Introduction

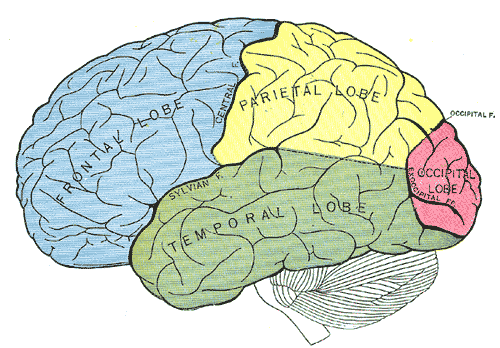

The occipital lobe is the smallest of the four lobes of the cerebral hemisphere. It is present posterior to the parietal and temporal lobes. Thus, it forms the caudal part of the brain. Relative to the skull, the lobe lies underneath the occipital bone. It rests on the tentorium cerebelli, which separates it from the cerebellum. The paired occipital lobes are separated from each other by a cerebral fissure. The posteriormost part of the occipital lobe is known as the occipital pole.

The occipital lobe is primarily responsible for visual processing. It contains the primary and association visual cortex.

Structure and Function

The demarcation of the occipital lobe from the parietal and temporal lobe on the medial surface by the parieto-occipital sulcus and on the lateral surface by an imaginary line that extends from parieto-occipital sulcus to the preoccipital notch.[1]

The cerebral surface of the occipital lobe irregularly molds into eminences called gyri and separated by depressions called sulci. The lateral surface of the occipital lobe consists of three characteristic occipital sulci: the intra-occipital sulcus, the transverse occipital sulcus, and the lateral occipital sulcus. The intra-occipital sulcus is an extension of the intraparietal sulcus of the parietal lobe. The transverse occipital sulcus crosses the superolateral surface of the brain transversely and lies posterior to the parieto-occipital sulcus. The lateral occipital sulcus is a horizontal sulcus that divides the lateral occipital surface into gyri. The occipital lobe commonly subdivides into superior and inferior gyri by the lateral occipital sulcus. Occasionally it divides into three occipital gyri; superior, middle, and inferior, by the lateral occipital sulcus and extension of the transverse occipital sulcus. The superior and inferior gyri converge to form the occipital pole.[2]

The medial surface of the occipital lobe has a characteristic calcarine sulcus (calcarine fissure). It extends from the parieto-occipital sulcus to the occipital pole. The upper and lower banks of calcarine sulcus house the primary visual cortex. Each primary visual cortex receives visual information from the contralateral half of the brain. The calcarine sulcus divides the medial surface into cuneus (superior gyrus) and lingual (inferior gyrus). The fusiform gyrus extends from the temporal lobe and lies below the lingual gyrus.

The occipital lobe is the visual processing area of the brain. It is associated with visuospatial processing, distance and depth perception, color determination, object and face recognition, and memory formation. The primary visual cortex, also known as V1 or Brodmann area 17, surrounds the calcarine sulcus on the occipital lobe's medial aspect. It receives the visual information from the retina via the thalamus. The secondary visual cortex, also known as V2, V3, V4, V5, or Brodmann areas 18 and 19, surrounds the primary cortex and receives information from it.

The primary visual cortex transmits information through two pathways: the dorsal and ventral stream. The dorsal stream is associated with object location and carries visual information to the parietal lobe. The ventral stream has associations with object recognition and transmits visual information to the temporal lobe.

Embryology

The occipital lobe of the cerebral cortex derives from the telencephalon. Thus, its embryologic development is associated with the development of telencephalon. At two weeks of conception, the embryo is a two-layered structure. During the third week, gastrulation divides the embryo into three layers – the endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. The ectodermal stem cells give rise to the brain and central nervous system.

