Continuing Education Activity

Niacin (vitamin B3) deficiency results in a condition known as pellagra. Pellagra includes the triad of dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea and can result in death. In addition, niacin deficiency can occur through genetic disorders, malabsorptive conditions, and interaction with certain medications. Today, niacin deficiencies are uncommon in industrialized nations primarily due to sufficient dietary intake; however, specific populations remain at risk of this mostly eradicated condition. Today, niacin deficiencies are uncommon in industrialized nations primarily due to sufficient dietary intake; however, specific populations remain at risk of this mostly eradicated condition. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of niacin deficiency and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the etiology of niacin deficiency.

Review the risk factors for developing niacin deficiency.

Explain the common physical exam findings associated with niacin deficiency.

Outline the importance of collaboration and communication among the interprofessional team to improve outcomes for patients with niacin deficiency.

Introduction

Niacin or vitamin B3 are generic terms for nicotinic acid and nicotinamide (niacinamide). Niacin was initially referred to as the anti-black tongue factor due to niacin's effect on dogs.[1] In humans, niacin was discovered through the niacin deficiency condition pellagra. In the 1700s, pellagra first appeared in Italy, and the name translates into "pella," meaning skin, and "agra," meaning rough.[2] In the early 1900s, pellagra was prevalent in the Southern United States due to the low availability of corn, the primary dietary source of niacin.[3] In 1937, Elvehjem and his colleagues isolated the vitamin and demonstrated that pure nicotinic acid and nicotinic acid amide would reverse the black tongue and pellagra.[4] Today, niacin deficiencies are uncommon in industrialized nations primarily due to sufficient dietary intake; however, specific populations remain at risk of this mostly eradicated condition.

Previously nutritional deficiency was the commonest cause of pellagra in the world. However, this is no longer true in developed countries, where it has been nearly eradicated as a manifestation of primary nutritional deficiency. Instead, it now presents a consequence of chronic alcoholism, malabsorption syndrome, adverse drug effects, and anorexia nervosa.[5]

Etiology

Niacin deficiency can occur from a lack of consuming dietary sources containing niacin.[6] In dietary sources, niacin is present in fish, meats, and fortified foods such as cereal, bread, and legumes. To a lesser extent, niacin is in coffee, tea, and nuts. During meat processing, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP) can become hydrolyzed to free nicotinamide. In some foods, such as corn, niacin can be covalently bound to carbohydrates or small peptides, decreasing the bioavailability for absorption in the small intestines. Therefore, some of the earliest signs of pellagra occurred in populations consuming a high corn-based diet. In addition to dietary sources, the liver can synthesize niacin from tryptophan; thus, a diet containing both niacin and tryptophan is necessary to maintain adequate niacin levels.[7]

Drugs, alcoholism, gastrointestinal tract diseases, and malignancies are the common causes of secondary pellagra.[8] Excessive and chronic alcohol intake can induce pellagra due to reducing the absorption of niacin. Alcohol use disorder is associated with increased malnutrition and can impair the conversion of tryptophan to niacin.[9] Niacin is primarily absorbed in the small intestine; therefore, malabsorptive disorders such as chronic diarrhea, inflammatory bowel disease, and malignancy can impair niacin absorption. Further, Hartnup disease results in impaired tryptophan absorption.[10] De Oliveira Alves et al. published a case report of a seropositive HIV patient with alcohol excess who had systemic features, progressive disorientation, and dermatological manifestations of pellagra. Management with nicotinamide led to rapid improvement after three weeks of treatment.[11]

Also, some medications, such as isoniazid, may cause an increase in the risk of niacin deficiency. Isoniazid binds with vitamin B6 and reduces PLP-dependent kynureninase activity, a required substance for niacin synthesis.[12][13] The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends prophylactic isoniazid for tuberculosis (TB) in patients receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) where the incidence of TB is high.[14] The risk of pellagra in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) patients with latent TB who received isoniazid prophylaxis has been studied.[15] Isoniazid decreases niacin levels by inhibiting its intestinal absorption and endogenous production from tryptophan. Essentially, the human body treats the structurally similar isoniazid as if it were niacin and behaves as if niacin concentrations are sufficient.

