Continuing Education Activity

Much of the hand's inherent functionality can be attributed to a delicate balance between the intrinsic and extrinsic musculature. Injury to or compromise of the intrinsic musculature can lead to the development of an intrinsic minus (claw) or intrinsic plus (contracture) hand. If left untreated, these deformities may cause profound functional limitations, including digital and wrist stiffness, impaired grip strength, an inability to grip objects properly, and challenges with personal hygiene. A thorough history and physical examination are typically sufficient to diagnose intrinsic hand deformity. Additional imaging, laboratory tests, and neurological studies may be indicated to establish an underlying etiology. While nonoperative management, such as bracing, therapy, and injections, may be adequate interventions in milder cases, more advanced deformities may require operative treatment.

This activity for healthcare professionals reviews the etiologies, pathophysiological processes, common clinical presentations, evaluation, and management of intrinsic hand deformities. The role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with these potentially debilitating conditions is emphasized.

Objectives:

Identify the pathophysiology of intrinsic hand deformities.

Apply best practices when evaluating patients with an intrinsic hand deformity.

Determine the best management options for patients with intrinsic hand deformities.

Communicate strategies to promote collaboration among the interdisciplinary team to improve care delivery for patients with intrinsic hand deformities.

Introduction

The hand's functionality significantly depends on the balance of intrinsic and extrinsic musculature. Compromise of the intrinsic musculature can lead to the development of characteristic deformities—intrinsic minus (claw) or intrinsic plus (contracture) hands. If left untreated, these deformities may cause profound functional limitations, including digital and wrist stiffness, diminished strength, dysfunctional grip, challenges with personal hygiene, and others.[1][2][3]

Intrinsic Anatomy

The intrinsic muscles are those structures with both an origin and insertion within the hand. These include the thenar eminence muscles, hypothenar eminence muscles, lumbricals, and interossei.

Thenar eminence muscles

- Flexor pollicis brevis

- Abductor pollicis brevis

- Adductor pollicis

- Opponens pollicis

Hypothenar eminence muscles

- Flexor digiti minimi brevis

- Abductor digiti minimi

- Palmaris brevis

- Opponens digiti minimi

Lumbricals

Interossei

The lumbricals and interossei collectively assist in flexing the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and extending the interphalangeal joints (IPJ). Additionally, the dorsal interossei aid in abducting, while the volar interossei facilitate adducting the digits.

Innervation

Innervation of the intrinsic musculature is primarily supplied by the ulnar nerve. The following muscles are innervated by the median nerve:

- Flexor pollicis brevis

- Abductor pollicis brevis

- Opponens pollicis

- First and second lumbricals

Extrinsic Anatomy

The extrinsic muscles originate at the radius, ulna, or humerus but insert within the hand. These include various extensors of the wrist (eg, extensor carpi radialis longus/brevis, extensor carpi ulnaris) and digits (eg, extensor digitorum communis, extensor pollicis longus), and many flexors of the wrist (eg, flexor carpi radialis, flexor carpi ulnaris) and digits (eg, flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor digitorum profundus).

Etiology

The etiology determines the presentation of an intrinsic minus (claw) or intrinsic plus (contracture) hand.

Intrinsic Minus (Claw) Hand

Intrinsic minus (claw) hand can be caused by trauma to the ulnar or median nerves, compartment syndrome of the hand, or Charcot-Marie Tooth disease. Other potential etiologies are classified by the nerve that is affected.

- Ulnar nerve palsy: a compressive neuropathy of the ulnar nerve at Guyon's canal (ulnar tunnel syndrome) or the medial elbow's cubital tunnel (cubital tunnel syndrome).

- Median nerve palsy: caused by leprosy (Hansen disease), Volkmann ischemic contracture, or pronator syndrome.

Intrinsic Plus (Contracture) Hand

Trauma can lead to the development of an intrinsic plus (contracture) hand.[4][5] Direct trauma includes metacarpal or phalangeal fractures, burns, and crush injuries. Indirect trauma associated with immobilization can lead to further damage caused by adhesion formation and fibrosis of the intrinsic muscles and tendons. Ischemia of the muscles can also cause fibrotic changes. Neurologic causes such as cerebrovascular accident, cerebral palsy, and traumatic brain injury leading to upper motor neuron syndromes can cause upper extremity spasticity and intrinsic tightness. Moreover, rheumatoid arthritis has been implicated in intrinsic contractures due to muscle spasms, adhesions, and decreased range of motion. In congenital cases, arthrogryposis may manifest as hand or wrist contractures.

