Continuing Education Activity

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is a minimally invasive procedure to open blocked or stenosed coronary arteries, allowing unobstructed blood flow to the myocardium. The blockages occur because of lipid-rich plaque within the arteries, diminishing blood flow to the myocardium. The accumulation of lipid-rich plaque in the arteries is known as atherosclerosis. The disorder is known as coronary artery disease caused by atherosclerosis affecting the coronary arteries. This activity describes the indications, contraindications, and complications of PTCA and highlights the interprofessional team's role in managing patients with CAD.

Objectives:

Identify the indications for PTCA.

Assess the contraindications for PTCA.

Evaluate the complications of PTCA.

Communicate the importance of improving care coordination among the interprofessional team to enhance care delivery for patients undergoing PTCA.

Introduction

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is a minimally invasive procedure to open blocked or stenosed coronary arteries, allowing unobstructed blood flow to the myocardium. The blockages occur because of lipid-rich plaque within the arteries, diminishing blood flow to the myocardium. The accumulation of lipid-rich plaque in the arteries is known as atherosclerosis. The disorder is known as coronary artery disease caused by atherosclerosis affecting the coronary arteries. Patients with CAD usually present with exertional chest pain or with dyspnea with exertion. In acute myocardial infarction, there is plaque rupture with platelet aggregation and acute thrombus formation, which results in a sudden occlusion of the coronary artery. These patients present with acute chest heaviness, diaphoresis, and nausea. Urgent PTCA is often required to limit myocardial damage.

Andreas Gruentzig first developed PCTA in 1977, and the procedure was performed in Zurich, Switzerland, that same year.[1] By the mid-1980s, many leading institutions had adopted this procedure worldwide to treat coronary artery disease. PTCA is a hallmark procedure and the basis of many other intracoronary interventions. It is 1 of the most common procedures in the United States, making up 3.6% of all operating room procedures performed in 2011.

