Introduction

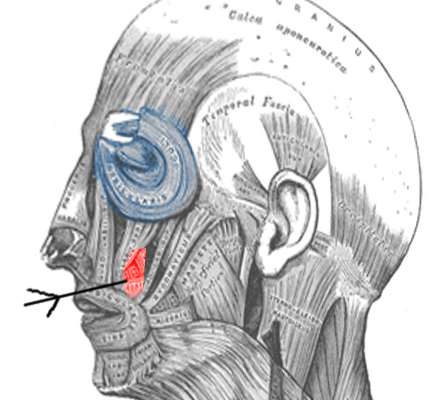

The levator anguli oris (LAO) is a muscle of facial expression that elevates the mouth's corners (see Image. Levator Anguli Oris). This muscle works with the zygomaticus major and minor, levator labii superioris, and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi to provide upper dental show when smiling and maintain the upper lip's resting tone and position.

While the LAO is not the most critical of the smile muscles, unilateral LAO paralysis can lead to noticeable smile asymmetry, impacting a person's quality of life.[1] Facial reconstructive surgeries involving the upper lip and facial nerve must consider this muscle, which aids in proper speech and mastication while contributing to facial aesthetics. Understanding the LAO's anatomy is essential in treating various cosmetic and functional impairments.

Structure and Function

The modiolus is a fibromuscular structure in the oral commissure lateral to the orbicularis oris at the corner of the mouth. The LAO's fibers travel anteroinferiorly and insert into the modiolus. The LAO is located in the deepest mimetic muscle layer along with the buccinator and mentalis, originating roughly 1 cm inferior to the infraorbital foramen within the maxilla's canine fossa. The LAO muscle fibers form an angle of approximately 37° with those of the more lateral zygomaticus major muscle. Other muscles attaching to the modiolus are the zygomaticus major, risorius, buccinator, depressor anguli oris, and orbicularis oris. These muscles pull the oral commissure in different directions, permitting facial expression variations.[2]

The LAO's primary function is to elevate the mouth's corners, achieved in concert with the zygomaticus major muscle. These muscles raise and lateralize the oral commissure, moving it obliquely, superiorly, and laterally. Variations in the contributions of these 2 muscles to the oral commissure's movements define an individual's unique smile. Other contributors to the upper lip's elevation are the levator labii superioris (also called "quadratus labii") and levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscles, which move the lip superiorly. The zygomaticus minor muscle inserts on the orbicularis oris muscle more medially than the zygomaticus major muscle but still has an oblique vector of pull.[3]

Embryology

The LAO muscles develop alongside the other facial mimetic muscles, beginning in the 3rd to 4th week of development.[4] The facial expression muscles arise from the 2nd branchial arch, which also gives rise to the facial nerve, stapedial artery (a temporary structure in most people), and Reichert cartilage. The Reichert cartilage forms the stylohyoid ligament, lesser hyoid cornu, and temporal styloid process.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

External carotid artery branches supply most of the face, while the internal carotid artery contributes to the periocular region's circulation. The facial artery, a large external carotid artery branch, arises from the neck's carotid triangle, traverses the mandible, and continues anterosuperiorly toward the lower face. Various small branches of the facial, maxillary, and superficial temporal arteries—vessels originating from the external carotid artery— supply the LAO.[6]

The facial artery gives off the lateral nasal artery, which crosses and then runs medially to the LAO. The maxillary artery gives rise to the infraorbital artery, which runs with the infraorbital nerve (CN V2) and emerges from the maxilla through the infraorbital foramen, just superior to the LAO. The superficial temporal artery's transverse facial branch also supplies the midfacial musculature. Some of the transverse facial artery's terminal branches may feed the LAO.

The LAO muscle's venous drainage predominantly flows into the facial vein, which empties into the internal jugular vein. Any blood draining back through the infraorbital vein reaches the pterygoid plexus and drains into the retromandibular vein, which frequently empties into the internal and external jugular veins.[7] Lymphatic vessels follow the facial vein and drain into the preauricular, infraauricular, parotid, nasolabial, buccinator, submandibular, submental, internal jugular, and anterior jugular basins and, ultimately, into the cervical lymph nodes.[16]

Nerves

The facial nerve provides motor control to the facial expression muscles, posterior digastric muscle belly, stylohyoid, and stapedius. Upon emerging from the temporal bone, the facial nerve travels through the parotid gland, separating the deep and superficial lobes, and continues distally beneath the face's superficial musculoaponeurotic system. The mimetic muscles are contiguous with this musculoaponeurotic layer. Thus, facial expression muscles, except the buccinator, mentalis, and LAO, are innervated from their deep surfaces. The buccinator, mentalis, and LAO lie deeper within the face and are innervated from their superficial surfaces by the facial nerve's terminal buccal branch.[8]

Surgical Considerations

The LAO's medial position in the midfacial area makes it unlikely to be injured iatrogenically, even during major facial procedures like rhytidectomy. However, lateral rhinotomy or Weber Ferguson approaches to midfacial pathology may risk muscle injury, edema, or inflammation. Primary LAO lesions are rare and may be addressed via an intraoral approach.

The LAO, mentalis, and buccinator lie deep to the rest of the facial expression muscles and are innervated from their deep surface. While few surgical approaches involve dissecting between the LAO and the overlying zygomaticus minor muscle, the terminal facial nerve branches' relationship to these muscles should be considered when operating in the medial midface to avoid inadvertent LAO denervation.[9]

The LAO is crucial in maintaining the oral commissure's resting position. Thus, this muscle has been proposed as a target for midfacial rejuvenation procedures, namely plication via an intraoral incision to elevate the corner of the mouth. This technique may also be valuable in flaccid facial paralysis management. The LAO is a component of interest during lip repositioning or reconstructive surgeries. The muscular and closely associated mucosal component makes the LAO and depressor anguli oris ideal tissue donors for lip defects, especially because sphincter tone can be maintained by transferring the innervated muscle.[10][11]

In another reconstructive application, the LAO has been employed as a pedicle for transferring regional flaps into nasal defects. The flap is raised via a nasolabial fold incision, which includes the skin, inferior LAO aspect, and intraoral mucosa if necessary. The flap is then tunneled into the ipsilateral nasal defect, with the remaining muscle attached superiorly to the maxilla.[12]

Clinical Significance

The literature describes several uses of LAO in aesthetic and functional surgery. The LAO muscle is a valuable landmark in determining volumizing injection locations with optimal aesthetics and safety.[13] The LAO is crucial to producing a natural-appearing, dentate, or "Duchenne" smile, without which people have difficulty expressing emotion and maintaining human social connection.[14]