Introduction

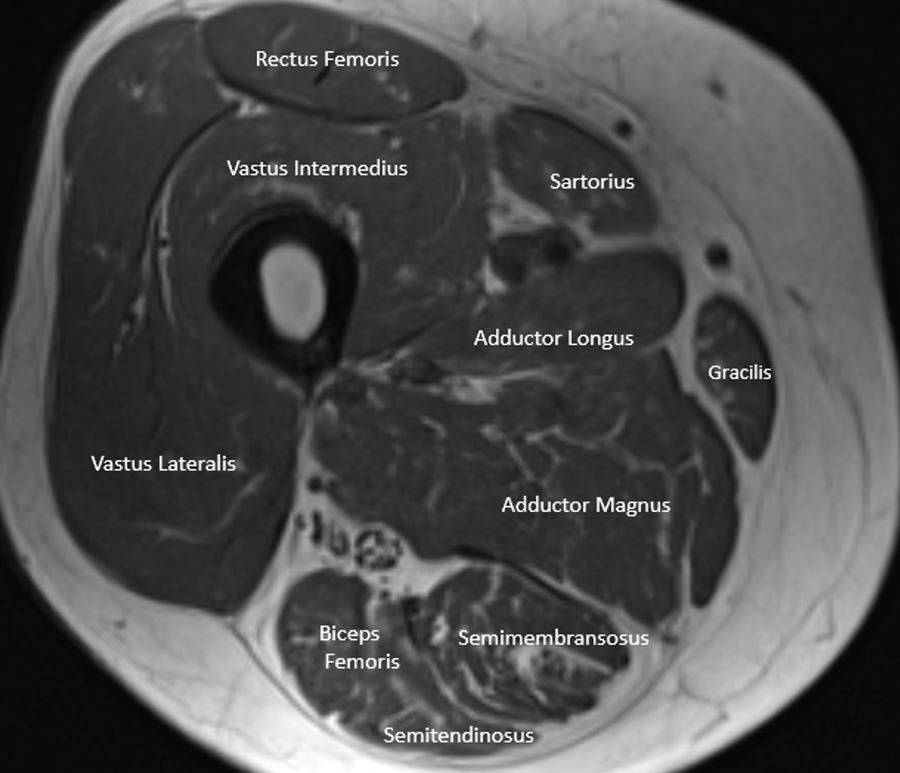

The thigh region is essential to the proper postural stability and locomotion of humans and is also a key conduit for neurovascular structures that pass from the abdomen to the lower limbs (see Image. Cross-Section of the Thigh). The thigh muscles are divided into groups based on location – the anterior, medial, and posterior compartments - each affording the lower limb different functional movements. Understanding the main function of each group of muscles and the unique properties of muscles within a group helps identify different disorders based on the physical examination and patient history.[1][2]

