Continuing Education Activity

Intertrochanteric femur fractures are a very common injury seen in the elderly. Understanding the pathophysiology as well as the proper treatment options will significantly decrease the risk of mortality and morbidity of this injury. This activity reviews the evaluation and treatment of intertrochanteric femur fractures and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and treating patients with this condition.

Objectives:

- Describe the most common mechanisms of injury that can result in intertrochanteric femur fractures.

- Summarize the diagnostic approach for an evaluation and assessment of a patient presenting with a potential intertrochanteric femur fracture, including any indicated imaging studies and potential differentials.

- Outline the treatment options for intertrochanteric femur fractures, depending on patient population and fracture severity and location.

- Outline interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination and communication to improve outcomes with intertrochanteric femur fracture treatment.

Introduction

Intertrochanteric fractures are defined as extracapsular fractures of the proximal femur that occur between the greater and lesser trochanter. The intertrochanteric aspect of the femur is located between the greater and lesser trochanters and is composed of dense trabecular bone. The greater trochanter serves as an insertion site for the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, obturator internus, piriformis, and site of origin for the vastus lateralis. The lesser trochanter serves as an insertion site for the iliacus and psoas major, commonly referred to as the iliopsoas. The calcar femorale is the vertical wall of dense bone that extends from the posteromedial aspect of the femur shaft to the posterior portion of the femoral neck. This structure is important because it determines whether or not a fracture is stable. The vast metaphyseal region has a more abundant blood supply, contributing to a higher union rate and less osteonecrosis compared to femoral neck fractures.[1][2]

Etiology

These fractures occur both in the elderly and the young, but they are more common in the elderly population with osteoporosis due to a low energy mechanism. The female to male ration is between 2:1 and 8:1. These patients are also typically older than patients who suffer femoral neck fractures. In the younger population, these fractures typically result from a high-energy mechanism.[3]

Epidemiology

These fractures along with other hip fractures are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Currently, 280,000 fractures occur annually with nearly half of these due to intertrochanteric fractures. By 2040, it is estimated to increase 500,000.[4]

