Continuing Education Activity

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) manifests as a rare primary perforating dermatosis, showcasing distinct transepidermal elimination of modified collagen across the epidermis. This condition typically appears in 2 distinct forms: a seldom-seen hereditary variant emerging in childhood and an acquired variant, more prevalent among adults with diabetes mellitus or end-stage renal disease. Predominantly found on the extensor regions of limbs and hands, hyperkeratotic papules develop, often triggered by superficial traumas. These intensely pruritic lesions evolve into sizable umbilicated papulonodules characterized by a central keratotic plug, displaying periods of relapse and remission across the patient's lifespan.

Although the majority of cases of RPC are self-limiting and generally do not necessitate therapeutic intervention, the condition poses considerable discomfort due to its pruritic nature and the development of pronounced papulonodules. This activity reviews the etiology, assessment, and management of RPC, including dermatological monitoring and symptomatic relief through emollients or topical steroids. Learners will understand how a tailored approach to managing underlying comorbidities, particularly diabetes mellitus or end-stage renal disease, might be essential to alleviating the incidence and severity of RPC symptoms in affected individuals. This session also covers the importance of an interprofessional team managing treatment, patient education, and follow-up care.

Objectives:

Identify the pathophysiology of reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC), distinguishing between the acquired adult-onset and inherited childhood-onset forms of RPC, noting associations with diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease.

Recognize the hallmark presentation of RPC, including hyperkeratotic papules on limb extensor areas, particularly noting the association with superficial trauma and the condition's recurrent nature.

Apply evidence-based therapeutic approaches for managing RPC symptoms, considering individual patient characteristics and comorbidities.

Commuicate the need for a well-integrated, interprofessional team approach to improve care for patients with RPC.

Introduction

Reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC), one of the perforating dermatoses, is a rare skin disease with a characteristic transepidermal elimination of altered collagen through the epidermis. It occurs in 2 forms: an inherited form in childhood that is rare and an acquired form in adulthood, more commonly found in patients with diabetes mellitus and end-stage renal disease.[1][2] Commonly, patients will have hyperkeratotic papules on the extensor areas of extremities and hands, most likely over areas of superficial trauma. The lesions are very pruritic and can grow into large, umbilicated papulonodules with a central keratotic plug that relapse and remit throughout the patient’s lifetime. Most cases are self-limited and do not require treatment.[3][4]

Etiology

The precise etiology and pathogenesis of RPC are unknown. The inherited form has had reported cases of autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, and sporadic inheritance. It has been proposed that superficial trauma, genetic predisposition, microvasculopathy, and calcium deposits in the skin may contribute to the development of RPC. Experimental production of the classic RPC lesion has been reported with a needle scratch.[5]

Epidemiology

RPC is a rare inherited disease. Fewer than 50 cases have been reported in the literature since it was first described in 1967. The acquired form found in adults is more common and can occur in approximately 10% of renal patients on hemodialysis. RPC shows no racial predilection, although it has been noted that 3 of the 5 cases of the giant variant of acquired RPC have been found in Asians. Inherited and acquired RPC have been found equally in males and females. Most commonly, the inherited form presents in infancy or childhood, whereas the acquired form occurs in adults from their third to their fifth decade of life.[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Although no specific cause or genetic defect has been found for RPC, the transepidermal elimination of collagen could be caused by a simple reaction from pruritus or a defect in collagen, leading to focal damage. Serum and tissue concentrations of fibronectin have been reported to be elevated in RPC, which may contribute to epithelial migration. Superficial trauma, as well as a cold environment, induces the degeneration of collagen. It has also been reported that the receptor for advanced glycation end products may play a role in the pathogenesis of acquired RPC. This receptor plays a role in the inflammatory response pathway as a multiligand transmembrane receptor.