Epidemiology

Trauma is the most common cause of intrinsic deformities of the hand and is more prevalent in men than women. Nerve trauma may be isolated to the ulnar or median nerves. Approximately 22% of nerve injuries involving the volar forearm are combined injuries to both the ulnar and median nerves.[6] Additionally, one-third of patients with rheumatoid arthritis develop an intrinsic contracture, and 20% to 25% of patients with leprosy develop peripheral nerve palsies that can result in an intrinsic minus hand deformity.[7][8]

Pathophysiology

Intrinsic Minus (Claw) Hand

The intrinsic minus hand usually occurs due to an imbalance between functional extrinsic and dysfunctional intrinsic musculature. Impaired function of intrinsic musculature leads to loss of MCP flexion and interphalangeal extension. This results in unopposed extension of the MCP joints by the extrinsics and unopposed flexion of the IPJ by the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus tendons. Pathophysiological processes vary depending upon specific nerve involvement.

Ulnar nerve-mediated

Ulnar nerve injury or dysfunction is the leading cause of intrinsic muscle palsy. Ulnar nerve injuries are differentiated into 2 categories: low and high.[9] Low ulnar nerve injuries are those distal to the motor branch of the flexor carpi ulnaris and flexor digitorum profundus. The sensation of the volar aspect of the 4th and 5th fingers is impaired. The sensation of the dorsal aspect of these fingers is also lost if the injury occurs proximal to the dorsal ulnar sensory nerve. Motor paralysis affects all interosseous muscles, including the 2 ulnar lumbricals, hypothenar muscles, adductor pollicis, and the deep head of flexor pollicis brevis.

As discussed, loss of intrinsic muscle contraction results in impaired active MCP joint flexion and IPJ extension, leading to MCP hyperextension and IPJ flexion of the ring and little fingers (Duchenne sign). This posture is known as the intrinsic minus or claw hand. It has also been referred to as the Benediction sign, which is more evident when the patient is asked to extend the fingers (see Image. Benediction Hand).[10][11] The development of this position requires functioning flexor and extensor extrinsic muscles. For this reason, high ulnar injuries that affect the ulnar half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle result in less severe deformity.[12]

Intrinsic weakness leads to a 60% to 80% loss of pinch and grip strength. Performing a pinch of the thumb pulp to the index finger pulp leads to excessive flexor pollicis longus contraction, causing excessive thumb IPJ flexion due to weakness of the adductor pollicis (Froment sign). Thumb MCP joint hyperextension may also develop if there is MCP joint laxity (Jeanne sign). The index finger may also present with proximal IPJ hyperflexion greater than 90° due to first dorsal interosseous muscle weakness (Mannerfelt sign).[13][14] (See Images. Froment Sign and and Jeanne Sign.)

Another dysfunctional hand posture caused by interosseous weakness is the Andre-Thomas sign. To compensate for the lack of active MCP extension, the wrist is flexed to increase tension on the extensor digitorum communis to extend the MCP joints. However, this posture increases MCP extension and ultimately worsens the deformity.[15] Finger abduction (dorsal interossei), and adduction (volar interossei) are lost (see Image. Wartenberg Sign). Second and third dorsal interosseous palsy leads to impaired abduction of the middle finger (Pitres-Testut sign/Egawa sign) when the palm is placed flat on a table. In more severe cases, atrophy of the interosseous and hypothenar muscles and a flattened palmar metacarpal arch (Masse sign) develop. Third palmar interosseous palsy causes the fifth finger to be abducted due to unopposed extensor digiti minimi pull, making abduction difficult (Wartenberg sign).

Median nerve-mediated

Median nerve injuries are also differentiated into 2 categories: high and low. High median nerve deficits affect the volar extrinsic muscles, resulting in a supination and ulnar deviation posture of the hand. Paralysis of the median nerve-innervated intrinsics leads to weak flexion of the MCP joints as the ulnar-innervated interosseous muscles act alone. The index finger, middle finger, and thumb's IPJ cannot flex due to paralysis of the flexor digitorum profundus/superficialis and flexor pollicis longus. Thumb opposition is also impaired, and the thumb lies in the same plane as the metacarpals because of the paralysis of the abductor pollicis brevis and opponens pollicis. This characteristic posture is also known as the Benediction sign, which is exacerbated when the patient attempts to make a fist.[16] Atrophy of the thenar eminence develops in severe cases. Low median nerve injuries generally don't affect extrinsic muscle function. Thus, when the patient is asked to make a fist, the index and middle fingers lag behind the ring and little fingers due to a lack of flexion at the MCP joints. The thumb also lies in the plane of the palm, as its opposition is impaired.

