Continuing Education Activity

Kayser-Fleischer rings are a common ophthalmological finding in patients with Wilson disease—a genetic disorder that affects copper metabolism in the body. Usually evident in late childhood or early adolescence, these rings develop due to excess copper deposition on the inner surface of the cornea within the Descemet membrane. Occasionally, Kayser-Fleischer rings may manifest in patients with other conditions, such as primary biliary cholangitis, neonatal cholestasis, and liver disease. Additional complications include psychiatric illnesses, neurological symptoms, cardiomyopathy, infertility, and hemolytic anemia. Without proper treatment, Wilson disease can progress to cirrhosis and liver failure, ultimately resulting in death.

Kayser-Fleischer rings are not specific to Wilson disease, and they can be found in patients with primary biliary cholangitis and children with neonatal cholestasis. These rings do not typically cause visual impairment and can be resolved through treatment. However, they may reappear with disease progression, serving as valuable indicators of the patient's response to therapy and adherence to treatment. A slit-lamp examination is essential to diagnose Kayser-Fleischer rings, especially in the early stages, unless the rings are visible to the naked eye in conditions of severe copper overload. Prompt recognition of Kayser-Fleischer rings, evaluation of the underlying cause, and management of excess copper levels are crucial in reducing patient morbidity and mortality. This activity reviews the etiology, pathophysiology, evaluation, and management of Kayser-Fleischer rings, highlighting the critical roles of the interprofessional healthcare team in ensuring the timely evaluation of the condition and treatment of affected individuals.

Objectives:

Identify Kayser–Fleischer rings during ocular examinations and understand their potential occurrence in conditions such as Wilson disease, primary biliary cholangitis, neonatal cholestasis, and liver disease.

Implement a slit-lamp examination to diagnose Kayser-Fleischer rings, especially in early stages or severe copper overload.

Apply knowledge of the broader implications of Kayser-Fleischer rings, including associated complications and outcomes.

Collaborate with interprofessional healthcare teams to ensure comprehensive evaluation and treatment of patients with Kayser–Fleischer rings.

Introduction

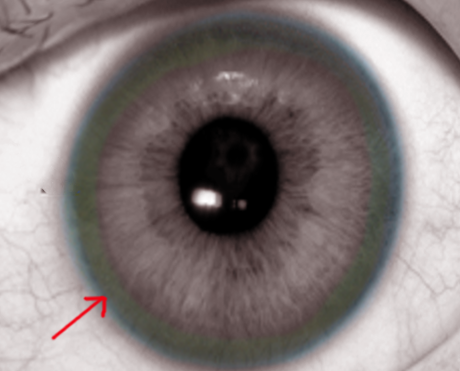

Kayser-Fleischer rings are a common ophthalmological finding in patients with Wilson disease—a genetic disorder that affects copper metabolism in the body. Usually evident in late childhood or early adolescence, these rings develop due to excess copper deposition on the inner surface of the cornea within the Descemet membrane (see Image. Kayser-Fleischer Rings From Copper Deposits). Occasionally, Kayser-Fleischer rings may manifest in patients with other conditions, such as primary biliary cholangitis, neonatal cholestasis, and liver disease. Additional complications include psychiatric illnesses, neurological symptoms, cardiomyopathy, infertility, and hemolytic anemia. Without proper treatment, Wilson disease can progress to cirrhosis and liver failure, ultimately resulting in death.

