Introduction

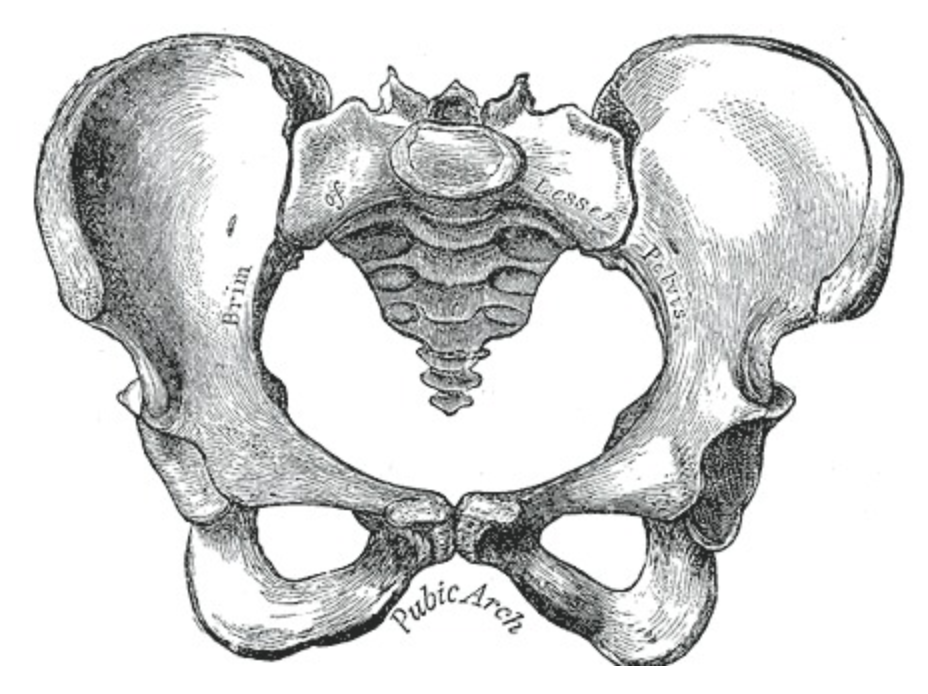

The pelvic outlet also called the inferior pelvic aperture, defines the lower margin of the lesser (true) pelvis. The pelvic cavity (the true pelvis) predominantly contains the urinary bladder, the colon, and the internal reproductive organs. This space is enclosed between the pelvic inlet and the pelvic outlet. The pelvic outlet is the inferior opening of the pelvis that is bounded by coccyx, the ischial tuberosities, and the pubis symphysis.

Structure and Function

The pelvic outlet is an approximately diamond-shaped space that marks the inferior margin of the true pelvis. This opening in the pelvis has boundaries that mirror the perineal triangle boundaries, as the two spaces share a common base.

Anatomic boundaries of the pelvic outlet:

- Anterior: inferior margin of the pubic symphysis

- Anteriolateral: inferior rami of the pubis and ischial tuberosities

- Posterolateral: inferior margins of the sacrotuberous ligaments

- Posterior: anterior border of the coccyx

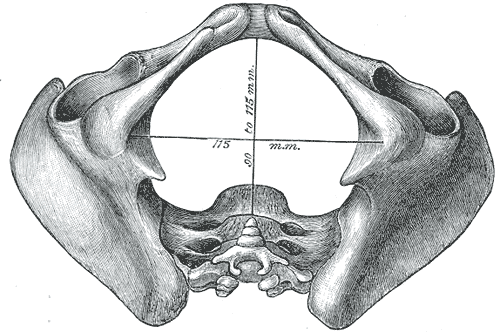

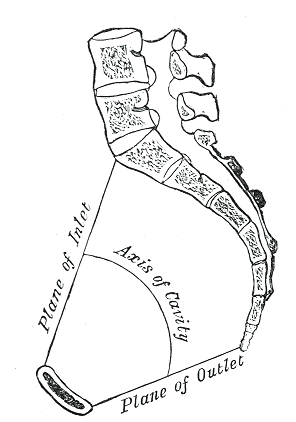

Three diameters can describe measurements of the pelvic outlet: anteroposterior, posterior sagittal, and transverse (intertuberous). The anteroposterior (AP) diameter, from the pubic symphysis to the sacrococcygeal joint, is the largest diameter of the pelvic outlet and typically measures between 9.5 to 12.5 cm. This measurement can vary widely due to the mobility of the coccyx. The transverse diameter, between the ischial tuberosities, is generally between 8 to 11 cm. In males, all measurements are slightly shorter relative to body size than in females. In females, these diameters are important in pelvimetry and have demonstrated to increase during labor to facilitate the delivery of a fetus through the pelvic outlet.[1][2]

