Continuing Education Activity

A pneumothorax is an accumulation of gas in the pleural space (the space between the visceral and parietal pleura of the chest cavity), which can impair ventilation, oxygenation, or both. This condition can vary in its presentation from asymptomatic to life-threatening. This activity outlines the evaluation and management of patients presenting with acute pneumothorax and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in managing patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the most common presenting symptoms in a patient with an acute pneumothorax.

- Outline the treatment strategy for a patients with an acute pneumothorax.

- List the differential diagnosis for an acute pneumothorax.

- Employ an interprofessional team approach to provide optimal care to patients diagnosed with an acute pneumothorax.

Introduction

Pneumothorax - is an accumulation of air or gas in the pleural space (the space between visceral and parietal pleura of the chest cavity), which can impair with ventilation, oxygenation, or both. This condition can vary in its presentation from asymptomatic to life-threatening.[1][2]

Pneumothorax can subdivide into three broad categories according to the etiology:

1. Traumatic - resulting from blunt or penetrating chest trauma. Majority of all pneumothoraces are traumatic in origin

2. Iatrogenic - caused by manipulation by a healthcare provider, such as the insertion of central lines, etc

3. Spontaneous - a pneumothorax without any apparent cause or inciting event.

Pneumothorax can also be classified based on their physiology into the following types:

1. Simple - when the air in the pleural space does not communicate with an outside atmosphere, and there is no shift in mediastinum or hemidiaphragm. An example is a pleural laceration from a fractured rib.

2. Communicating - when there is a defect in a chest wall, such as from a gunshot wound, that causes open communication with an outside atmosphere. This loss of the chest wall integrity can create an air sucking and a paradoxical lung collapse, thus causing significant ventilatory problems.

3. Tension - progressive accumulation of air in the pleural cavity causing the shift of mediastinum to the opposite side, resulting in compression of vena cava and other great vessels, decreased diastolic filling, and ultimately compromised cardiac output. It occurs when a chest injury causes a one-valve situation when the air gets into the pleural cavity but is unable to escape freely and thus gets trapped.

Etiology

Causes:

1. Traumatic - results from blunt or penetrating injuries to the chest wall.

2. Spontaneous - primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in people with no underlying lung disease or inciting event, secondary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in people with significant underlying parenchymal lung disease and results from some inciting incident, such as a bleb rupture.[3]

3. Iatrogenic - is a subtype of traumatic pneumothorax, where an injury occurs as a result of a diagnostic or therapeutic medical intervention (i.e., insertion of a central line, etc.)

4. Catamenial - is a non-traumatic pneumothorax that occurs in women in conjunction with their menstrual period. Although not entirely understood, the cause is believed to be endometriosis of the pleura.

Epidemiology

The incidence of non-traumatic pneumothorax is 7.4 to 18 per 100000 people per year. [4] It is much higher in smokers (12% vs. 0.1% lifetime risk)[5]

Primary spontaneous pneumothorax often affects young males, tall and thin built, often smokers. The incidence of recurrence is 20 to 60% in the first 3 years after the first episode.

Secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces also occur in patients with underlying lung disease; thus epidemiology varies greatly.

Catamenial pneumothorax affects young women of childbearing age.

History and Physical

The clinical presentation varies depending on the etiology and the size of the pneumothorax. Some patients may be asymptomatic, and pneumothorax is diagnosed as an incidental finding during the workup for another condition.

The most common presenting symptoms are chest pain and shortness of breath (64 to 85%). Chest pain is usually severe, sharp/stabbing, pleuritic and radiates to ipsilateral shoulder/arm. Symptomatic onset is sudden, and in primary spontaneous pneumothorax can decrease after 24 hours, possibly due to gradual spontaneous resolution of the pneumothorax. Patients can also present with anxiety and cough, but these symptoms are less common. The patient may have a normal physical exam if the pneumothorax is small. However, with large enough pneumothorax, there may be absent breath sounds on the affected side. Many patients with first time spontaneous pneumothorax do not seek medical help for several days.