Histopathology

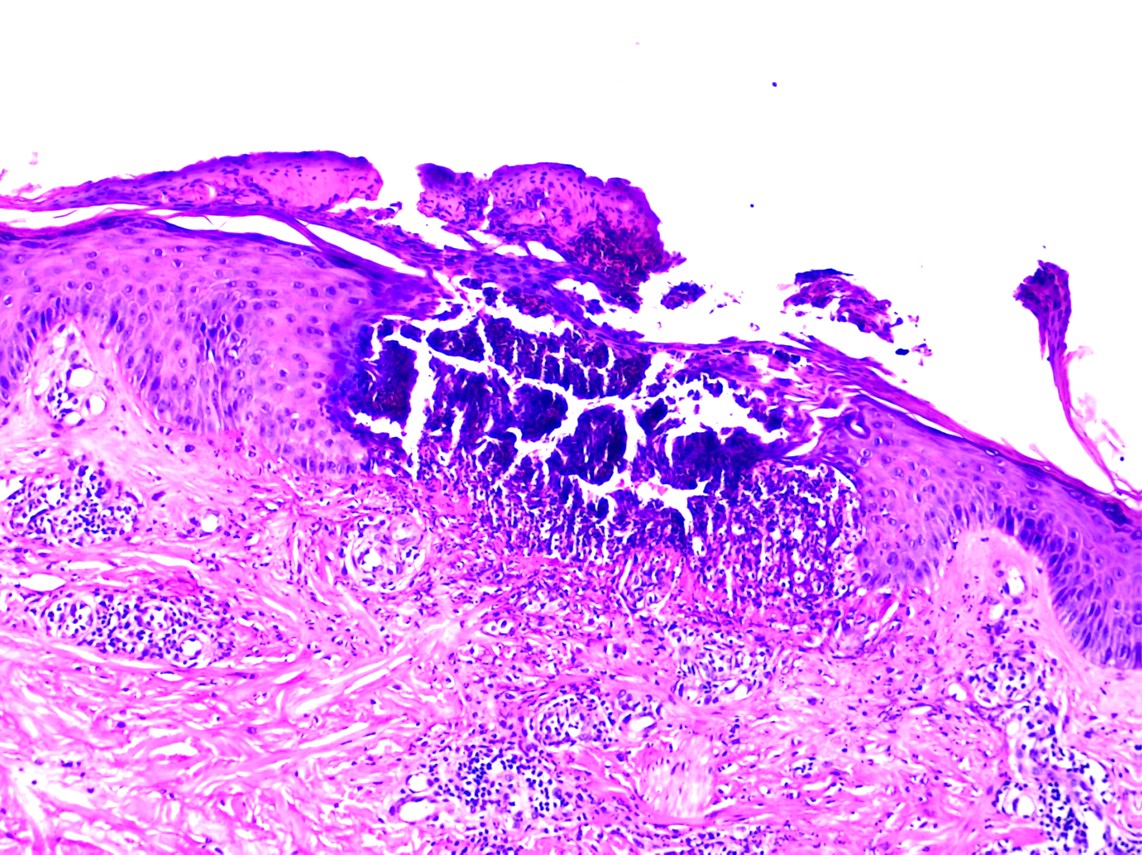

Classically, the histology of RPC is transepidermal. Vertically oriented, cup-shaped invagination of the epidermis is most commonly seen. Vertically oriented perforating bundles of basophilic collagen are present at the bases of the invagination of the epidermis with focal extrusions. A keratin plug is most likely found in the cupping of the epidermis. Histology is variable depending on the stage of the lesion. New lesions will show epidermal hyperplasia and degenerated basophilic collagen fibers, with later lesions showing invagination of the epidermis with a keratin plug.

Although the diagnosis can be made with hematoxylin and eosin stain (H&E) histopathology, special stains are important in dermatology conditions and can be used to diagnose RPC. Collagen is extruded through the epidermis in RPC and can be stained with Masson's trichrome, Verhoeff-van Gieson, aldehyde fuchsin, phosphotungstic acid-hematoxylin (PTAH) or Movat's pentachrome.

The vertically oriented basophilic collagen fibers are highlighted with Verhoeff-Van Gieson staining, which stains the collagen fibers red. This differentiates RPC from elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) because collagen fibers appear red in RPC, and elastic fibers appear black in EPS. However, in EPS, the elastic fibers higher up in the epidermis may lose their ability to stain black. Masson trichome–stained collagen will appear blue-green. Aldehyde fuchsin stains collagen fibers red, just as Verhoeff-Van Gieson does.

History and Physical

The small, hyperkeratotic papules of RPC can be present in any area of the body. The inherited form begins in infancy as papules located on the extensor surfaces of the hands, elbows, and knees, most likely after superficial trauma to the area. RPC lesions grow into larger, umbilicated papulonodules with central adherent keratin plugging. The lesions commonly resolve spontaneously in 6 to 8 weeks, leaving a hyperpigmented area or scar.

