Continuing Education Activity

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing various liver disorders. With advancements in techniques, this procedure has become a safe and valuable tool for hepatologists managing a wide range of liver pathologies. A liver biopsy is indicated for diagnosing various hepatic conditions as well as serving as a prognostic tool, particularly in diseases like nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hemochromatosis, where the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis carries significant prognostic implications.

Several liver biopsy methods, including percutaneous, transvenous, laparoscopic, and plugged biopsy techniques, can be utilized. Each method has specific indications based on patient factors (eg, the risk of bleeding or the need for a targeted biopsy). Despite the availability of noninvasive markers, liver biopsy remains an essential diagnostic tool due to its ability to provide detailed histological evaluation, which is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management. This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learner's competence in performing liver biopsies, identifying indications, and implementing an appropriate interprofessional management approach to improve patient outcomes.

Objectives:

Implement appropriate techniques for a liver biopsy.

Evaluate the indications for a liver biopsy.

Assess the complications of a liver biopsy.

Apply interprofessional team strategies to improve care coordination and outcomes for patients undergoing a liver biopsy.

Introduction

Liver biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing various liver disorders. Though the first needle biopsy of the liver was reported to have been performed by Paul Ehrlich in 1883, with advancements in techniques, this procedure has become a safe and valuable tool for hepatologists managing a wide range of liver pathologies.[1][2][3] A liver biopsy is indicated for diagnosing conditions such as chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, storage diseases, unexplained hepatomegaly, and drug-induced liver injury. It also serves as a prognostic tool, particularly in diseases like nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hemochromatosis, where the presence of fibrosis or cirrhosis carries significant prognostic implications. Furthermore, liver biopsy is crucial in guiding treatment, especially in autoimmune hepatitis, where it helps monitor disease activity and treatment compliance.

Several liver biopsy methods, including percutaneous, transvenous, laparoscopic, and plugged biopsy techniques, can be utilized. Each method has specific indications based on patient factors (eg, the risk of bleeding or the need for a targeted biopsy). Despite the availability of noninvasive markers, liver biopsy remains an essential diagnostic tool due to its ability to provide detailed histological evaluation, which is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Indications

Liver biopsy has many indications, including histologic identification of the underlying etiology of various hepatic conditions, including chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, storage diseases, unexplained hepatomegaly or enzyme elevations, post-liver transplant liver-enzyme abnormalities, space-occupying lesions, intrahepatic cholestasis, drug-induced liver injury.[4][5][6] Indications for liver biopsy fall into the following 3 broad categories:

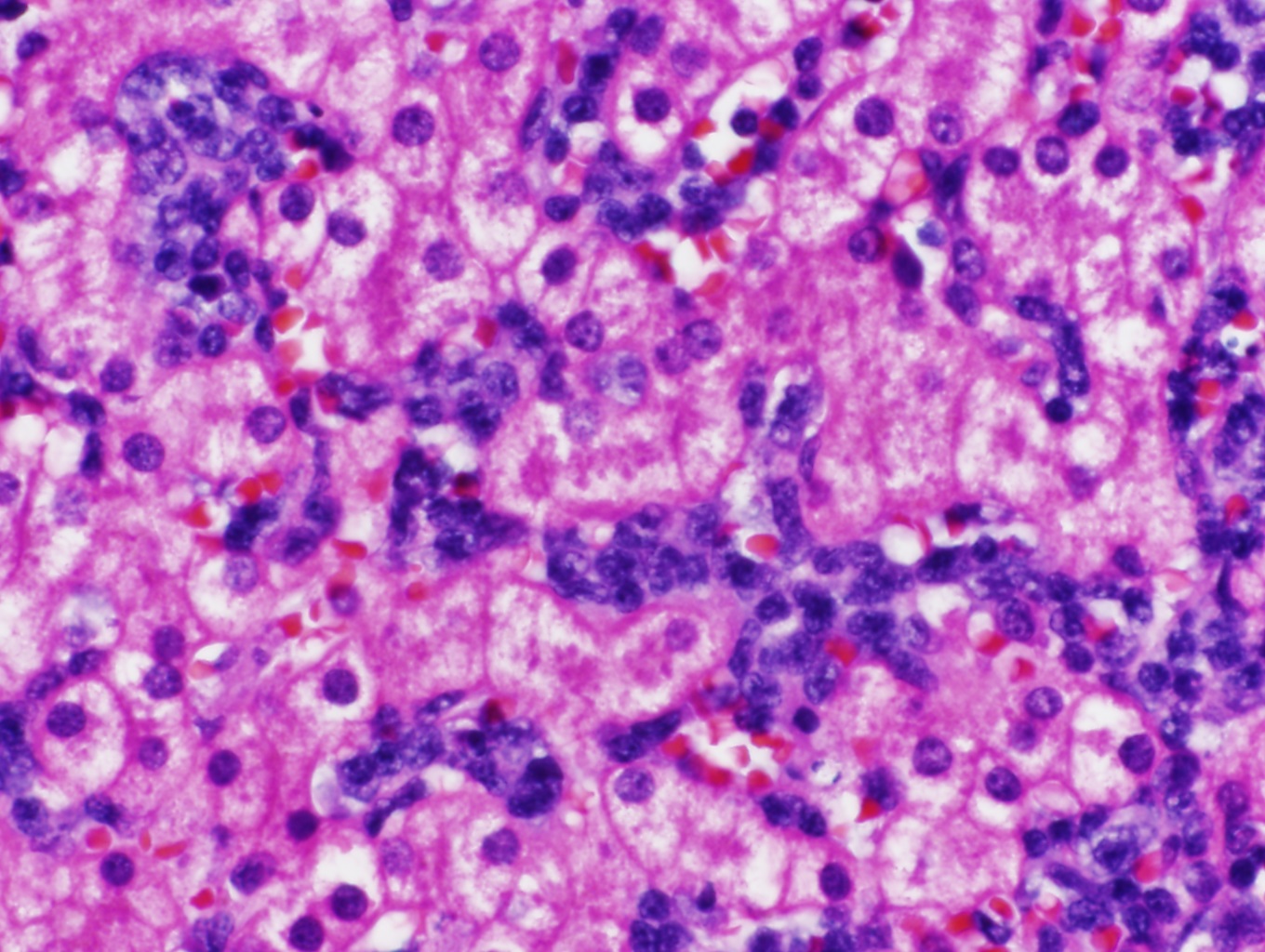

- Diagnostic study: Liver biopsy is crucial for diagnostic dilemmas, eg, differentiating autoimmune hepatitis from NASH in obese patients with abnormal liver function tests and positive autoimmune serology. Wilson disease is traditionally called the "great masquerader" due to its varied presentations. Quantifying copper on the liver biopsy specimen helps clinch the diagnosis. Additionally, liver biopsy is very useful in overlap syndromes, eg, autoimmune hepatitis with primary biliary cholangitis. Its role in the post-liver transplant setting cannot be overemphasized, as liver biopsy is very helpful in evaluating abnormal liver function tests in the immediate post-transplant setting. Vascular pathologies or infections help guide management, differentiating rejection from a recurrence of underlying diseases such as hepatitis C infection. Diagnostic challenges like differentiating cholangiocarcinoma from hepatocellular cancer can be made with liver biopsy in atypical cases. (see Image. Liver Biopsy)

- Prognosis: Liver biopsy can be a prognostic tool for several diseases. In NASH, the presence of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis has important prognostic considerations. Similarly, in diseases such as hemochromatosis, the presence of cirrhosis predicts an increased risk of developing hepatocellular cancer. Although now largely replaced by noninvasive markers, the presence of fibrosis has significant prognostic implications for patients with chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis C infection.

- Treatment: Liver biopsy plays a sentinel role in patients with autoimmune hepatitis being treated with steroids and immunomodulators. The presence of histologically active disease is associated with a high risk of relapse if treatment is stopped. A marked improvement in liver histology is observed if patients are taking treatment; therefore, histologic examination can help monitor compliance.

Contraindications

Few contraindications to liver biopsy have been established.[7] Most contraindications are relative, as they are both technique—and operator-dependent. Absolute and relative contraindications include:

- Absolute contraindications

- Uncooperative patient: Patients should be counseled thoroughly about the procedure and informed consent taken. Uncooperative patients can increase the risk of complications. If a liver biopsy is required, it can be performed under anesthesia.