There have been reports of the development of pellagra in patients taking second-line anti-TB drugs, such as ethionamide.[16] Specific chemotherapeutic agents can also lead to niacin deficiency, such as fluorouracil and 6-mercaptopurine.[17]

In patients with carcinoid tumors, there is excessive serotonin production. Increased serotonin production utilizes more tryptophan resulting in the deficiency of substrate left for niacin synthesis.[18]

Epidemiology

Niacin deficiency results in the condition of pellagra, which, although uncommon in industrialized nations, may be seen in individuals living in poverty or those with extremely low niacin and protein-deficient diets.[19] Homeless individuals with malnutrition or patients with other comorbid conditions such as anorexia nervosa should be assumed to have a potential deficiency. Further, individuals with malabsorption, alcohol use disorder, or taking specific medication are at risk of deficiency.[2]

Corn was the staple food in China, India, Africa, and Latin America, yet pellagra was common in African nations.[20] For instance, in 1990, pellagra was prevalent in 6.3% of Mozambican refugees in Malawi.[21] Over nine months, 691 Malawians living in Kasese developed pellagra, which primarily was due to eating a niacin-deficient diet.[22] In Angola, about one-third of 723 women and 6% of 690 infants and children (6 months to 5 years) had pellagra.[23] On the other hand, 0.7% of 142 Tanzanian patients (aged 55 to 99 years) with skin diseases were diagnosed with pellagra.[24]

In the United States, pellagra is rare due to the enrichment of processed flour with B vitamins. In the past, native people in North, Central, and South America consumed maize treated with lime or wood ashes, which increased the bioavailability of niacin in maize.[20] In India, niacin was deficient among 13% of 34 adolescent girls 10 to 13 years but not in boys.[25] In Thailand, consuming a traditional meal provides about 13% of the recommended niacin intake. Traditional meals consisted of canned fish, stir-fried roselle, ivy gourd omelets, mung bean noodle soup, or canned fish curry with chili paste and pumpkin.[26] In Switzerland, compared with vegetarian (n=53) and vegan (n=53) adults, omnivores (n=100) had a low intake of niacin (P<0.05). Yet plasma vitamin levels showed that vegetarians were the only deficient group (mu=398 nmol/l).[27]

Within the United States and industrialized nations, pellagra is rarely seen with the enrichment of foods and an overall decrease in nutritional deficiency-related diseases.[28] Outside the United States, pellagra still occurs in African nations, India, and parts of China. Further, there were recent reports of pellagra in refugees.[29]

Pathophysiology

Niacin is important for the metabolism of macronutrients (carbohydrate, protein, and fat) due to its being part of the NAD and NADP coenzymes.[30][31] Niacin deficiency results in decreased NAD and NADP coenzymes commonly seen in cases of malnutrition in resource-limited countries. A significant amount of chemical energy is produced during the oxidation of glucose. NAD/NADH transfers electrons in a pathway that captures the energy by producing high-energy phosphate bonds. This adenosine triphosphate (ATP) provides the energy required for other reactions of intermediary metabolism, simultaneously regenerating NAD from the reduced NADH. A part of this cofactor is converted to NADP/NADPH, which plays several distinct roles.

Additionally, other mechanisms contribute to niacin deficiency. Altered metabolism of tryptophan presents in carcinoid syndrome, impaired absorption of tryptophan is seen in the autosomal recessive condition Hartnup disease, and prolonged use of certain medications may decrease the production of tryptophan (isoniazid) or inhibit the conversion of tryptophan to niacin (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or 5-fluorouracil).[32][33][34]

Histopathology

Dermatitis in pellagra characteristically demonstrates erythematous bullous changes secondary to mild acute inflammation, which leads to degeneration of the stratum corneum, followed by increased cellularity and fibroblasts, capillary dilation, and increased proliferation and thickening of the epidermis. Inflammatory cells include lymphoid cells and a few plasma cells. Hyperpigmentation is also seen.[35] In the gastrointestinal tract, inflammation can spread, causing chronic gastritis. Inflammation also leads to diarrhea. There are also reports of neuronal chromatolysis in motor neurons and edema in glial and ependymal cells.