The bony pelvis and the pelvic outlet have several functions. The pelvis provides protection for the internal pelvic organs contained within the pelvic cavity. The bony pelvis has many structural functions from a load-bearing perspective, supporting the weight of the body, stabilizing the upper trunk, and coordinating movements as the legs maneuver. Several ligaments join the bones of the pelvis and segment the openings within the bones, which aid in cushioning the weight of the body and allow for some mobility during the labor. The bony pelvis acts as the attachment site for several ligaments, trunk, and lower limb muscles. Foramens, or openings within the bony structure of the pelvis, permit passage of nerves and vasculature between the upper and lower body. The terminal segments of the vagina, the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts transverse the opening of the pelvic outlet. In females, the pelvic outlet also offers support and guidance for a fetus through the birth canal.[3]

Embryology

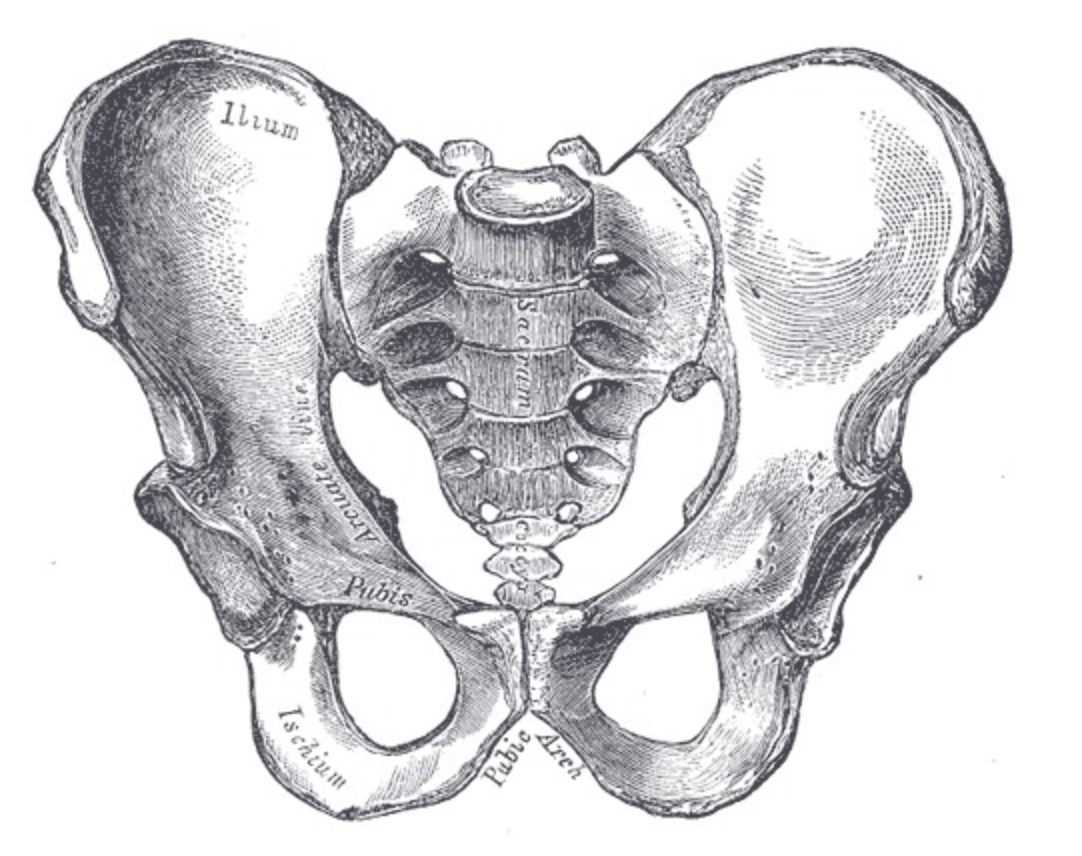

The formation of the pelvis requires a cascade of chondrification, ossification, and fusion. The earliest appendicular structures form at embryonic day 28. By the fifth week, the condensation of mesenchymal tissue in the limb buds form the template for bone models, and the ilium becomes recognizable by about five months prenatally. The pelvis forms via the process of endochondral ossification, where chondrocytes in cartilage stimulate mineralization and blood vessel growth. This ossification stems from three primary ossification centers termed the iliac center, ischial center, and pubic center. The primary ossification centers are well developed by birth, but the ossification process continues postnatally, slowing down after three months of age. Ontogeny of the pelvis is completed in adulthood, typically around 25 years of age. Sexual dimorphism of the pelvis is visually apparent in the ilium, the acetabulum, the iliac height, and the width of the pelvic inlet and outlet.[4][5][6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The common iliac artery bifurcates into the internal and external branches at the L5-S1 vertebral level. The internal iliac artery descends inferiorly through the pelvic inlet into the true pelvis. The internal iliac artery supplies the pelvic organs, perineal floor, and gluteal muscles with blood. At the superior border of the greater sciatic foramen, the internal iliac artery divides into an anterior and posterior trunk. The anterior trunk supplies the pelvic organs, the perineum, and the gluteal and adductor areas of the lower limb. The internal pudendal artery, which is a branch of the anterior trunk, travels through the lesser sciatic foramen and is the main blood supply to the perineum. The perineum is the space between the pelvic diaphragm and the pelvic outlet. The posterior trunk of the internal iliac artery supplies the posterior abdominal wall, posterior pelvis, and some of the gluteal region of the lower limb. The iliolumbar artery, which arises from the posterior trunk, ascends into the true pelvis and supplies the muscles and bones around the iliac fossa.[7]

