Continuing Education Activity

The mediastinum is a cavity that separates the lungs from the other structures in the chest. Generally, the mediastinum is further divided into 3 main parts: anterior, posterior, and middle. Cancers in the mediastinum can develop from structures anatomically located inside the mediastinum or that transverse through the mediastinum during development and also from metastases or malignancies originating elsewhere in the body.

Definitive diagnosis of mediastinal cancer is typically made by mediastinoscopy with biopsy. This test is generally performed under general anesthesia and collects cells from the mediastinum to determine the type of mass present. The treatment for mediastinal cancers depends primarily on the type of cancer, its location, aggressiveness, and symptoms it may be causing. This activity for healthcare professionals aims to enhance learners' competence in selecting appropriate diagnostic tests, managing mediastinal cancers, and fostering effective interprofessional teamwork to improve outcomes.

Objectives:

Identify the etiology of mediastinal cancers.

Evaluate the various types of mediastinal cancers and tumor aggressiveness.

Differentiate between various types of mediastinal cancers through thorough diagnostic assessments.

Implement strategies to optimize care coordination among interprofessional team members to improve outcomes for patients affected by mediastinum cancer.

Introduction

The mediastinum is a cavity that separates the lungs from the other structures in the chest. Generally, mediastinum is divided into 3 main parts: anterior, posterior, and middle. The borders of the mediastinum include the thoracic inlet superiorly, the diaphragm inferiorly, the spine posteriorly, the sternum anteriorly, and the pleural spaces laterally. Structures contained within the mediastinal cavity include the heart, aorta, esophagus, thymus, and trachea.[1][2] The obtrusiveness of cancer and the severity of its signs and symptoms are dependent on its behavior within this visceral network. Cancers in the mediastinum can develop from structures anatomically located inside the mediastinum or that transverse through the mediastinum during development and also from metastases or malignancies originating elsewhere in the body.

Definitive diagnosis of mediastinal cancer is typically made by mediastinoscopy with biopsy. This test is generally done under general anesthesia and collects cells from the mediastinum to determine the type of mass present. The treatment for mediastinal cancers depends primarily on the type of cancer, its location, aggressiveness, and symptoms it may be causing.[3][4][5]

