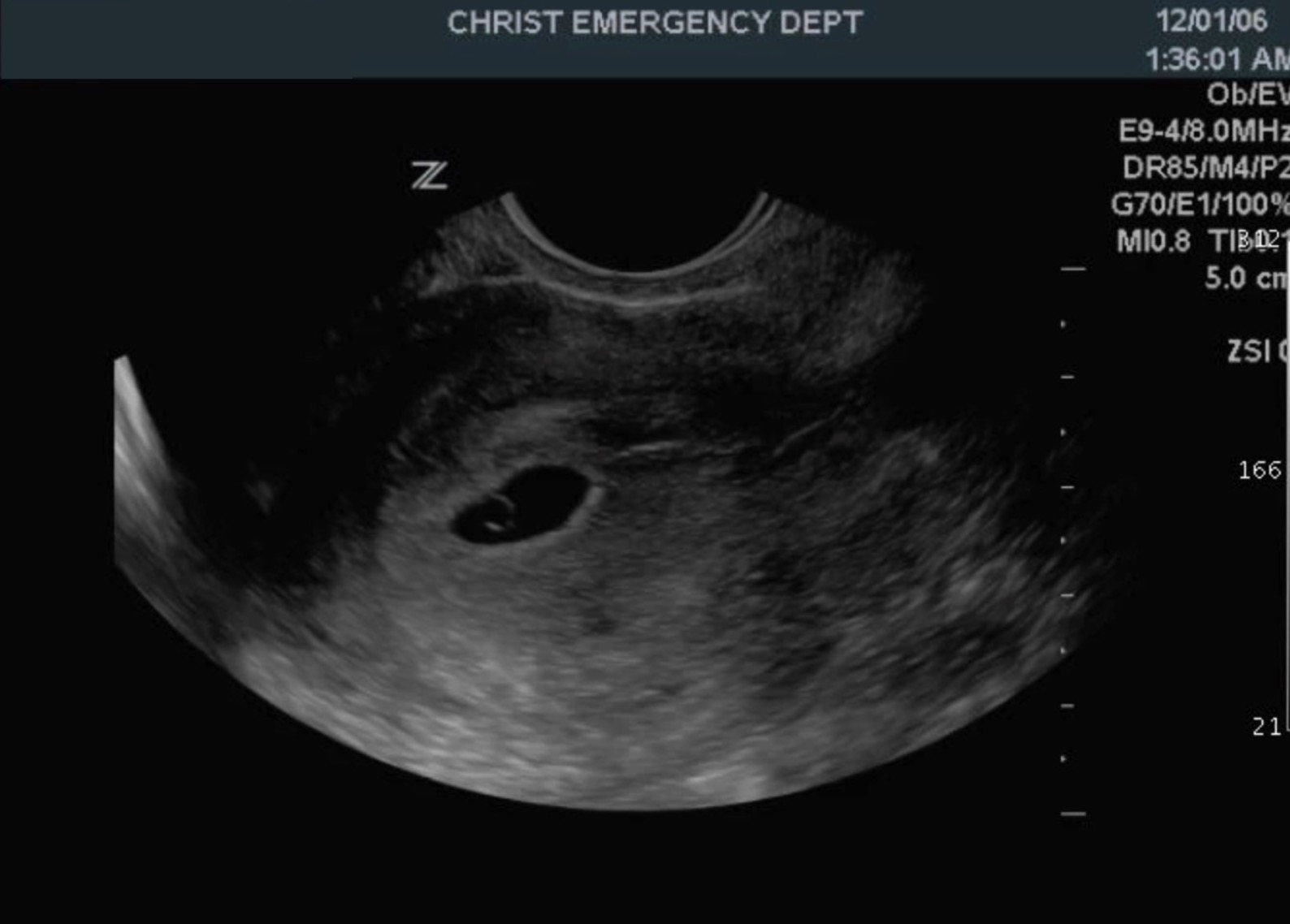

Imaging in Pregnancy

Pregnancy is a special physiological state and requires separate consideration. Imaging in pregnancy is usually by ultrasound (see Image. Uterus Ultrasound, Molar Pregnancy). Clinicians can assess the uterus, gestational product, and ovaries, which are assessable on ultrasound. The fetus can be monitored throughout pregnancy with transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound (see Images. Transabdominal Long Image of a Normal Uterus and Transvaginal Long Image of a Normal Uterus). The placenta and its variants can also be assessed on ultrasound. MRI imaging of the uterus during pregnancy may be necessary on rare occasions; this is usually to evaluate gestational trophoblastic disease or conditions such as endometriosis. The fetus can also undergo evaluation on MRI. Evaluation of gestational trophoblastic disease (GTN) presents a diagnostic dilemma as gadolinium contrast, useful in assessing GTN, is usually not administered during pregnancy. Gadolinium-based contrast agents can cross the placenta. Though the deleterious effects on the fetus remain unproven, it is considered to be a class C drug and is usually avoided in pregnant patients unless necessary. Hence, a noncontrast MRI is the norm for pregnant patients. CT and PET-CT for assessing uterus or gynecological malignancies are associated with ionizing radiation and are contraindicated in pregnant