Continuing Education Activity

Torticollis is a common diagnosis, and estimates are that 90 percent of individuals will exhibit at least one episode of torticollis throughout their lifetime. Typically, torticollis presents with abnormal rotation and flexion. However, there are several other positional presentations, which may include flexion, extension, and right or left tilt. Torticollis may be benign, as in cases of congenital torticollis, or malignant or due to serious causes such as brain injury. Most commonly, torticollis occurs due to dysfunctional local neuromuscular mechanisms, termed focal dystonia. Cervical dystonia is among the most common focal dystonias in adults. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of torticollis and highlights the role of interprofessional team members in collaborating to provide well-coordinated care and enhance outcomes for affected patients.

Objectives:

- Identify common presentations of torticollis.

- Explain the pathophysiology of torticollis.

- Review the management of torticollis.

- Outline the importance of improving coordination amongst the interprofessional team to enhance the delivery of care for patients affected by torticollis.

Introduction

Torticollis or twisted neck (tortum collum) of Italian origin "torti colli" is a vicious attitude of the head and neck, typically presenting with abnormal slope and rotation. There may be several presenting positions, including flexion, extension, right or left tilt. These have names such as horizontal torticollis, vertical, oblique, or torsion.

Torticollis is a common diagnosis, and estimates are that 90% of people will exhibit at least one episode of torticollis throughout their lives.

Torticollis may be benign (congenital torticollis) but may also be due to serious causes such as brain injury.

The most frequent and common cases seem to be related to dysfunctions in the local neuromuscular mechanisms (focal dystonia). Cervical dystonia is among the most common focal dystonias in adults, causing a tetanus contraction of the sternocleidomastoid and/or trapezius muscles.

Depending on the affected muscles, the shape of the neck will be different. It is worth noting that other changes in the position of the head and neck are not necessarily torticollis.[1][2]

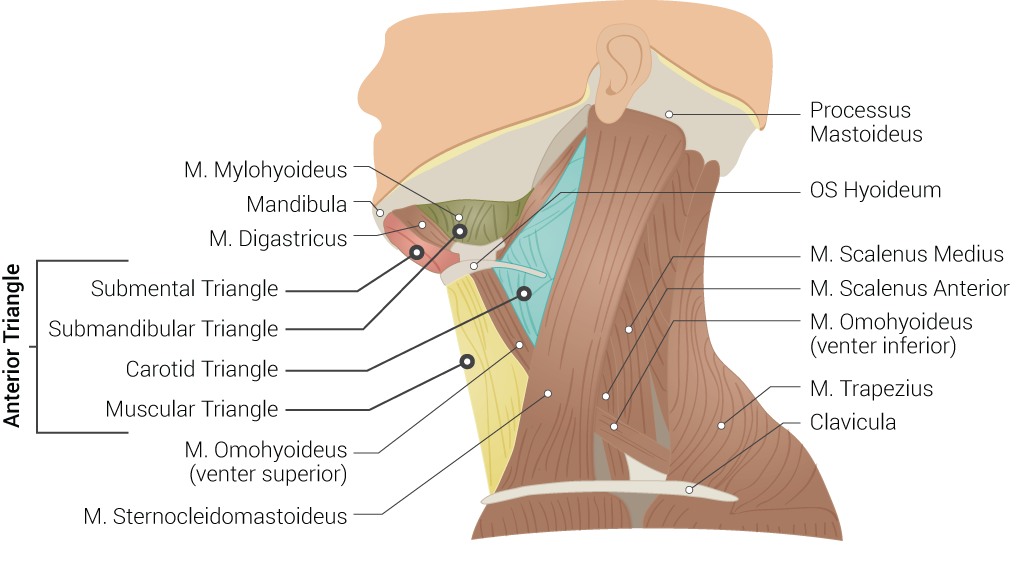

Cervical Muscular Anatomy:

The muscles of the neck form a complex system. Schematically, two levels are distinguished: superficial (long neck muscles) and deep (paravertebral muscles).