The neuroectodermal cells become arranged in the midline forming the neural plate. At the end of the third developmental week, the neural plate ends approximate and fuse to form the neural tube. By week 4, the neural tube expands to form three characteristic cavities called the brain vesicles. This stage is known as three vesicle stage. The anterior-most cavity is prosencephalon, the middle cavity is mesencephalon, and the caudal cavity is rhombencephalon. By week 5, the prosencephalon further divides to form the “telencephalon” and “diencephalon,” and the rhombencephalon further divides to form the “metencephalon” and “myelencephalon.” This stage is known as five vesicle stage.[3]

The telencephalon undergoes growth and infoldings to form two cavities. The cavities give rise to cerebral hemispheres and the lateral ventricles. At five months, the hemispheres have expanded to occupy most of the brain cavity. At eight months, the gyri and sulci become prominent.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The occipital lobe receives vascular supply from the cortical branches of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA). The parieto-occipital artery originates from the distal segment of PCA in the calcarine sulcus. It supplies the parieto-occipital sulcus and some areas of cuneus. The calcarine artery also originates from the distal segment of PCA. It supplies the calcarine sulcus and most of the cuneus. The lingual gyrus artery arises near the origin of the calcarine artery.

As the name suggests, it supplies the lingual gyrus. The posterior-temporal artery supplies the lingual gyrus and caudal portion of the fusiform gyrus. The common temporal artery is also known as the lateral occipital artery or temporooccipital artery. It supplies the fusiform gyrus and sometimes lingual gyrus. Various neurologic deficits can occur as a result of occlusion of these branches, because of the variability of the regions supplied by the tributaries of the PCA.[5]

Surgical Considerations

Surgery of the occipital lobe is important for lesions such as gliomas and metastases. Neurosurgeons can approach these lesions through a trans-sulcal approach, or use sulci as an anatomical guide to perform en bloc resection. Sometimes surgeons access the occipital lobe to approach deeper structures of the brain. The detailed knowledge of its structure and anatomical map facilitates surgeries involving the area. Studies show that the location of the calcarine sulcus is invariably in the posterior interhemispheric fissure region. It has a minimal number of side branches and always arises from the parahippocampal gyrus. Thus, making it an important landmark for surgical approaches to the area. On the lateral surface, the transverse sulcus is most consistently present.[1][2]

Surgery has also proven successful in patients of medically-resistant occipital lobe epilepsy (OLE). However, it is challenging to identify the entire epileptogenic zone on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ictal electroencephalography (EEG). Additionally, resection of the lesion is often limited in an attempt to preserve the visual field, often leading to worse outcomes. Postoperative visual deficits are common with OLE surgery.[6]

Clinical Significance

Injury to the occipital lobe can occur due to vascular insults, neoplastic lesions, trauma, infections, and seizures. Depending on the type and location of the injury, specific neurological deficits can occur.

Unilateral occipital lobe lesion causes contralateral homonymous hemianopia. It is a visual field defect on the same side of both eyes contralateral to the site of the lesion — lesions of the occipital lobe due to the posterior cerebral artery infarct cause homonymous hemianopia with macular sparing. Macular sparing is due to the dual blood supply of the occipital pole by middle and posterior cerebral arteries. Lesions of the posterior occipital lobe may cause homonymous hemianopia with sparing of crescent-shaped temporal vision. The posterior lobe lesions spare the anterior striate cortex, which controls temporal vision. Bilateral occipital lesions cause bilateral complete hemianopia, also known as cortical blindness.

Anton syndrome is sometimes present in patients with cortical blindness. It occurs in cases of insult to the occipital lobe. The patient persistently denies loss of vision and is unaware of the visual deficit, despite evidence of cortical blindness. Confabulation often accompanies this deficit.[7][8]

Another rare syndrome associated with occipital lobe injury is Riddoch syndrome. The person is only able to see moving objects in the blind field, while non-moving objects are invisible. The person has motion perception while unable to perceive shape or color.[9]

Occipital lobe epilepsy is relatively uncommon but often presents with specific neurological findings. Seizures originating in the occipital lobe are associated with visual hallucinations, blurring or loss of vision, and rapid eye blinking or fluttering of eyelids. The seizures usually occur after a bright visual image or flicker stimulus.[10]

Occipital lobe lesions can cause visual hallucinations, color agnosia, or agraphia.