Continuing Education Activity

Kaposi sarcoma is an interesting soft tissue tumor occurring in several distinct populations with a variety of presentations and courses. In its most well-known form, Kaposi sarcoma occurs in patients with immunosuppression, such as those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDs) or those undergoing immunosuppression due to an organ transplant. This activity reviews the cause, presentation and pathophysiology of kaposi sarcoma and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in its management.

Objectives:

- Describe the epidemiology of kaposi sarcoma.

- Review the presentation of kaposi sarcoma.

- Summarize the treatment options for kaposi sarcoma.

- Explain modalities to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members in order to improve outcomes for patients affected by kaposi sarcoma.

Introduction

Kaposi sarcoma is an interesting soft tissue tumor occurring in several distinct populations with a variety of presentations and courses. In its most well-known form, Kaposi sarcoma occurs in patients with immunosuppression, such as those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDs) or those undergoing immunosuppression due to an organ transplant. Initially described in 1872 by Moritz Kaposi, an Austro-Hungarian dermatologist in 5 patients with the multifocal disease,[1] human herpesvirus/Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (HHV-8) was discovered as a causative agent of Kaposi sarcoma as the AIDS epidemic progressed in the 1980s.[2] Four clinical forms emerged.

- Classic form occurring in elderly men of Mediterranean and Eastern European descent on the lower extremities

- Endemic African form with generalized lymph node involvement occurring in children

- HIV-related form occurring with patients not taking highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs

- Iatrogenic form in immunosuppressed patients also with diffuse involvement of the skin and internal organs

Each form has a differing natural history ranging from indolent to more aggressive and fatal in anaplastic varieties.[3]

Etiology

Human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) is present in all forms of Kaposi sarcoma.[4] HHV-8 interferes with many normal cell functions and requires cofactors like cytokines or specific proteins to result in the development of Kaposi sarcoma.[5] Other malignancies associated with HHV-8 include plasmablastic multicentric Castleman disease, primary effusion lymphoma, intravascular large B cell lymphoma, and occasionally angiosarcoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.[5]

Epidemiology

Classic Kaposi sarcoma has a male: female ratio 17:1 and occurs primarily in patients over 50 years old of Eastern European and Mediterranean descent. These patients are at greater risk for secondary malignancies.[6][7] The prevalence mirrors the distribution of HHV-8 throughout the world.[8] Within the United States, incidence has been stable around 1:100,000 since 1997.[9]

Endemic Kaposi sarcoma has the unusual predilection for the pediatric population and mirrors HHV-8 seropositivity.[6] The rates of seropositivity in pediatric patients vary extensively throughout Africa, from a low of 2% in Eritrea to almost 100% in the Central African Republic.[10] Following the HIV epidemic in Africa, the ratio of men to women with Kaposi sarcoma has fallen from 7:1 to 2:1.[11] Endemic Kaposi sarcoma is now the most common cancer in men and the second most common cancer in women with Uganda and Zimbabwe.[11]

HHV-8 seropositivity worldwide varies, with a high of 40% in Saharan Africa to 2% to 4% in Northern Europe, Southeast Asia, and Caribbean countries. Approximately 10% of Mediterranean countries and 5-20% of United States patients are seropositive for HHV-8.[12][13] This unique predilection for sub-Saharan African, the Mediterranean, and South America is unique to HHV-8 amongst human herpesviruses.[14]

AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma is the second most common tumor in HIV patients with CD4 counts less than 200 cells/mm3 and is an AIDs-defining illness.[15] Up to 30% of HIV patients not taking high-activity antiretroviral therapy (HAART) will develop Kaposi sarcoma. HIV positive male homosexuals have a 5- to 10-fold increased the risk of Kaposi sarcoma.[16][6]

Iatrogenic Kaposi sarcoma has a male: female ratio of 3:1 [6]. Over 5% of transplant patients who develop a de novo malignancy will develop Kaposi sarcoma, a 400- to 500-fold increased risk over the general population.[17][18] Patients with bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplant have much lower risks of developing Kaposi sarcoma compared to solid organ transplant patients.[18][6]

Pathophysiology

HHV-8 is a double-stranded enveloped DNA virus with 6 major subtypes (A-F).[9]

Due to HHV-8 co-evolving with the human population for centuries, cofactors of immune defects and inflammation are required for the development of malignancy.[14] It is transmitted primarily via saliva in childhood and sexually, with some cases of infection via blood transfusion or intravenous drug use.[14] Seropositive family members will often infect other family members, particularly in areas where HHV-8 is endemic.[14][6]