History and Physical

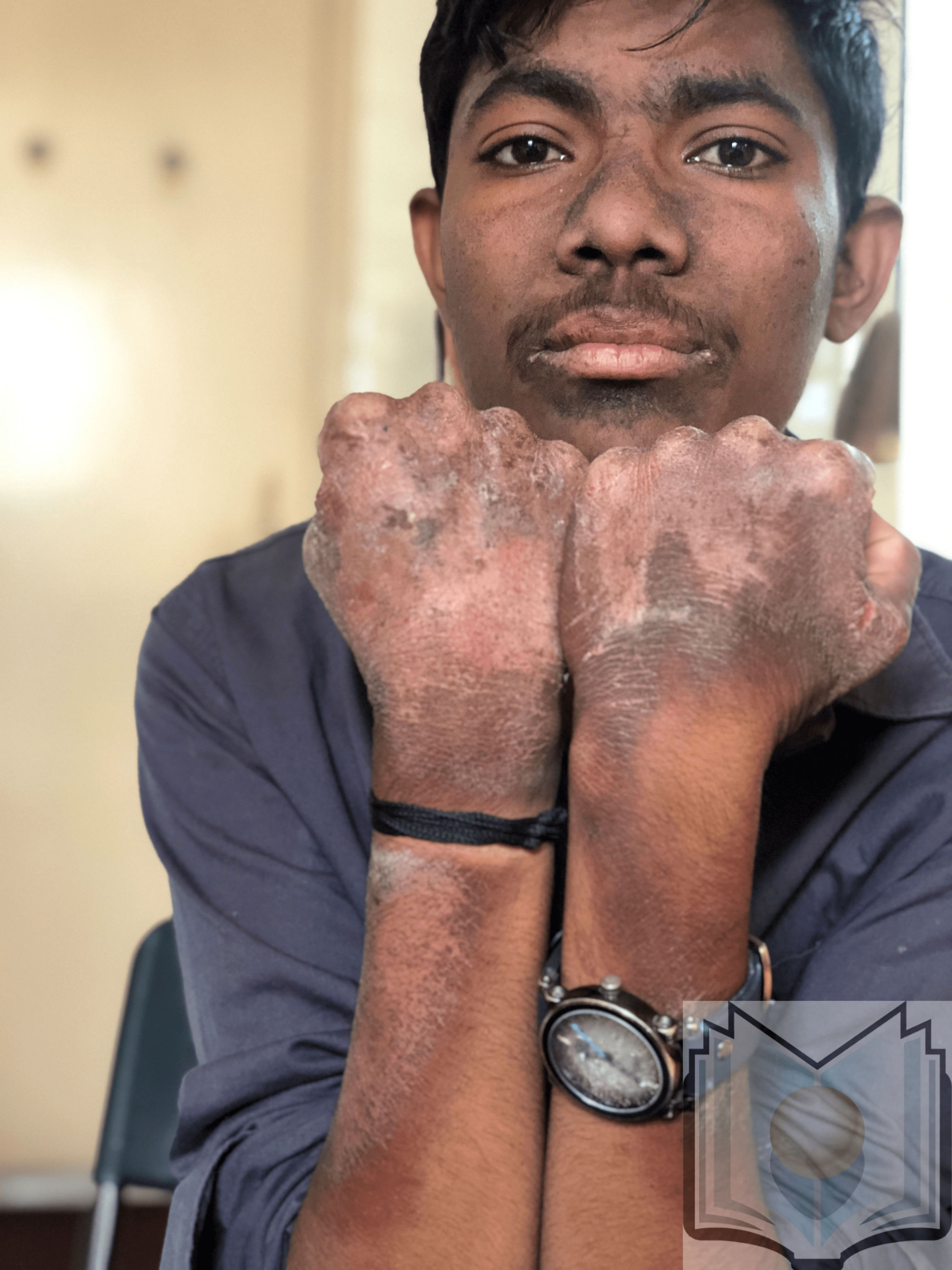

Pellagra is a condition caused by low levels of niacin or its precursor, tryptophan. Niacin deficiency results in pellagra, which includes the triad or "three Ds," dermatitis, dementia, and diarrhea, and can result in death. Similar to a sunburn, brown discoloration and skin lesions on the skin typically exposed to the sun, such as hands, elbows, knees, and feet, are present. Initially, neurological changes such as anxiety, poor concentration, fatigue, and depression can manifest, but dementia and delirium may occur as pellagra advances.[8] Also, gastrointestinal complications, glossitis, cheilosis, stomatitis, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea or constipation may be present.[6]

Symptoms of niacin deficiency can be divided into the following categories:

Gastrointestinal Findings

- Poor appetite, nausea, epigastric discomfort, increased salivation, and abdominal pain

- Gastritis and achlorhydria

- Glossitis, soreness of the mouth, and dysphagia

- The tongue becomes beefy red and appears raw due to atrophy of the papillae

- Diarrhea is typically watery but is occasionally bloody and mucoid

Skin Findings

- Erythematous skin with a burning sensation

- The distribution is typically symmetrical and bilateral sun-exposed areas of the body. In addition, there can be bullae named wet pellagra.

- Malar rash, dorsum of the hands and feet, and neck area common areas

- The skin findings of niacin deficiency, which responded to niacin treatment, have been described as an initial manifestation of Crohn disease[36]

Neuropsychiatric Findings

- Lethargy, apathy, depression, anxiety, poor concentration, and irritability

-

Disorientation, confusion, and delirium

-

Eventually, the patient may become stuporous and comatose

- Muscle weakness and paresthesias may be evident on clinical examination

Death

- Death occurs due to a deficiency of coenzymes necessary to generate adequate energy to support critical body functions

Evaluation

