Introduction

The superficial musculoaponeurotic system, or SMAS, is often described as an organized fibrous network composed of the platysma muscle, parotid fascia, and fibromuscular layer covering the cheek. This system divides the face's deep and superficial adipose tissue and has region-specific morphology. Anatomically, the SMAS lies inferior to the zygomatic arch and superior to the platysma's muscular belly.

The fibromuscular layer of the SMAS integrates with the superficial temporal fascia and frontalis muscle superiorly and platysma inferiorly. The SMAS may even be described as a fibrous degeneration of the platysma itself. In reality, a precise anatomical definition of the SMAS is unclear and has been thoroughly debated since Mitz and Peyronie first described this fibromuscular network in 1976.[1]

The SMAS is a key structure involved in facial aging. Understanding the anatomy and dynamics of the SMAS is critical for healthcare providers specializing in facial rejuvenation procedures.

Structure and Function

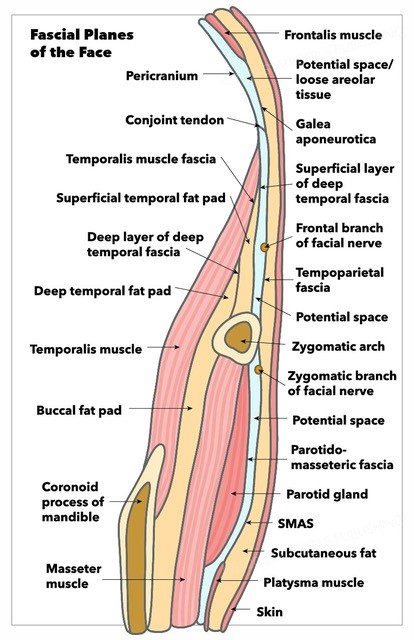

The SMAS can be considered an aponeurotic 'mask' overlying the key mimetic facial muscles. This structure comprises 1 of the 5 facial layers (see Image. Fascial Planes of the Face):

- Layer 1: Skin, which has the epidermis and dermis

- Layer 2: Subcutaneous fat

- Layer 3: Musculoaponeurotic, comprised of the SMAS and facial muscles

- Layer 4: Loose areolar tissue or deep fat

- Layer 5: Periosteum and deep fascia

The SMAS is thus uniquely positioned to reflect facial movements and expressions.[2]

The SMAS' key anatomical boundaries are the zygomatic arch superiorly and the platysma inferiorly.[3] Directly anterior to the SMAS is the face's subcutaneous superficial fatty tissue. Directly deep to the SMAS is the parotidomasseteric fascia, though a potential space exists between these 2 layers.

The SMAS is not uniform across its breadth. Cadaveric dissection studies reveal 2 SMAS types occurring in distinct facial areas. Type 1 SMAS lies in the region lateral to the nasolabial fold (NLF). Type 2 SMAS is medial to the NLF. These 2 SMAS areas primarily differ in their cellular architecture and underlying structures. Type 1 SMAS overlies the key facial expression muscles and is composed of large fat lobules entwined in a fibrous septal network. This area is relatively loose, enabling mobility of the underlying muscles. On the other hand, type 2 SMAS has scarce fat cells and is thus denser, creating a more rigid connection to the underlying tissue.[4]

The SMAS connects the facial muscles to the dermis. This fibromuscular structure transmits, distributes, and amplifies the activity of all facial muscles.[5] The SMAS is closely related to the face and neck's most superficial fascial planes. Macchi et al describe the SMAS as a central tendon that allows coordinated facial muscular contraction vital to producing facial expressions.[6][7]

Embryology

The superficial facial musculature originates from the 2nd arch mesenchyme, which migrates during development and forms a premuscular lamina. This premuscular lamina ultimately gives rise to the mandibular, temporal, infraorbital, and cervical laminae during the 8th week of embryogenesis. The platysma originates from a part of the cervical lamina, which encloses the inferior aspects of the parotid gland and cheek. The SMAS derives from the area superior to this lamina.[8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The SMAS receives blood from the transverse facial artery, which also supplies blood to a broad region of the lateral malar area. This vessel travels directly through the SMAS. Thus, SMAS elevation has an increased risk of transverse facial artery transection. SMAS elevation is a key step in facelift surgeries (rhytidectomies) and facial reconstruction following parotidectomy.[9] The SMAS also partially receives circulation from the musculocutaneous perforators of the facial artery.[10]

The small lymphatic vessels deep to the SMAS mainly flow into the preauricular or submandibular lymph nodes, which then drain into the anterior cervical chain. The anterior cervical nodes, which lie close to the anterior jugular vein, drain to the deep cervical chain near the internal jugular vein before emptying into the mediastinum.[11]

Nerves

The SMAS is mainly innervated by the facial nerve (CN VII). This nerve exits the skull inferior to the ear tragus. The facial nerve's proximal branches—the temporal, zygomatic, and marginal mandibular nerves—travel deep to the SMAS after exiting the parotid gland. The zygomatic and superior masseteric retaining ligaments form a groove through which the facial nerve's superior zygomatic branch traverses.[12]

The great auricular nerve supplies the inferolateral SMAS. This nerve originates from the cervical plexus, passes inferiorly to the sternocleidomastoid muscle about 6 cm inferior to the auditory canal, and runs deep to the SMAS along the external jugular vein.