After infecting endothelial cells, HHV-8 activates the mTOR pathway, alters the cells to have mesenchymal differentiation, and promotes aberrant angiogenesis [14]. Through immune suppression and inflammation, the HHV-8 infected cells can persist and proliferate. Expression of latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA) causes binding of p53 and suppression of apoptosis [14][19]. LANA also maintains the viral episome and prevents Fas-induced programmed cell death.[19] NF-kB is activated by HHV-8 and up-regulates cytokine expression. Up-regulation of VEGF and bFGF results in neo-angiogenesis [19]. It induces c-kit expression and produces the spindled morphology of Kaposi sarcoma cells from their original cuboidal monolayer.[19] Matrix metalloproteinases are upregulated by HHV-8.[19]

Interestingly, Kaposi sarcoma is not monoclonal and different nodules within a patient have different clonal origins.[14]

Clinically, Kaposi sarcoma is a vascular lesion, and as such, often presents as a violaceous pink to purple plaque on the skin or mucocutaneous surfaces. Lesions may be painful with associated lymphedema and secondary infection.[6][19] There are 3 major stages on the skin: patch, plaque, and nodule.[20] Lesions may ulcerate or invade into nearby tissues.[20] In addition to involving lymph nodes, Kaposi sarcoma has a predilection for the lungs and gastrointestinal system, but can also occur in other visceral organs.[20] Respiratory involvement can be associated with death due Kaposi sarcoma.[19]