Intrinsic Plus (Contracture) Hand

The intrinsic plus hand most commonly occurs due to spasticity or contracture of the intrinsic muscles, leading to flexion of the MCP joints and extension of the IPJ. However, it can also occur due to extrinsic muscle weakness. In those cases, extensor digitorum communis and flexor digitorum profundus/superficialis weakness do not provide the balancing extension and flexion forces, respectively, to the MCP and IPJs.

History and Physical

The evaluation of patients with intrinsic hand deformity begins with history-taking. The patient often reports diminished hand function, such as grip weakness, difficulty grasping objects, and digital deformity. It is important to gather information regarding symptom onset, the mechanism of injury, and any associated neurological deficits. Past medical and surgical history should be reviewed to determine if the patient has previously dealt with compressive neuropathies. Inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis, should be noted.

Clinical examination is often used to establish the diagnosis of an intrinsic hand deformity. Special attention should be given to range of motion, hand posture, and signs of muscle atrophy, including characteristic examination findings.

Intrinsic Minus (Claw) Hand

Posture: In a typical claw hand, the MCP joints are hyperextended, while the IPJs are flexed. With an ulnar nerve-mediated pathology, the ring and little fingers will have a more severe deformity due to the innervation of their lumbricals by the ulnar nerve. Conversely, if the claw hand is due to a median nerve-mediated pathology, the index and middle fingers will be more affected, as their lumbricals are innervated by the median nerve.

Motor testing: Grip and pinch strength testing with a dynamometer reveals decreased strength compared to the contralateral upper extremity, and the patient may be unable to perform a prehensile grasp. A more systematic evaluation of the motor function of the intrinsics of the hand can be performed as follows, and should be performed bilaterally.

- The first dorsal interosseous is assessed by placing the ulnar side of the patient's hand on the examination table. The patient is asked to abduct the index finger while the examiner applies resistance.

- The second to fourth dorsal interossei are evaluated by instructing the patient to abduct all fingers against resistance.

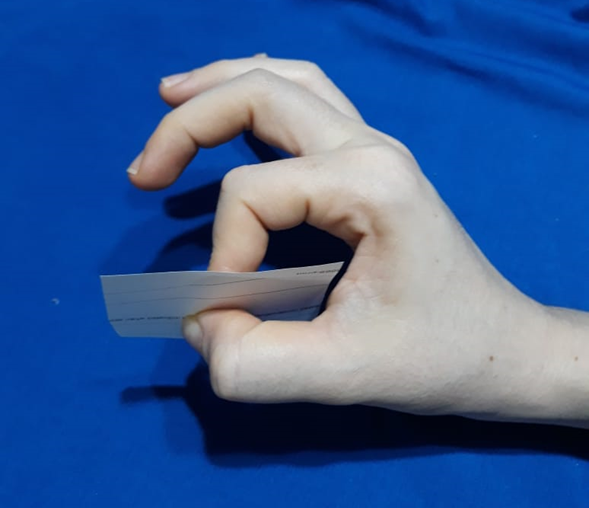

- Volar interossei are tested by placing a sheet of paper between the extended and adducted fingers and asking the patient to hold the paper while the examiner attempts to pull it away.

- The abductor digiti minimi is assessed by instructing the patient to abduct the little finger against resistance.

- The flexor digiti minimi brevis is evaluated by flexing the MCP joint with the IPJs in extension while the examiner resists at the base of the proximal IPJs.

- The opponens digiti minimi is tested by asking the patient to perform a pulp-to-pulp pinch with the thumb.

- The abductor pollicis brevis is assessed by instructing the patient to abduct the thumb against resistance.

- The opponens pollicis is evaluated by thumb opposition to the little finger.

- The adductor pollicis is tested by asking the patient to pinch a sheet of paper between the thumb and index finger.

- The flexor pollicis brevis is assessed by thumb MCP flexion against resistance.

Sensation testing: Light touch and two-point discrimination should be performed to assess for sensory deficits.

Provocative testing: In an intrinsic minus hand, the IPJ flexion deformity will correct (extend) if the corresponding MCP joints are brought out of hyperextension.

Intrinsic Plus (Contracture) Hand

In addition to performing the motor and sensory examination as detailed above for the intrinsic minus hand, the following findings are typically observed with an intrinsic plus hand.