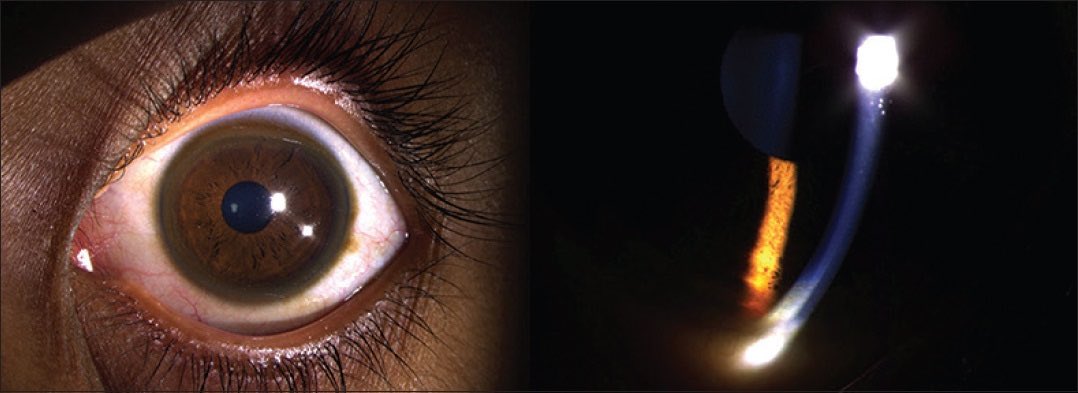

Kayser-Fleischer rings are not specific to Wilson disease, and they can be found in patients with primary biliary cholangitis and children with neonatal cholestasis. Despite initial beliefs that the rings were caused due to silver buildup, in 1934, researchers discovered that the rings actually contained copper. Kayser-Fleischer rings do not typically cause visual impairment and can be resolved through treatment. However, they may reappear with disease progression, serving as valuable indicators of the patient's response to therapy and adherence to treatment. A slit-lamp examination is essential to diagnose Kayser-Fleischer rings, especially in the early stages, unless the rings are visible to the naked eye in conditions of severe copper overload (see Images. Kayser-Fleischer Rings and Kayser-Fleischer Rings (Labeled)).[1][2][3][4][5] Prompt recognition of Kayser-Fleischer rings, evaluation of the underlying cause, and management of excess copper levels are crucial in reducing patient morbidity and mortality.

Etiology

Kayser-Fleischer rings are brown or grayish-green rings that appear to encircle the peripheral cornea, overlying the iris. They result from copper deposition in the Descemet membrane of the cornea due to the excess accumulation of copper from cholestasis, liver disease, or errors in copper metabolism.

Epidemiology

Wilson disease is globally prevalent at a rate of 1 case per 30,000 live births. Almost 95% of patients exhibiting neurological manifestations of Wilson disease display Kayser-Fleischer rings. Among those with non-neurological disease, approximately 50% may have the rings, along with 10% to 40% of asymptomatic patients and 63% of children with Wilson disease. Although Kayser-Fleischer rings can possibly occur, they are uncommon in individuals with other underlying conditions to exhibit those rings.

Pathophysiology

Kayser-Fleischer rings are caused by the deposition of excess copper on the inner surface of the cornea's basement membrane or the Descemet membrane, which extends into the trabecular meshwork. Copper infiltrates from the aqueous humor through the endothelial cells into the Descemet membrane due to its affinity for the basement membrane.

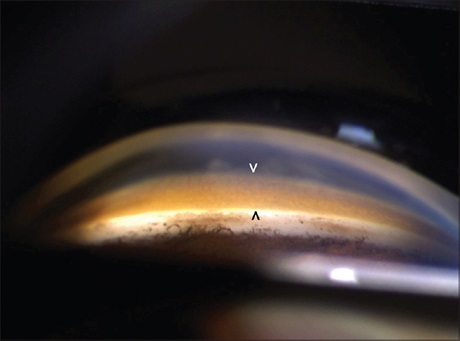

Copper is present throughout the cornea and deposits as a granular complex with sulfur, imparting the ring's characteristic color. As a result of fluid streaming, copper accumulates both superiorly and inferiorly before involving the iris circumferentially. In addition, copper may also be deposited in the anterior and posterior capsule lens, which may lead to sunflower cataracts with radiating centrifugal extensions. Notably, neither Kayser-Fleischer rings nor sunflower cataracts cause visual impairments. The deposition of excess copper in various other organs gives rise to the additional clinical manifestations of Wilson disease. Specifically, deposits in the basal ganglia contribute to the neurological and psychiatric manifestations.[6][7][8][9]

History and Physical

Kayser-Fleischer rings are generally asymptomatic, appearing bilaterally, with the upper portion of the cornea being the first to be affected. Over time, these rings spread circumferentially and appear as golden-brown rings in the peripheral cornea, originating at the Schwalbe line and extending less than 5 mm onto the cornea (see Image. Schwalbe Line). These rings may exhibit various colors, such as greenish-yellow, ruby red, bright green, or ultramarine blue.

Wilson disease should be suspected in individuals who present with the following conditions:

- Kayser-Fleischer rings on a routine eye examination

- A family history, particularly with a sibling or parent diagnosed with Wilson disease

- Unexplained and acquired Coombs-negative hemolytic anemia

- Neurological symptoms of unexplained origin

- Psychiatric disease with signs of hepatic or neurological disease

- Patients aged between 3 and 55 with unexplained serum aminotransferase elevation, chronic hepatitis with steatosis, poorly responsive autoimmune hepatitis, cirrhosis, or acute liver failure

Age alone should not be used as a criterion to disregard a diagnosis of Wilson disease. A few patients older than 55 present with neurological symptoms of Wilson disease, primarily when previous symptoms were unrecognized.