patients. However, depending on the clinical scenario and in special circumstances where a nonionizing modality is unavailable or not useful, CT may be performed, keeping the radiation levels as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA). PET-CT, in particular, uses 18-F-fluorodeoxyglucose, a radiopharmaceutical contraindicated in pregnant patients and crosses the placenta.[1] However, the study may be performed if the medical benefits outweigh the risks.

Anatomy

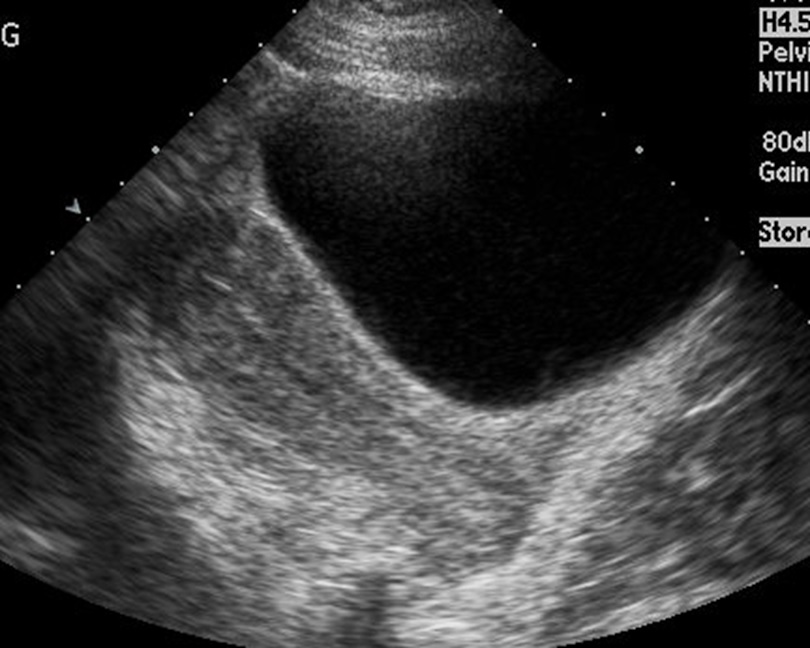

The normal adult uterus measures 6 to 9 cm in length.[2] It is usually anteverted but can be retroverted (see Image. A Retroverted Uterus With A Gestational Sac). Assessment of the uterus includes evaluation of the endometrial stripe, the junction zone, the myometrium, and the cervix. The endometrial stripe thickness varies from 1mm to 16mm in a menstruating female. The postmenopausal age group's thickness varies from 1 mm to 5 mm. However, in patients on hormonal therapy, up to 8 mm is acceptable in the absence of postmenopausal bleeding. The junctional zone varies up to 12 mm in thickness. The myometrium thickness varies widely depending on the physiological state of the woman. It also varies with the menstrual cycle. The cervix, endometrium, and myometrium are well visualized on ultrasound and MRI. However, the junctional zone is better assessed on MRI. The contour and anomalies of the uterus are also assessable on ultrasound and MRI.