- Increased risk of bleeding: In general, liver biopsy is not attempted if the INR is >1.5 or the platelet count is <60,000. Such patients may require correction of abnormal parameters before attempting a biopsy.

- Vascular tumors of the liver: Liver biopsy is associated with an increased risk of bleeding in presumed vascular tumors.

- Relative contraindications

- Ascites: Percutaneous biopsy is complex and associated with an increased risk of complications in ascites. The transvenous route is preferred.

- Morbid obesity: The procedure is much more challenging in morbidly obese patients due to interference by adipose tissue. The transvenous route is preferred.

Equipment

Aspiration or cutting needles can be used for liver biopsies, with 16- to 18-gauge needles most commonly used. Newer, automated versions of these needles are also available. While using aspiration needles, suction with a syringe is typically applied to obtain liver core tissue. This can result in fragmentation and inadequate specimens, especially in patients with underlying cirrhosis.

Some cutting types have a needle and outer cutting sheath, which when propelled beyond the needle, cuts, and traps tissue within the needle hollow. The cutting technique allows for better sampling and less tissue fragmentation, while the procedure is quicker and has less risk for complications when using the aspiration technique.

Preparation

Most liver biopsies are now conducted on an outpatient basis. However, the outpatient center where a liver biopsy is performed should ideally have easy access to an inpatient stay, laboratory, and blood bank services. Clinicians should consider scheduling outpatient liver biopsies in the morning so patients can be easily monitored in the facility for at least 4 hours after the procedure when all the support staff is available to care for any complications.

A brief history and physical examination should also be performed. A general consensus is to stop antiplatelet and anticoagulation medications before the procedure. The duration for stopping these drugs depends on the medication's mechanism of action. The indications for anticoagulation medications should be reviewed before advising cessation of therapy. Most centers stop these agents 5 days before the procedure. Most experts obtain a routine complete blood count with a coagulation profile to ensure platelet count is within normal range and no coagulopathy is present. Abnormalities of the above are associated with an increased risk of postprocedure bleeding. No routine antibiotics typically need to be given.

Patients can typically take a light snack 4 hours before the procedure. Experts have varying opinions about the duration of fasting. Anxious patients might require sedation; therefore, a longer duration of fasting is preferred. Additionally, written informed consent should be obtained.

Technique or Treatment

Liver specimens are primarily obtained using percutaneous, transvenous, laparoscopic, and plugged biopsy approaches.

Percutaneous Biopsy Techniques

Percutaneous biopsies can be performed using the following 3 techniques:

- Palpation or percussion method

- Imaging-guided

- Real-time image-guided

The patients are made to lie in a comfortable supine position. The right hand is placed under the head in a neutral position. The area of maximum dullness is identified by percussion over the right hemithorax. This is typically between the 6 and 9 intercostal spaces between the anterior and the midclavicular lines. Dullness is confirmed on both inspiration and expiration to avoid inadvertent pneumothorax. The location of the biopsy should be clearly marked.

Image-guided biopsy using ultrasound potentially increases the procedure's safety. Although image guidance minimizes the likelihood of obtaining inadequate specimens, this has not been shown conclusively to reduce the risk of significant complications. All patients who need liver biopsy should ideally have had an ultrasound before the biopsy to evaluate for the presence of Chilaiditi syndrome (ie, the presence of a small bowel between the liver and the abdominal wall), intrahepatic gallbladder and focal vascular lesions such as hemangioma. Image guidance is also helpful in a targeted biopsy (eg, lesions identified in imaging studies). The skin is prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. The overlying skin is anesthetized using 1% lidocaine. The peritoneum is also anesthetized by inserting the needle along the rib's upper border, avoiding vascular structures.

Transvenous Biopsy Techniques

Transvenous biopsy can be performed using transjugular or transfemoral approaches. This type of biopsy is beneficial in patients who are at high risk for complications from percutaneous biopsy, including those with ascites, obesity coagulopathy, sickle hepatopathy, suspected hepatic amyloidosis, and chronic kidney disease. Also, the free and wedged hepatic venous pressures can be measured at the same time, besides being able to opacify the hepatic vein, which makes this procedure very useful to diagnose and grade the severity of sinusoidal and post-sinusoidal portal hypertension and is also helpful in post-transplant settings.