Structure and Function

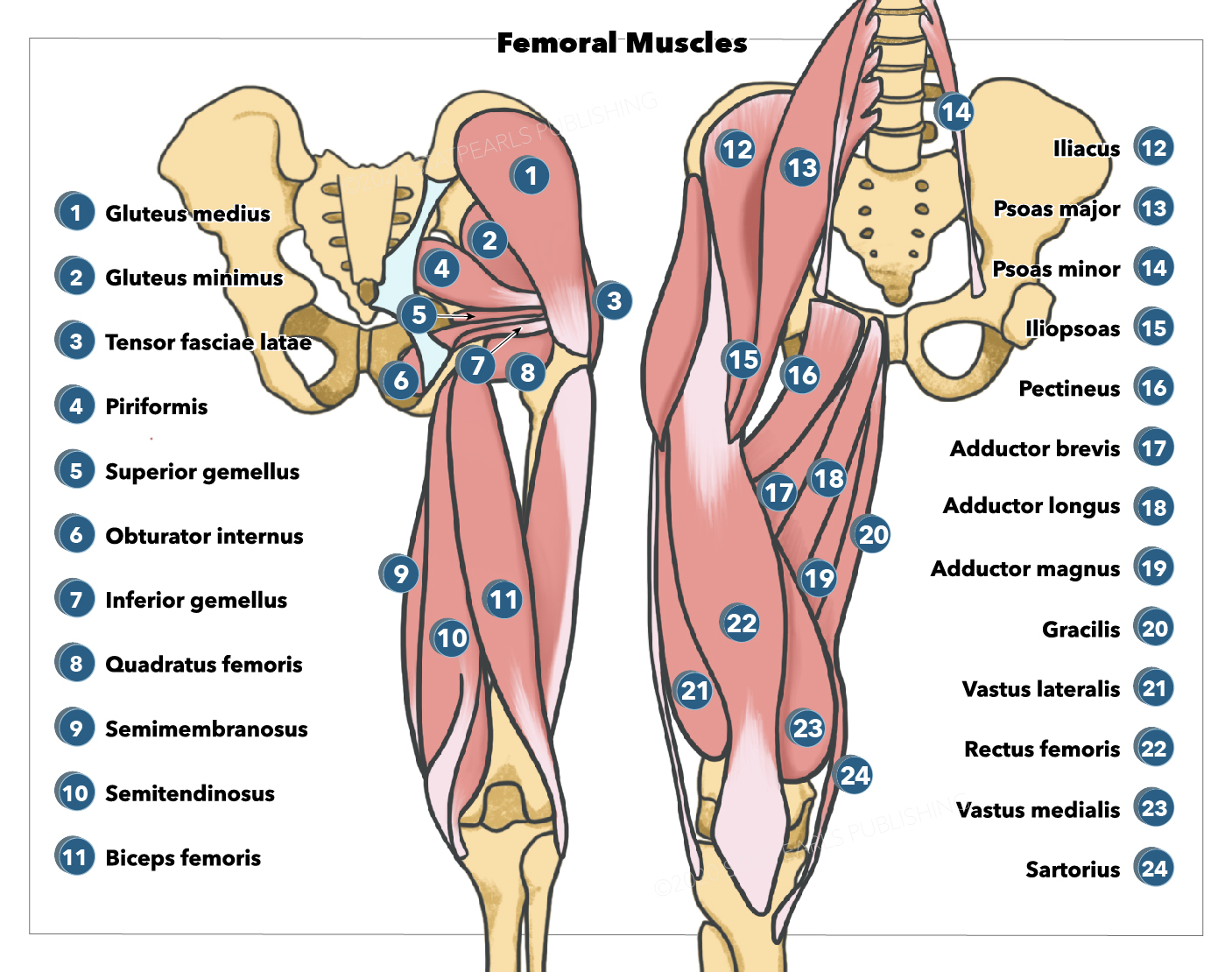

The thigh muscles are divided into 3 compartments: the anterior, medial, and posterior thigh muscles. Each compartment contains multiple muscles that broadly share the same functional action, innervation, and arterial supply (see Image. Gluteal and Femoral Muscles).[3] The muscles of the gluteal region are also important to the function of the lower limb but are considered in a separate topic.

Anterior Compartment of Thigh Muscles

This compartment includes 2 subgroups of muscles: those that are hip flexors and hip abductors, and the knee extensors (called the quadriceps collectively)

Hip Flexors

The hip flexors comprise the iliacus, psoas major, sartorius, and pectineus. The iliacus arises from the iliac fossa within the bony pelvis and inserts at the upper part of the femur. Psoas major arises from the lower border of the T12 vertebra to the L5 vertebra, and it extends downwards under the inguinal ligament with iliacus to inserts beside it at the lesser trochanter of the femur. The sartorius muscle is the longest in the body and crosses from the anterior superior iliac spine inferomedially to insert at the supper medial part of the tibia. The pectineus is a smaller muscle that arises at the eponymous pectineal line of the pubis and inserts at the upper femoral shaft behind the lesser trochanter. The iliacus and the psoas are both flexors of the thigh in relation to the torso and receive blood supply from the lumbar branch of the iliopsoas of the internal iliac artery. Innervation to the iliacus is by the muscular branch of the femoral nerve (L1 through L3), while the direct fibers of L1 innervate the psoas through the L3 lumbar plexus. The sartorius is unique in that it flexes and laterally rotates the hip joint and flexes the knee, is innervated by the femoral nerve (L2 through L4), and receives blood supply from the muscular branches of the femoral artery. The pectineus is also unique as it adducts the thigh and flexes the hip; the femoral nerve usually innervates it but is sometimes innervated by the obturator nerve. Its blood supply is from the medial circumflex femoral branch of the femoral and obturator artery.

