Introduction

The Organ of Corti is an inner ear organ located within the cochlea that contributes to audition. It includes 3 rows of outer hair cells and 1 row of inner hair cells. Vibrations caused by sound waves bend the stereocilia on these hair cells via an electromechanical force. The hair cells convert mechanical energy into electrical energy transmitted to the central nervous system via the auditory nerve to facilitate audition.

Structure and Function

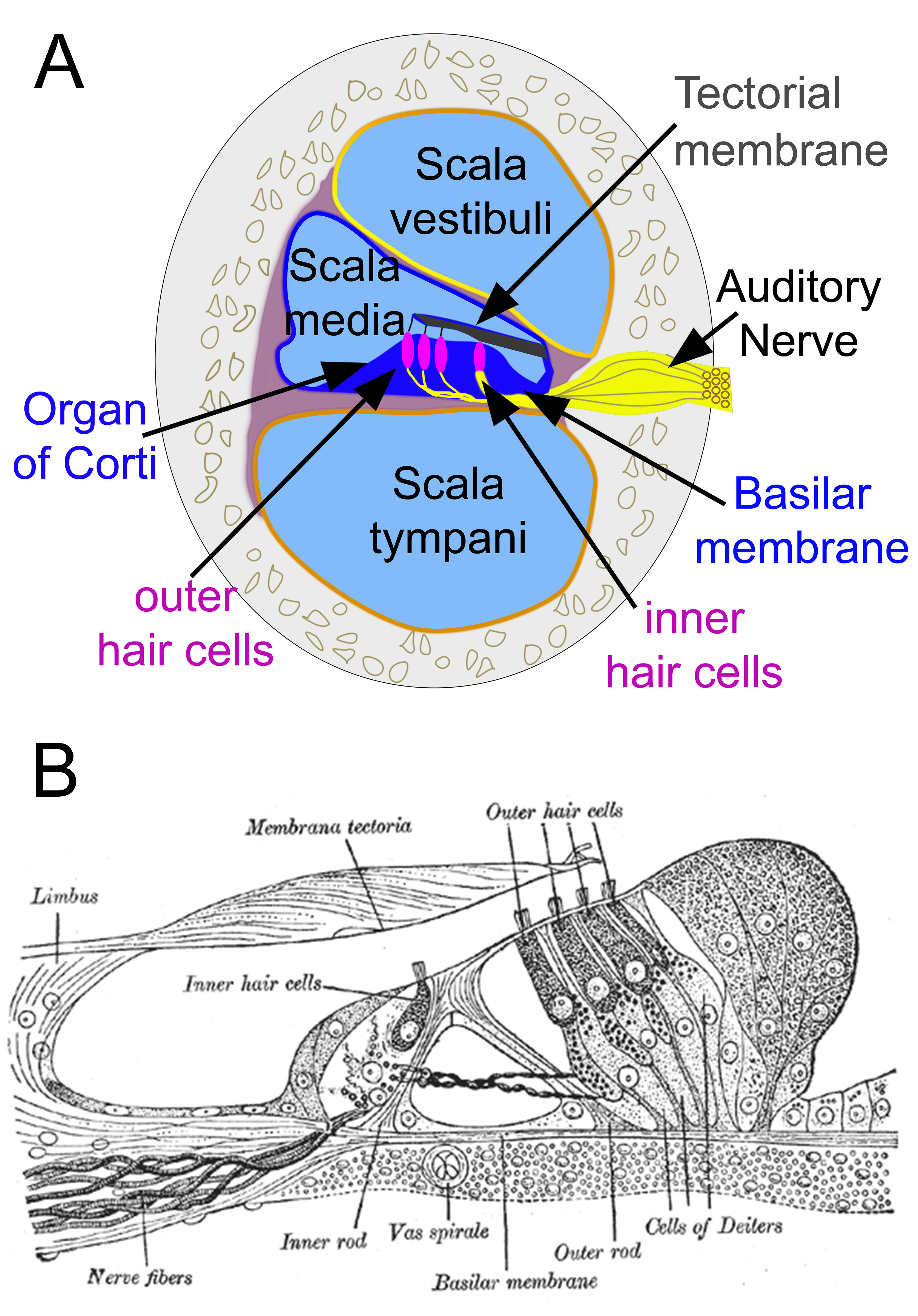

The primary function of the organ of Corti is the transduction of auditory signals. Sound waves enter the ear via the auditory canal and cause tympanic membrane vibration. Movement of the tympanic membrane causes subsequent vibrations within the ossicles, the 3 bones of the middle ear, which transfer the energy to the cochlea through the oval window. As the oval window moves, waves propagate through the perilymph fluid inside the scala tympani and then the scala vestibuli of the cochlea. When the fluid moves through these structures, the basilar membrane (located between the scala media and scala tympani) shifts to the tectorial membrane (see Image. Organ of Corti, A). The organ of Corti is an organ of the inner ear contained within the scala media of the cochlea. It resides on the basilar membrane, which separates the scala tympani and scala media. The scala media is a cavity within the cochlea containing endolymph with a high (150 mM) K+ concentration. The endolymph helps to regulate the electrochemical impulses of the auditory hair cells.[1]

The organ of Corti is composed of both supporting cells and mechanosensory hair cells. The arrangement of mechanosensory cells comprises inner and outer hair cells along rows (see Image. Organ of Corti, B). There is a single row of inner hair cells and 3 rows of outer hair cells, which are separated by the supporting cells. The supporting cells are also named Dieters' or phalangeal cells. The hair cells within the organ of Corti have stereocilia that attach to the tectorial membrane. Shifts between the tectorial and basilar membranes move these stereocilia and activate or deactivate the hair cell surface receptors. When cation channels open on the hair cells, potassium ions flow into the hair cells, the cells depolarize, and the depolarization causes voltage-gated calcium channels to open. The calcium influx releases glutamate from the hair cells into the auditory nerve. The auditory nerve then sends a stimulus from the sound wave to the brain, recognizing it as sound.