Evaluation

Kayser-Fleischer rings may not be easily visible on routine examination. In the initial stages, a slit lamp is generally necessary to identify the rings. However, visibility with the naked eye becomes possible as the disease progresses, especially in patients with lightly pigmented irises and severe copper overload. Therefore, a slit-lamp examination is imperative for diagnosis. Gonioscopy, which is considered the gold standard for diagnosing angle-closure glaucoma, uses a special lens for the slit lamp. This lens allows for the visualization of the angle and may also detect early Kayser-Fleischer rings.

The evaluation for Wilson disease includes ocular slit-lamp examination or anterior segment optical tomography, 24-hour urinary copper excretion, serum ceruloplasmin, serum aminotransferase, complete blood count, serum copper concentration, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in the presence of neurological symptoms, liver biopsy if diagnosis is uncertain, and genetic testing if liver biopsy is necessary and not possible or remains inconclusive.

Treatment / Management

Lifelong oral chelating agents, such as penicillamine and trientine, form the cornerstone of therapy for Wilson disease by binding excess copper and promoting urinary excretion. Zinc acetate is also utilized to prevent the excessive absorption of copper. During pregnancy, individuals may temporarily combine zinc acetate with chelators as maintenance therapy. Furthermore, upon diagnosis, patients should refrain from consuming shellfish, nuts, chocolate, mushrooms, and organ meats. Once treatment has been ongoing and stabilized, patients can gradually reintroduce some of these foods in moderation. Notably, dietary modifications alone are not sufficient for managing Wilson disease. Individuals experiencing acute liver failure will require urgent evaluation for liver transplant, as medical treatment alone is ineffective in such cases.[10][11]

Although Kayser-Fleischer rings typically disappear with treatment, they may reappear with disease progression. Their presence serves as valuable clinical indicators for monitoring treatment compliance. Chelation therapy leads to the disappearance of the rings in around 80% of patients over 3 to 5 years. Notably, liver transplantation represents a curative option for Wilson disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Although Kayser-Fleischer rings are most commonly associated with Wilson disease, they may also occur in various other conditions such as primary biliary cholangitis, multiple myeloma, chronic cholestasis, neonatal cholestasis, autoimmune hepatitis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, liver failure, and chronic liver disease.

The following conditions are included in the differential diagnosis of Wilson disease:

- Chronic liver disease occurs from various causes, such as viral hepatitis, alcohol use disorder, autoimmune hepatitis, drug-induced liver injury, hereditary hemochromatosis, and alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- Chronic hypertensive encephalopathy

- Glioma

- Japanese encephalitis

- Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma

- Tuberculosis meningoencephalitis

- West Nile encephalitis

- Primary biliary cholangitis

- Psychiatric illness

- Fleischer ring of keratoconus

Several key factors aid in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Individuals with Wilson disease and acute liver failure are prone to develop nonimmune hemolytic anemia. Individuals with chronic liver disease attributed to Wilson disease typically exhibit low ceruloplasmin levels, and almost all patients with neurological symptoms associated with Wilson disease present Kayser-Fleischer rings. These distinct findings contribute to distinguishing Wilson disease from other potential etiologies.

Prognosis

Wilson disease can be fatal if left untreated, often progressing to cirrhosis and complications of portal hypertension, such as ascites and variceal bleeding.[12] Neurological symptoms can progress to dystonia, akinesia, and mutism. However, early treatment leads to a favorable prognosis. Initiating treatment before the onset of cirrhosis and maintaining normal copper levels enables a normal life expectancy. Although liver enzyme levels usually normalize within 1 year of treatment, cirrhosis is permanent. Neurological symptoms may show improvement for up to 18 months, with some residual symptoms likely becoming permanent. Psychiatric symptoms typically improve concurrently with neurological symptoms.[13]