Pathophysiology

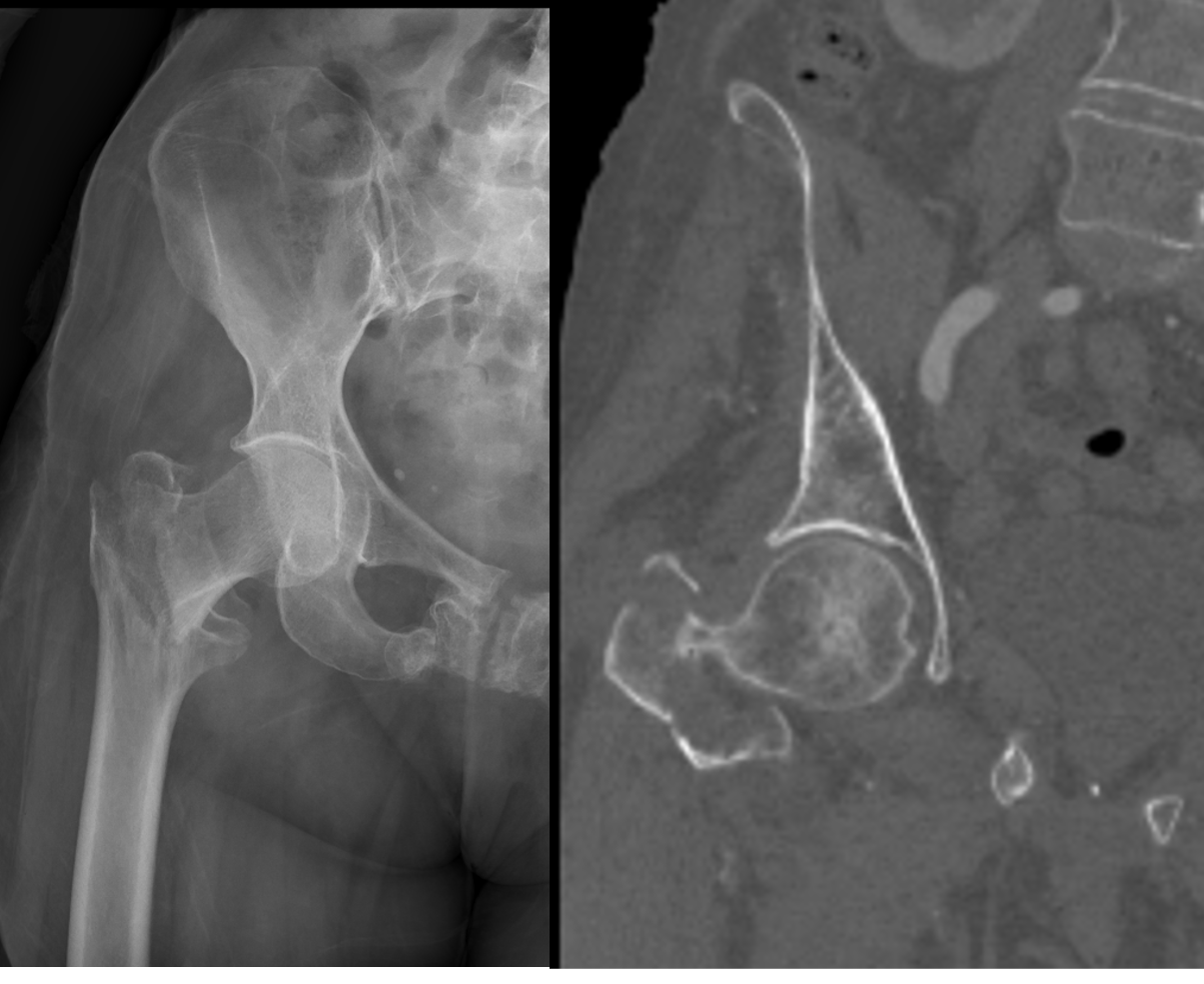

These fractures are usually a result of a ground-level fall in the elderly population and are classified as either stable or unstable. Determination of stability is important as it helps determine the type of fixation required for stability. Stable fractures have an intact posteromedial cortex and will resist compressive loads once reduced. Examples of unstable fractures include: comminution of the posteromedial cortex, a thin lateral wall, displaced lesser trochanter fracture, subtrochanteric extension and reverse obliquity fractures. This Evans classification breaks down intertrochanteric femur fractures based on displacement, number of fragments and the type of fragment displaced. Type I is a 2 part fracture, Type II are 3 part fractures and Type III are 4 part fractures. The A subclassification in type I fractures is used for non displaced fractures while B fractures are displaced. In type II fractures, the A subclassification describes a 3 part fracture with a separate GREATER trochanter fragment while the B subclassification describes a 3 part fracture with a LESSER trochanter fragment. Type III fractures are 4 part fractures.

History and Physical

These patients typically present with a short and externally rotated lower extremity. Past medical and social history should be obtained to optimize perioperative management and to prepare for postoperative rehabilitative care. It is important to evaluate the skin (open versus closed fracture) and the neurovascular status. Evaluation of a range of motion is typically not possible due to pain. Basic lab studies such as complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and coagulation studies should be obtained to recognize abnormalities that may need time to correct prior to surgical stabilization. Early involvement of an interprofessional team including anesthesia and internal medicine or geriatrics is ideal to medically optimize surgical candidates for operative repair.