Inner hair cells function primarily as the sensory organs for audition. They provide input to 95% of the auditory nerve fibers that project to the brain.[1] The stiffness and size of the hair cell arrangement throughout the cochlea enable hair cells to respond to frequencies from low to high. Cells at the apex respond to lower frequencies, while hair cells at the base of the cochlea (near the oval window) respond to higher frequencies, which creates a tonotopic gradient throughout the cochlea.[2][1] While inner hair cells are the output center of the cochlea, the outer hair cells are the input center. They receive descending inputs from the brain to assist with the modulation of inner hair cell function (ie, modulating tuning and intensity information). Unlike other brain regions, the modulation of inner hair cells by outer hair cells is not electrical but mechanical. Activation of outer hair cells changes the stiffness of their cell bodies; this manipulates the resonance of perilymph fluid movement within the scala media and allows for fine-tuning of inner hair cell activation.[1]

Inner and outer hair cells are distinctly different in structure. Both hair cells have stereocilia on the apical surface; however, the arrangement of stereocilia and their connection to the tectorial membrane is distinctly different. For both types of hair cells, the mechanical bending of the stereocilia opens potassium channels at the tips of the stereocilia that allow hyperpolarization of the cells.[1] The tallest stereocilia of outer hair cells are embedded into the tectorial membrane. These stereocilia get displaced as the basilar membrane moves with the tectorial membrane. The stereocilia of inner hair cells are free-floating. Movement of the viscous perilymph fluid provides the mechanical force to open these channels.[1] Inner hair cell activation is much more complicated than outer hair cell activation. The movement of fluid within the scala media relies on the resonance (vibration) of both the tectorial membrane and the organ of Corti. Cells within the organ of Corti are much more flexible than cells within the basilar membrane. Alterations in the stiffness of these cells change the resonance of the organ of Corti and, subsequently, fluid movement within the scala media.[1] The outer hair cells alter the stiffness of the organ of Corti through a motor protein, prestin, located on the lateral membrane of these cells. These proteins vary in shape in response to voltage changes. Depolarization of the outer hair cells causes prestin to shorten, shifting the basilar membrane and increasing the membrane deflection, thereby intensifying the effect on the inner hair cells.[3][4][5][6]