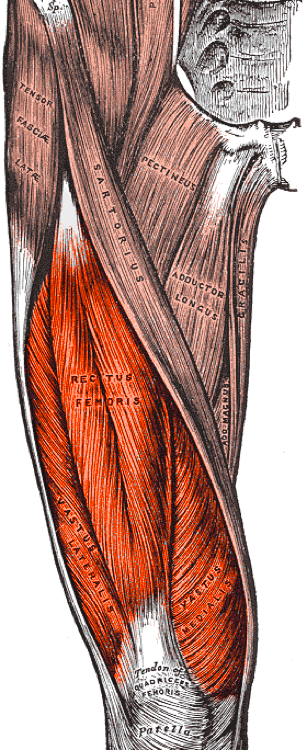

Knee Extensors (quadriceps)

The overall function of the quadriceps group is knee extension via their distal attachments at the patellar tendon (see Image. Right Quadriceps Femoris, Anterior View). All muscles in this group are innervated by the femoral nerve (L2-L4) and supplied by the lateral femoral circumflex artery (except the vastus medialis, which receives its blood supply from the femoral artery, profunda femoris artery, and superior medial genicular branch of the popliteal artery.[4]

The 4 muscles in the extensor group are the vastus lateralis, vastus intermedius, vastus medialis, and rectus femoris. All 4 function to extend the knee, but the rectus femoris is also an accessory flexor of the hip. The rectus femoris has 2 heads - the reflected head and the straight head - from just above the acetabulum and the anterior inferior iliac spine, respectively. The vastus lateralis arises from the intertrochanteric line, the greater trochanter, and the linea aspera. The vastus intermedius arises from the anterolateral part of the upper femur. The vastus medialis arises from the intertrochanteric line and the linea aspera. All these muscles insert via the common quadriceps tendon into the base and sides of the patella, thus exerting their extension action on the knee joint.

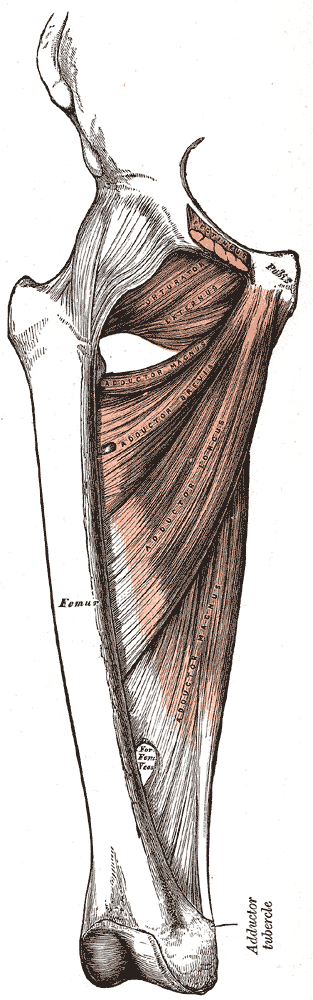

Medial Compartment of the Thigh (adductors)

The adductors of the thigh are the adductor longus, adductor brevis, magnus, and gracillis (see Image. Medial Compartment of the Thigh). The longus, brevis, and magnus all adduct and flex the thigh. The longus and brevis rotate the hip joint laterally and share the blood supply of the obturator and medial circumflex femoral arteries. The longus is unique because it is innervated by the anterior division of the obturator nerve (L2, L3, L4). The unique feature of the adductor brevis is that the innervation can be from either the anterior or posterior division of the obturator nerve. The adductor magnus differs as it is considered the most powerful adductor of the thigh; the superior horizontal fibers flex the thigh while the vertical fibers extend it. The magnus is also different due to dual innervation and different blood supply. The obturator nerve innervates most of the magnus, while the vertical (hamstring) portion is innervated by the tibial nerve (L2 through L4).[5] The magnus blood supply is from the medial circumflex femoral artery, inferior gluteal artery, first through fourth perforating arteries, obturator artery, and some superior muscular branches of the popliteal artery. The gracilis medially rotates the tibia on the femur and flexes the knee. Innervation is by the anterior division of the obturator nerve (L2, L3) and receives its blood supply from the obturator artery, medial circumflex artery, and muscular branches of the profundal femoris artery.