The trigeminal nerve's sensory branches are the only nerves coursing superficially to the SMAS.

Muscles

The SMAS is prominent in the buccal, temporal, zygomatic, and platysma regions (see Image. Muscular and Fibrous Structures of the Head, Face, and Neck). Thus, the corresponding muscles can serve as the SMAS' anatomical landmarks. The SMAS lies directly anterior to the parotid gland and masseter, a key mastication muscle possessing superficial and deep parts.[13] The superficial segment originates from the zygomatic bone's maxillary process and inferior zygomatic arch border. The deep masseter layer originates from the inferior zygomatic arch surface. The masseter's 2 parts form a common insertion at the mandibular angle's lateral surface.

The parotid gland lies inferior to the zygomatic arch and extends posteriorly to the external auditory meatus and mandibular ramus. The masseter is anterior to this gland.[14] The parotid is invested by a fascia separated from the SMAS by a layer of intervening fat.[15]

The SMAS additionally invests smaller and more intricate muscles, which include the following:

- Orbicularis oculi

- Orbicularis oris

- Occipitofrontalis

- Levator labii superioris

The orbicularis oculi are divided into orbital and palpebral sections, which attach to the periorbital region. The orbital section of this muscle inserts medially on the medial canthal tendon and laterally to the lateral palpebral raphe. This muscle segment likewise interdigitates superiorly with the frontalis muscle.[16] The palpebral section of the orbicularis oculi is further subdivided into preseptal and pretarsal sections. The preseptal portion attaches to the lacrimal sac and associated fascia, while the pretarsal segment inserts on the anterior and posterior lacrimal crests.

The orbicularis oris muscle was previously considered a sphincter-like structure surrounding the mouth. This muscle's deep fibers bilaterally originate from the modiolus—the fibrous confluence of the facial muscles.[17]

The orbicularis oris' superficial fibers originate directly from other muscles of facial expression: the depressor anguli oris, zygomaticus major, zygomaticus minor, levator labii superioris, levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, and transversus nasi.[18] The dynamics between the SMAS and these underlying facial muscles are critical factors in forming facial expressions and treating facial aging signs.

The forehead, nasolabial folds, and nasal regions are usually not covered by the SMAS, although anatomical variants may involve these muscles.

Physiologic Variants

Studies about SMAS physiologic variants are limited. Khawaja et al referred to this musculoaponeurotic network as the "superficial musculoaponeurotic fatty system" (SMAFS) in their study of 800 facelift procedures. The authors found that 6 SMAFS variants existed based on fatty layer composition: membranous, fatty, mixed, island, fleshy, and fibrous.

Some SMAFS variants may be due to congenital anomalies, atrophy, injuries from repeated botox injections, and steroid use. Variants of this musculoaponeurotic layer were found to impact the surgical approaches taken and facelift surgery outcomes. Operative techniques like plicating, lifting, debulking, and attachment to the bony periosteum must be appropriate for the SMAFS variant to enhance the odds of cosmetic and surgical success.