Posture: An intrinsic plus hand is characterized by MCP flexion and IPJ extension. Affected patients may also present with a swan neck deformity, diminished inter-digital spacing, and an adducted thumb.[5]

Active and passive range of motion should be assessed to differentiate between muscle contractures (characteristic of the intrinsic plus hand) and joint contractures (which may occur due to other pathology or disuse). It is also important to consider the presence of lateral band adhesions, which can result in limited IPJ flexion and extension of the MCP joint.

Provocative testing: The "intrinsic tightness test," first described by Sterling Bunnell in 1948, distinguishes between intrinsic and extrinsic tightness.[17] When there is normal muscle tone and an adequate balance between the intrinsic and extrinsic musculature, the examiner can passively extend the patient's MCP joints and simultaneously passively flex the proximal IPJ without any resistance or limitation in movement. With intrinsic tightness, the force required to flex the proximal IPJs is greater when the MCP joint is passively extended versus flexed. This occurs because the intrinsic muscles are volar to the axis of rotation of the MCP joint and dorsal to the axis of the proximal IPJ. Thus, MCP joint hyperextension tightens the intrinsic muscles. Conversely, when the force required for IPJ flexion increases while flexing the MCP joint, this indicates an extrinsic contracture.

Evaluation

Intrinsic hand deformities are usually diagnosed clinically, but additional studies are available when clinical evaluation is inconclusive. Radiographs (postero-anterior, oblique, and lateral views) can show the presence of osseous deformities or articular instability contributing to hand deformity. Lacerations, stretch injuries, and contusions of the ulnar or medial nerve are the most common mechanisms of injury underlying an intrinsic minus hand deformity.[12] It is critical to determine whether surgical intervention is required. Neuropraxia and axonotmesis can be managed without surgery, but neurotmesis does require operative treatment.[18]

Electrodiagnostic tests such as electromyography and nerve conduction velocity studies can help determine the level of injury. However, findings will depend upon the chronicity of the injury. Although it is generally taught that electrodiagnostic studies should not be performed until 3 to 4 weeks after the injury (to allow for Wallerian degeneration), potentially valuable information can be obtained from early studies. Studies performed in the first week help determine the location of the injury. One to 2 weeks after injury, whether the lesion is complete or incomplete can be determined. At 3 to 4 weeks post-injury, it is possible to differentiate axonotmesis or neurotmesis from neuropraxia. At 3 to 4 months post-injury, signs of reinnervation are perceptible. High-resolution ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also accurately identify nerve discontinuity, the presence of neuromas, or the development of perilesional scar tissue.[19][20]

Treatment / Management

Intrinsic hand deformities have many causes, so treatment approaches are varied. Proper treatment depends on understanding the etiology. The following discussion represents some, but not all, of these options.

Intrinsic Minus (Claw) Hand

Treatment of intrinsic palsy causing claw hand posture must prioritize recovering motor function when the potential exists. In this case, a hand therapist will oversee a treatment program consisting of passive and active stretching exercises and the fabrication of an anti-claw splint. This splint positions the MCP joints in slight flexion to prevent hyperextension, facilitating IPJ extension by the intact extrinsic musculature.

Surgical intervention may be necessary in cases affecting the patient's quality of life. An acute ulnar or median nerve laceration requires immediate surgical evaluation and treatment. Surgical intervention can be delayed 3 to 7 days following injury if the wound is contaminated. Prolonged delays increase the risk of requiring nerve grafting, fibrosis of the stump, and neuronal loss.[21] As an alternative or augmentation to recover intrinsic function, distal nerve transfers, such as an anterior interosseous nerve transfer to the ulnar motor branch, have been used with good functional recovery reported.[22]

Surgical approaches to treating the chronic intrinsic minus hand involve releasing contractures with active tendon transfers or passive tenodesis. The Bouvier test is a clinical maneuver that can help guide the treatment plan by classifying the claw hand deformity as simple or complex.[23] When passive correction of the MCP hyperextension allows the patient to extend the IPJs through the intact extensor mechanism (positive Bouvier test), the claw deformity is classified as a simple claw hand. However, when the patient cannot actively extend the IPJs after passive MCP hyperextension correction, extensor mechanism impairment exists (negative Bouvier test), and deformity is classified as a complex claw hand (see Image. Claw Hand).