Evaluation

Plain radiographs are the initial films chosen to evaluate for these fractures. The recommended views include the anteroposterior (AP) pelvis, AP and cross-table lateral of the affected hip and full-length radiographs of the affected femur. Although the diagnosis can be made without pelvic films, pelvic radiographs are useful to assist in preoperative planning for restoration of the proper neck-shaft angle. Full-length radiographs of the femur are useful to assess for deformities of the femur shaft which could affect the placement of an intramedullary nail and evaluation of prior implants in the distal femur. CT and MRI are typically not indicated but can be used if radiographs are negative, although the physical exam is consistent with a fracture. MRI is indicated if there is an isolated greater trochanteric femur fracture and intertrochanteric extension is of concern. Additionally, a physician-assisted AP traction view of the injured hip can be helpful in further characterizing fracture morphology and feasibility of closed reduction or need for open reduction techniques.[5][6]

Treatment / Management

[2]Nonoperative treatment is rarely indicated and should only be considered for non-ambulatory patients and patients with a high risk of perioperative mortality or those pursuing comfort care measures. The outcomes of this method of treatment are poor due to an increased risk of pneumonia, urinary tract infection, decubiti, and deep vein thrombosis.[7][1]

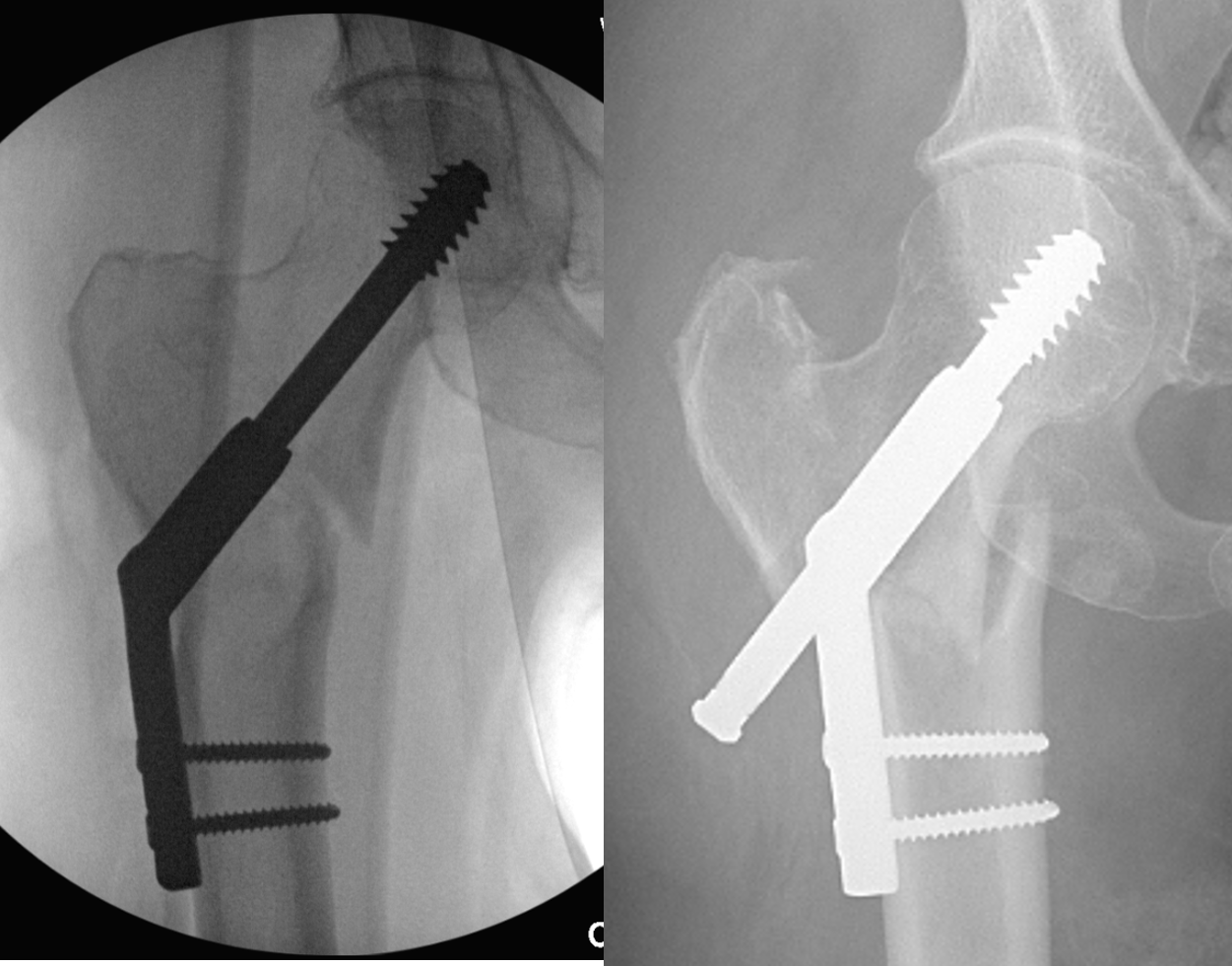

The type of surgical treatment is based on the fracture pattern and its inherent stability, as the failure rate is highly correlated with the choice of implant and fracture pattern. Fractures with involvement of the lateral femoral wall are considered an indication for intramedullary nailing and would not be treated with a sliding hip screw. Unstable fracture patterns such as fractures with comminution of the posteromedial cortex, a thin lateral wall, displaced lesser trochanter fractures, subtrochanteric extension of the fracture and reverse obliquity fractures are also indications for intramedullary nailing.

Operative management of these fractures is considered urgent, not emergent. This allows the many comorbidities with which patients often present to be optimized preoperatively, to reduce morbidity and mortality. Most of these fractures are treated operatively with either a sliding hip screw or intramedullary hip screw, although arthroplasty is a rare option. Indications for the sliding hip screw include stable fracture patterns with an intact lateral wall. When used for the appropriate fracture pattern, this