[1]

Park JS, Kim J, Elghiaty A, Ham WS. Recent global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Medicine. 2018 Sep:97(37):e12390. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012390. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30213007]

[2]

Boccellino M, Vanacore D, Zappavigna S, Cavaliere C, Rossetti S, D'Aniello C, Chieffi P, Amler E, Buonerba C, Di Lorenzo G, Di Franco R, Izzo A, Piscitelli R, Iovane G, Muto P, Botti G, Perdonà S, Caraglia M, Facchini G. Testicular cancer from diagnosis to epigenetic factors. Oncotarget. 2017 Nov 28:8(61):104654-104663. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20992. Epub 2017 Sep 18

[PubMed PMID: 29262668]

[3]

Smith ZL, Werntz RP, Eggener SE. Testicular Cancer: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management. The Medical clinics of North America. 2018 Mar:102(2):251-264. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.10.003. Epub 2017 Dec 21

[PubMed PMID: 29406056]

[4]

Baird DC,Meyers GJ,Hu JS, Testicular Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment. American family physician. 2018 Feb 15;

[PubMed PMID: 29671528]

[5]

Jørgensen N, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Main KM, Skakkebaek NE. Testicular dysgenesis syndrome comprises some but not all cases of hypospadias and impaired spermatogenesis. International journal of andrology. 2010 Apr:33(2):298-303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2009.01050.x. Epub 2010 Feb 4

[PubMed PMID: 20132348]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[6]

Grasso C, Zugna D, Fiano V, Robles Rodriguez N, Maule M, Gillio-Tos A, Ciuffreda L, Lista P, Segnan N, Merletti F, Richiardi L. Subfertility and Risk of Testicular Cancer in the EPSAM Case-Control Study. PloS one. 2016:11(12):e0169174. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169174. Epub 2016 Dec 30

[PubMed PMID: 28036409]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[7]

Hughes IA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, Lee PA, Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society/European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology Consensus Group. Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Journal of pediatric urology. 2006 Jun:2(3):148-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.03.004. Epub 2006 May 23

[PubMed PMID: 18947601]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

Peng X,Zeng X,Peng S,Deng D,Zhang J, The association risk of male subfertility and testicular cancer: a systematic review. PloS one. 2009

[PubMed PMID: 19440348]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

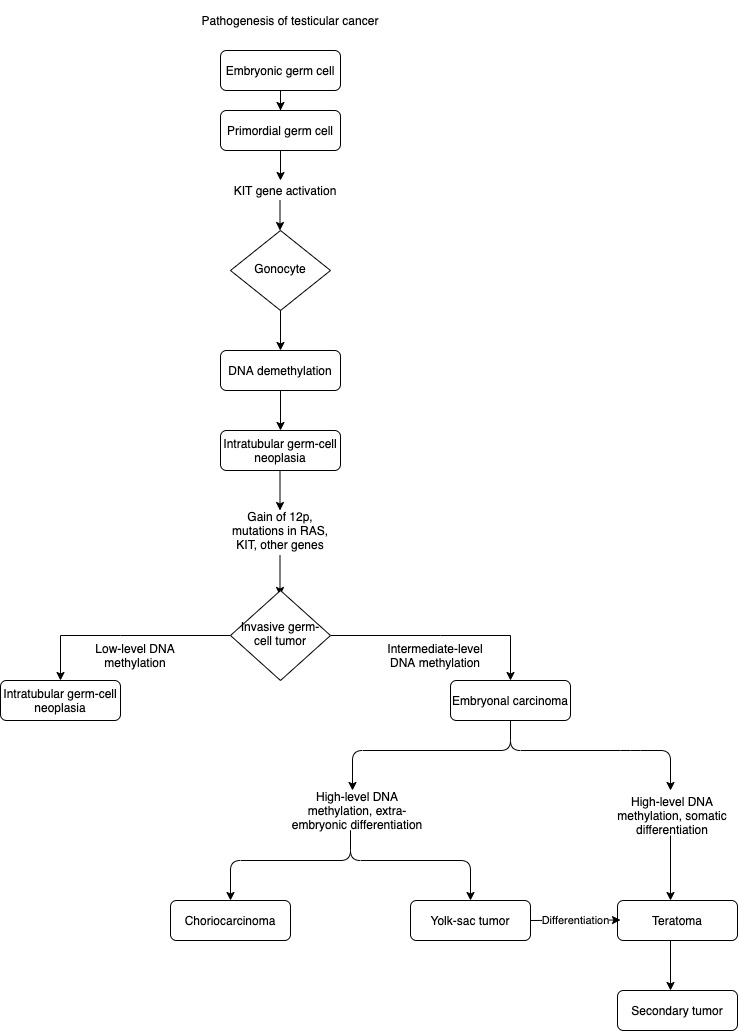

[9]

Kharazmi E, Hemminki K, Pukkala E, Sundquist K, Tryggvadottir L, Tretli S, Olsen JH, Fallah M. Cancer Risk in Relatives of Testicular Cancer Patients by Histology Type and Age at Diagnosis: A Joint Study from Five Nordic Countries. European urology. 2015 Aug:68(2):283-9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.031. Epub 2015 Apr 23

[PubMed PMID: 25913387]

[10]

Ferguson L, Agoulnik AI. Testicular cancer and cryptorchidism. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2013:4():32. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00032. Epub 2013 Mar 20

[PubMed PMID: 23519268]

[12]

Del Risco Kollerud R,Ruud E,Haugnes HS,Cannon-Albright LA,Thoresen M,Nafstad P,Vlatkovic L,Blaasaas KG,Næss Ø,Claussen B, Family history of cancer and risk of paediatric and young adult's testicular cancer: A Norwegian cohort study. British journal of cancer. 2019 May

[PubMed PMID: 30967648]

[13]

Hemminki K, Chen B. Familial risks in testicular cancer as aetiological clues. International journal of andrology. 2006 Feb:29(1):205-10

[PubMed PMID: 16466541]

[14]

Garolla A, Vitagliano A, Muscianisi F, Valente U, Ghezzi M, Andrisani A, Ambrosini G, Foresta C. Role of Viral Infections in Testicular Cancer Etiology: Evidence From a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2019:10():355. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00355. Epub 2019 Jun 12

[PubMed PMID: 31263452]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[15]

Coupland CA, Chilvers CE, Davey G, Pike MC, Oliver RT, Forman D. Risk factors for testicular germ cell tumours by histological tumour type. United Kingdom Testicular Cancer Study Group. British journal of cancer. 1999 Aug:80(11):1859-63

[PubMed PMID: 10468310]

[16]

Haughey BP, Graham S, Brasure J, Zielezny M, Sufrin G, Burnett WS. The epidemiology of testicular cancer in upstate New York. American journal of epidemiology. 1989 Jul:130(1):25-36

[PubMed PMID: 2568087]

[17]

Depue RH, Pike MC, Henderson BE. Estrogen exposure during gestation and risk of testicular cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1983 Dec:71(6):1151-5

[PubMed PMID: 6140323]

[18]