The signs and symptoms of tension pneumothorax are more severe, and timely diagnosis and treatment are crucial for the patient's survival. Tension pneumothorax, besides chest pain and shortness of breath, presents with hemodynamic compromise. The patient may have profound hypoxia and hypotension. The gradual accumulation of air in the pleural space due to one-valve situation causes the shift of the mediastinum to the contralateral side and compression of vena cava and eventual compromise of the cardiac output, producing life-threatening hypotension and hypoxia. On physical exam, the patient has absent breath sounds on the affected hemithorax, tracheal deviation to the contralateral side, tachycardia, and jugular venous distention — undiagnosed and untreated tension pneumothorax results in hemodynamic collapse and death.

Evaluation

Traumatic pneumothorax must be a suspected diagnosis in any blunt or penetrating chest trauma. Adequate history, physical exam and chest X-rays are the mainstays of the diagnosis. However, small pneumothoraces are often missed on physical exam and chest X-ray and may be present on CT chest during a diagnostic workup for other injuries.[6][1]

In patients who present with sudden onset of sharp pleuritic chest pain and shortness of breath, spontaneous pneumothorax should always be on a differential diagnosis list.[3]

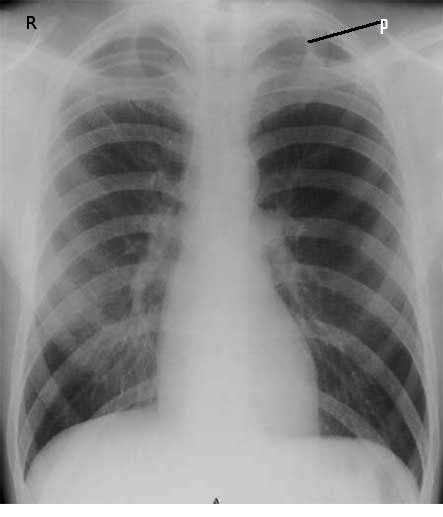

The diagnosis is often made by upright chest radiograph, except tension pneumothorax which is a clinical diagnosis.

Point of care ultrasound is commonly used in the evaluation patients with pneumothorax. In fact, ultrasound can rapidly diagnosis pneumothoraces with better accuracty than standard chest X-ray, while sparing the patient radiation expsoure. [7]

The definition of large vs. small pneumothorax is by the distance between the lung margin and chest wall[8]:

- Small pneumothorax: the presence of a visible rim of less than 2 cm between the lung margin and the chest wall

- Large pneumothorax: the presence of a visible rim of greater than 2 cm between the lung margin and the chest wall

The chest radiograph is thought to underestimate the size of pneumothorax.

Treatment / Management

The management is guided by the etiology, clinical presentation, and risk stratification.[3][6]

The principles of treatment of pneumothorax: air elimination, reduction of air leakage, healing of pleural fistula, promoting re-expansion of the lung, prevention of future recurrences.[9]

Asymptomatic patients with pneumothorax as an incidental finding may not need any intervention unless an estimated risk of recurrence is high. Typically this decision is not made initially in the emergency department, and a patient must obtain a referral to a pulmonologist for further evaluation and care.

Symptomatic patients with stable vital signs may require needle aspiration or small bore catheter insertion (pigtail catheter) in the emergency department. Evidence suggests that in a primary spontaneous pneumothorax needle aspiration is as safe and effective as tube thoracostomy.[10] These patients require admission for high flow oxygen and observation with interval repeat of the chest radiograph.

Generally, traumatic pneumothoraces with stable or unstable vital signs require the insertion of large vs. small bore thoracostomy catheter. Most of them can be treated with small bore pigtail catheters, although very large pneumothoraces may require treatment with large bore chest tubes.[11] If there is a concomitant hemothorax, a thoracostomy with a large bore chest tube insertion is necessary.