Patients with RPC will most likely complain of pruritus of the lesions. Koebner phenomenon of the lesions can occur. Most patients will experience a relapsing and remitting course of the disease. Five cases of a giant variant of acquired RPC have been reported. In one case, a 60-year-old woman on hemodialysis presented with 1- to 10-cm papules with a central keratotic plug that showed transepidermal elimination of collagen on histology.[8][9][10][11]

Evaluation

A diagnosis of RPC is made based on the recognition of consistent histologic findings (collagen extruding through the epidermis) and consistent clinical features (keratotic papules or umbilicated papulonodules). A punch biopsy typically provides a sufficient specimen for histopathologic examination. There is no genetic test for RPC; however, a positive family history offers additional support for this diagnosis. The dermoscopic features of RPC include a yellow-brown structureless area in the center of the lesion matching the central crust, with a white rim of variable thickness around the central crust indicating keratinous debris, and an outer pink circle with short looped and peripheral dotted vessels corresponding with dermal inflammation.

Treatment / Management

RPC lesions are commonly self-limited and rarely problematic. The mainstay of treatment is avoiding trauma to decrease risk factors for acquiring RPC lesions. Treatment is also aimed at controlling pruritus with topical corticosteroids, emollients, and systemic antihistamines. The use of keratolytics, topical and oral retinoids, phototherapy, liquid nitrogen, methotrexate, and allopurinol have been reported without much improvement of the lesions.

No randomized controlled trials have evaluated the treatments for RPC, and all treatment suggestions result from case reports. It appears that treatment is patient-specific and can vary with the degree of severity of the lesions. Most lesions will regress spontaneously in 6 to 8 weeks with hypopigmentation, scarring, or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Unfortunately, most patients will have a relapsing and remitting course of lesions throughout their life.[11][12]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for RPC include:

- Folliculitis: The presence of pustules with a central hair protruding and inflamed papules in a hair-bearing site distinguishes folliculitis from RPC. Moreover, a biopsy would demonstrate inflammatory cells in the follicular wall and ostia instead of the transepidermal elimination of collagen seen in RPC.

- Prurigo nodularis: The lesions are usually more nodular; upon histopathology, they demonstrate compact hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, and a perivascular inflammatory infiltrate with thickened dermal collagen.

- Multiple keratoacanthomas: These lesions are more crater-like than RPC lesions; histologically, they demonstrate a central core of keratin and mild pleomorphism with a well-differentiated squamous epithelium.

- Dermatofibroma: These lesions usually occur as solitary, firm, flesh-colored nodules, commonly on the lower extremities, with distinguished spindle cell proliferation with trapped collagen on histology.

- Arthropod bites: These bites lack an umbilicated center clinically and demonstrate eosinophilic infiltrates on histology.

- Other primary perforating dermatoses: These include kyrle disease, perforating folliculitis, and elastosis perforans seriginosa.

- Secondary perforating disorders: These include lichen nitidus, granuloma annulare, and chromoblastomycosis.

Prognosis

The inherited form of RPC often persists into adulthood and may cause some residual scarring; however, the prognosis for the acquired form is generally optimistic. Some patients note improvement in pruritus and diminishing skin lesions with the treatment of the underlying systemic disease. Many patients, however, may experience a recurrence once treatment is withdrawn.

Complications

Chronic itching has a negative impact on the quality of life of the patients and predisposes their skin to secondary bacterial infection. Healing of individual lesions leads to scarring and dyspigmentation in all skin types.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

RPC is a rare benign skin disorder. When the primary care provider, nurse practitioner, and internist see patients with skin disorders, they should be referred to a dermatologist to confirm the diagnosis. The mainstay of treatment is avoiding trauma to decrease risk factors for acquiring RPC lesions. Treatment is also aimed at controlling pruritus with topical corticosteroids, emollients, and systemic antihistamines. Using keratolytics, topical and oral retinoids, phototherapy, liquid nitrogen, methotrexate, and allopurinol has been reported without much improvement of the lesions.

No randomized controlled trials have evaluated the treatments for RPC, and all treatment suggestions result from case reports. Unfortunately, most patients will have a relapsing and remitting course of lesions. Typically, these patients are managed chronically by a dermatologist, nurse practitioner, or nurse specializing in dermatology. The patients require regular follow-up visits, close monitoring, and education regarding the disease process and treatment. Generally, the nurse practitioner and nurse can manage follow-up and involve the dermatologist if there are concerns, such as a disease progression or the pruritis becoming intractable. The best care for these patients to produce the best outcome is an interprofessional team managing treatment, patient education, and follow-up.