Interventional radiologists typically perform this procedure under fluoroscopic guidance. The skin is anesthetized with 1% lidocaine over the puncture site, primarily the right internal jugular. The internal jugular vein is accessed, a sheath introducer is placed into the vein, and under fluoroscopic guidance, a catheter is advanced to the level of the right hepatic vein. Once the hepatic vein has been adequately visualized, a biopsy needle is threaded down the catheter and advanced into the liver parenchyma. Either of the above-described needles can be used. Biopsies obtained via this technique are often thinner than those obtained with the intercostal technique. If 3 to 4 passes are obtained, biopsies usually provide adequate tissue.

Laparoscopic Biopsy Techniques

The laparoscopic biopsy method is very safe in patients with chronic liver disease. It can be performed during surgery for different indications when the liver is found to be abnormal or in a planned manner. It allows visual inspection of the liver. It is most useful in targeted biopsies of liver masses, staging tumors, and in patients found to have inconclusive results using percutaneous and transvenous methods. Peritoneal biopsies can also be taken during laparoscopy in patients with unexplained ascites. This is most useful in diagnosing malignancy and infectious diseases like tuberculosis.

This technique can use both cutting and aspiration-type needles, and wedge biopsies can also be taken. Most centers perform laparoscopic biopsies in the operating room. However, diagnostic laparoscopy with moderate sedation can now be performed as an outpatient procedure. The patient is monitored closely during the procedure, and having anesthesia assistance is very helpful. A Veress needle is most commonly used. The use of nitrous oxide, as compared to carbon dioxide, has improved the tolerability of the procedure. Newer techniques extending from natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery can also be used to perform a liver biopsy.

Plugged Biopsy Techniques

A plugged biopsy is a modification of the percutaneous approach that can be used in patients at high risk for bleeding (eg, coagulopathy or thrombocytopenia). Although a transvenous biopsy can be obtained in this subset of patients, the plugged approach is used when a larger specimen size is desirable. The technique is similar to the percutaneous approach, except the biopsy tract is plugged with gel foam, collagen, or thrombin while the sheath is removed.

Complications

Liver biopsy is a very safe procedure in the hands of skilled operators. The overall rate of serious complications was approximately 1% in 2 large series, while in another, the overall mortality risk was estimated to be 0.2%. The usual indicators of complications requiring overnight hospital observation are severe abdominal or shoulder tip pain not relieved with 1 dose of parenteral analgesic, hypotension, or tachycardia following the procedure.[8]

Pain

Pain is the most common complication after liver biopsy. It can be seen in up to 84% of patients, most commonly at the biopsy site, the right shoulder (often indicating a subcapsular hematoma), or both. In most patients, pain is usually controlled with analgesics. However, severe persistent pain should alert the physician to investigate serious causes of pain, like bile peritonitis or hemorrhage. The patient may require admission and radiological assessment.

Bleeding Complications

The risk of fatal hemorrhage in patients without malignant disease is 0.04%, and the risk of nonfatal hemorrhage is 0.16%. In those with malignancy, the risk of nonfatal hemorrhage is 0.4%, and 0.57% for nonfatal hemorrhage. Bleeding complications typically fall into 3 main types: free intraperitoneal bleeding, intrahepatic and subcapsular hematomas, and hemobilia.

Free intraperitoneal bleed

Free intraperitoneal bleeding can be secondary to liver laceration with deep breathing during the intercostal procedure, perforation of distended portal or hepatic veins or aberrant arteries, or inadvertent puncture of a major intrahepatic blood vessel. The patients usually present with hemodynamic instability, severe abdominal pain, and a rapid drop in hemoglobin. Early recognition of this complication is imperative. The patient should be admitted and resuscitated, and both interventional radiology and a surgeon should be consulted. Angiographic embolization is usually successful in controlling the bleeding, but in rare cases, surgical intervention might be required, particularly in the transplant patient who carries a higher risk for significant bile duct injury with arterial embolization. Rarely, bleeding can be intrathoracic from an intercostal artery.