Kuczyk MA, Serth J, Bokemeyer C, Jonassen J, Machtens S, Werner M, Jonas U. Alterations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in carcinoma in situ of the testis. Cancer. 1996 Nov 1:78(9):1958-66

[PubMed PMID: 8909317]

[19]

Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ. Testicular germ-cell cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 1997 Jul 24:337(4):242-53

[PubMed PMID: 9227931]

[20]

Andreassen KE, Kristiansen W, Karlsson R, Aschim EL, Dahl O, Fosså SD, Adami HO, Wiklund F, Haugen TB, Grotmol T. Genetic variation in AKT1, PTEN and the 8q24 locus, and the risk of testicular germ cell tumor. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2013 Jul:28(7):1995-2002. doi: 10.1093/humrep/det127. Epub 2013 May 2

[PubMed PMID: 23639623]

[21]

Loveday C, Litchfield K, Levy M, Holroyd A, Broderick P, Kote-Jarai Z, Dunning AM, Muir K, Peto J, Eeles R, Easton DF, Dudakia D, Orr N, Pashayan N, Reid A, Huddart RA, Houlston RS, Turnbull C. Validation of loci at 2q14.2 and 15q21.3 as risk factors for testicular cancer. Oncotarget. 2018 Feb 27:9(16):12630-12638. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23117. Epub 2017 Dec 7

[PubMed PMID: 29560096]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[22]

Litchfield K, Loveday C, Levy M, Dudakia D, Rapley E, Nsengimana J, Bishop DT, Reid A, Huddart R, Broderick P, Houlston RS, Turnbull C. Large-scale Sequencing of Testicular Germ Cell Tumour (TGCT) Cases Excludes Major TGCT Predisposition Gene. European urology. 2018 Jun:73(6):828-831. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.01.021. Epub 2018 Feb 9

[PubMed PMID: 29433971]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[23]

Looijenga LH, Gillis AJ, Stoop H, Hersmus R, Oosterhuis JW. Relevance of microRNAs in normal and malignant development, including human testicular germ cell tumours. International journal of andrology. 2007 Aug:30(4):304-14; discussion 314-5

[PubMed PMID: 17573854]

[25]

Ehrlich Y, Margel D, Lubin MA, Baniel J. Advances in the treatment of testicular cancer. Translational andrology and urology. 2015 Jun:4(3):381-90. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.06.02. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26816836]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[26]

Fosså SD, Chen J, Schonfeld SJ, McGlynn KA, McMaster ML, Gail MH, Travis LB. Risk of contralateral testicular cancer: a population-based study of 29,515 U.S. men. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005 Jul 20:97(14):1056-66

[PubMed PMID: 16030303]

[27]

Chieffi P, Chieffi S. Molecular biomarkers as potential targets for therapeutic strategies in human testicular germ cell tumors: an overview. Journal of cellular physiology. 2013 Aug:228(8):1641-6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24328. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23359388]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