In patients with simple clawing, tendon transfers are performed to restrict MCP joint hyperextension. The Zancolli lasso technique involves dividing the flexor digitorum superficialis of the affected digits at its insertion into 2 slips, each of which is then passed around the corresponding A1 or A2 pulley and sutured back onto itself.[23] Volar plate capsulodesis with transosseous fixation can also be performed and augmented with internal bracing, particularly if the flexor digitorum profundus is not functional.[24]

For complex clawing, active IPJ extension should also be achieved in addition to correcting MCP hyperextension. The modified Brand transfer is an active tendon transfer that involves dividing the extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon into 4 distinct tails, each of which is grafted to the lateral bands to restore intrinsic-like function. Other active tendon transfer procedures, including a modified Stiles-Bunnell transfer and the Fowler procedure, are available.[25][26]

Intrinsic Plus (Contracture) Hand

The treatment of intrinsic contractures is guided by etiology and severity. In mild cases, hand therapy in the form of passive stretching and bracing is the first-line treatment.

As with intrinsic minus deformities, surgical intervention for intrinsic contractures is reserved for functionally debilitating deformities. These procedures may include:

- Proximal intrinsic release is indicated when intrinsic muscles have become fibrotic and are no longer functional. Releasing the transverse and oblique fibers of the intrinsic mechanism proximal to the MCP joint reduces tension on the intrinsic musculature, thereby improving mobility.

- Distal intrinsic release is used to treat more severe tightness involving both the MCP and IPJs or for intrinsics that have become fibrotic. The goal is to decrease the tension on the IPJs without affecting the MCP joint. It consists of resecting the intrinsic tendon distal to the transverse fibers (distal to the MCP joint). When MCP joint flexion contractures are present, distal intrinsic releases alone are inadequate. Therapeutic alternatives include proximal intrinsic release, intrinsic muscle slide, botulinum toxin type-A injections, and ulnar nerve motor branch neurectomy.

- Proximal muscle slide is indicated in less severe cases involving spasticity. It involves subperiosteal elevation of the intrinsic muscles, which allows the interosseous muscles to slide distally while the MCP joints are extended.

- Ulnar neurectomy is indicated in cases with spasticity; however, it is ineffective if a fixed contracture of the MCP joint is present.[4]

Tendon Transfers for Pinch

Tendons that can be used to restore thumb opposition function include the extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor digiti minimi, flexor digitorum superficialis, extensor indicis proprius, and brachioradialis. One available technique is the transfer of the extensor carpi radialis brevis, which is lengthened with a palmaris longus autograft, passed through the second intermetacarpal space, and then sutured to the adductor pollicis insertion.[27] Additionally, the flexor digitorum superficialis of the ring finger can be divided near its insertion and routed around the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon at the wrist and then sutured to the radial aspect of the thumb MCP joint. First dorsal interosseous transfers involve use of the extensor indicis proprius or the abductor pollicis longus to stabilize the index finger during pinch.

Differential Diagnosis

Specific conditions that should be considered when evaluating a patient with a hand deformity include:

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Dupuytren contracture

- Parsonage-Turner syndrome

- Brachial plexus neuritis (lower brachial plexopathy)

- Pronator syndrome

- Forearm Volkmann contracture

- Locked trigger fingers

- Metacarpal or phalangeal malunions.

Prognosis

Lower energy injuries, younger patients, and acute nerve lacerations undergoing primary repair have a better prognosis for recovery. Conversely, high-energy injuries, older patients, and chronic neuropathies associated with muscle atrophy have a poorer prognosis. A flexible claw hand has a better prognosis if a procedure aimed at preventing MCP hyperextension is performed. Many treatments for these conditions have fair outcomes, and significant improvement in hand function may take several years following surgery.

Complications

If left untreated, mild claw hand deformities can progress and affect multiple digits. Long-term tightness of the intrinsic muscles results in decreased MCP extension and swan neck deformities.[3] These complications lead to further impaired hand function and disability with both gross and fine motor tasks.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Various postoperative therapy and rehabilitation protocols exist. The content of these protocols varies depending on the underlying pathology and the specific procedure performed.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Given the potentially debilitating nature of intrinsic hand deformities, patient education and deterrence efforts should focus on seeking prompt medical care following trauma that results in any impairment of hand function. This may contribute to improved quality of life for patients and help prevent clinically-significant negative outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach is essential to achieve the best outcomes in treating intrinsic hand deformities. The team may consist of orthopedic nurses, radiologists, primary care clinicians, pain specialists, neurologists, orthopedic surgeons/hand surgeons, emergency medicine clinicians, and hand therapists. Primary care and emergency medicine clinicians may be the first to encounter a patient with an intrinsic hand deformity, which should prompt coordination with an orthopedist/hand surgeon for expeditious evaluation. Neurologists may be consulted to perform electrodiagnostic studies to contribute to the diagnosis. Nurses and therapists play an important role in ensuring therapy adherence. A comprehensive care coordination strategy should be implemented to maximize patient outcomes.