Etiology

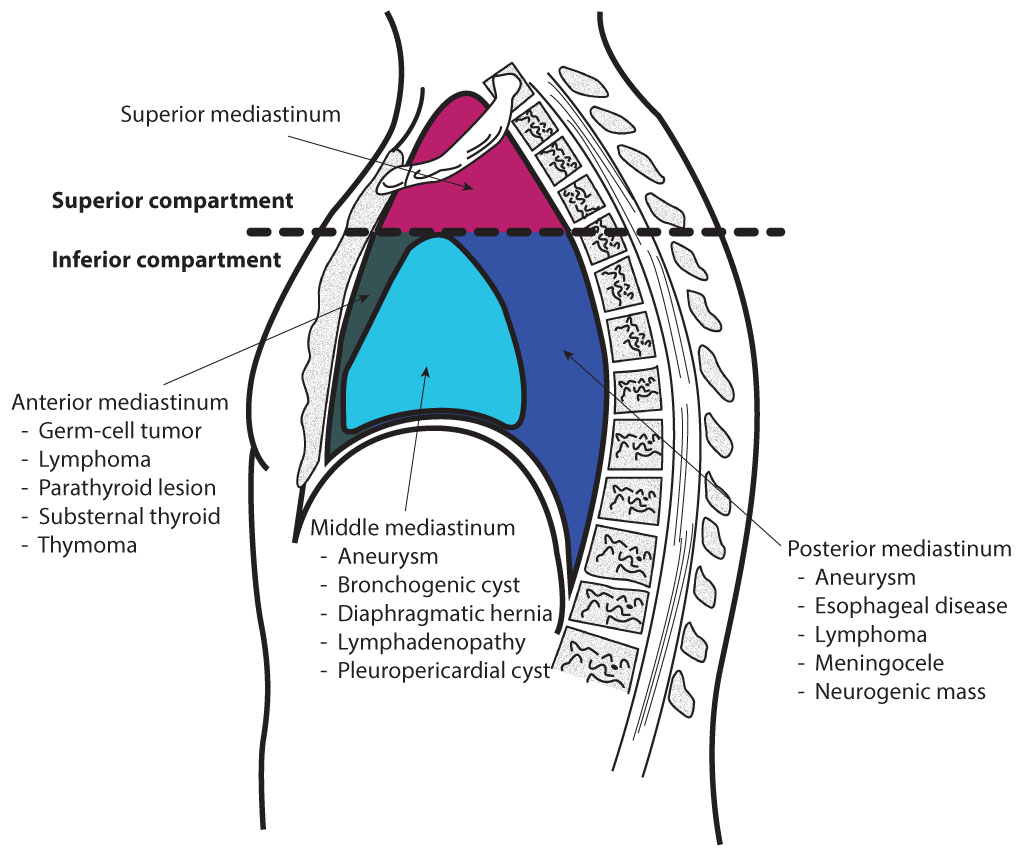

There are many different types of mediastinal cancers. The prognosis of each type depends on its behavior, proclivity to invade or disseminate, and resistance to treatment.[6] As stated above, the mediastinum can be proportioned into 3 parts: anterior, middle, and posterior, with each section having inherent neoplasms (see Image. Mediastinal Divisions).[7][8]

Anterior Mediastinum

The anterior mediastinum is bound by the pericardium posteriorly, pleural sacks laterally, and the sternum anteriorly.

Thymic carcinoma and thymoma

Thymic carcinomas are rare but highly aggressive, early-metastasizing cancers derived from thymic epithelial cells. They are also the most common cancers of the anterior mediastinum, comprising collectively with thymomas about 20% of all mediastinal cancers and 10% of all thymic tumors.[8] They can be further differentiated into squamous cell carcinoma, basaloid carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, lymphoepithelial-like carcinoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, clear-cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, nuclear protein of testis (NUT) carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma.[8] Like thymomas, thymic carcinomas occur in the 40 to 60 age range.[9] Thymic carcinomas have a fibrous stroma mixed with areas of necrosis, cystic changes, and calcifications. An initial diagnostic approach involves an evaluation by an MRI or CT, though the former is sometimes favored. These scans will delineate the extent of the disease, its invasiveness, and hence its potential for complete resection. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning has a less clear role as false-positive results occur in noncancerous entities such as fibrosing mediastinitis, thymic hyperplasia, and infections.[10] Thymomas, being well-differentiated, tend to be PET-negative, while thymic carcinomas are positive. Mediastinal thymic carcinoma is notably PET-positive; its presence portends a poorer prognosis.

Thymomas, like carcinomas, are also thought to originate from thymic epithelial cells.[9] The thymomas are thought to have a central role in the initial development of the immune system. The thymus typically regresses by puberty, but the immune foundation it serves is believed to be why thymomas are associated with many immune-based maladies. Examples include myasthenia gravis, red cell aplasia, polymyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Cushing syndrome, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone, acquired hypogammaglobulinemia (ie, Good Syndrome), and thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity which has a presentation akin to graft-versus-host disease. Thymomas oft occur in adults, rarely in youths or children. Although Asians and African Americans have a greater incidence, thymomas have no definitive risk factors. Thymomas behave in a slow-growing, indolent fashion but can become invasive. Thymomas may transform into carcinomas, which may take over a decade. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) advocates diagnosing thymomas using clinical and x-ray features and avoiding a biopsy when possible. This is due to the inherent danger of seeding the tumor within the biopsy tract. In aggregate, approximately 20% of thymic tumors require a pretreatment biopsy. A transpleural thymoma biopsy, in particular, should be avoided as it can seed a path within the pleural space, thereby converting what may have been a stage I thymoma into stage IV disease.

Germ cell tumor

The most common location for malignant germ cell tumors is the gonads; however, they can also arise in extragonadal regions. The mediastinum is the most commonly known location for extragonadal germ cell tumors. It has been speculated that they occur in these locations due to the abnormal migration of germ cells during embryogenesis. In adults, 10% to 15% of all mediastinal tumors are germ cell tumors, while an estimated 25% of tumors in children are germ cells. Approximately 30% to 40% of these germ cell tumors are malignant and mainly found in men. When a mediastinal germ cell tumor is discovered, primary testicular or ovarian germ cell tumors should be excluded because the mediastinum could be a site of metastasis. Germ cell tumors include seminomas, termed dysgerminomas in women, embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma, immature teratoma, and mature teratomas. Other germ cell tumors of the mediastinum include mixed germ cell tumors, germ cell tumors with somatic type solid malignancy, and germ cell tumors with associated hematological malignancy.[11]