Complications

Copper can accumulate in various organs. Although the primary sequelae of Wilson disease predominantly affect the liver, CNS, and peripheral nervous system, other parts of the body can also be involved. Complications arising from excess copper deposition in Wilson disease include cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma secondary to cirrhosis, mood disorders, psychosis, sleep disturbance, cardiomyopathy, Fanconi syndrome, myopathy, arthropathy, hyperparathyroidism, infertility, sexual dysfunction, gigantism, nonimmune hemolytic anemia, ascites, and varices.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Kayser-Fleischer rings are abnormal deposits of copper in the eye. Although the rings may be visible to the naked eye, they often require a particular eye examination called a slit-lamp examination early on. Kayser-Fleischer rings are most commonly associated with a condition known as Wilson disease and may initially indicate an underlying problem. These rings do not cause vision disturbances, but they signify an excess of copper, which can lead to cirrhosis, psychiatric illnesses, and symptoms affecting the nervous system and other organs in the body.

Healthcare professionals will analyze blood and urine samples to determine whether the presence of rings is due to Wilson disease or another underlying condition. If these initial tests fail to yield sufficient information, patients may need to undergo additional assessments such as a liver biopsy, genetic testing, or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain.

Oral treatments along with diet changes are available for addressing excess copper in Wilson disease. However, dietary changes alone are not sufficient. Individuals affected by Wilson disease who undergo early treatment and sustain normal copper levels can achieve an average life expectancy. Lack of proper treatment will lead to death, primarily due to liver failure. Individuals facing liver failure may necessitate a liver transplant. In addition, patients with a family history of Wilson disease should inform their healthcare professional to explore potential testing options.[14]

Pearls and Other Issues

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive disorder that causes elevated levels of copper in affected organs due to the reduced excretion of copper, leading to copper toxicity. The reduced biliary excretion of copper may be due to a potential defect in copper's entry into lysosomes, while lysosomal copper delivery remains unaffected. Individuals with Wilson disease exhibit a low ceruloplasmin level, attributed to the absence of copper incorporation into apoceruloplasmin, which has a shorter half-life compared to copper-bound ceruloplasmin or holo-ceruloplasmin.

Clinical symptoms of Wilson disease are rarely present before the age of 5, and most untreated patients typically exhibit symptoms by the age of 40. Low concentrations of ceruloplasmin in the serum can result from various causes, including severe liver disease leading to reduced synthesis, nephrotic syndrome, protein-losing enteropathy, and intestinal malabsorption. Normal levels of serum ceruloplasmin do not exclude the possibility of Wilson disease. Approximately 15% of patients with Wilson disease may present normal ceruloplasmin levels, as it is an acute phase reactant. Elevated ceruloplasmin levels may occur in individuals with severe liver injury from any cause and in patients with elevated serum estrogen levels.

The diagnosis of Wilson disease is definitively established when there is evidence of Kayser-Fleischer rings, significantly elevated hepatic copper concentration obtained through a liver biopsy, and a low serum ceruloplasmin level, particularly in cases where the diagnosis is suspected.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Kayser-Fleischer rings are classic signs of Wison disease and result from copper deposition in the Descemet membrane of the cornea. In rare instances, patients with other conditions, such as primary biliary cholangitis, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and neonatal cholestasis, may also present with Kayser-Fleischer rings. Excess copper deposits throughout the body may cause cirrhosis, liver failure, and psychiatric illnesses, as well as various other complications, including death. Collaborative efforts among interprofessional healthcare team members are essential to ensure a prompt evaluation and diagnosis, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality in affected patients.

Clinicians across all specialties must understand the significance of Kayser-Fleischer rings, as they can be involved in almost every organ system and may likely develop cirrhosis and liver failure. Possessing the necessary clinical expertise for diagnosing Kayser-Fleischer rings and ensuring that each patient undergoes the appropriate evaluation and management for the underlying cause are essential in improving overall patient care.[4]

Wilson disease may present with a range of symptoms, including having elevated transaminase levels while being asymptomatic, acute liver failure or cirrhosis, acute nonimmune hemolytic anemia, psychosis or mood disorders, and exhibiting dystonia, dysarthria, or a Parkinsonian movement disorder. Healthcare professionals should consider Wilson disease when a patient presents with symptoms such as Kayser-Fleischer rings and a low ceruloplasmin level. Seamless interprofessional communication is crucial to ensure that affected patients receive the appropriate specialty input for a timely evaluation and diagnosis. Patients and caregivers require proper education regarding the necessity for lifelong treatment and adherence to dietary restrictions. This coordinated approach helps minimize diagnostic and treatment delays, leading to improved outcomes and patient-centered care, ultimately reducing the overall mortality risk.