Surgical Considerations

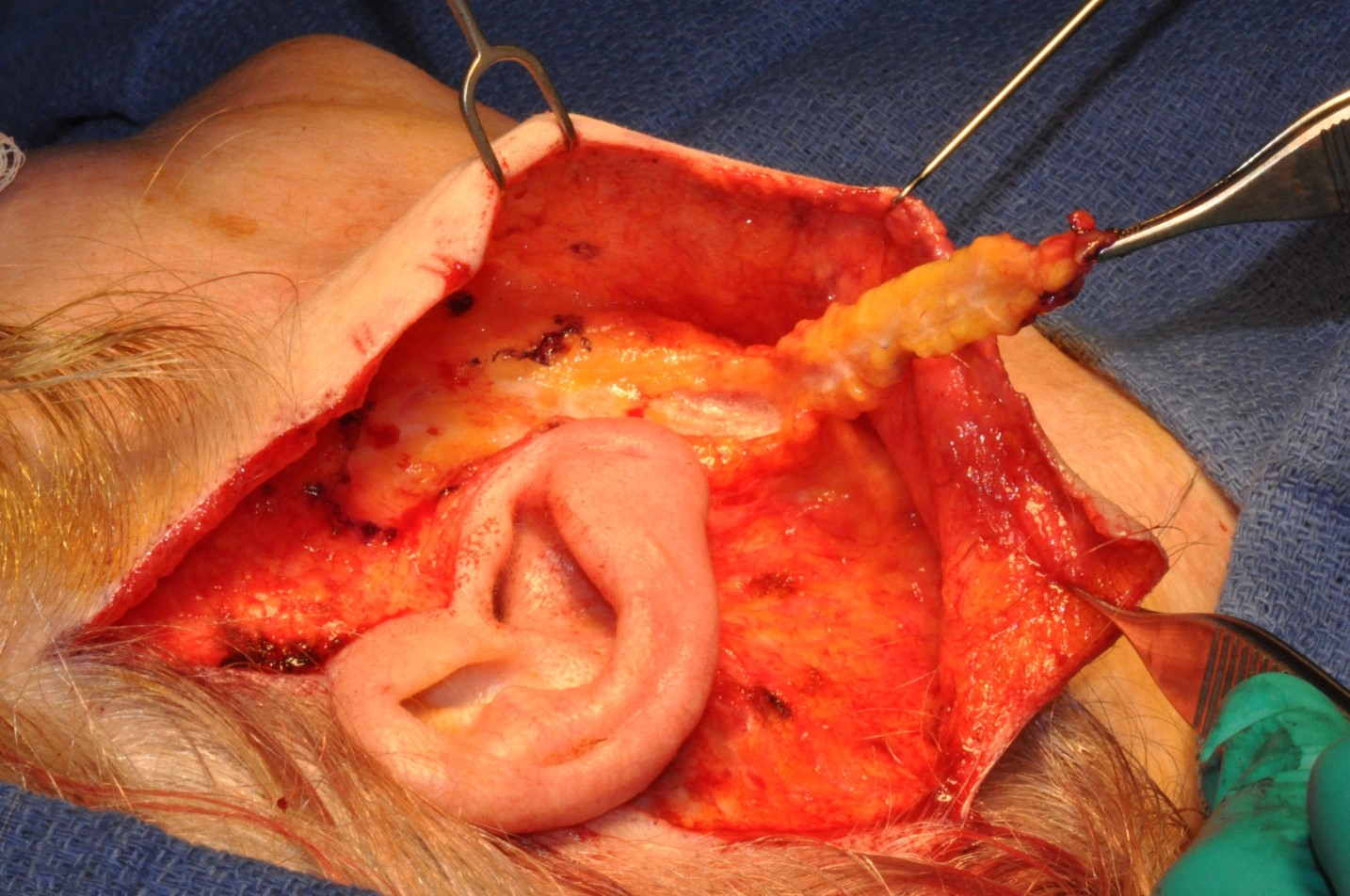

Surgical SMAS maneuvering and tightening allow for complete facial rejuvenation, hence the layer's importance in rhytidectomy, also known as "facelift." Rhytidectomies entail elevating the SMAS to reverse age-related superficial dermal, fat, and muscular drooping (see Image. Result of a Deep-Plane Facelift). Case reports suggest that 50% of all rhytidectomies involve at least some type of SMAS manipulation and dissection, underscoring this fibromuscular layer's importance in such procedures.[19][20][21] However, SMAS manipulation is more valuable in enhancing the face's lower third than the midface (see Image. SMAS Flap).

Neuromodulator infiltration, as in botulinum toxin treatment, achieves results similar to rhytidectomies. Neuromodulator injection is a non-invasive procedure that tightens the mimetic facial muscles and directly alters the conformational shape of the overlying SMAS. Patients may prefer this treatment over rhytidectomy because it often requires a shorter recovery time and is less expensive.

Clinical Significance

Pathological processes affecting the SMAS include denervation and subsequent atrophy, as in Bell palsy, myasthenia gravis, and myotonic dystrophy. Infection, trauma, and neoplasms like lymphoma, adenoid cystic carcinomas, and dermoid cysts may also alter the tissue composition and quality in this layer. Regular self-skin examination can help patients treat many of these conditions in their early stages and minimize SMAS damage.

Other Issues

Numerous attempts have been made to provide a clearer SMAS anatomical definition. However, inconsistencies in basic terminology and the SMAS' anatomical location and general morphology have made it difficult to achieve this goal. Some researchers even doubt the existence of this musculoaponeurotic network and its relationship to the zygomaticus muscle, parotid fascia, or NLF. Still, recent studies concur that the SMAS is an entirely separate layer superficial to the parotid gland and parotidomasseteric fascia. Additionally, most agree that the SMAS is continuous with the NLF, even the orbicularis oris, to some extent.[22]