Teratomas involve cells from the embryonal cell layers of the ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm.[12] They appear over the torso, including the mediastinum, when they fail to migrate properly during embryonal development.[13] They remain in the body midline but have a low incidence in the mediastinum, only 8% to 13%. Histologically, teratomas may be mature or immature (ie, having malignant elements).[14] Teratomas tend to occur in patients younger than 40 years. Benign mediastinal teratomas occur with equal frequency in males and females. Malignant teratomas are more common in males. Over half of the patients manifest no signs or symptoms.[12] When symptoms occur, the most common is dull, aching chest pain.[15] Characteristically, though not frequently, patients may manifest trichophytic or cough-up hair.[15] This is due to a fistula, communication between the teratoma and the tracheobronchial tree.

Other symptoms may include hemoptysis, fever, and pleural effusion.[13] The presence of a pleural or pericardial effusion is felt to overlay a tumor rupture.[16] Mediastinal (mature) teratomas contain soft tissue in almost all cases, fluid in 88%, fat in 76%, and not infrequently calcifications, ossifications, and teeth. The rapid growth of a teratoma has been ascribed to several mechanisms, including hemorrhage, ischemia or necrosis with concurrent inflammation, and damage caused by components of the tumor itself such as lipase and amylase (pancreatic), sweat (skin), and digestive juices (intestinal). Elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) or β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) levels exclude mature teratomas and seminomas and suggest a malignant diagnosis (eg, embryonal cancer, endodermal sinus cancer, or choriocarcinoma).[17] The elevated markers are diagnostic even if a biopsy is not. For benign mature teratomas, complete surgical resection is the only modality.[14][17] Adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation are not utilized. However, for immature teratomas, complete surgical resection with either adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy is felt to prolong survival. Treatment delays allow the mature teratoma to possibly convert to a malignant form. A delay in surgery can complicate the eventual effort to resect and cure. This tumor may become transfixed to surrounding structures, leaving the surgery fraught with risks like rupture, pulmonary atelectasis, infection, and empyema. While tumor size complicates resectability, surgical delay can bring a perioperative demise.

"Growing teratoma syndrome" (GTS) is a special situation that can occur anywhere within the torso but is particularly problematic within the mediastinum.[18][19][20] Recognizing GTS demands a shift in treatment. In germ cell tumors, the syndrome has a 1.9% to 7.6% prevalence. Typically, GTS occurs during the treatment of nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. These tumors would initially respond to platinol-based chemotherapy with shrinkage and normalization of their markers, AFP and β-hCG. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), if elevated, might also normalize. However, the tumor may suddenly grow faster during the treatment cycle, though the markers remain negative. What is believed to have happened is that the chemotherapy destroyed the immature malignant cells but allowed the growth of a mature, benign teratomatous component.

Unlike their germ cell cohort, AFP and β-hCG are undetectable in benign teratomas, and PET scan findings are negative. Benign teratomas are also resistant to both chemotherapy and radiation. With the discovery of GTS, the chemotherapy should be stopped, and the only modality of treatment, complete surgical resection, should be given. GTS has been reported in the retroperitoneum, the most common site, and the lung, forearm, mesentery, liver, pineal gland, and the inguinal, cervical, and supraclavicular nodes. The benign teratomatous element proliferates, and if surgery is delayed, these elements can overrun and obstruct the surrounding viscera. In this situation, excluding other nonmalignant sources of tumor markers is essential, such as an elevated AFP due to hepatic dysfunction or elevated β-hCG due to marijuana use. Generally, with surgery, the overall survival can be 90%; incomplete resection brings recurrence. Histologic analysis of the resected specimen shows a benign mature teratoma with a non-germ cell component. In the mediastinum, the treatment data appears relatively poorer. The 5-year overall survival rate is 30% to 45%, with a 4% operative mortality due primarily to pulmonary problems. Following complete resection, GTS can recur in up to 4% of cases; with incomplete resection, the rate can be as high as 83%.