Laboratory testing should be completed to confirm the results and includes testing for tryptophan, NAD, NADP, and niacin levels.[8] Urinary excretion of N1-methylnicotinamide (NMN) of less than 5.8 micromols (0.8 mg/day) may suggest niacin deficiency. Erythrocyte nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) concentrations are also a sensitive indicator of niacin deficiency.

High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) of niacin metabolites in urine appears to be a sensitive investigation in identifying niacin deficiency.[37]

Therapeutic response to niacin administration in a patient with the typical features consistent with pellagra establishes the diagnosis.

Treatment / Management

The basic principle of treating niacin deficiency is the correction of underlying causes of niacin deficiency, but replacement of niacin is a must. For susceptible persons, preventive measures reduce the risk of developing the disease. One of these steps is supplementation.

A niacin deficiency may indicate multiple nutritional deficiencies; therefore, a balanced diet is a strong recommendation. Nicotinamide doses of 250 to 500 mg/day orally should be given. Despite nicotinic acid being the more common form of niacin, nicotinamide is used for niacin deficiencies as it does not cause symptoms such as tingling sensation, itching, or flushing.[8] Patients with pellagra should avoid sun exposure and alcohol intake. The recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for niacin is expressed as niacin equivalents (NE). The RDA for children ages 1 to 3 and 4 to 8 years of age is 6 and 8 mg/day of NE. For boys and girls ages 9 to 13, the RDA is 12 mg/day of NE. For individuals 14 years or older, the RDA is 16 and 14 mg/day of NE for males and females, respectively. RDA during lactation is 17 mg/day of NE.[38]

For patients who receive isoniazid for TB prophylaxis, B complex multivitamin or nicotinamide supplementation should be considered to prevent niacin deficiency.[39]

Treating patients with excess alcohol use who have multiple vitamin B deficiencies with a B complex with insufficient amounts of niacin or with pyridoxine and thiamine therapy without niacin could aggravate the neurological clinical state or trigger the appearance of alcoholic pellagra encephalopathy.