Anatomy and Physiology

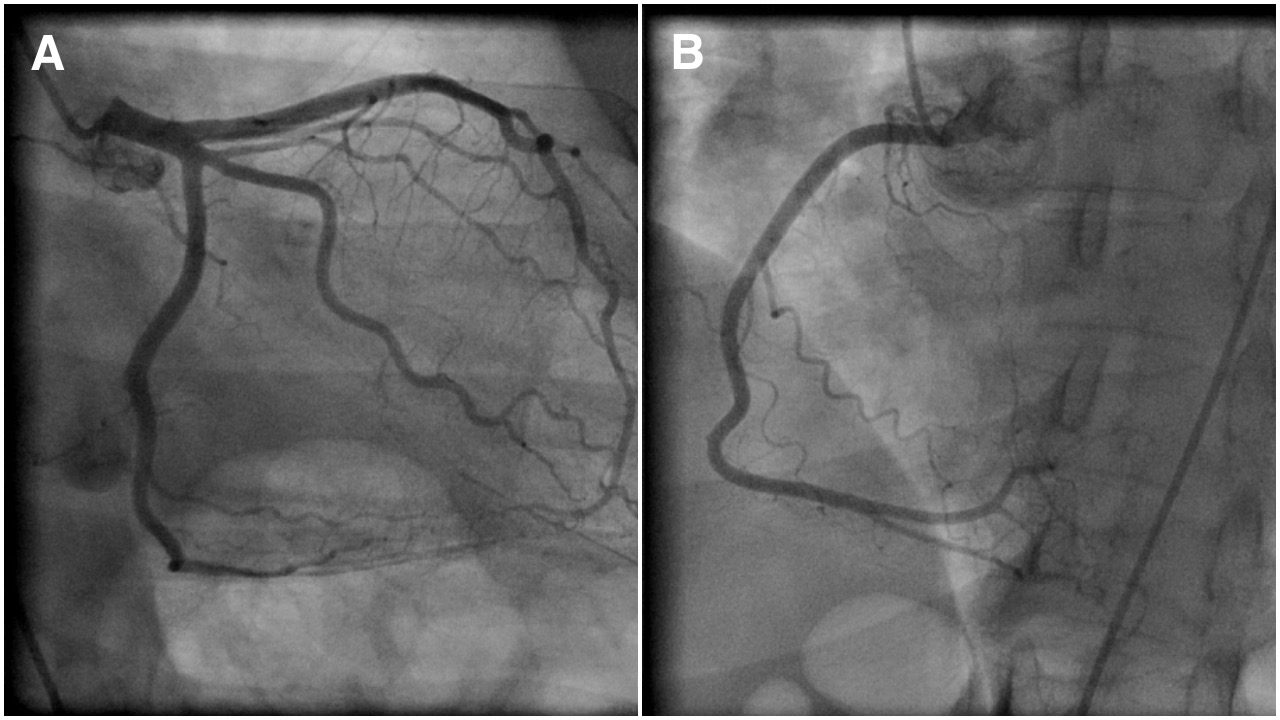

The 2, main coronary arteries supplying the heart are the right and left coronary arteries. The left coronary artery (LCA) divides into left anterior descending (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCX) branches. LCA supplies blood to the left ventricle of the heart. See Image. Coronary Angiogram Showing Normal Epicardial Left (A) and Right (B) Coronary Arteries. The right coronary artery (RCA) divides into the right posterior descending (PDA) and a (PL) posterolateral branch. RCA supplies blood to the ventricles, right atrium, and sinoatrial node. Coronary arteries are end-arteries supplying the myocardium, and blockage can lead to serious adverse effects. Coronary artery disease occurs due to plaque buildup within the coronary arteries, which reduces blood flow to the myocardium with subsequent narrowing and blockage.

Indications

Indications of PTCA depend on various factors. Patients with stable angina symptoms unresponsive to maximal medical therapy will benefit from PCI. It helps provide relief of persistent angina symptoms despite maximal medical therapy.[2] Emergency PTCA is indicated for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), suggesting 100% occlusion of the coronary artery. With acute STEMI, patients are taken directly to the cath lab immediately upon presentation to help prevent further myocardial muscle damage. In non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or unstable angina, (known as acute coronary syndromes), patients are taken to the cardiac cath lab within 24 to 48 hours.

Contraindications

PTCA has limited contraindications. Patients with left main CAD are poor candidates for the procedure due to the risk of acute obstruction or spasm of the left main coronary artery during the procedure. It is also not recommended for patients with hemodynamically insignificant (less than 70%) stenosis of the coronary arteries.

Equipment

Initially, PCI was performed using balloon catheters alone. However, other devices were introduced due to subclinical outcomes and vessel re-stenosis, including atherectomy devices and coronary stents. Atherectomy devices used alone resulted in poor outcomes. Coronary stents are the most widely used intracoronary devices in PTCA due to improved clinical outcomes. Various stents are available, including traditional bare-metal (BMS) and drug-eluting (DES). DES has a polymer coating that prevents inflammation and endothelial cell proliferation. Most recent DES used in the United States use sirolimus, everolimus, and zotarolimus. The newer generation DES has reduced the incidence of late stent thrombosis.[3] Antiplatelet therapy is important during the first 12 months after PTCA, allowing appropriate duration for endothelial cell formation over the metallic stent to prevent stent thrombosis.

Personnel

PTCA is performed by a team consisting of an interventional cardiologist, nurse, and radiology technologist. All team members must have extensive specialized training in the procedure.

Preparation

An interprofessional team evaluates the patients and performs pre-procedural testing to determine candidacy for the procedure. The inquiry about the history of allergy to seafood or contrast agents is vital. Important pre-procedure laboratory tests include PT and PTT, serum electrolytes, BUN, and creatinine. The patient is required to be well-hydrated. Medication review is essential, including cessation of anticoagulants if possible. Also, common medications, including NSAIDs or ACEIs, can be held to prevent worsening renal insufficiency. The diabetes medication metformin is held before cardiac catheterization to avoid worsening renal insufficiency and lactic acidosis. Fluids and food are restricted 6 to 8 hours before the procedure. When cases are performed via radial artery access, patients are often given intra-arterial calcium channel blockers, nitroglycerin, and heparin to prevent vasospasm. The health care provider should thoroughly explain the procedure and its associated risks and complications to the patient to obtain a signed informed consent.