Gracilis arises from the inferior ramus of the pubis and attaches to the upper medial tibial shaft close to the sartorius. The adductor longus arises from the body of the pubis and inserts as a flat tendon at the linea aspera of the femur. The adductor brevis also arises from the body of the pubic bone and inserts into the linea aspera behind the adductor longus insertion. The adductor magnus has 2 parts: the hamstring and the adductor portion. The hamstring part originates at the ischial tuberosity before inserting at the adductor tubercle of the femur. The adductor part originates at the ischiopubic ramus and inserts along the supracondylar line, the linea aspera, and the gluteal tuberosity.[6]

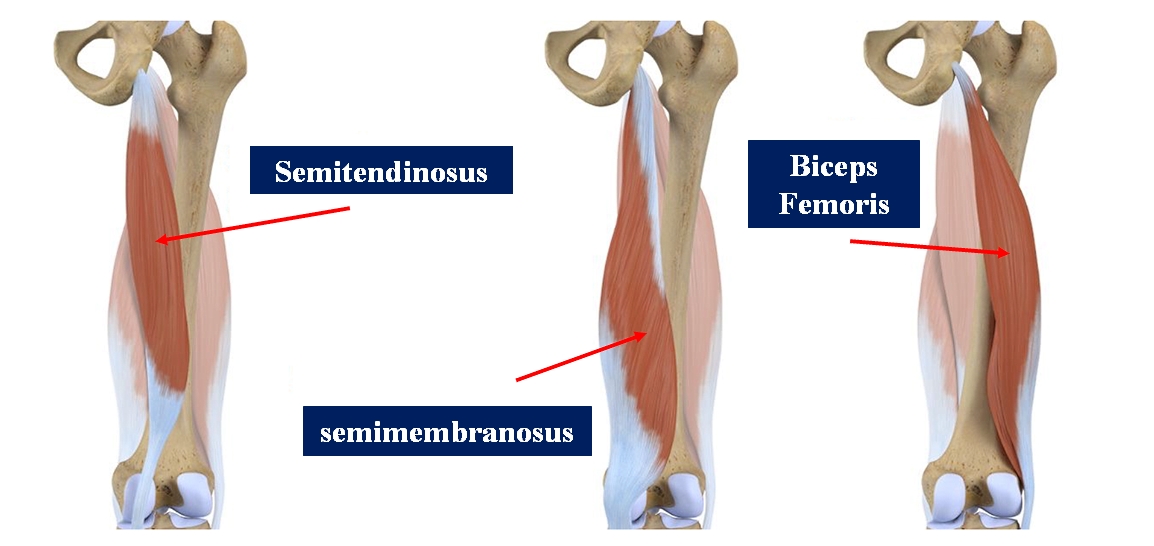

Posterior Compartment of the Thigh (hamstrings)

The hamstrings comprise the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and long and short heads of the biceps, all of which flex the knee (see Image. Hamstring Muscles). Both heads of the biceps femoris also rotate the tibia laterally. The long head additionally extends the hip. The semitendinosus and semimembranosus extend the thigh and rotate the tibia medially, especially when flexing the knee.[7][8] All hamstring muscles except the short head of the biceps femoris are innervated by the tibial nerve (L5, S1, S2), which is innervated by the common peroneal nerve. Blood supply to all 4 muscles is from the perforating branches of the profunda femoris artery, inferior gluteal artery, and the superior muscular branches of the popliteal artery.

Semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and the long head of biceps femoris all arise from the ischial tuberosity. The short head of the biceps femoris arises from the linea aspera of the femur. It inserts as a common tendon with the long head of the biceps femoris at the head of the fibula. The semimembranosus inserts at the medial condyle of the tibia, and the semitendinosus inserts at the medial part of the upper tibial shaft.[9]

Embryology

Limb bud development begins after the mesenchymal cells are activated in the lateral plate of the mesoderm. The lower limbs develop after the development of the upper limbs begins. This process usually starts at the 4-week gestational period, with the limbs well differentiated by weeks 8 to 10.[10]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The lower extremity veins are described based on their position relative to the fascial compartment. The superficial veins are above the deep fascia and drain the cutaneous circulation. The deep veins are below the fascia and drain the musculature.

The superficial veins include the reticular and the greater and lesser saphenous veins. The reticular veins are located between the saphenous fascia and dermis, mainly draining the skin and subcutaneous tissue. These veins communicate with the saphenous system through perforator veins. The greater saphenous vein lies medially in the thigh, anastomosing with the common femoral vein approximately 3 to 4 cm inferior and lateral to the pubic tubercle. The greater saphenous vein is located directly on the muscular fascia in the saphenous compartment, a sub-compartment of the superficial compartment.[11]

The major deep veins of the thigh follow the same nomenclature as the lower leg arteries except for the femoral vein, which is an extension of the popliteal vein. The main artery of the thigh is the femoral artery. The femoral artery is an extension of the external iliac artery and becomes the femoral artery after it crosses under the inguinal ligament. The main branches include the medial circumflex, lateral circumflex, and profunda femoris artery.[12] The medial circumflex wraps around the posterior side of the femur. It supplies the head and neck of the femur, while the lateral circumflex wraps around the lateral anterior aspect of the femur. The perforating branches comprise 3 or 4 arteries perforating the adductor magnus supplying the medial and posterior thigh.[13]

Nerves

Both the lumbar and sacral plexus supply innervation to the lower limbs. The sacral plexus gives rise to the sciatic nerve (L4 through S3), posterior femoral nerve (S1 through S3), superior gluteal nerve (L4 through S2), and inferior gluteal nerve.[14] The sciatic nerve innervates the semimembranosus, semitendinosus, and adductor magnus. It then divides into the tibial nerve, innervating the flexors of the knee, extensors of the ankle, flexors of the toes, and skin over the posterior surface of the leg. The other half of this division is the common peroneal nerve supplying innervation to the short head of the biceps femoris, fibularis, tibialis anterior, extensors of the toes, the skin over the anterior surface of the leg, and dorsal surface of the foot. The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve supplies sensation to the perineum's skin and the thigh's posterior surface. The superior gluteal nerve supplies motor function to the abductors of the hip, while the inferior gluteal nerve innervates the gluteus maximus.

The lumbar plexus supplies innervation to the femoral (L2 through L4), lateral femoral cutaneous (L2, L3), obturator (L2 through L4), and saphenous nerves (L2 through L4). The femoral nerve supplies innervation (sensation and motor) to the anterior thigh. The obturator nerve provides sensory innervation to the medial thigh and motor function to the adductors. The saphenous and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves are both strictly sensory, innervating the medial aspect of the leg and lateral thigh, respectively.[15][16]

Surgical Considerations

Understanding the anatomy of the thigh is of utmost importance in the surgical setting for several reasons. Many of the approaches of the thigh are through intramuscular planes. Operating safely through these planes minimizes neurovascular injury during the perioperative period. If a complication occurs, understanding the anatomy allows the clinician to identify the pathology area promptly.[17] Understanding the origins and insertions of the different muscles gives the surgeon the knowledge to determine the appropriate tendinous portion of muscle utilized for grafts to prevent morbidity, as several thigh muscles are used for graft reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).[8] From an anesthesia perspective, peripheral nerve blocks are often performed during surgery to minimize pain postoperatively. The correct nerve must be identified to minimize patient discomfort and optimize pain control.

Clinical Significance

Understanding the anatomy of the thigh can assist the physician in identifying pathology during a physical exam. As part of the comprehensive history and physical examination, understanding specific muscle functions and actions aids the clinician in identifying and differentiating isolated/focal injuries from more widespread or systemic conditions. The latter range from peripheral nerve entrapment to spinal conditions and pathologies (eg, radiculopathy with associated nerve root compression) and medically relevant conditions (eg, genetic conditions, diabetes, neuropathy, or inflammatory conditions).