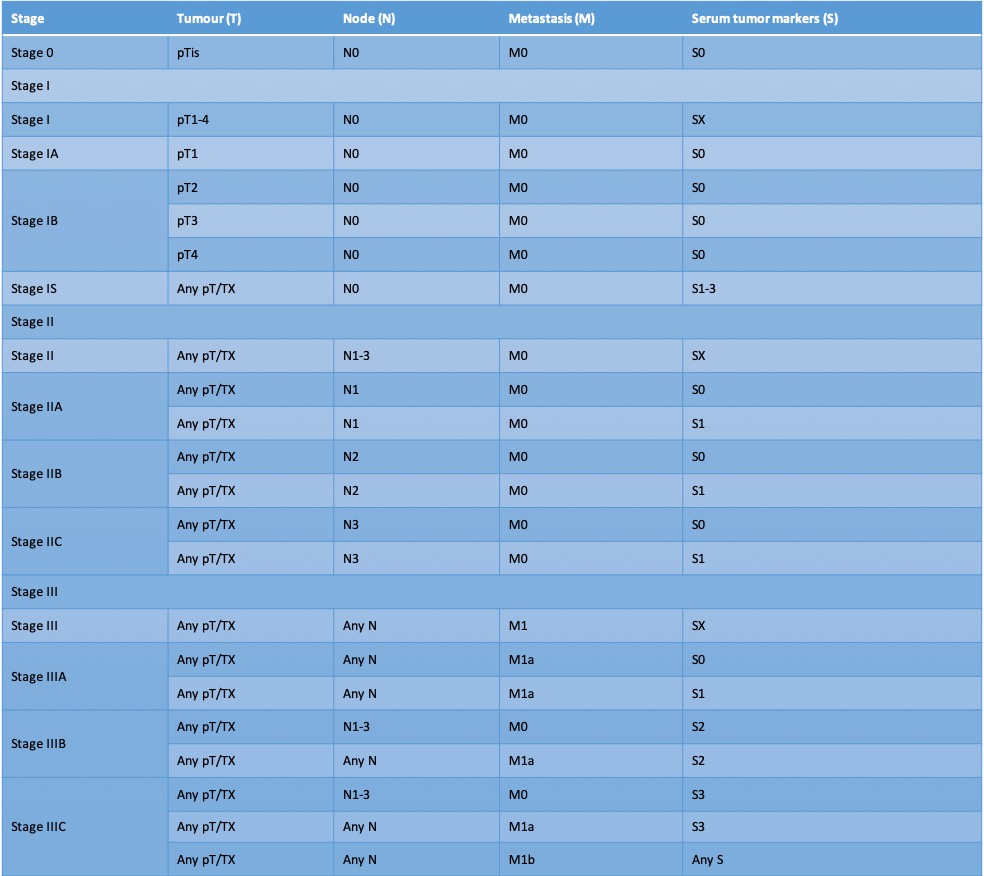

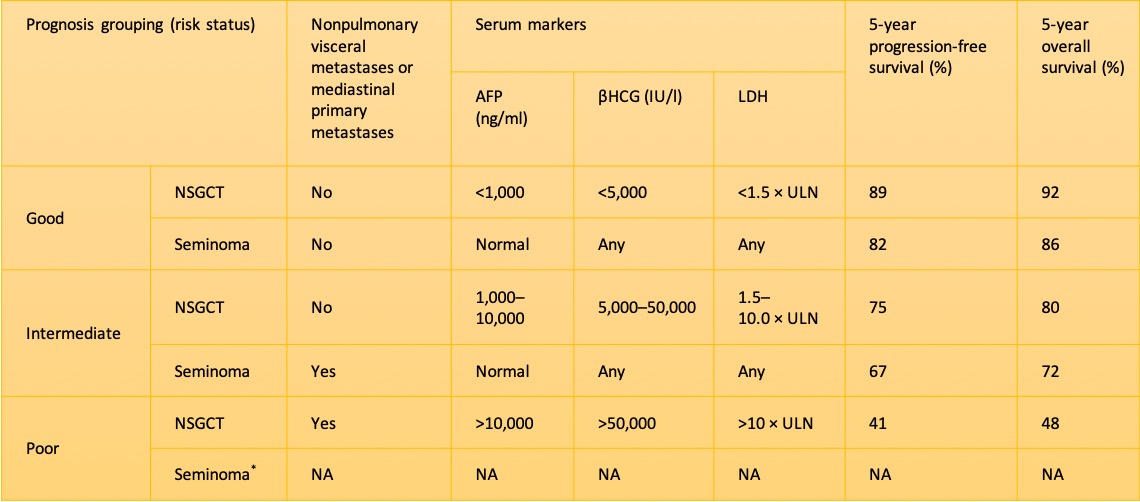

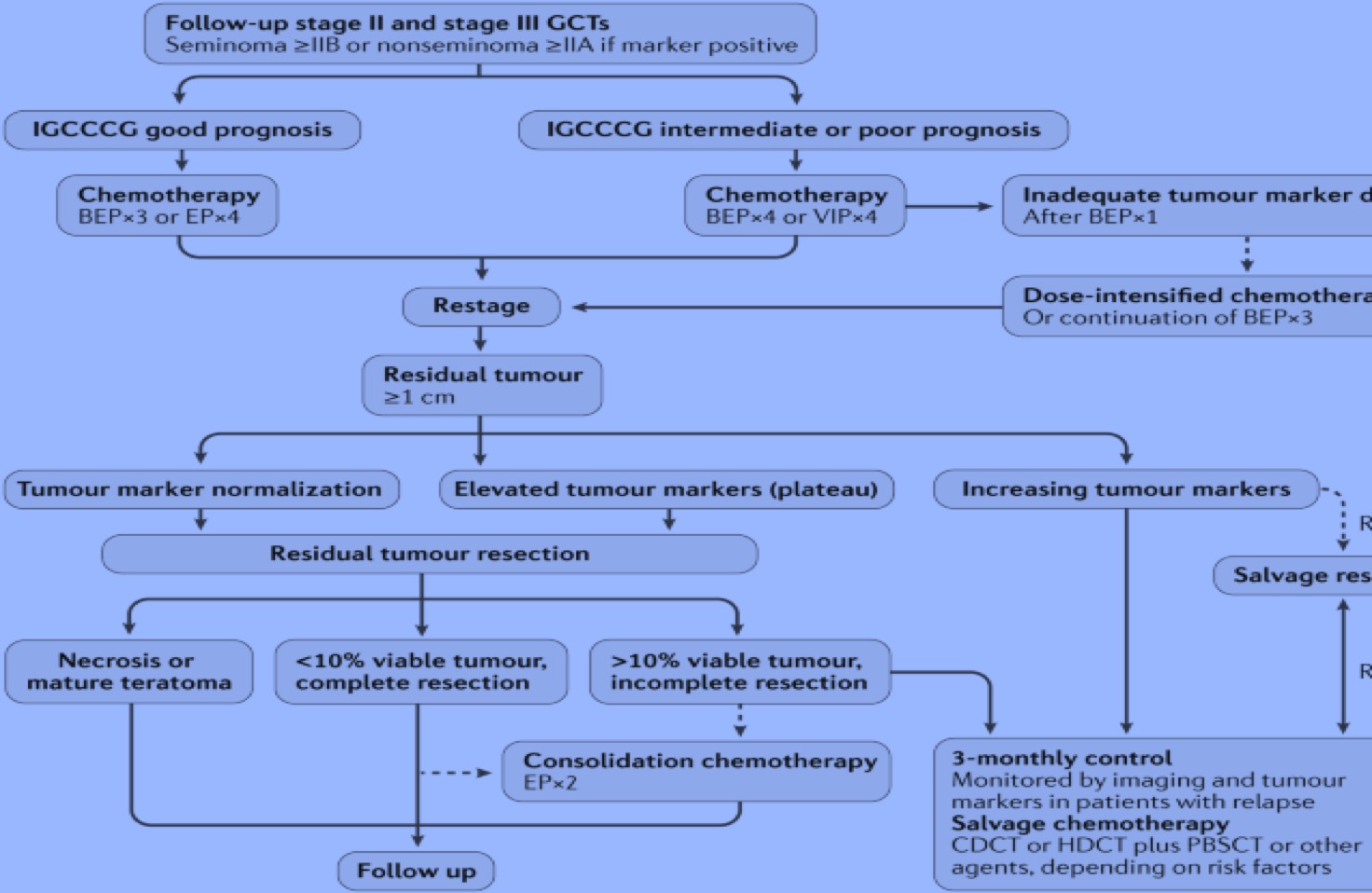

[28]

Rajpert-De Meyts E, Developmental model for the pathogenesis of testicular carcinoma in situ: genetic and environmental aspects. Human reproduction update. 2006 May-Jun;

[PubMed PMID: 16540528]

[29]

Sperger JM, Chen X, Draper JS, Antosiewicz JE, Chon CH, Jones SB, Brooks JD, Andrews PW, Brown PO, Thomson JA. Gene expression patterns in human embryonic stem cells and human pluripotent germ cell tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003 Nov 11:100(23):13350-5

[PubMed PMID: 14595015]

[30]

Almstrup K, Hoei-Hansen CE, Nielsen JE, Wirkner U, Ansorge W, Skakkebaek NE, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Leffers H. Genome-wide gene expression profiling of testicular carcinoma in situ progression into overt tumours. British journal of cancer. 2005 May 23:92(10):1934-41

[PubMed PMID: 15856041]

[31]

Kanetsky PA, Mitra N, Vardhanabhuti S, Li M, Vaughn DJ, Letrero R, Ciosek SL, Doody DR, Smith LM, Weaver J, Albano A, Chen C, Starr JR, Rader DJ, Godwin AK, Reilly MP, Hakonarson H, Schwartz SM, Nathanson KL. Common variation in KITLG and at 5q31.3 predisposes to testicular germ cell cancer. Nature genetics. 2009 Jul:41(7):811-5. doi: 10.1038/ng.393. Epub 2009 May 31

[PubMed PMID: 19483682]

[32]

Turnbull C, Rapley EA, Seal S, Pernet D, Renwick A, Hughes D, Ricketts M, Linger R, Nsengimana J, Deloukas P, Huddart RA, Bishop DT, Easton DF, Stratton MR, Rahman N, UK Testicular Cancer Collaboration. Variants near DMRT1, TERT and ATF7IP are associated with testicular germ cell cancer. Nature genetics. 2010 Jul:42(7):604-7. doi: 10.1038/ng.607. Epub 2010 Jun 13

[PubMed PMID: 20543847]

[33]

Rapley EA,Turnbull C,Al Olama AA,Dermitzakis ET,Linger R,Huddart RA,Renwick A,Hughes D,Hines S,Seal S,Morrison J,Nsengimana J,Deloukas P,Rahman N,Bishop DT,Easton DF,Stratton MR, A genome-wide association study of testicular germ cell tumor. Nature genetics. 2009 Jul;

[PubMed PMID: 19483681]

[34]

Sheikine Y, Genega E, Melamed J, Lee P, Reuter VE, Ye H. Molecular genetics of testicular germ cell tumors. American journal of cancer research. 2012:2(2):153-67