Lymphoma

Primary mediastinal lymphoma is a relatively uncommon tumor, generally observed in senior women and men. The most common types of primary lymphomas that present as a disease in the mediastinum are primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, Nodular Sclerosing Hodgkin's disease, marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), as well as the more rare T-lymphoblastic leukemia or lymphoma, anaplastic large cell lymphoma, and other T-, B-, and NK-cell entities. Secondary lymphomas of the mediastinum, which originate elsewhere in the body and metastasize to the mediastinum, are more common than primary mediastinal lymphomas.[21] Primary mediastinal lymphoma is a tumor of large B cells with concurrent sclerosis, likely of thymic B cell origin.[22] Primary mediastinal lymphoma is an entity separate from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Microscopic analysis may resemble this lymphoma or nodular sclerosing Hodgkin disease, found in young adults and virtually confined to the anterior mediastinum. Treatment initially involves complex chemotherapy with radiation reserved for consolidation.[23] For relapse, intensive chemotherapy followed by an autologous stem cell transplant is the favored approach. Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin disease frequently presents as an anterior mediastinal mass, though rarely obstructive or obtrusive.[24]

Cervical or supraclavicular adenopathy may be present, though identification is often incidental. Chemotherapy carries a 90%, or more, 5-year survival. PET scanning is used in initial staging and to judge the efficacy of therapy. Patients with good responses seen on the PET scan can negate a full course of chemotherapy or the addition of radiation.[25][26] Marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (ie, MALT or thymic MALT lymphoma) is a relatively rare lesion of the anterior mediastinum.[27] These tumors are often found in Asian adult females and are associated with autoimmune diseases, especially Sjogren syndrome.[28] The behavior of MALT is indolent and frequently exists as an encapsulated tumor, often with cystic regions and rarely with adenopathy. The literature advocates an en-bloc surgical resection of the nodes and tumor with adjuvant chemotherapy (eg, RCHOP) for positive nodal disease.

Middle Mediastinum

The middle mediastinum is bounded by the pericardial and bilateral pleural sacks both anteriorly and posteriorly.

Parathyroid adenoma

Several tumors can metastasize to the middle mediastinum. Parathyroid adenoma is one. Primary hyperparathyroidism affects up to 0.5% of the population, with increasing incidence after 50 years of age.[29] While a quarter of the cases have ectopic foci, only about 2% are in the mediastinum, less so in the middle portion. Surgical resection is the treatment of choice, offering cures to upwards of 98%.[30] Treatment failure is due to either an incomplete resection or ectopic foci, as in the middle mediastinum. Because of this difficulty, experts recommend that patients undergo a preoperative evaluation with concurrent Tc99-Sestamibi and single-photon emission (SPECT/CT) scanning that carries an excellent sensitivity for defining ectopic disease.[31] Better preoperative planning is essential as middle mediastinal lesions favor a sternotomy approach, different from others.[32]

Posterior Mediastinum

The posterior mediastinum is bounded by the pericardium anteriorly, the diaphragm inferiorly, and the transverse thoracic plane superiorly.

Neurogenic mediastinal neoplasms

These neurogenic tumors represent >60% of the masses found in the posterior mediastinum, are primarily found in children, and can reach a large size before becoming symptomatic. Approximately 30% of neurogenic neoplasms are malignant. They present with a large variety of clinical and pathological features that are classified by the origin of the cell type. These are the most common cause of neurogenic mediastinal cancers and are classified as nerve sheath neoplasms (eg, Schwannomas and neurofibromas) and ganglion cell neoplasms (eg, neuroblastomas and ganglioneuroblastomas).

Schwannomas are nerve sheath tumors. Though only 9% of all Schwannomas occupy the mediastinum, they compose half of the mediastinal neurogenic tumors.[33][34][35] They are mostly benign and slow-growing, although malignant transformation can occur, typically in patients with neurofibromatosis. The treatment of benign tumors involves surgical resection, often using video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS). For malignant lesions, surgery is followed by adjuvant radiation. Chemotherapy is of no use. Neurofibromatosis lesions of the mediastinum that occur in conjunction with the vagus nerve are almost always found with von Recklinghausen disease.[36] Histologically, these are typical of a plexiform pattern, which makes surgical excision, the treatment of choice, more difficult. Neuroblastomas can arise from the sympathetic ganglia near the thoracic spine and are the most common tumor in children, with most patients <2 years of age.[37][38] Treatment requires surgical resection with adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Ganglioneuroblastoma is a tumor of the adrenal gland or the sympathetic nervous system and is most common in young children, particularly 1 to 2 years of age.[39][40] Early diagnosis and surgery are recommended as a 2-year survival of 92% is quoted in the literature. Recurrences tend to occur in adults and youths; the older the patient, the poorer the outcome.