There are four main groups of lymph nodes in the pelvis: the sacral, internal, external, and common iliac nodes. There are several smaller nodes within the pelvis, such as the pararectal, lumbar, superficial inguinal, and more. These pelvic lymph nodes receive afferent drainage from the pelvic, peripheral, visceral, and parietal structures. The external iliac nodes are along the pelvic brim and drain pelvic organs such as the bladder and the body of the uterus. The internal iliac nodes drain the lower rectum (above the pectinate line), part of the vagina, bladder, cervix, and prostate. The sacral lymph nodes are located in the concavity of the sacrum, and they drain lymph from the posteroinferior viscera. The common iliac nodes are located above the pelvis, but they receive drainage from all three other groups. The pelvic lymph nodes form a highly interconnected network. This arrangement is problematic because metastatic cancer can pass in nearly any direction between pelvic and abdominal organs.[8]

Nerves

The lumbosacral trunk (L4-S3), the sacral plexus, and coccygeal plexus all pass through the pelvic cavity. Numerous branching nerves innervate pelvic and perineal muscles. Additionally, there are parasympathetic and sympathetic innervations within the pelvis. Divisions of the pelvic splanchnic (parasympathetic), sacral splanchnic (sympathetic), and the inferior hypogastric plexuses also have branches that supply the viscera of the pelvis. While many nerves originate below the level of the pelvic brim, very few of these nerves pass through the pelvic outlet but, instead, exit through the many foramina within the pelvis or terminate within the true pelvis.

The pudendal nerve (S 2,3,4) is a paired nerve that branches off of the sacral plexus. This nerve travels out of the greater sciatic foramen, into the lesser sciatic foramen, through the pudendal canal (sometimes called Alcock’s canal), and into the perineum. The terminal branches of the pudendal nerve, the dorsal nerve, and inferior rectal nerve provide sensory and motor innervation to the perineum and external genitalia. A common procedure during obstetric and anorectal procedures uses local anesthesia to block the pudendal nerve. During this procedure, the clinician will typically approach transvaginally, passing through the pelvic outlet, and use the ischial spine as a landmark to then inject a local anesthetic into the pudendal nerve.[9][10]

Muscles

The pelvic outlet is an opening bounded by coccyx, the ischial tuberosities, and the pubis symphysis. The pelvic diaphragm borders the pelvic outlet. From anterior to posterior the pelvic floor muscles (PFM) of the pelvic diaphragm include:

- Piriformis

- Coccygeus

- Levator ani (iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis) [11]

Five main ligaments are relevant when discussing the pelvic outlet, four of which exist in pairs. These ligaments, amongst others, provide structural support and connection of various tissues in and around the pelvis. During pregnancy, these ligaments will soften to allow movement between the bones to accommodate the passage of the fetus. However, if the ligaments become too elastic or become overstretched, this may lead to pelvis girdle instability.