[PubMed PMID: 22432056]

[35]

Elzinga-Tinke JE, Dohle GR, Looijenga LH. Etiology and early pathogenesis of malignant testicular germ cell tumors: towards possibilities for preinvasive diagnosis. Asian journal of andrology. 2015 May-Jun:17(3):381-93. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.148079. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25791729]

[36]

Koul S, Houldsworth J, Mansukhani MM, Donadio A, McKiernan JM, Reuter VE, Bosl GJ, Chaganti RS, Murty VV. Characteristic promoter hypermethylation signatures in male germ cell tumors. Molecular cancer. 2002 Nov 28:1():8

[PubMed PMID: 12495446]

[37]

Williamson SR,Delahunt B,Magi-Galluzzi C,Algaba F,Egevad L,Ulbright TM,Tickoo SK,Srigley JR,Epstein JI,Berney DM, The World Health Organization 2016 classification of testicular germ cell tumours: a review and update from the International Society of Urological Pathology Testis Consultation Panel. Histopathology. 2017 Feb;

[PubMed PMID: 27747907]

[38]

Bosl GJ, Vogelzang NJ, Goldman A, Fraley EE, Lange PH, Levitt SH, Kennedy BJ. Impact of delay in diagnosis on clinical stage of testicular cancer. Lancet (London, England). 1981 Oct 31:2(8253):970-3

[PubMed PMID: 6117736]

[39]

Stephenson A, Eggener SE, Bass EB, Chelnick DM, Daneshmand S, Feldman D, Gilligan T, Karam JA, Leibovich B, Liauw SL, Masterson TA, Meeks JJ, Pierorazio PM, Sharma R, Sheinfeld J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Stage Testicular Cancer: AUA Guideline. The Journal of urology. 2019 Aug:202(2):272-281. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000000318. Epub 2019 Jul 8

[PubMed PMID: 31059667]

[40]

Gilligan T, Lin DW, Aggarwal R, Chism D, Cost N, Derweesh IH, Emamekhoo H, Feldman DR, Geynisman DM, Hancock SL, LaGrange C, Levine EG, Longo T, Lowrance W, McGregor B, Monk P, Picus J, Pierorazio P, Rais-Bahrami S, Saylor P, Sircar K, Smith DC, Tzou K, Vaena D, Vaughn D, Yamoah K, Yamzon J, Johnson-Chilla A, Keller J, Pluchino LA. Testicular Cancer, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2019 Dec:17(12):1529-1554. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0058. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31805523]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[41]

Wood L, Kollmannsberger C, Jewett M, Chung P, Hotte S, O'Malley M, Sweet J, Anson-Cartwright L, Winquist E, North S, Tyldesley S, Sturgeon J, Gospodarowicz M, Segal R, Cheng T, Venner P, Moore M, Albers P, Huddart R, Nichols C, Warde P. Canadian consensus guidelines for the management of testicular germ cell cancer. Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l'Association des urologues du Canada. 2010 Apr:4(2):e19-38

[PubMed PMID: 20368885]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[42]

Kreydin EI, Barrisford GW, Feldman AS, Preston MA. Testicular cancer: what the radiologist needs to know. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2013 Jun:200(6):1215-25. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.10319. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23701056]

[43]

Necas M,Muthupalaniappaan M,Barnard C, Ultrasound morphological patterns of testicular tumours, correlation with histopathology. Journal of medical radiation sciences. 2020 Sep 1

[PubMed PMID: 32869524]

[44]

Capelouto CC, Clark PE, Ransil BJ, Loughlin KR. A review of scrotal violation in testicular cancer: is adjuvant local therapy necessary? The Journal of urology. 1995 Mar:153(3 Pt 2):981-5

[PubMed PMID: 7853587]

[45]

Donohue JP. Evolution of retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy (RPLND) in the management of non-seminomatous testicular cancer (NSGCT). Urologic oncology. 2003 Mar-Apr:21(2):129-32

[PubMed PMID: 12856641]

[46]

Sheinfeld J. Mapping studies and modified templates in nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Nature clinical practice. Urology. 2007 Feb:4(2):60-1

[PubMed PMID: 17287863]

[47]

Donohue JP, Zachary JM, Maynard BR. Distribution of nodal metastases in nonseminomatous testis cancer. The Journal of urology. 1982 Aug:128(2):315-20

[PubMed PMID: 7109099]

[48]

von Eyben FE, Laboratory markers and germ cell tumors. Critical reviews in clinical laboratory sciences. 2003 Aug

[PubMed PMID: 14582602]

[49]

Milose JC, Filson CP, Weizer AZ, Hafez KS, Montgomery JS. Role of biochemical markers in testicular cancer: diagnosis, staging, and surveillance. Open access journal of urology. 2011 Dec 30:4():1-8. doi: 10.2147/OAJU.S15063. Epub 2011 Dec 30

[PubMed PMID: 24198649]

[50]

Hotakainen K, Ljungberg B, Paju A, Rasmuson T, Alfthan H, Stenman UH. The free beta-subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin as a prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. British journal of cancer. 2002 Jan 21:86(2):185-9

[PubMed PMID: 11870503]

[51]

Stenman UH, Alfthan H, Hotakainen K. Human chorionic gonadotropin in cancer. Clinical biochemistry. 2004 Jul:37(7):549-61

[PubMed PMID: 15234236]

[52]

Staples J. Alphafetoprotein, cancer, and benign conditions. Lancet (London, England). 1986 Nov 29:2(8518):1277

[PubMed PMID: 2431238]

[53]

Deshpande N, Chavan R, Bale G, Avanthi US, Aslam M, Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Ravikanth VV. Hereditary Persistence of Alpha-Fetoprotein Is Associated with the -119G}A Polymorphism in AFP Gene. ACG case reports journal. 2017:4():e33. doi: 10.14309/crj.2017.33. Epub 2017 Mar 1

[PubMed PMID: 28286798]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[54]

Badia RR,Abe D,Wong D,Singla N,Savelyeva A,Chertack N,Woldu SL,Lotan Y,Mauck R,Ouyang D,Meng X,Lewis CM,Majmudar K,Jia L,Kapur P,Xu L,Frazier AL,Margulis V,Strand DW,Coleman N,Murray MJ,Amatruda JF,Lafin JT,Bagrodia A, Real-World Application of Pre-orchiectomy miR-371a-3p Test in Testicular Germ Cell Tumor Management. The Journal of urology. 2020 Aug 28

[PubMed PMID: 32856980]

[55]

Spiekermann M, Belge G, Winter N, Ikogho R, Balks T, Bullerdiek J, Dieckmann KP. MicroRNA miR-371a-3p in serum of patients with germ cell tumours: evaluations for establishing a serum biomarker. Andrology. 2015 Jan:3(1):78-84. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2014.00269.x. Epub 2014 Sep 4

[PubMed PMID: 25187505]

[56]