Epidemiology

Mediastinal cancers are usually rare. Typically, they are diagnosed in patients aged 30 to 50 but can develop at any age from any tissue located or passing through the mediastinum. Children usually present with cancers in the posterior mediastinum, while adults typically present with cancers in the anterior mediastinum. There is a similar incidence in men and women, but it can vary with the type of cancer present.[41]

Histopathology

Various mediastinal cancers exist, and the histopathology depends upon tumor origin.

History and Physical

A detailed history and physical should be performed. The history and physical examination findings usually vary by the type of mediastinal cancer, its location, and the tumor's aggressiveness. Some people present with no symptoms, and cancers are typically found during imaging of the chest, which is performed for other reasons. If symptoms are present, they are often a result of cancer compressing the surrounding structures or symptoms from a paraneoplastic syndrome. These symptoms may include a cough, shortness of breath, chest pain, fever, chills, night sweats, hoarseness, unexplained weight loss, lymphadenopathy, coughing up blood, wheezing, or stridor. Mediastinal masses could also be associated with abnormalities in other body parts (eg, testicular masses with germ cell tumors). Thus, a thorough history is necessary, including a complete review of symptoms and a comprehensive physical examination. In general, malignant lesions tend to be symptomatic.

Evaluation

Cancers in the mediastinum have a wide diversity of presentations.[42][43] The location of cancer and its composition is paramount to narrowing the differential diagnosis. The medical adage "least aggressive to most invasive" applies well here. Depending on the situation, a biopsy can be precarious. For certain disorders, a biopsy may not be appropriate. The tests performed most commonly to diagnose and evaluate mediastinal cancers include:

Chest X-ray

Chest radiographs (posteroanterior and lateral) are usually the initial step in identifying a mediastinal mass. A chest x-ray can also help localize the anterior, posterior, or medial mediastinum mass to help with the differentials. The mass could be an incidental finding on an asymptomatic patient who has had a chest x-ray before elective surgery or an evaluation of an unrelated condition. It can also be done as an evaluation in patients who present with symptoms due to the mediastinal mass or paraneoplastic syndromes. In general, malignant lesions tend to be symptomatic. When a mass protrudes into the mediastinum, the normal structures (eg, aorta) lose their roentgenographic signatures, their "silhouette sign."[10] However, radiography is of minimal value in characterizing mediastinal cancers.

Chest Computed Tomography

To evaluate masses seen on chest x-rays, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest is usually performed with intravenous (IV) contrast, which can often show its exact location, whether the mass is well-circumscribed, or if it infiltrates the surrounding structures. In many cases, no further workup is necessary for diagnosis. Characterization of the mass on the CT scan is based on specific attenuation of water, air, fat, calcium, soft tissue, and vascular structures. High-resolution multiplanar reformation images demonstrate the detailed anatomical relationship of cancer's precise location, morphology, and relationship to the adjacent structures.

Chest Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated when CT findings are equivocal. Recently, special applications of MRI have been developed to identify precisely the tissue components of mediastinal masses. Excellent soft-tissue contrast makes MRI an ideal tool to evaluate cancers of the mediastinum. Chemical-shift MRI has helped differentiate normal thymus and thymic hyperplasia from thymic cancers and lymphoma. Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI) is another special application that unveils minute biophysical and metabolic differences between tissues and structures. The mean apparent diffusion coefficient for malignant mediastinal entities could be substantially lower than for benign diseases.

Mediastinoscopy with Biopsy

Definitive diagnosis of mediastinal cancer is typically made by mediastinoscopy with biopsy. This test, generally done under general anesthesia, collects cells from the mediastinum to determine the type of mass present. A small incision is made under the sternum, and a small tissue sample is removed to analyze if cancer is present. This test will help the clinician determine the type of cancer present with very high sensitivity and specificity. Establishing the diagnosis of lymphoma generally requires a core biopsy for flow cytometry.

Endobronchial ultrasound and Endoscopic ultrasound

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) has become the diagnostic procedure of choice for most mediastinal pathologies. Most of the mediastinal lymph node stations, including stations 2, 4, 7, 10, and 11, can be accessed with the help of an EBUS and combined with endoscopic ultrasound (EUS); even other stations like 7, 8, and 9 can be accessed. EBUS can be done under conscious sedation or general anesthesia and is usually a single-day outpatient procedure with minimal complications. EBUS is safer than mediastinoscopy, with almost similar diagnostic efficacy.