Technique or Treatment

The procedure is performed under local anesthesia. Conscious sedation is routinely given to avoid stress and calm the patient. The most commonly used approach is the percutaneous femoral (Judkins) approach. Once the patient is anesthetized with a superficial injection of lidocaine to the skin and subcutaneous tissues over the right femoral artery, a needle is inserted into the femoral artery (percutaneous access). The insertion of a guidewire follows successful needle insertion through the needle into the lumen of the blood vessel. The needle is then removed with the guidewire remaining in the vessel lumen. A sheath with an introducer is placed over the guidewire and into the femoral artery. Next, the guidewire and introducer are removed, leaving the sheath in the vessel lumen. This provides easy access to the femoral artery lumen. Next, a long, narrow tube, known as the "diagnostic catheter," is advanced through the sheath with a long guidewire in the catheter lumen. The diagnostic catheter follows the guidewire and is passed retrograde through the femoral artery, iliac artery, descending aorta, and over the aortic arch to the proximal ascending aorta. The guidewire is removed, leaving the diagnostic catheter's tip in the ascending aorta. The diagnostic catheter is attached to a manifold with a syringe. The manifold allows for injecting contrast, checking inter-arterial pressure, and administering medications.

The diagnostic catheter is then manipulated into the ostium of the left main coronary artery or right coronary artery. Contrast dye is injected, and cineangiography images are obtained in multiple views of both arteries. PTCA can be performed if severe stenosis exists in 1 of the arteries. The diagnostic catheter is removed and exchanged for a similar guide catheter. Guide catheters have a larger luminal diameter to pass wires and balloons during angioplasty easily. After the guide catheter is placed in the ostium of the respective artery, a PTCA guidewire is advanced through the catheter and across the stenosis. Once the PTCA guidewire is passed across the stenosis, it is left in place until the end of the procedure. A balloon wire can be placed over the PTCA guidewire and advanced until the balloon is directly over the stenosis. The cardiologist controls the direction and movement of the PTCA guidewire and balloon wire by twisting the part of the guidewire that sits outside the patient.

The balloon is then inflated and deflated repeatedly until the artery is patent. In most instances, a stent is required. The balloon wire is removed and exchanged for a stent. A stent is a latticed metal scaffold delivered crimped over a balloon of balloon wire. The stent is then placed in the position of the stenosis, and the balloon is expanded. Once the stent is expanded, it cannot be removed from the artery. The balloon is deflated, and the stent remains in place. The stent can maintain long-term patency. Repeated injections of contrast media are utilized to check for artery patency. Upon successfully inserting the stent and expanding the vessel, the balloon wire is removed. Lastly, the PTCA guidewire is removed. During the procedure, anticoagulation is administered to prevent the formation of clots. Depending upon the technical difficulties of the case, the entire procedure can take from 30 minutes to 3 hours.

Complications

PTCA is widely practiced and has risks, but major procedural complications are rare. The mortality rate during angioplasty is 1.2%.[4] People older than the age of 65, with kidney disease or diabetes, women and those with massive heart disease are at a higher risk for complications. Possible complications include hematoma at the femoral artery insertion site, pseudoaneurysm of the femoral artery, infection of skin over the femoral artery, embolism, stroke, kidney injury from contrast dye, hypersensitivity to dye, vessel rupture, coronary artery dissection, bleeding, vasospasm, thrombus formation, and acute MI. There is a long-term risk of re-stenosis of the stented vessel.

Clinical Significance

PTCA is performed under local anesthesia and serves as an alternative to coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). Compared to CABG, PTCA is associated with lower morbidity and mortality, shorter recovery, and lower cost. It can significantly improve blood flow through the coronary arteries in about 90% of patients, with relief of anginal symptoms and improvement in exercise capacity. It effectively eliminates arterial narrowing in most cases. Different modeling studies presented different conclusions regarding the cost-effectiveness of PTCA and CABG in patients with myocardial ischemia who do not respond to medical therapy.[5][6][7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

PTCA is not an easy procedure; despite technological advances, it has risks and complications. All patients need to be educated about the procedure and its potential complications. Maintaining a healthy diet, exercising, and reducing stress are important post-procedural measures to reduce the risk of recurrences and complications. The heart team illustrates an excellent example of patient-centered care. Experts from different fields of medicine come together to provide the best solution for each patient.[8]