Histopathology

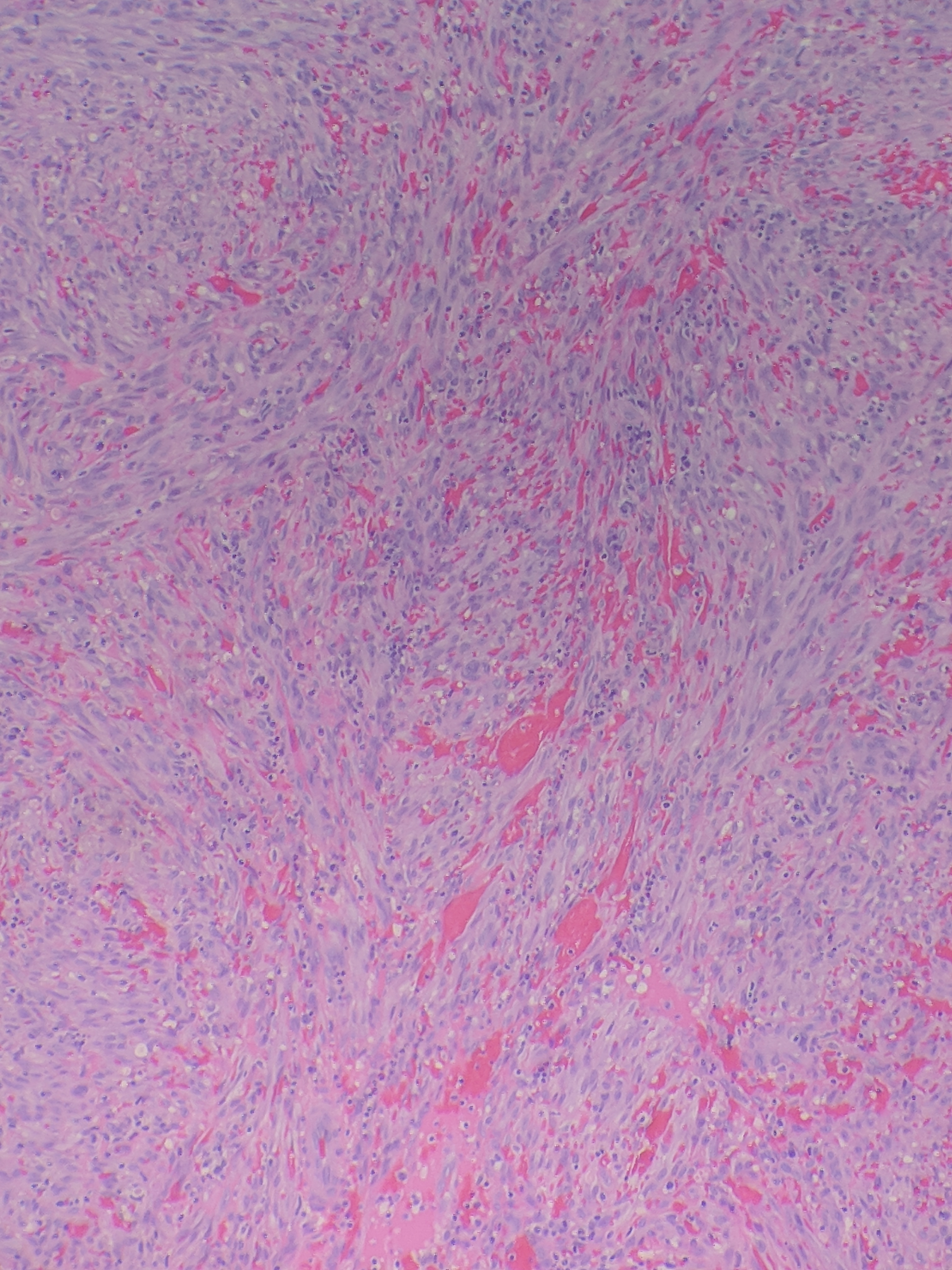

Kaposi sarcoma progresses through 3 distinct clinical stages: patch, plaque, and nodular.

The patch stage of Kaposi sarcoma is characterized by a spindle cell proliferation of irregular, complex vascular channels dissecting through the dermis with the promontory sign, defined as ramifying proliferating vessels surrounding larger ectatic pre-existing vessels and skin adnexa.[20][3] Extravasated red blood cells, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, rare hyaline globules, and perivascular lymphocytes and plasma cells are also frequently identified.

Advancement to the plaque stage of Kaposi sarcoma has an increasing prominence of the features seen in the patch stage with extension into the subcutis, and more prominence of the hyaline globules intra- and extra-cellularly.[20][3] These hyaline globules are periodic acid-Schiff positive and demonstrate Weibel-Palade bodies by electron microscopy.[20] Cellular pleomorphism is minimal, and there are few mitotic figures.[20][3]

As Kaposi sarcoma develops into the nodular form, the pleomorphism increases and mitotic figures become more prominent [3]. The slit-like lumens are enhanced as well.[20][3]

Histologic variants of Kaposi sarcoma include: in situ Kaposi sarcoma, anaplastic Kaposi sarcoma, lymphangiectatic Kaposi sarcoma, bullous Kaposi sarcoma, ecchymotic Kaposi sarcoma, glomeruloid Kaposi sarcoma, and hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma.[20]

The presence of HHV-8 can be confirmed with immunohistochemistry for LANA1.[14]

History and Physical

A general history and physical are performed first. The skin is examined for purplish lesions or lymph node enlargement that may signal the presence of Kaposi sarcoma. Suspicious lesions on the skin or lymph nodes can be biopsied and sent to pathology for evaluation. Particular care and attention should be paid to mucocutaneous surfaces as it is a common presenting location.

Evaluation

For a definitive diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma, they must perform a biopsy or excision of the suspicious areas. A pathologist examines the tissue under the microscope and looks for the characteristic features: a spindle cell vascular proliferation in the dermis.[20][3] Immunohistochemistry positivity for LANA1 (a surrogate marker for HHV-8) helps to differentiate Kaposi sarcoma from similar lesions. The lesional cells also express CD34, factor VIII, PECAM-1, D2-40, VEGFR-3, and BCL-2.[20]

Treatment / Management

Skin involvement of Kaposi sarcoma is treated by local excision, liquid nitrogen, and injection of vincristine.[19][6] Chemotherapy is a mainstay of treatment for endemic and systemic forms, in particular in children.[6][9]

Patients with HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma respond well to HAART,[21][22] which can cause regression or complete treatment of their sarcoma. In patients with severe Kaposi sarcoma, combines HAART with chemotherapy.[23] Iatrogenic Kaposi sarcoma treatment must balance a reduction in immune suppression or withdrawal of steroid treatment with transplant rejection and treatment of the sarcoma.[9]

Differential Diagnosis

Histologically, spindle cell vascular lesions in the skin include a differential diagnosis of[20][3]:

- Interstitial granuloma annulare

- Spindle cell hemangioma

- Acquired tufted angioma

- Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma

- Cutaneous angiosarcoma

- Fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

- Aneurysmal dermatofibroma

- Acroangiodermatitis

- Spindle cell melanoma

- High-grade sarcomas

The differential diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma on mucocutaneous surfaces includes[6]:

- Nevi

- Pyogenic granuloma

- Bacillary angiomatosis

- Hemangioma

- Angiosarcoma

- Melanoma

Radiation Oncology

Classical Kaposi sarcoma tends to be radiosensitive, especially in early stages of the disease. Dosages recommended are 15.2 Gy for oral lesions, 20 Gy for conjunctiva, eyelids, lips, hands, feet, penis, and anal regions, and 30 Gy with hypofractionation for other parts of the body.[21] For later stages of Kaposi sarcoma, radiation treatment may be used palliatively to reduce pain, edema, and bleeding.[21]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Thalidomide, VEGF inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and matrix metalloproteinases are currently under investigation as single agents to treat Kaposi sarcoma.[6][24] Several studies are currently ongoing for new and novel treatment for Kaposi sarcoma, including[25]:

- Intra-lesional nivolumab for cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma

- Pomalidomide with liposomal doxorubicin for refractory Kaposi sarcoma

- Pembrolizumab for relapsed and refractory HIV related neoplasms

- Ipilimumab and nivolumab for advanced HIV related neoplasms

- Nelfinavir for endemic, classic, and HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma

- Valganciclovir for HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma, particularly patients with immune reconstitution syndrome

- Recombinant EphB4-HAS fusion protein

- Selumetinib

Medical Oncology

High-activity antiretroviral therapy (HAART) is the mainstay of treatment in patients with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma. Not only does HAART treatment reduce the risk of development of Kaposi sarcoma, but it also can lead to spontaneous regression of the tumors.[21][22]

For local disease, sclerotherapy, intralesional vinca-alkaloids, bleomycin, interferon-alpha, topical alitretinoin, or imiquimod cream have all been used with success.[6]

Systemic chemotherapy approved for treatment of Kaposi sarcoma includes liposomal anthracyclins, paclitaxel, etoposide, vincristine, vinblastine, vinorelbine, bleomycin, or a combination of doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine.[19][6] Others have used interferon-alpha 2b with success.[6] Other therapies tried to include thalidomide, VEGF inhibitors, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and matrix metalloproteinases but further research into these as single agents is still being conducted.[6][24]

Staging

Kaposi sarcoma is not usually staged, however, a staging system was initially developed in the 1980s for HIV-related Kaposi sarcoma by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group.[26][13] With modern HAART, there are 2 proposed risk categories: good and poor.[26] Poor prognosis was based on poor tumor stage and poor systemic disease status.[26]

Prognosis

Ten percent to 20% of patients with the classic form of Kaposi sarcoma will succumb from their disease, but another larger percentage will develop a secondary malignancy that may also be lethal.[3] Endemic, HIV-related, and iatrogenic forms of Kaposi sarcoma have a variable prognosis. Prognosis may depend on CD4 count and opportunistic infections. In patients with iatrogenic Kaposi sarcoma, the prognosis is dependent on their underlying condition and their ability to tolerate a reduction in immunosuppression.[3] Worse prognosis is usually found in patients with visceral organ involvement, particularly the lungs.[3][19]

Complications

Larger lesions can be painful and lead to edema and disfigurement of the skin. Pulmonary involvement of Kaposi sarcoma can cause respiratory distress and lead to death. Classic Kaposi sarcoma has a known association with the development of a secondary malignancy.

Chemotherapy is not without side effects, including but not limited to neurotoxicity, infertility, cardiac toxicity, and nerve pain.

Radiation therapy can lead to drying of the skin, avascularity, poor healing, development of additional malignancies, and lymphedema.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients should be followed closely for resolution or recurrence of their disease.

Pearls and Other Issues

- There are 4 major forms of Kaposi sarcoma: classic, endemic, HIV-related, and iatrogenic, each with a different patient population and presentation.

- All cases of Kaposi sarcoma harbor the HHV-8 virus, though this is not sufficient to cause the neoplasm.

- Histologically, Kaposi sarcoma presents as a spindle cell vascular neoplasm with extravasated red blood cells and hyaline globules.

- Immunohistochemistry for LANA-1 can confirm the presence of HHV-8 in the neoplastic cells.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Kaposi sarcoma has been definitively linked to HHV-8 infection with increased incidence in patients with HIV infection, immunosuppression, or of Eastern European or Mediterranean descent. In seropositive patients at high risk of development of Kaposi sarcoma, the primary care team should take care to perform thorough skin exams looking for the characteristic violaceous patches and plaques. Additionally, patients in these high-risk groups should be counseled to examine their skin as well for lesions. Discovery of any suspicious lesions should prompt expedient biopsy and examination by a pathologist. Patient care is enhanced by the submitting provider providing a complete clinical history and mentioning the suspicion for Kaposi sarcoma to the reviewing pathologist.

Patients who are diagnosed with Kaposi sarcoma should be closely monitored for disease regression or recurrence and need for radiation treatment or systemic chemotherapy. If the HIV-associated or iatrogenic form, the clinical team should communicate and work closely to begin HAART or help reduce the immunosuppression while treating the patients underlying condition. (Level I)

Dentists and oral health care providers should be educated about the clinical presentation in the oral cavity as this a common location.