Intrahepatic and subcapsular hematoma

Intrahepatic and subcapsular hematoma can be seen even in asymptomatic patients. Bleeding usually presents with pain, tachycardia, and a mild drop in hemoglobin with a rise in serum transaminases. If large, they can cause right upper quadrant tenderness and hepatomegaly and appear as triangular hyper-dense segments in the arterial phase of the CT scan. Most patients can be managed with conservative treatment, and radiological or surgical intervention is rarely required.

Hemobilia

Hemobilia usually presents with the classical triad of gastrointestinal bleeding, biliary pain, and jaundice. The bleeding is typically arterial in origin but can be venous in patients with preexisting portal hypertension. Hemobilia can vary in severity from the occult to exsanguinating hemorrhage. This bleeding complication rarely presents acutely and most commonly presents after a median of 5 days with the gradual erosion of a biopsy-induced hematoma or pseudoaneurysm into the bile duct. The presentation can vary from hemodynamically significant bleeding to chronic anemia. Imaging or endoscopy can make a diagnosis. Treatment depends on the severity of the bleed. Hemodynamically significant radiologic intervention may be required. ERCP might be needed in some cases to remove clotted blood from the bile duct, causing obstruction and cholangitis.

Transient Bacteremia

Transient bacteremia is usually clinically insignificant except in patients with obstructive jaundice, like primary sclerosing cholangitis, or in the post-transplant setting. Currently, no prophylactic antibiotic treatment recommendations have been established, and treatment can be offered on a case-by-case basis.

Bile Peritonitis

Bile peritonitis can occur with the inadvertent puncture of the gallbladder or in patients with obstructive jaundice and dilated bile ducts. It usually presents with abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis, but bile peritonitis can also be painless in some patients. Biliary scintigraphy demonstrates the leak. Treatment generally includes fluids and antibiotics. Very rarely, endoscopic procedures like ERCP or surgery may be required.

Miscellaneous Complications

Cardiovascular complications, especially in patients with preexisting heart disease, arteriovenous fistula, and pneumothorax, are other rare reported complications. Carcinoid crisis can occur after the percutaneous biopsy.

Clinical Significance

Postprocedural Biopsy Considerations

Patient factors

The patient is usually kept in the right decubitus position. The duration of observation varies across centers, ranging from 1 hour to 6 hours. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines recommend 2 to 4 hours of observation. The vital signs are monitored every 15 minutes for the first hour, every 30 minutes for the next hour, and hourly till discharge. Most complications of liver biopsy usually occur within the first 1 to 3 hours after biopsy or within 24 hours. Hence, the patient should have a dependent individual stay overnight after the procedure. The patient should be hospitalized if any complications are associated with the procedure, including pain requiring more than 1 dose of analgesia within the first 4 hours of observation following the procedure.

Adequacy of specimen

Liver diseases can be patchy; therefore, biopsy specimens may not represent the underlying pathology. Obtaining a liver biopsy specimen adequate enough to allow detailed interpretation is critical. This means the biopsy should be large enough to view a representative amount of parenchyma and several portal tracts. The number of portal tracts is proportional to biopsy size. Obtaining more than 1 core increases the diagnostic yield but at the cost of increased complications. Biopsies taken with a 16-gauge needle facilitate obtaining larger specimen sizes.

Most experts agree that a specimen with 11 portal tracts about 2 cm long is adequate for evaluation. An alternative approach should be considered if an adequate specimen is not obtained after 2 passes. Thus, "long and wide (ideal size is 3 cm long after formalin fixation obtained with a 16-gauge needle) biopsies are desirable."[9] A cutting needle is preferable to a suction needle if the physician suspects cirrhosis. Although several noninvasive markers are now available, histological evaluation of the liver will remain an essential tool in assessing disease and is a safe procedure for skilled operators with relatively few complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective liver biopsy care requires a coordinated, interprofessional approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals. The procedure, typically performed by a radiologist, gastroenterologist, or general surgeon, must be followed by vigilant post-procedure monitoring by nurses. This includes assessing vital signs, abdominal distension, and pain levels to detect complications such as bleeding, which can occur up to 24 hours post-biopsy. Pharmacists are crucial in managing medications that may affect coagulation, while advanced practitioners and physicians must ensure proper patient preparation and follow-up care. Strong interprofessional communication and collaboration are essential to enhance patient-centered care, safety, outcomes, and overall team performance during liver biopsy management.