The primary muscles involved in cervical dystonia are:

The sternocleidomastoid is the most targeted muscle. It is in the anterior region of the neck, where it forms a visible and palpable mass. Its insertions on the sternum (sternum furcula), clavicle (medial aspect), occipital region (lateral neckline), and mastoid. The muscle fibers have an obliquely upward and outward direction. The action of the sternocleidomastoid is to perform contralateral rotation, ipsilateral inclination, and flexion of the head.

Other muscles of the region involved in torticollis include the splenius, the trapezius, the scapula, the scalenes, and the platysma.

There are eight sets of cervical nerves, outlined C1 to C8, and each pair leaves the spinal cord at the corresponding vertebral level. These nerves are particularly susceptible to nerve compression associated with pathological changes.[3][4][5]

Etiology

The etiologies of torticollis are diverse. It can be related to complex and/or serious diseases.

Torticollis classifies into several types:

- Congenital torticollis: During gestation or birth, trauma can occur that causes edema in the muscle, which can generate congenital fibrosis of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, causing a shortening of the fibers of this muscle.

- Dermatogenic pain: When there is an injury to the skin of the neck, and it shortens, this can lead to a limitation in movement, usually occurring in cases of burns or scars.

- Ocular torticollis: This refers to the paralysis of muscles involved with the inclination and rotation of the head (compensation) from the involvement of the oblique extraocular muscles.

- Rheumatological torticollis: This variant is secondary to various rheumatologic diseases.

- Torcicolo vestibular: Inner ear responsible for the balance, involving the labyrinth of the inner ear.

- Neurogenic tormentor: This results from any neurological disorder or accident, such as stroke or trauma.

- Spasmodic torticollis (dystonia): this is the most common cause of neck rigidity. This type results from increased muscle tone. The most common triggering factors include emotional stress, physical overload, or sudden movement.

Experimental models of torticollis show that torticollis can result from both local factors and central nervous system disorders.[6][7][8][9]

Cervical dystonia can subdivide into two groups:

Primary (or idiopathic) cervical dystonia and secondary cervical dystonia (or symptomatic). Primary dystonia, also called idiopathic dystonia, is characterized by the absence of lesions of the basal ganglia. Numerous studies have identified the genetic basis, revealing 25 genetic dystonias. Secondary cervical dystonia may follow trauma, drug use, or be the result of a pathological trigger. Its origin is, therefore, linked to a known external factor.[10][11]

Epidemiology

Torticollis is posttraumatic 10 to 20% of the time; the remainder is idiopathic. The onset of posttraumatic cervical dystonia is usually within days of injury and 3 to 12 months after injury in the delayed form.

Torticollis is usually a mixture of movements. Torticollis, with some element of rotation, is the most common type. After rotational torticollis, comes laterocollis, then retrocollis, with anterocollis being the rarest type.

There is a female to male predilection of 2 to 1. The onset of idiopathic cervical dystonia typically occurs in the 30 to 50 year age group. Congenital muscular torticollis is present in less than 0.4% of newborns.[12][13]

History and Physical

The clinicians should perform both a detailed history and a methodical, thorough clinical examination to diagnose torticollis and help to determine the management plan.[9]

In reviewing the history of present illness, identifying the characteristics of the torticollis is vital to determine an etiology. Important aspects include:

- Symptoms associated with torticollis (vomiting, fever or signs of infection, gait disturbances, balance problems, associated headaches, and vision changes)

- Emotional state

- Personal and family context when torticollis occurs in the neonatal period (birth details, the course of the neonatal period, known pathology such as chromosomal alterations, systemic disease, visceral or skeletal malformations, muscle fibrosis, strabismus

- Acute or chronic duration

- Underlying associated pathologic medical conditions

- Permanent versus transient or paroxysmal symptoms

- Recent changes in medication

- Age of onset of the initial episode

- The age of onset of torticollis makes it possible to immediately distinguish between congenital torticollis (present at birth or during the neonatal period) from acquired torticollis, which would present later in life