Esposito F, Boscia F, Franco R, Tornincasa M, Fusco A, Kitazawa S, Looijenga LH, Chieffi P. Down-regulation of oestrogen receptor-β associates with transcriptional co-regulator PATZ1 delocalization in human testicular seminomas. The Journal of pathology. 2011 May:224(1):110-20. doi: 10.1002/path.2846. Epub 2011 Mar 7

[PubMed PMID: 21381029]

[57]

Chieffi P. Aurora B: A new promising therapeutic target in cancer. Intractable & rare diseases research. 2018 May:7(2):141-144. doi: 10.5582/irdr.2018.01018. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29862159]

[58]

Portella G,Passaro C,Chieffi P, Aurora B: a new prognostic marker and therapeutic target in cancer. Current medicinal chemistry. 2011

[PubMed PMID: 21143115]

[59]

Hart AH, Hartley L, Parker K, Ibrahim M, Looijenga LH, Pauchnik M, Chow CW, Robb L. The pluripotency homeobox gene NANOG is expressed in human germ cell tumors. Cancer. 2005 Nov 15:104(10):2092-8

[PubMed PMID: 16206293]

[60]

De Martino M, Esposito F, Pellecchia S, Cortez Cardoso Penha R, Botti G, Fusco A, Chieffi P. HMGA1-Regulating microRNAs Let-7a and miR-26a are Downregulated in Human Seminomas. International journal of molecular sciences. 2020 Apr 24:21(8):. doi: 10.3390/ijms21083014. Epub 2020 Apr 24

[PubMed PMID: 32344629]

[61]

Franco R, Esposito F, Fedele M, Liguori G, Pierantoni GM, Botti G, Tramontano D, Fusco A, Chieffi P. Detection of high-mobility group proteins A1 and A2 represents a valid diagnostic marker in post-pubertal testicular germ cell tumours. The Journal of pathology. 2008 Jan:214(1):58-64

[PubMed PMID: 17935122]

[62]

Feldman DR,Bosl GJ,Sheinfeld J,Motzer RJ, Medical treatment of advanced testicular cancer. JAMA. 2008 Feb 13;

[PubMed PMID: 18270356]

[63]

Paffenholz P,Pfister D,Heidenreich A, Testis-preserving strategies in testicular germ cell tumors and germ cell neoplasia {i}in situ{/i}. Translational andrology and urology. 2020 Jan

[PubMed PMID: 32055482]

[64]

Mortensen MS, Lauritsen J, Gundgaard MG, Agerbæk M, Holm NV, Christensen IJ, von der Maase H, Daugaard G. A nationwide cohort study of stage I seminoma patients followed on a surveillance program. European urology. 2014 Dec:66(6):1172-8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.07.001. Epub 2014 Jul 23

[PubMed PMID: 25064686]

[65]

Aparicio J, Maroto P, García Del Muro X, Sánchez-Muñoz A, Gumà J, Margelí M, Sáenz A, Sagastibelza N, Castellano D, Arranz JA, Hervás D, Bastús R, Fernández-Aramburo A, Sastre J, Terrasa J, López-Brea M, Dorca J, Almenar D, Carles J, Hernández A, Germà JR. Prognostic factors for relapse in stage I seminoma: a new nomogram derived from three consecutive, risk-adapted studies from the Spanish Germ Cell Cancer Group (SGCCG). Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2014 Nov:25(11):2173-2178. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu437. Epub 2014 Sep 10

[PubMed PMID: 25210015]

[66]

Tandstad T, Smaaland R, Solberg A, Bremnes RM, Langberg CW, Laurell A, Stierner UK, Ståhl O, Cavallin-Ståhl EK, Klepp OH, Dahl O, Cohn-Cedermark G. Management of seminomatous testicular cancer: a binational prospective population-based study from the Swedish norwegian testicular cancer study group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Feb 20:29(6):719-25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1044. Epub 2011 Jan 4

[PubMed PMID: 21205748]

[67]

Beard CJ,Travis LB,Chen MH,Arvold ND,Nguyen PL,Martin NE,Kuban DA,Ng AK,Hoffman KE, Outcomes in stage I testicular seminoma: a population-based study of 9193 patients. Cancer. 2013 Aug 1

[PubMed PMID: 23633409]

[68]

Chung P, Parker C, Panzarella T, Gospodarowicz MK, Jewett S, Milosevic MF, Catton CN, Bayley AJ, Tew-George B, Moore M, Sturgeon JF, Warde P. Surveillance in stage I testicular seminoma - risk of late relapse. The Canadian journal of urology. 2002 Oct:9(5):1637-40

[PubMed PMID: 12431325]

[69]

Tabakin AL, Shinder BM, Kim S, Rivera-Nunez Z, Polotti CF, Modi PK, Sterling JA, Farber NJ, Radadia KD, Parikh RR, Kim IY, Saraiya B, Mayer TM, Singer EA, Jang TL. Retroperitoneal Lymph Node Dissection as Primary Treatment for Men With Testicular Seminoma: Utilization and Survival Analysis Using the National Cancer Data Base, 2004-2014. Clinical genitourinary cancer. 2020 Apr:18(2):e194-e201. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2019.10.018. Epub 2019 Nov 6

[PubMed PMID: 31818649]

[70]

Daugaard G, Gundgaard MG, Mortensen MS, Agerbæk M, Holm NV, Rørth M, von der Maase H, Christensen IJ, Lauritsen J. Surveillance for stage I nonseminoma testicular cancer: outcomes and long-term follow-up in a population-based cohort. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014 Dec 1:32(34):3817-23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5831. Epub 2014 Sep 29

[PubMed PMID: 25267754]

[71]

Kollmannsberger C,Tandstad T,Bedard PL,Cohn-Cedermark G,Chung PW,Jewett MA,Powles T,Warde PR,Daneshmand S,Protheroe A,Tyldesley S,Black PC,Chi K,So AI,Moore MJ,Nichols CR, Patterns of relapse in patients with clinical stage I testicular cancer managed with active surveillance. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Jan 1

[PubMed PMID: 25135991]

[72]

Albers P, Siener R, Krege S, Schmelz HU, Dieckmann KP, Heidenreich A, Kwasny P, Pechoel M, Lehmann J, Kliesch S, Köhrmann KU, Fimmers R, Weissbach L, Loy V, Wittekind C, Hartmann M, German Testicular Cancer Study Group. Randomized phase III trial comparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection with one course of bleomycin and etoposide plus cisplatin chemotherapy in the adjuvant treatment of clinical stage I Nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors: AUO trial AH 01/94 by the German Testicular Cancer Study Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 Jun 20:26(18):2966-72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.0899. Epub 2008 May 5

[PubMed PMID: 18458040]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[73]

Tandstad T, Dahl O, Cohn-Cedermark G, Cavallin-Stahl E, Stierner U, Solberg A, Langberg C, Bremnes RM, Laurell A, Wijkstrøm H, Klepp O. Risk-adapted treatment in clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer: the SWENOTECA management program. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009 May 1:27(13):2122-8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8953. Epub 2009 Mar 23

[PubMed PMID: 19307506]