- Interpubic ligament (also called the arcuate ligament or inferior pubic ligament) at the pubic symphysis joins the left and right superior rami.

- Sacroiliac ligaments connect the sacrum and the ilium. This ligament is essential for the effective load transfer between the spine and lower extremities.

- Sacrococcygeal ligaments consist of ventral and dorsal parts that limit the movement between the sacrum and coccyx.

- Sacrotuberous ligaments are fan-shaped ligaments that course from the sacrum and the upper coccyx to the ischial tuberosity. These ligaments form the posterolateral border of the pelvic outlet.

- Sacrospinous ligaments are triangular bands of fibrous tissue that attaches the ischial spine to the sacrum and coccyx. This ligament divides the greater sciatic notch into the greater and lesser sciatic foramen.

Physiologic Variants

The many physiologic variations in the pelvis and pelvic outlet between individuals of the male and female sex relate to function and body mass. In males, the pelvic bones, such as the pubic rami, tend to be thicker and heavier. The female pelvis is comparatively wider and shallower than males, which can be demonstrated by the iliac crest that may reach the level of the L4 vertebrae in males but only reaches the L5 vertebrae in females. The angle of the pubic arch, sometimes called the subpubic angle, will also show physiologic variation. Males have an acute subpubic angle (<70 degrees), and females have an obtuse angle (>80 degrees). The anteroposterior diameter of the pelvic outlet varies greatly as male coccyx tends to curve sharply inward, but the female coccyx is relatively straight. The pelvic outlet in females is rounder and larger, with straighter ischial spines. The physiologic variations between sexes are visible as early as the fourth month of fetal life, and the differences are widely attributed to the female pelvic cavity being adapted for the passage of a fetus through a birth canal. Forensic pathologists and forensic anthropologists utilize these differences to determine the sex of skeletal remains accurately.[12]

The Caldwell-Malloy classification system is a common tool used to describe normal variants of the pelvis. These variants have not demonstrated any causation or correlation between a patient’s size or weight. Many pelvises are mixed type, a combination of types, not a single pure type. The mixed types derive their names from a convention where the posterior segment determines the type of pelvis, and the anterior segment determines the “tendency.”[13]

The four normal variants of pelvic shape according to Caldwell-Malloy classifications[7][13]:

- Gynaecoid

- This shape is the most common female pelvis shape with a wide interspinous distance that is ideal for vaginal delivery.

- Android

- This pelvic anatomy is the most common masculine pelvis shape with a curved coccyx, prominent ischial spines, short AP diameter, and heart-shaped inlet. Overall, the internal dimensions of the pelvic cavity and pelvic outlet are smaller, and therefore vaginal delivery is relatively difficult.

- Anthropoid

- This pelvic shape is common in men with an AP diameter greater than the transverse diameter. The inlet and outlet are ovoid-shaped, and thus, the shape is generally suitable for vaginal delivery.

- Platepelloid

- This pelvic shape is uncommon in both male and female patients. The short AP diameter and wide transverse diameter make vaginal delivery very difficult. This pelvic shape is commonly associated with the arrest of labor, and thus surgical interventions are likely needed.

Surgical Considerations

Normal variants of pelvic shape may make a vaginal delivery more difficult for some female patients. Clinicians should be prepared to undergo surgical interventions or cesarean deliveries for the best maternal-fetal outcomes. Childbirth may injure or stretch the muscles and ligaments that surround the pelvic outlet, such as the levator ani or pubococcygeus muscle. These injuries can increase the risk of pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. The terminal segments of the vagina, the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts transverse the opening of the pelvic outlet. Surgeons accessing the pelvic cavity through the pelvic outlet, such as during vaginal delivery or pudendal nerve block, should be aware of the path of these structures and the significant variations that may lead to complications. For example, some studies determined that the distance between the ureter and the cervix can vary from >2 cm apart to <0.5 cm, a difference that increased the risk of urethral injuries.[14][15]