Plain Films

An X-ray cannot evaluate the uterus. However, calcified fibroids may be visible on a pelvic X-ray.

Computed Tomography

Tissue differentiation is poor with CT, though the overall contour of the uterus and large exophytic masses are assessable. Larger endometrial lesions can be evaluated, especially if fluid is in the endometrial canal. However, beyond that, CT adds little value to uterine imaging.

Magnetic Resonance

MRI is the modality of choice given the high tissue spatial resolution and absence of ionizing radiation. The different layers of the uterus are distinctly visualized. The junctional zone can experience thickening in adenomyosis. The advantage of MRI is that it can also evaluate the adjacent structures, such as the ovaries, fallopian tubes, urinary bladder, and rectum. Deep pelvic lymph nodes, which are not well visualized on ultrasound, can also be assessed on MRI. Multiple sequences in different planes are obtained. Most common sequences include a sagittal T2-weighted image, coronal and axial T2, sagittal and or axial fat-saturated T2-weighted sequence, angled axials to evaluate the cervix and Mullerian duct anomalies, axial T1 weighted sequence including in and out of phase sequence, diffusion-weighted sequences, and dynamic sequences for evaluating the enhancement characteristics of the various uterine lesions.[3] Restricted diffusion sequences are invaluable in assessing mass lesions within and around the uterus.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasound is the most common and usually the first modality for evaluating the uterus. It can assess the anatomy and contour well. The probe can be placed transabdominally or transvaginally. Transvaginal images offer a better view of the endometrium and the entire myometrium. Color Doppler can evaluate vascularity within the lesions (see Image. Endovaginal Ultrasound of the Uterus).

Nuclear Medicine

PET-CT is useful in evaluating gynecological malignancies. Though MRI is superior and accurate for local extension and staging of the disease, distant metastasis in gynecological malignancies can be better assessed with PET-CT.[4]

Angiography

Hysterosalpingogram

Hysterosalpingogram (HSG) is performed by instilling an iodinated radiopaque, usually water-soluble, into the endometrial canal.[5] The cervix gets cannulated after sterile preparation, and a speculum is placed in the vagina. The dye is then instilled, and fluoroscopic images are obtained. The endometrial canal is evaluated for contour, filling defects, polyps, and fibroids. It is also used to assess the fallopian tubes during infertility workup. Patency of the fallopian tubes is confirmed when there is prompt spillage of contrast into the peritoneal cavity. The study is contraindicated in pregnancy and performed within the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. A negative pregnancy test is a must before the procedure. Hysterosonogram

This modality is similar to an HSG except that an ultrasound probe is introduced into the cervix after filling the uterine cavity with saline; this is helpful when an endometrial biopsy is negative. Images of the endometrial canal are obtained to evaluate for lesions such as polyp and fibroids. Submucosal fibroids can be differentiated from polyps as they are covered by a layer of endometrium, which can be visualized on ultrasound.[6] It is also helpful to evaluate focal versus diffuse endometrial pathology. Like HSG, a hysterosonogram is also performed in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. A negative pregnancy test is compulsory.

Clinical Significance

Uterine Anomalies The uterus develops from Mullerian ducts. The cervix and upper third of the vagina also develop from the Mullerian ducts.[7] The lower vagina derives from the ectoderm. As per the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, uterine anomalies can be classified into 6 types[8]:

- Type 1 (uterine hypoplasia or agenesis): Nondevelopment of the uterus/aplasia

- Type 2 (unicornuate uterus): A single, small uterine cavity that extends towards one side of the pelvis; this can have a rudimentary communicating or noncommunicating horn

- Type 3 (uterine idelphus): Two uterine cavities along with 2 cervices and longitudinal septa in the vaginal canal. No communication between the uterine cavities.