[74]

Stephenson AJ, Bosl GJ, Bajorin DF, Stasi J, Motzer RJ, Sheinfeld J. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in patients with low stage testicular cancer with embryonal carcinoma predominance and/or lymphovascular invasion. The Journal of urology. 2005 Aug:174(2):557-60; discussion 560

[PubMed PMID: 16006891]

[75]

Diagnostic aspects of pleural effusion., Ayvazian LF,, Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 1977 Jul-Aug

[PubMed PMID: 15837993]

[76]

Stephenson AJ, Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ, Bajorin DF, Stasi JP, Sheinfeld J. Nonrandomized comparison of primary chemotherapy and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection for clinical stage IIA and IIB nonseminomatous germ cell testicular cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2007 Dec 10:25(35):5597-602

[PubMed PMID: 18065732]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[77]

Classen J, Schmidberger H, Meisner C, Souchon R, Sautter-Bihl ML, Sauer R, Weinknecht S, Köhrmann KU, Bamberg M. Radiotherapy for stages IIA/B testicular seminoma: final report of a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003 Mar 15:21(6):1101-6

[PubMed PMID: 12637477]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[78]

Schmidberger H, Bamberg M, Meisner C, Classen J, Winkler C, Hartmann M, Templin R, Wiegel T, Dornoff W, Ross D, Thiel HJ, Martini C, Haase W. Radiotherapy in stage IIA and IIB testicular seminoma with reduced portals: a prospective multicenter study. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1997 Sep 1:39(2):321-6

[PubMed PMID: 9308934]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[79]

Garcia-del-Muro X,Maroto P,Gumà J,Sastre J,López Brea M,Arranz JA,Lainez N,Soto de Prado D,Aparicio J,Piulats JM,Pérez X,Germá-Lluch JR, Chemotherapy as an alternative to radiotherapy in the treatment of stage IIA and IIB testicular seminoma: a Spanish Germ Cell Cancer Group Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 Nov 20;

[PubMed PMID: 18936476]

[80]

Heidenreich A, Paffenholz P, Nestler T, Pfister D, Daneshmand S. Role of primary retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in stage I and low-volume metastatic germ cell tumors. Current opinion in urology. 2020 Mar:30(2):251-257. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000736. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 31972635]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[81]

Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bokemeyer C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Fizazi K, Horwich A, Laguna MP, Nicolai N, Oldenburg J, European Association of Urology. Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2015 Update. European urology. 2015 Dec:68(6):1054-68. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.07.044. Epub 2015 Aug 18

[PubMed PMID: 26297604]

[82]

Oldenburg J, Fosså SD, Nuver J, Heidenreich A, Schmoll HJ, Bokemeyer C, Horwich A, Beyer J, Kataja V, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Testicular seminoma and non-seminoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2013 Oct:24 Suppl 6():vi125-32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt304. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 24078656]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[83]

Albers P,Siener R,Kliesch S,Weissbach L,Krege S,Sparwasser C,Schulze H,Heidenreich A,de Riese W,Loy V,Bierhoff E,Wittekind C,Fimmers R,Hartmann M,German Testicular Cancer Study Group., Risk factors for relapse in clinical stage I nonseminomatous testicular germ cell tumors: results of the German Testicular Cancer Study Group Trial. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003 Apr 15

[PubMed PMID: 12697874]

[84]

. International Germ Cell Consensus Classification: a prognostic factor-based staging system for metastatic germ cell cancers. International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1997 Feb:15(2):594-603

[PubMed PMID: 9053482]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[85]

Culine S, Kramar A, Théodore C, Geoffrois L, Chevreau C, Biron P, Nguyen BB, Héron JF, Kerbrat P, Caty A, Delva R, Fargeot P, Fizazi K, Bouzy J, Droz JP, Genito-Urinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers Trial T93MP. Randomized trial comparing bleomycin/etoposide/cisplatin with alternating cisplatin/cyclophosphamide/doxorubicin and vinblastine/bleomycin regimens of chemotherapy for patients with intermediate- and poor-risk metastatic nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: Genito-Urinary Group of the French Federation of Cancer Centers Trial T93MP. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 Jan 20:26(3):421-7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.8461. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18202419]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[86]

Feldman DR, Lorch A, Kramar A, Albany C, Einhorn LH, Giannatempo P, Necchi A, Flechon A, Boyle H, Chung P, Huddart RA, Bokemeyer C, Tryakin A, Sava T, Winquist EW, De Giorgi U, Aparicio J, Sweeney CJ, Cohn Cedermark G, Beyer J, Powles T. Brain Metastases in Patients With Germ Cell Tumors: Prognostic Factors and Treatment Options--An Analysis From the Global Germ Cell Cancer Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2016 Feb 1:34(4):345-51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.7000. Epub 2015 Oct 12

[PubMed PMID: 26460295]

[87]

Doyle DM, Einhorn LH. Delayed effects of whole brain radiotherapy in germ cell tumor patients with central nervous system metastases. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2008 Apr 1:70(5):1361-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.11.005. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18374223]

[88]

Herr HW, Sheinfeld J, Puc HS, Heelan R, Bajorin DF, Mencel P, Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ. Surgery for a post-chemotherapy residual mass in seminoma. The Journal of urology. 1997 Mar:157(3):860-2

[PubMed PMID: 9072586]

[89]

Sheinfeld J, Bajorin D. Management of the postchemotherapy residual mass. The Urologic clinics of North America. 1993 Feb:20(1):133-43

[PubMed PMID: 8381994]

[90]

Albany C, Kesler K, Cary C. Management of Residual Mass in Germ Cell Tumors After Chemotherapy. Current oncology reports. 2019 Jan 21:21(1):5. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0758-6. Epub 2019 Jan 21

[PubMed PMID: 30666469]

[91]

Cheng L, Zhang S, Eble JN, Beck SD, Foster RS, Wang M, Ulbright TM. Molecular genetic evidence supporting the neoplastic nature of fibrous stroma in testicular teratoma. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 2012 Oct:25(10):1432-8. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.99. Epub 2012 Jun 8

[PubMed PMID: 22684226]

[92]

Brandli DW, Ulbright TM, Foster RS, Cummings OW, Zhang S, Sweeney CJ, Eble JN, Cheng L. Stroma adjacent to metastatic mature teratoma after chemotherapy for testicular germ cell tumors is derived from the same progenitor cells as the teratoma. Cancer research. 2003 Sep 15:63(18):6063-8

[PubMed PMID: 14522936]

[93]

Ehrlich Y, Brames MJ, Beck SD, Foster RS, Einhorn LH. Long-term follow-up of Cisplatin combination chemotherapy in patients with disseminated nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: is a postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection needed after complete remission? Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Feb 1:28(4):531-6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0714. Epub 2009 Dec 21

[PubMed PMID: 20026808]

[94]

Kollmannsberger C, Daneshmand S, So A, Chi KN, Murray N, Moore C, Hayes-Lattin B, Nichols C. Management of disseminated nonseminomatous germ cell tumors with risk-based chemotherapy followed by response-guided postchemotherapy surgery. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Feb 1:28(4):537-42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0755. Epub 2009 Dec 21