Laboratory Studies

Basic laboratory tests such as complete blood count (CBC) and basic metabolic panel (BMP) can help in the differential diagnosis of lymphomas. In the instances of mediastinal masses, tumor markers can help support a presumptive diagnosis, including:

- β-hCG, associated with germ cell tumors and seminoma

- LDH, which may be elevated in patients with lymphoma

- AFP associated with malignant germ cell tumor

Mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors are more likely to result in distinct elevations of serum AFP and less likely in elevations of β-hCG compared to gonadal or retroperitoneal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Malignant germ cell tumors are closely related to serum tumor markers, especially AFP and β-hCG. Measuring these serum tumor markers is essential in these patients' diagnosis, management, and follow-up.

Testicular Ultrasound

In suspected cases of metastasis to the mediastinum from primary testicular germ cell tumors, palpation of the testicles is insufficient, and ultrasonography of the testicles should be performed in all patients.

Treatment / Management

The treatment for mediastinal cancers depends primarily on the type of cancer, its location, aggressiveness, and symptoms it may be causing. The following are the treatments utilized for the most common mediastinal cancers.[3][4][5]

Thymic Cancers

Treatment of thymic cancers usually requires surgery, followed by radiation or chemotherapy. Pulmonary function studies and a cardiac evaluation should be done in any patient undergoing surgery on the thymus. This determines if the patient has enough cardiopulmonary reserve for the surgery.[9] Surgery is the initial treatment in patients who present with tumors invading readily resectable structures like the mediastinal pleura, pericardium, or adjacent lung. A resected specimen will then be sent for histopathologic examination for staging and to determine if postoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy is required. The ability to completely resect the thymic carcinoma depends on the degree of invasion and adherence to surrounding structures. The pericardium and surrounding lung parenchyma are sometimes removed to achieve complete resection with histologically negative margins.

Types of surgery that are being performed include minimally invasive thoracoscopy, mediastinoscopy, and thoracotomy. In patients for whom complete resection is not feasible as the initial treatment, for example, those with cancer invasion into the innominate vein, phrenic nerve, heart, or great vessels, therapy involving preoperative chemotherapy and postoperative radiotherapy is indicated. If neoadjuvant chemotherapy allows for a partial or complete response, these cancers are considered potentially resectable, and patients should be reevaluated following therapy. If complete resection cannot be accomplished with surgery, these patients should undergo maximum debulking followed by radiotherapy postoperatively if technically feasible. This may control the residual disease.

For unresectable cancers, systemic therapy, radiotherapy, or chemoradiotherapy may be recommended in patients with extensive pleural/pericardial metastases, nonreconstructable great vessel invasion, heart, tracheal involvement, or distant metastases. Although no clinical trials provide evidence of the benefit of surveillance after treatment, monitoring with thoracic imaging is warranted, given early intervention may be more effective.[44] As of the date of this writing, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) generally recommends a surveillance chest CT with contrast every 6 months for 2 years, then annually for 5 years in thymic cancer or 10 years for thymomas. Thymomas and thymic cancers having extrathoracic metastases are treated using chemotherapy. Locally advanced, the unresectable disease is treated with chemoradiation. Recurrences are approached based on resectability. Surgically operable lesions receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy and possible adjuvant radiation. As always, with neoadjuvant therapy, the purpose is to reduce the lesion and improve resectability. Unresectable recurrences receive radiation and possibly chemotherapy.

Teratoma

For benign teratomas, complete surgical resection brings a cure. Incomplete resection leads to local recurrence.[19] Immature teratoma or admixtures with other cancers necessitates neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy as the circumstance dictates.[16] As stated, an elevated marker, such as AFP or β-hCG, denotes a malignancy even if the biopsy fails to confirm it.

Lymphomas

Treatment depends on the type of lymphoma, its stage, and metastases. Most lymphomas are generally treated with chemotherapy followed by radiation.[45]

- Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma originates in the mediastinum and is managed like the early stage of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The primary treatment is around 6 courses of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP), and rituximab (R-CHOP). This could be followed by radiation to the mediastinum in suitable patients. A PET/CT scan is usually done after the chemotherapy to see if there are any lymphoma remnants in the chest. If no active lymphoma is observed on the PET/CT scan, the patient may be observed without further intervention. However, radiation may be necessary if the PET/CT scan shows a possible active lymphoma in the mediastinum. Often, a biopsy of the chest tumor is ordered by the clinician to affirm that the lymphoma is still present before starting radiation.

- Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma) is a rare cancer. MALT lymphoma can be treated with radiation therapy to the stomach, rituximab, chemotherapy, chemotherapy plus rituximab, or the targeted drug ibrutinib. Chlorambucil or fludarabine could be used for single-agent chemotherapy, or combinations such as CHOP or cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone (CVP) could be used. Hodgkin lymphoma treatment usually starts with chemotherapy.

- Nodular sclerosing Hodgkin's disease utilizes the most common 4-drug combination in the US: adriamycin (doxorubicin), bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine (DITC), which is given in cycles. Radiation therapy is often given after chemotherapy.

Neurogenic Tumors

Surgery is the preferred treatment for malignant neurogenic tumors. Procedures include a post-lateral thoracotomy, which can give the surgeon good exposure to the tumor, and, more recently, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS). VATS is a minimally invasive procedure that inserts a thoracoscope and surgical instruments through small incisions in the chest. This procedure decreases the access trauma and gives a good view, especially for smaller posterior mediastinal neurogenic tumors. Still, it is not ideal for giant mediastinal neurogenic tumors because of their huge volume. For dumbbell neurogenic tumors, sufficient preoperative evaluation is required of the intraspinal part of the tumor to prevent uncontrollable hemorrhage during surgery. The cooperation of a thoracic surgeon with a neurosurgeon is recommended for this procedure. For malignant mediastinal neurogenic tumors, the 5-year survival rate is low, and complete resection is rarely possible. There is frequent use of radiation in conjunction with chemotherapy before surgery to decrease the size of the tumor or after to treat the margin of the resection bed.

Mediastinal Germ Cell Tumors

Management of mediastinal germ cell tumors varies with the type of tumor present. It may include chemotherapy, surgery, radiotherapy, or a combination of these treatments.

- Mediastinal seminoma or dysgerminoma: Treatment essentially depends on the tumor size. For smaller sizes, patients usually undergo radiotherapy, which can eradicate the tumor. For larger tumors, the treatment of choice is chemotherapy. This commonly combines bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP). Radiation has a higher rate of recurrence compared to chemotherapy. If these treatments fail to eliminate all the tumor mass and the remaining area is smaller than 3 cm, patients are likely to be monitored periodically by the clinician to see if the tumor grows again. If the residual tumor is greater than 3 cm after treatment, the clinician can opt for routine monitoring or further surgery to remove the tumor.

- Mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors: Chemotherapy is the first-line treatment for primary mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. A combination of drugs is traditionally used, the most common being bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP), and standard therapy consists of 4 courses of BEP. Men with nonseminomatous primary mediastinal germ cell tumors have a worse prognosis of survival compared to men with mediastinal seminoma. After chemotherapy, patients may undergo salvage surgery to remove the remaining tumor. The optimal strategy for long-term survival in patients who present with mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors remains to be defined. A study at Indiana University described 31 patients with mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors who received cisplatin, bleomycin, and either vinblastine (20 patients) or etoposide (11 patients) followed by surgical resection; 15 patients (48%) achieved long-term disease-free survival. A retrospective study of 64 patients with mediastinal nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCTs), treated in France from 1983 through 1990, estimated a 2-year overall survival rate of 53%. More recently, a 5-year overall survival rate of 45% was reported in an international analysis of 141 patients with mediastinal NSGCT from 11 cancer centers, treated from 1975 through 1996 in the United States and Europe. Treatment variables that may determine survival outcomes include the patient's chemotherapy duration, the use of additional anticancer drugs such as anthracyclines and alkylating agents, and when the surgery was performed.

Differential Diagnosis

Retrosternal and intrathoracic goiters: Primary intrathoracic goiters behave differently from the more common secondary subtype.[46][47] The secondary form is an extension of the thyroid into the retrosternal space. The primary form is separate from the cervical thyroid, with their blood supply coming from intrathoracic sources. It may compress the trachea, which, if prolonged, can lead to a postoperative tracheomalacia that could require a tracheostomy. The treatment of choice is surgical resection.

Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis can exist as a unique entity called "mediastinal tuberculous lymphadenitis."[48] Tuberculosis is found almost always in children and Asian and African developing nations. The fundamental problem is not in the lungs so much as the inflammatory granulomatous disease in the hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. These nodes can enlarge and erode into the surrounding viscera. They may mimic other disorders, especially in the posterior mediastinum. They can cause fibrosing mediastinitis, constrictive pericarditis, and tubercular neuritis.