Differential Diagnosis

Pellagra is a condition that requires differentiation from generalized dermatitides, such as skin lesions due to sun exposure. Also, niacin deficiency should be distinguished from malnourishment, such as anorexia nervosa and kwashiorkor, or severe protein malnutrition typically characterized by an enlarged liver and edema seen during a famine.[8] Further, niacin deficiency can be overlooked with alcohol-induced pellagra and during alcohol withdrawal delirium.[9]

The following is the list of differentials one must consider when dealing with a patient with features indicative of niacin deficiency:

- Acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

- Crohn disease

- Discoid lupus erythematosus

- Drug eruptions

- Drug-induced lupus erythematosus

- Drug-induced photosensitivity

- Drug-induced pemphigus

- Porphyria cutanea tarda

- Ulcerative colitis

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Although there is no evidence of toxic levels for consuming niacin through foods, niacin consumption in heavily fortified foods, pharmacological or supplemental levels can result in adverse events. High levels of niacin (3000 mg/day) may cause flushing, jaundice, impaired vision, and abdominal discomfort, and a sustained high level can cause hepatotoxicity.[40] The tolerable upper intake level of 35 mg/day of niacin in adults 19 or older may cause adverse effects.[38]

Prognosis

If left untreated, pellagra will progress and eventually lead to death. Death can result as a complication of continued severe malnutrition due to a lack of dietary intake or continual diarrhea, infections, or neurological factors. Death may occur within 4 to 5 years of continued non-treatment.[8]

Pellagra was a significant widespread cause of death till the early 20 century; however, fortifying flour with niacin practically led to eradicating niacin deficiency in developed countries. However, many recent reports indicate that pellagra may even be underdiagnosed.[41]

Complications

Complications of niacin deficiency include the condition of pellagra (associated symptoms include mental confusion, glossitis, alopecia, dermatitis, sensitivity to sunlight, enlarged heart, peripheral neuritis, and dementia). The following is a concise list of complications that can occur secondary to niacin deficiency:

- Malnutrition and cachexia

- Secondary infection of the skin rashes

- Neuropsychiatric symptoms

- Coma

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

Niacin deficiency is preventable with an adequate diet rich in protein; therefore, nutritional education and food access are crucial to prevention. In individuals with malabsorptive conditions or those taking medications that reduce the availability of niacin, supplementation may be desirable.[8] In regions with a high risk of famine or a diet high in corn and low in protein (commonly seen in tribal populations), the fortification of food is essential.[22]

Adding milk, meats, peanuts, whole or enriched grains, green leafy vegetables, and brewers' dry yeast leads to better niacin intake. A semisolid or liquid diet may be needed for patients with oral dysphagia due to glossitis. Long-term inclusion of meat, milk, and eggs in the diet leads to dietary adequacy of proteins critical for recovery.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Pellagra is a condition of niacin deficiency, which is rare in industrialized nations. In individuals with malabsorption, lack of access to food, the use of certain medications, or alcoholism that may impair the absorption or synthesis of niacin, it may lead to a presentation of pellagra. After diagnosis and treatment, the prognosis of patients is excellent. Healthcare professionals working as an interprofessional team should use nutritional education to inform the patients and continue to monitor the patient throughout recovery. This interprofessional team, including clinicians (MDs, DOs, NPs, and PAs), nursing staff, pharmacists, and nutritionists/dieticians, can best guide patient treatment to an optimal recovery. All team members must maintain accurate records of all interventions and interactions with these patients and exercise open communication channels with other caregivers to ensure optimal patient outcomes. [Level 5]