[PubMed PMID: 20026807]

[95]

Lakes J, Lusch A, Nini A, Albers P. Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in the setting of elevated markers. Current opinion in urology. 2018 Sep:28(5):435-439. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000535. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30004909]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[96]

Loehrer PJ Sr, Einhorn LH, Williams SD. VP-16 plus ifosfamide plus cisplatin as salvage therapy in refractory germ cell cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1986 Apr:4(4):528-36

[PubMed PMID: 3633952]

[97]

Nichols CR, Catalano PJ, Crawford ED, Vogelzang NJ, Einhorn LH, Loehrer PJ. Randomized comparison of cisplatin and etoposide and either bleomycin or ifosfamide in treatment of advanced disseminated germ cell tumors: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, Southwest Oncology Group, and Cancer and Leukemia Group B Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1998 Apr:16(4):1287-93

[PubMed PMID: 9552027]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[98]

. Ongoing Clinical Trials in Testicular Cancer: The TIGER Trial. Oncology research and treatment. 2016:39(9):553-6. doi: 10.1159/000448868. Epub 2016 Sep 8

[PubMed PMID: 27614956]

[99]

Sharp DS,Carver BS,Eggener SE,Kondagunta GV,Motzer RJ,Bosl GJ,Sheinfeld J, Clinical outcome and predictors of survival in late relapse of germ cell tumor. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2008 Dec 1

[PubMed PMID: 18936477]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[100]

Oing C, Seidel C, von Amsberg G, Oechsle K, Bokemeyer C. Pharmacotherapeutic treatment of germ cell tumors: standard of care and recent developments. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2016:17(4):545-60. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2016.1127357. Epub 2015 Dec 31

[PubMed PMID: 26630452]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[101]

Kondagunta GV, Bacik J, Donadio A, Bajorin D, Marion S, Sheinfeld J, Bosl GJ, Motzer RJ. Combination of paclitaxel, ifosfamide, and cisplatin is an effective second-line therapy for patients with relapsed testicular germ cell tumors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Sep 20:23(27):6549-55

[PubMed PMID: 16170162]

[102]

Adra N, Abonour R, Althouse SK, Albany C, Hanna NH, Einhorn LH. High-Dose Chemotherapy and Autologous Peripheral-Blood Stem-Cell Transplantation for Relapsed Metastatic Germ Cell Tumors: The Indiana University Experience. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017 Apr 1:35(10):1096-1102. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.5395. Epub 2016 Nov 21

[PubMed PMID: 27870561]

[103]

Grogg JB, Schneider K, Bode PK, Kranzbühler B, Eberli D, Sulser T, Beyer J, Lorch A, Hermanns T, Fankhauser CD. Risk factors and treatment outcomes of 239 patients with testicular granulosa cell tumors: a systematic review of published case series data. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology. 2020 Nov:146(11):2829-2841. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03326-3. Epub 2020 Jul 27

[PubMed PMID: 32719989]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[104]

Aydin AM, Zemp L, Cheriyan SK, Sexton WJ, Johnstone PAS. Contemporary management of early stage testicular seminoma. Translational andrology and urology. 2020 Jan:9(Suppl 1):S36-S44. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.09.32. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 32055484]

[105]

Kvammen Ø, Myklebust TÅ, Solberg A, Møller B, Klepp OH, Fosså SD, Tandstad T. Causes of inferior relative survival after testicular germ cell tumor diagnosed 1953-2015: A population-based prospective cohort study. PloS one. 2019:14(12):e0225942. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225942. Epub 2019 Dec 18

[PubMed PMID: 31851716]

[106]

Aass N, Fosså SD, Høst H. Acute and subacute side effects due to infra-diaphragmatic radiotherapy for testicular cancer: a prospective study. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 1992:22(5):1057-64

[PubMed PMID: 1555953]

[107]

Fosså SD, Horwich A, Russell JM, Roberts JT, Cullen MH, Hodson NJ, Jones WG, Yosef H, Duchesne GM, Owen JR, Grosch EJ, Chetiyawardana AD, Reed NS, Widmer B, Stenning SP. Optimal planning target volume for stage I testicular seminoma: A Medical Research Council randomized trial. Medical Research Council Testicular Tumor Working Group. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1999 Apr:17(4):1146

[PubMed PMID: 10561173]

[108]

Adra N, Einhorn LH. Testicular cancer update. Clinical advances in hematology & oncology : H&O. 2017 May:15(5):386-396

[PubMed PMID: 28591093]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[109]

Gilligan TD, Seidenfeld J, Basch EM, Einhorn LH, Fancher T, Smith DC, Stephenson AJ, Vaughn DJ, Cosby R, Hayes DF, American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline on uses of serum tumor markers in adult males with germ cell tumors. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010 Jul 10:28(20):3388-404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4481. Epub 2010 Jun 7

[PubMed PMID: 20530278]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[110]

Krege S, Beyer J, Souchon R, Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, Bamberg M, Bodrogi I, Bokemeyer C, Cavallin-Ståhl E, Classen J, Clemm C, Cohn-Cedermark G, Culine S, Daugaard G, De Mulder PH, De Santis M, de Wit M, de Wit R, Derigs HG, Dieckmann KP, Dieing A, Droz JP, Fenner M, Fizazi K, Flechon A, Fosså SD, del Muro XG, Gauler T, Geczi L, Gerl A, Germa-Lluch JR, Gillessen S, Hartmann JT, Hartmann M, Heidenreich A, Hoeltl W, Horwich A, Huddart R, Jewett M, Joffe J, Jones WG, Kisbenedek L, Klepp O, Kliesch S, Koehrmann KU, Kollmannsberger C, Kuczyk M, Laguna P, Galvis OL, Loy V, Mason MD, Mead GM, Mueller R, Nichols C, Nicolai N, Oliver T, Ondrus D, Oosterhof GO, Paz-Ares L, Pizzocaro G, Pont J, Pottek T, Powles T, Rick O, Rosti G, Salvioni R, Scheiderbauer J, Schmelz HU, Schmidberger H, Schmoll HJ, Schrader M, Sedlmayer F, Skakkebaek NE, Sohaib A, Tjulandin S, Warde P, Weinknecht S, Weissbach L, Wittekind C, Winter E, Wood L, von der Maase H. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus Group (EGCCCG): part II. European urology. 2008 Mar:53(3):497-513. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.12.025. Epub 2007 Dec 26

[PubMed PMID: 18191015]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[111]

Warde P, Specht L, Horwich A, Oliver T, Panzarella T, Gospodarowicz M, von der Maase H. Prognostic factors for relapse in stage I seminoma managed by surveillance: a pooled analysis. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2002 Nov 15:20(22):4448-52

[PubMed PMID: 12431967]

[112]

Chung P, Daugaard G, Tyldesley S, Atenafu EG, Panzarella T, Kollmannsberger C, Warde P. Evaluation of a prognostic model for risk of relapse in stage I seminoma surveillance. Cancer medicine. 2015 Jan:4(1):155-60. doi: 10.1002/cam4.324. Epub 2014 Sep 19