Pharmacotherapy:

In the treatment of pneumothorax, the pharmacotherapy is mainly focused on an adequate control of pain from the pneumothorax itself and/or from procedures to restore lung volumes and air-free pleural space (thoracostomy or needle aspiration). Pain control is achievable through local infiltration of an anesthetic at the thoracostomy site, as well as intravenous and oral pain medication administration, or both. Typically, a thoracostomy requires IV opiates or procedural sedation analgesia for the insertion of the tube and to manage the pain associated with the indwelling thoracostomy catheter. Some authors advocate for regional anesthesia for these patients, such as intercostal nerve blocks. Prophylactic antibiotics should be considered in patients during the chest tube insertion to prevent infection at the site of insertion and later complications, such as emphysema.

In patients with recurrent pneumothoraces, chemical pleurodesis, or sclerotherapy with talc may be a treatment consideration.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of non-traumatic spontaneous pneumothorax includes: pneumonia, acute asthma exacerbation, bronchitis, pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, costochondritis, acute coronary syndrome, anxiety or panic attack, diaphragmatic injuries, GERD, esophageal spasm, Mallory-Weiss tear, Boerhaave's syndrome, mediastinitis, myocarditis, pericarditis, pleurodynia, tuberculosis, pulmonary empyema, lung abscess.

In traumatic pneumothoraces, tension pneumothorax and concomitant hemothorax must always be considered. There is a high association of other traumatic injuries in the chest and abdomen in patients with traumatic pneumothorax. Therefore, an appropriate full trauma evaluation must be completed by emergency physicians and trauma surgeons to exclude other injuries.

Prognosis

Spontaneous pneumothorax has a recurrence rate close to 20 to 60% in the next 3 years after the initial episode.[12]

Complications

Misdiagnosis is a frequent complication of pneumothorax. Multiple factors, such as incomplete or inadequate history or physical exam, low index of clinical suspicion, failure to obtain a chest radiograph, or failure to recognize a pneumothorax on a chest radiograph, can contribute to misdiagnosis. Misdiagnosis leads to failure to treat the pneumothorax, and in some cases can lead to devastating consequences such as[9][13][14][15][16][15][14]:

- Conversion to tension pneumothorax

- Hypoxemic Respiratory Failure

- Shock

- Respiratory arrest

- Cardiac arrest

- Empyema

- Re-expansion pulmonary edema

- Iatrogenic complications from the needle decompression or thoracostomy procedure - the failure of the lung to re-expand, lung laceration, infection of the insertion site and pleural space, laceration of intercostal vessels or internal mammary artery, hemothorax, persistent air leak, damage to the intercostal neurovascular bundle, etc

- Chest tube-induced arrhythmia

- Pneumomediastinum - air from the pneumothorax can track into the mediastinum. This can be visualized on the chest X-ray as air leuncy around the heart. Additionally, a crunching sound may be asculated during the cardiac examination. This is called Hamman's crunch and is best heard in the left lateral decubitus position.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of a pneumothorax is with an interprofessional team that includes an emergency department physician, general surgeon, thoracic surgeon, critical care specialist, radiologist, and specialty-trained emergency or critical care nurse. After assisting with chest tube placement, the monitoring of these patients is performed by the nurses. Nurses must assess the wound site, breath sounds, and patency of the drainage system and report to the team any abnormalities. Further, sudden development of a tension pneumothorax can cause a rapid deterioration in a patient's overall clinical status. Hence prompt identification by the nurse followed by treatment by the interprofessional team is essential. The nurse is usually the first to identify the condition and must be prepared to contact the clinical team immediately and then assist in any rapid intervention. It is a prevalent condition with over 5 million patients admitted to the ICUs each year in the United States with pneumothorax. While a chest x-ray remains the standard modality for diagnosing a pneumothorax, numerous enhancements in radiology software have taken place over the last few years enabling easier diagnosis, especially for less experienced practitioners.[17] Having a trained interprofessional team managing the evaluation and treatment of a pneumothorax will result in the best outcomes. Lines of communication must be open and rapid. [Level V]