Embryology

The inner ear originates from the invagination of the otic placodes during the fourth week of development. The otic placodes are sensory placodes, a series of transiently thickened surface ectodermal patches that form rostrocaudally pairs in the region of the developing head. Sensory placodes develop special sensory systems like vision, olfaction, and hearing. The otic placodes are 1 of the first sensory placodes to form and contribute to forming the inner ear structures associated with hearing and balance. Otic placode induction depends on Wnts and FGFs provided by the hindbrain and surrounding head mesenchyme. The otic placodes are located behind the second pharyngeal arch and give rise to the otic pits by invaginating into the mesenchyme adjacent to the rhombencephalon during the fourth week of development.

Near the end of the fourth week, the otic pits break off from the surface ectoderm to form a hollow piriform-shaped structure lined with columnar epithelium called the otic vesicle. The otic vesicle lies beneath the surface ectoderm enveloped in the mesenchyme, forming the otic capsule. The statoacoustic ganglion also forms during the formation of the otic vesicle and splits into cochlear and vestibular portions. The otic vesicle differentiates to form all the components of the membranous labyrinth and ultimately gives rise to the inner ear structures associated with hearing and balance. As the otic vesicle develops into the membranous labyrinth, its epithelium undergoes variations in thickness and begins to distort. The otic vesicle divides into a dorsal utricular portion and ventral saccular portion, with the dorsal utricular portion giving rise to the vestibular system and the ventral saccular portion giving rise to inner ear structures like the organ of Corti that are involved in hearing. The ventral saccular portion develops into the cochlear duct (which houses the organ of the Corti) and saccule. The dorsal utricular portion forms into the utricle, semicircular canals, and endolymphatic tube.

In the 6th week of development, the ventral saccular component of the otic vesicle penetrates the surrounding mesenchyme in a spiraling fashion. It completes 2 and a half turns to form the cochlear duct by the end of the 8th week. The saccule connects to the utricle via the ductus reuniens, and mesenchyme surrounds the entire cochlear duct. The mesenchyme surrounding the cochlear duct forms cartilage. During the tenth week of development, this cartilaginous shell undergoes vacuolization to create the 2 perilymphatic spaces of the cochlea, the scala vestibule, and the scala tympani. Two membranes separate the cochlear duct proper, also known as the scala media, from the scala tympani and scala vestibule. The basilar membrane demarcates the scala media from the scala tympani, while the vestibular membrane separates the scala media from the scala vestibule. Laterally, the cochlear duct is attached to the surrounding cartilage via a connective tissue structure called the spiral ligament.

The organ of Corti is located within the scala media of the cochlear duct and resides on the basilar membrane. The capsular cartilage surrounding the membranous labyrinth becomes ossified between 16 and 23 weeks gestation to form the true bony labyrinth. The organ of Corti is the sensory portion of the cochlear duct located between the scala media and scala tympani. There is 1 row of inner hair cells and 3 rows of outer hair cells surrounded by supporting cells. Inner and outer hair cells form, differentiate, and separate into their respective rows before forming the Deiters or supporting cells. Several genes share links with the embryological development of the organ of Corti. Cochlear duct growth and hair cell formation are linked to identified genes. Regarding neural development, the spiral ganglion, which innervates the organ of Corti, forms from the primitive otocyst preceding the organ’s development.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The labyrinthine artery is the main supplier of oxygenated blood to the cochlea and, therefore, to the organ of Corti. This artery is also known as the auditory artery or the internal auditory artery. The labyrinthine artery most commonly originates from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery most commonly originates from the basilar artery. About 15% of the time, the auditory or labyrinthine artery can occasionally branch off directly from the basilar artery. This artery may originate less commonly from the superior cerebellar or vertebral artery. The labyrinthine artery follows the vestibulocochlear nerve from its origin into the internal acoustic meatus, which divides into 2 branches: the anterior vestibular artery and the common cochlear artery. The common cochlear artery then divides into 2 more arteries: the proper cochlear artery and the vestibulocochlear artery. The vestibulocochlear artery then gives off the vestibular ramus and the cochlear ramus.[8][9]