- Type 4 (bicornuate uterus): Complete or partial. Two symmetric horns. A complete bicornuate uterus has a septum extending from the fundus to the internal os. The fundal contour is concave, measuring greater than 1cm in depth. There is communication between the uterine cavities.

- Type 5 (septate uterus): Two uterine cavities but convex/flat contour of the fundus or shallow concavity less than 1 cm in depth.

- Type 6 (arcuate uterus): Usually a mild form of a bicornuate uterus. Mild superior indentation.

- Type 7 (diethylstilbestrol [DES] drug-related)

Imaging of Common Benign Conditions

The following conditions of the nonpregnant uterus can be evaluated using imaging:

Fibroids

Fibroids are almost ubiquitous. One-third of all hysterectomies in the United States of America result from fibroids. These are benign neoplasms due to the proliferation of smooth muscles and fibroblasts. Fibroids can be heterogeneous in appearance. Based on the location within the uterus, they can be:

- Submucosal

- Intramural

- Subserosal

- Parasitic (fibroids that lose connection with the uterine body)

On ultrasound, these are usually well-circumscribed lesions. Some of them can be calcified, which produces extensive shadowing. Assessment of fibroids on MRI is essential for preoperative planning, both for surgery and uterine artery embolization (UAE), a less invasive method for treating fibroids. The fibroids' size, volume, and location need to be noted. Fibroids are usually hypo or isointense on T2-weighted sequences. Fibroids that enhance on postcontrast images are nonnecrotic or viable fibroids and have a better prognosis following UAE. Necrotic or degenerated fibroids do not enhance. Subserosal fibroids are less likely to undergo necrosis and decrease in size following UAE than submucosal fibroids.[9][10] Postoperative assessment is frequently performed after UAE to assess the decline in the volume of the fibroids and to evaluate for complications. Adenomyosis

The presence of ectopic endometrial tissue within the myometrium is adenomyosis. Ultrasound and MRI are both useful for evaluating adenomyosis. On ultrasound, findings suggest adenomyosis includes heterogeneous myometrium—nonspecific but indicative of adenomyosis. This finding is termed pencil shadowing due to the proliferation of endometrial glands within the myometrium.MRI is a slightly more sensitive study for evaluating adenomyosis. Features on MRI suggestive of adenomyosis include:

- Thickening of the junctional zone beyond 12 mm

- The presence of tiny T2 bright foci within the myometrium indicates endometrial glands growing into the myometrium

- Focal adenomyosis, which presents as foci of ill-defined decreased T2 signal within the myometrium

These can be differentiated from fibroids due to their ill-defined margins compared to the well-defined borders of a fibroid. MRI is also helpful to evaluate the ovaries. Patients with adenomyosis frequently have endometriomas in the ovaries. The association of endometriomas and adenomyosis varies from 10% to 80%. Endometriomas are well-defined lesions in the ovaries with increased T1 signal and the presence of T2 shading. The presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus is called endometriosis. Deep endometriosis refers to the presence of endometrial tissue deep into the peritoneal surface. This condition can involve anywhere within the peritoneal cavity, including the cervix, vagina, serosal implants in the bowel wall, urinary bladder, and rectum. The signal intensity of endometriosis lesions can be variable. However, most lesions show the presence of T1 hyperintensity suggestive of hemorrhage.[2] Endometrial Polyps Hyperplasia and overgrowth of the endometrial stroma produce a polypoidal appearance with a vascular stalk. On ultrasound, these are seen as rounded, slightly hyperechoic lesions within the endometrial canal and can be sessile or pedunculated. A vascular stalk is usually present.[6] Ultrasound, hysterosonogram, and hysterosalpingogram are useful to evaluate polyps.

In conclusion, the uterus can be imaged using multiple modalities. However, ultrasound and MRI are the most commonly used modalities in uterine imaging.