Clinical Significance

In contrast to the pelvis inlet, the pelvic outlet can be estimated via a physical exam. The pelvic outlet is a principal component of pelvimetry. These measurements are useful when assessing the risk of labor arrest, cephalo-pelvic disproportion, or a fetus’s ability to navigate through the birth canal. However, pelvimetry has limited use as the female pelvic joints and ligaments slacken during labor. Clinical evidence indicates that pelvimetry does not change the management of pregnant patients, as all pregnant individuals should be allowed the trial of labor regardless of pelvimetry results.[16][17]

The clinician monitors the progress of labor by an examination of the cervix. Factors that should be observed and recorded during labor include cervical dilation, effacement, the position of the fetal head, and station. The station of the fetal head is a numerical scale that estimates the number of centimeters between the fetal head and the ischial spines. This metric marks the progression of labor as the fetus passes through the birth canal. The narrowest distance that the head of the child must pass through during vaginal birth is the interspinous distance, which typically measures around 10 centimeters, is called station 0. However, this space is not a fixed distance due to pubic symphysis loosening during labor. Station +3, when the leading portion of the fetal head is 5 cm inferior to the ischial spine, is approximately at the opening of the pelvic outlet. As the fetus moves through the birth canal, the widest diameter of the pelvic canal changes direction from a transverse direction in the pelvic inlet, to an anteroposterior diameter in the pelvic outlet. For this reason, the fetal head must rotate as it passes through the birth canal during labor.

Numerous issues during labor can occur due to the size of the birth canal compared with the size of the fetal head. The pelvic outlet may obstruct vaginal delivery; however, this tends to occur only in cases of rare but significant pelvic bony diseases. Fetal macrosomia, which correlates with maternal diabetes, may increase the risk that the fetus cannot fit through the pelvic outlet during vaginal delivery. Patients with gestational diabetes or maternal diabetes should be monitored carefully for fetal macrosomia and evaluated for risk of fetal demise during vaginal delivery. Shoulder dystocia results from the impaction of the fetal shoulders against the pelvic outlet. Following the delivery of the head, the anterior shoulder may become trapped behind the pubic symphysis. Complications may include fetal brachial plexus injuries, fetal hypoxia, fetal rib or clavicle fractures, umbilical cord compression, perineal lacerations, and postpartum hemorrhage. Several maneuvers and surgical interventions may be employed as needed to complete the delivery. The Gaskin maneuver, with the mother on all fours, widens the pelvic outlet and has been shown to allow successful delivery in up to 80% of cases.[18][19][20][21]

The pudendal vessels and nerves pass between the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments. The pudendal nerve can become trapped between these ligaments and cause pain while sitting, genital numbness, perineal pain, and both urinary and fecal incontinence. Using a pudendal nerve block can temporarily relieve pain due to pudendal nerve entrapment. During this procedure, the clinician injects a local anesthetic using the ischial spine as a landmark.

Pelvic ligaments and pelvic floor injuries may occur due to stretching and tearing during pregnancy, persistent high abdominal pressure, trauma, or falls. In these cases, there is a risk of pelvic organ prolapse. Pelvic organ prolapse is a disorder where one or more pelvic organs drop below their normal position, past the pelvic outlet in some cases. Prolapses are graded and classified by the organ or organs that descend from its expected position (uterine prolapse, cystocele, rectocele, enterocele). Symptoms may include a sensation of “fullness” or pressure in the pelvis that may get worse with standing or coughing, seeing or feeling a bulge out of the vagina, incontinence (fecal or urinary), or dyspareunia. Pessaries and Kegel exercises are non-surgical treatment options that can relieve symptoms or manage asymptomatic patients. If these conservative measures fail, surgical management can correct the defects. Transvaginal sacrospinous ligament fixation anchors the vaginal vault and has been shown to stabilize the pelvic organs and decrease reoccurrence.[22][23]

Other Issues

Abnormal variants of the pelvic outlet shape can be due to a variety of different causes. Rachitic pelvises, deformities caused by a vitamin D deficiency, tend to have a larger AP diameter of the inlet with an increased outlet size diameter. Asymmetric pelvises can be associated with poliomyelitis, scoliosis, ankylosing spondylitis, congenital defects, and more.