Nerves

Inner hair cells are mechanoreceptor cells. They transmit information about acoustic stimuli directly to the type I spiral ganglion neurons (ie, auditory nerve, radial afferents). These afferents synapse within the cochlear nucleus within the brain. Input from the inner hair cells to the type I spiral ganglion neurons can be altered by lateral olivocochlear efferent nerves with axodendritic synapses onto these type I ganglion neurons. The lateral olivocochlear nerves do not synapse onto inner hair cells. They terminate on the auditory nerve fibers within the cochlea.[10][1][11] Outer hair cells have both efferent and afferent connections. They receive input from medial olivocochlear neurons directly onto their cell bodies, axosomatic synapses. These efferent connections form feedback loops that manipulate the stiffness of the organ of Corti and, therein, the activity of the inner hair cells. The outer hair cells synapse onto type II spiral ganglion neurons.[1][11] The function of these afferents is still unknown. These neurons do not respond to auditory stimuli.[1]

Physiologic Variants

Individual variations exist in the size and shape of the cochlea, which can have wide-ranging effects on surgical outcomes. Common variations include:

- The length of the outer cochlear wall

- The diameter of the cochlear tube (first turn of the cochlea)

- Length of the pars ascendens (first turn of the cochlea)

- The width of the scala tympani (the ascending portion of the cochlear duct)

Individuals with narrow scala tympani or small cochlear size are at potential risk of experiencing trauma during electrode implantation. Also, the variation in the diameter of the cochlear tube may result in limitations with conventional cochlear implants. Some of the smaller diameter tubes may not be large enough for the surgeries in some individuals.[12][13]

Surgical Considerations

Electrode array placement into the cochlea is a current treatment option for high-grade sensorineural hearing loss. Surgical complications are typically associated with surgical technique or device failure. Complications are classified as either minor or major. The most common minor complications include infections, vestibular problems, and persistent tinnitus. Major complications include more serious infections such as coalescent mastoiditis or meningitis, damage to middle or inner ear structures, and device failure problems.[14] These complications have dramatically decreased in recent years with small surgical incisions, the development of smaller implants, and more biocompatible implants.[15] During electrode array surgery, surgeons should be aware of the location of the petrous portion of the internal carotid artery and the jugular bulb. These structures lie near the tympanic cavity and should be avoided during surgery. Although not common, anatomical variations for both structures occur, including the absence of the bone dividing these vessels and the middle ear and the positioning of 1 or more vessels in a superior or lateral direction from normal. These structures can be damaged during surgery, or damage may occur due to post-surgical inflammation. To avoid these complications, CT or MRI imaging of the region should be performed before surgery to identify anatomical abnormalities. If imaging reveals anomalies, surgery within the tympanic cleft should be avoided.[16]

Clinical Significance

Sensorineural hearing loss is the most commonly reported cause of auditory deficits. This hearing loss often results from exposure to either loud sounds or ototoxic drugs. Exposure to loud noises causes the vibrational shift between the tectorial and basilar membranes to increase. This shift can damage the stereocilia of the outer hair cells. When damage occurs to the outer hair cells, the stiffness of the organ of Corti decreases, increasing vibrational forces on the inner hair cells. Damage to the outer hair cells decreases the protection of inner hair cells and causes them to become more sensitive. Over time, the inner hair cells also become damaged and audition affected.[1] Aminoglycoside antibiotics are an example of ototoxic drugs. These drugs are K+ channel blockers. As such, they block the ability of both inner and outer hair cells to depolarize. These drugs can also change the concentration of ions within the perilymph, leading to damage or death of both inner and outer hair cells; destruction of the hair cells causes permanent auditory deficits because they do not regenerate.[1]