Aneurysm: Vascular anomalies can distort the overview, giving the radiologic appearance of an underlying mass.[49] In type IV Ehler-Danlos syndrome, there is a dysmorphism in the vascular wall predisposing to aneurysms, dissection, rupture, or fistulae. For symptomatic cases, surgical resection is advocated.

Bronchogenic cysts: These occur primarily in the middle mediastinum and secondarily to the abnormal budding of the tracheobronchial tree during fetal development.[50][51][52] Most cases are asymptomatic or may have a cough at most. Symptomatic patients are resected. Asymptomatic adults may have a conservative "watch-and-wait" approach. However, some advocate resection in young asymptomatic people to avoid late problems such as infection, hemorrhage, and neoplastic transformation.

Pleuropericardial cysts: These are congenital anomalies with a propensity for development in the middle mediastinum.[53][54][55] Some cysts may be acquired after cardiothoracic surgery. Most cysts are asymptomatic and are not prone to malignant transformation. Because aspiration can lead to infection, experts do not recommend the procedure. Most cases resolve spontaneously, but if symptoms do occur, like chest pain or dyspnea, surgery is to be performed. Pleuropericardial cysts can run the risk of hemorrhage, atrial fibrillation, and cardiac tamponade. Asymptomatic patients can be treated conservatively with close follow-up.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the cause and treatment response.

Complications

Respiratory compromise: Mediastinal masses can cause airway obstruction, leading to respiratory distress, also known as critical mediastinal mass syndrome.[56][57][58][59] When biopsy or surgery requires general anesthesia, these patients are at risk for tracheobronchial airway collapse. Muscle relaxants, sedatives, and paralytic agents are said to be avoided. Countermeasures include using extrinsic positive end-expiratory pressure as a "pneumatic splint" to maintain airway patency. Some have advocated cardiopulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Tracheomalacia: This is a condition where the trachea manifests excessive expiratory collapse due to damaged tracheal wall elastic fibers.[60][61][62] During expiration, the trachea narrows and shortens, but with wall damage, there is wall collapse and airway obstruction. It can occur due to chronic external tracheal compression from cancers. Still, tracheomalacia is also seen with nonmalignant causes, including cysts, abscesses, aortic aneurysms, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and polychondritis. Diagnosis is made by bronchoscopy. Conservative initial management with interventions (eg, continuous positive airway pressure) should be attempted. As circumstances dictate, surgical intervention could involve tracheobronchoplasty, tracheostomy, or stenting.

Consultations

Consultation with a thoracic surgeon and oncologist is essential for adequately managing mediastinal cancers.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to consider regarding mediastinal cancer include the following:

- Cancers in the mediastinum can develop from structures anatomically located inside the mediastinum or that transverse through the mediastinum during development and also from metastases or malignancies originating elsewhere in the body.

- Mediastinal cancers are usually rare. Typically, they are diagnosed in patients aged 30 to 50 but can develop at any age from any tissue located or passing through the mediastinum.

- Children usually present with cancers in the posterior mediastinum, while adults typically present with cancers in the anterior mediastinum.

- There is a similar incidence of mediastinal cancers in men and women, but it can vary with the type of cancer present.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Many lesions can occur in the mediastinum, and diagnosis can be challenging. An interprofessional approach including a primary care clinician, oncologist, radiologist, thoracic surgeon, anesthesiologist, and intensivist is recommended. Placing these individuals under general anesthesia also can cause respiratory obstruction and cardiovascular collapse because of the mass effect on the trachea. Anyone caring for patients with a mediastinal mass should follow the diagnosis, treatment, and posttreatment care recommendations.

Specialty-trained nurses should educate patients and families on the lesions and their posttreatment care. Some lesions, like lymphoma, may be treated with radiation, whereas most other lesions require surgery and chemotherapy. In the postoperative period, these patients need pain control, incentive spirometry, and ambulation to prevent early complications. The peri-anesthesia, critical care, and medical-surgical nurses should monitor the patient and inform the team about major changes or issues. Pharmacists should evaluate medication choices and drug interactions and educate the patients when appropriate.[63][64]

Outcomes

The outcomes for most localized lesions of the mediastinum in children and adults are good. However, if the lesions are large and invade local tissues, surgery may require the removal of important tissues like the phrenic nerve and innominate vein. Only via an intradisciplinary approach and communication with the different specialists can the morbidity of surgery and treatment be decreased.[65][66][67]