- Events leading up to the episode of torticollis (such as recent trauma

- Determining if the torticollis is painful or non-painful is crucial

- Pain present may be bony, central, muscular, or from previous radiation

The physical exam is also important in diagnosing torticollis. Areas of focus include[2][1][9]:

- The patient's posture

- Constant or intermittent head tilt

- Presence of any limitation of movement as well as any relieving factors

- Bony or muscular tenderness to palpation

The diagnosis of torticollis is straightforward in the typical form with lateral tilt and contralateral neck rotation, but if the patient presents in spine immobilization by EMS, a rigid form of the head, the inclination or rotation of the head may be isolated.[7][8][9]

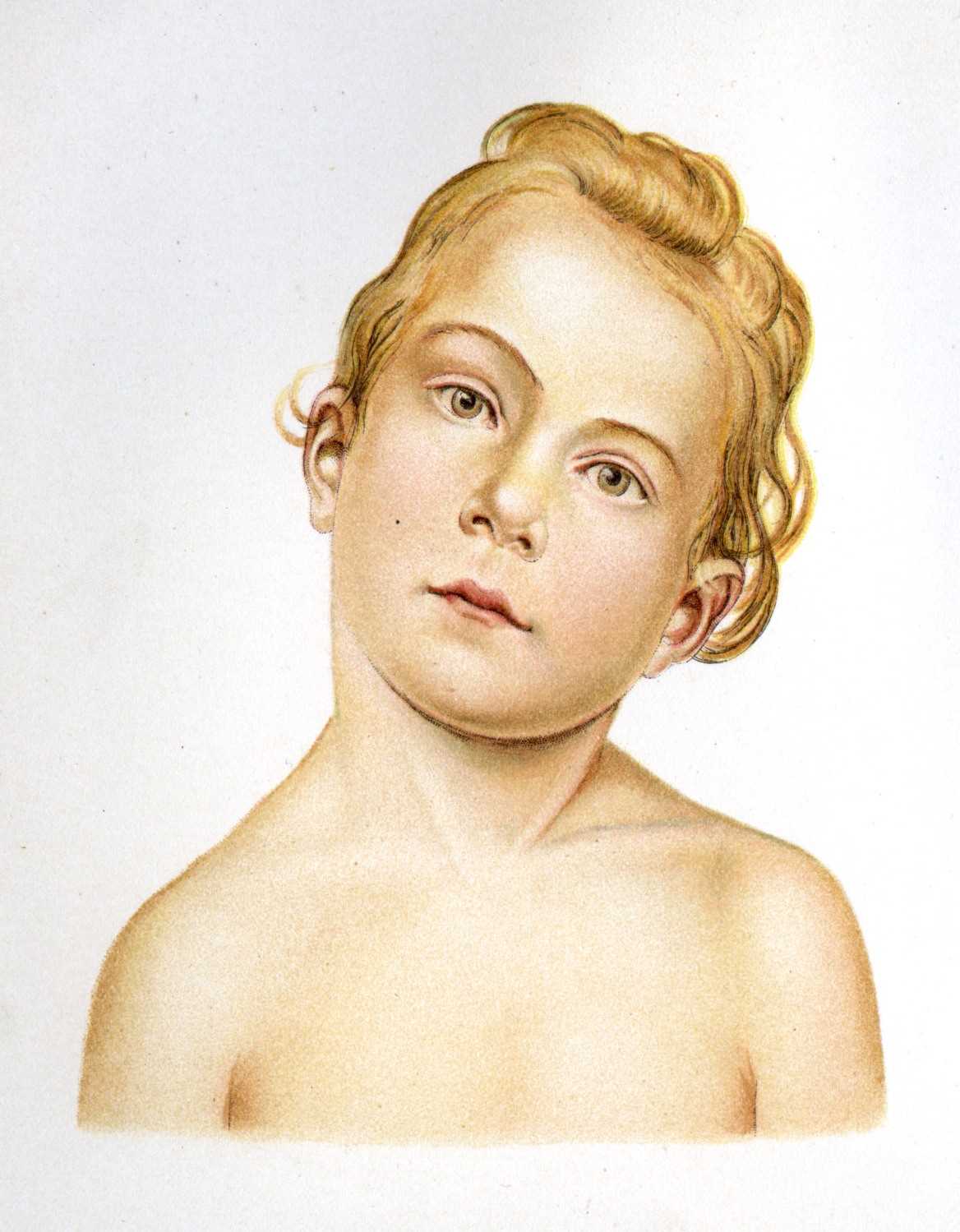

Moderate and severe forms of torticollis are typically evident from the physical examination. If left untreated in children, persistent torticollis is unsightly, uncomfortable, and potentially detrimental to the cervical spine and facial development.[2][14]

Evaluation

Clinical presentation and physical exam allow diagnosis in most cases of torticollis. Indications for imaging should be individualized, as deemed appropriate.

Diagnostic exams include radiography (X-ray), computed tomography (CT), ultrasound imaging, and laboratory analysis of blood (screening for metabolic or genetic factors).

In cases of spasmodic torticollis, the pain is unilateral and can radiate to the shoulder, and there is muscle stiffness. Proper observation of the cervical spine and scapular girdle should be done by assessing the active mobility of the spine and evaluating for pain in muscle movement. Passive mobility should undergo assessment sitting with and with caution due to the possibility of atlantoaxial subluxation. X-ray and CT imaging may be necessary to identify any anatomic abnormality (fracture, subluxation, etc.)

In persistent torticollis, it is essential to check for strabismus, nystagmus, signs of intracranial hypertension, or other focal neurological signs. Persistent torticollis in the presence of recurrent vomiting is a warning sign, and a thorough neurological examination is essential. In these cases, neuroimaging examinations are imperative to exclude intracranial injury. Ophthalmology consultation should be a consideration with abnormal extraocular movements of the eyes.