[PubMed PMID: 25236854]

[113]

Dunphy CH,Ayala AG,Swanson DA,Ro JY,Logothetis C, Clinical stage I nonseminomatous and mixed germ cell tumors of the testis. A clinicopathologic study of 93 patients on a surveillance protocol after orchiectomy alone. Cancer. 1988 Sep 15;

[PubMed PMID: 2842034]

[114]

Daugaard G, Gundgaard MG, Mortensen MS, Agerbæk M, Holm NV, Rørth MR, von der Maase H, Jarle Christensen I, Lauritsen J. Surgery After Relapse in Stage I Nonseminomatous Testicular Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Jul 10:33(20):2322. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.2177. Epub 2015 Jun 1

[PubMed PMID: 26033809]

[115]

Gilbert DC, Al-Saadi R, Thway K, Chandler I, Berney D, Gabe R, Stenning SP, Sweet J, Huddart R, Shipley JM. Defining a New Prognostic Index for Stage I Nonseminomatous Germ Cell Tumors Using CXCL12 Expression and Proportion of Embryonal Carcinoma. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2016 Mar 1:22(5):1265-73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1186. Epub 2015 Oct 9

[PubMed PMID: 26453693]

[116]

Orre IJ, Fosså SD, Murison R, Bremnes R, Dahl O, Klepp O, Loge JH, Wist E, Dahl AA. Chronic cancer-related fatigue in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2008 Apr:64(4):363-71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.01.002. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18374735]

[117]

Mykletun A,Dahl AA,Haaland CF,Bremnes R,Dahl O,Klepp O,Wist E,Fosså SD, Side effects and cancer-related stress determine quality of life in long-term survivors of testicular cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 May 1;

[PubMed PMID: 15860864]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[118]

Weijl NI, Rutten MF, Zwinderman AH, Keizer HJ, Nooy MA, Rosendaal FR, Cleton FJ, Osanto S. Thromboembolic events during chemotherapy for germ cell cancer: a cohort study and review of the literature. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2000 May:18(10):2169-78

[PubMed PMID: 10811682]

[119]

Wiechno P, Demkow T, Kubiak K, Sadowska M, Kamińska J. The quality of life and hormonal disturbances in testicular cancer survivors in Cisplatin era. European urology. 2007 Nov:52(5):1448-54

[PubMed PMID: 17544206]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[120]

Fung C, Fossa SD, Williams A, Travis LB. Long-term Morbidity of Testicular Cancer Treatment. The Urologic clinics of North America. 2015 Aug:42(3):393-408. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2015.05.002. Epub 2015 Jun 10

[PubMed PMID: 26216826]

[121]

Zaid MA,Gathirua-Mwangi WG,Fung C,Monahan PO,El-Charif O,Williams AM,Feldman DR,Hamilton RJ,Vaughn DJ,Beard CJ,Cook R,Althouse SK,Ardeshir-Rouhani-Fard S,Dinh PC,Sesso HD,Einhorn LH,Fossa SD,Travis LB, Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors for Adverse Metabolic Outcomes in North American Testicular Cancer Survivors. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network : JNCCN. 2018 Mar;

[PubMed PMID: 29523664]

[122]

Fung C, Sesso HD, Williams AM, Kerns SL, Monahan P, Abu Zaid M, Feldman DR, Hamilton RJ, Vaughn DJ, Beard CJ, Kollmannsberger CK, Cook R, Althouse S, Ardeshir-Rouhani-Fard S, Lipshultz SE, Einhorn LH, Fossa SD, Travis LB, Platinum Study Group. Multi-Institutional Assessment of Adverse Health Outcomes Among North American Testicular Cancer Survivors After Modern Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2017 Apr 10:35(11):1211-1222. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.3108. Epub 2017 Feb 27

[PubMed PMID: 28240972]

[123]

Gilligan T. Quality of life among testis cancer survivors. Urologic oncology. 2015 Sep:33(9):413-9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2015.05.018. Epub 2015 Jun 15

[PubMed PMID: 26087970]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[124]

Kier MG, Hansen MK, Lauritsen J, Mortensen MS, Bandak M, Agerbaek M, Holm NV, Dalton SO, Andersen KK, Johansen C, Daugaard G. Second Malignant Neoplasms and Cause of Death in Patients With Germ Cell Cancer: A Danish Nationwide Cohort Study. JAMA oncology. 2016 Dec 1:2(12):1624-1627. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3651. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27711914]

[125]

Travis LB,Fosså SD,Schonfeld SJ,McMaster ML,Lynch CF,Storm H,Hall P,Holowaty E,Andersen A,Pukkala E,Andersson M,Kaijser M,Gospodarowicz M,Joensuu T,Cohen RJ,Boice JD Jr,Dores GM,Gilbert ES, Second cancers among 40,576 testicular cancer patients: focus on long-term survivors. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005 Sep 21;

[PubMed PMID: 16174857]

[126]

Fosså SD, Gilbert E, Dores GM, Chen J, McGlynn KA, Schonfeld S, Storm H, Hall P, Holowaty E, Andersen A, Joensuu H, Andersson M, Kaijser M, Gospodarowicz M, Cohen R, Pukkala E, Travis LB. Noncancer causes of death in survivors of testicular cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007 Apr 4:99(7):533-44

[PubMed PMID: 17405998]

[127]

Fung C, Fossa SD, Milano MT, Sahasrabudhe DM, Peterson DR, Travis LB. Cardiovascular Disease Mortality After Chemotherapy or Surgery for Testicular Nonseminoma: A Population-Based Study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2015 Oct 1:33(28):3105-15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3654. Epub 2015 Aug 3

[PubMed PMID: 26240226]

[128]

Mehta A, Sigman M. Management of the dry ejaculate: a systematic review of aspermia and retrograde ejaculation. Fertility and sterility. 2015 Nov:104(5):1074-81. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.024. Epub 2015 Oct 1

[PubMed PMID: 26432530]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[129]

Cullen M,Steven N,Billingham L,Gaunt C,Hastings M,Simmonds P,Stuart N,Rea D,Bower M,Fernando I,Huddart R,Gollins S,Stanley A, Antibacterial prophylaxis after chemotherapy for solid tumors and lymphomas. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Sep 8;

[PubMed PMID: 16148284]

[130]

Baniel J, Sella A. Complications of retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in testicular cancer: primary and post-chemotherapy. Seminars in surgical oncology. 1999 Dec:17(4):263-7

[PubMed PMID: 10588855]

[131]

Heidenreich A, Thüer D, Polyakov S. Postchemotherapy retroperitoneal lymph node dissection in advanced germ cell tumours of the testis. European urology. 2008 Feb:53(2):260-72

[PubMed PMID: 18045770]

[132]

Wood HM, Elder JS. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: separating fact from fiction. The Journal of urology. 2009 Feb:181(2):452-61. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.074. Epub 2008 Dec 13

[PubMed PMID: 19084853]