The presence of fever should lead to consideration of an infectious or inflammatory etiology. Excluding a septic otolaryngological focus or an osteoarticular infection is essential.

Examination to determine the presence of cervical adenopathy, an examination of the oropharynx, and otoscopy are important areas of focus on the physical examination. CT imaging should take place if there is suspicion of a retropharyngeal abscess. The presence of tenderness in the cervical spine may suggest osteomyelitis or spondylodiscitis. Laboratory testing has an auxiliary role in the diagnosis. MRI and scintigraphy are additional imaging studies that can aid in diagnosis.[2][9][11]

Treatment / Management

At present, there is no specific treatment to treat cervical dystonias. To minimize and relieve symptoms, pharmacological treatment options include benzodiazepines (treatment of anxiety and spasms), muscle relaxants (muscle relaxant), and anticholinergics (counteracting acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter in the nervous system). Another option is botulinum toxin injection.[15] Some etiologies of torticollis require corrective surgery. Physiotherapy and osteopathy are options for conservative treatment.[16][17] Physiotherapy plays an essential role in treating the vast majority of different forms and etiologies of torticollis.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

- Essential tremor

- Myasthenia gravis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Neuroleptic agent toxicity

- Parkinson disease

- Peritonsillar abscess

- Rehabilitation and cerebral palsy

- Retropharyngeal abscess

- Spinal hematoma

- Tardive dyskinesia

- Wilson disease

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As there are many different etiologies of torticollis, depending on the etiology of the condition, it may be necessary to obtain specialty consultation (physiotherapy, orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, neurology, neurosurgery, otorhinolaryngology) for the treatment of these patients.

The outcomes depend on the cause. Recurrences are common with all treatments. Chronic torticollis leads to poor aesthetics and isolation. Thus, some of these patients may benefit from a mental health nurse consult.

In cases of torticollis, an interprofessional team approach to include physicians, mid-level practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, and even chiropractors working collaboratively can achieve the best outcomes for the patient. [Level V]