treatment affords outcomes similar to intramedullary nailing. The advantages of the dynamic hip screw are that they allow for dynamic interfragmentary compression and are low cost compared to intramedullary devices. The main disadvantages include increased blood loss and open technique. Implant failure can occur due to a lack of integrity of the lateral wall or the placement of the screw, which should be placed at a tip apex distance of less than 25 millimeters.

Intramedullary nailing can be used to treat a broader range of intertrochanteric fractures, including the more unstable patterns such as reverse obliquity pattern. One proposed advantage of the intramedullary hip screw is its minimally invasive approach which minimizes blood loss. Although there are is no data suggesting that an intramedullary hip screw is more effective than a sliding hip screw in treating stable fracture patterns, it is becoming more and more commonly used by young surgeons. The choice for short or long intramedullary implants is debatable in these fractures.

Arthroplasty is typically not indicated as primary management and is reserved for severely comminuted fractures, patients with a history of degenerative arthritis, salvage of internal fixation, and osteoporotic bone that is unlikely to hold internal fixation.

Differential Diagnosis

Extracapsular

- Intertrochanteric femur fracture

- Trochanteric femur fracture

Proximal

- Intracapsular

- Femoral head fracture

- Femoral neck fracture

Shaft

Complications

Regardless of treatment choice, there remains a 20% to 30% mortality risk in the first year following fracture, with males having a higher mortality rate compared to females. In patients who are treated nonoperatively, cardiopulmonary, thromboembolic events and sepsis are the most common complications seen.[8]

Operative complications include blood loss anemia, infection, nonunion, and collapse, among others. One of the more recognized complications of implant-related failure is screw cutout, which is usually caused when the cephalomedullary screw is placed at a tip apex distance greater than 25 millimeters. If this occurs, a corrective osteotomy with open revision reduction and internal fixation is usually needed in the young patient, whereas in the elderly, treatment for this complication is typically conversion to hip arthroplasty. Another recognized complication with the placement of a long intramedullary device in the elderly population is anterior perforation of the distal femur cortex. This is the result of a mismatch of the radius of curvature of the femur and the implant. The incidence of nonunion is low, less than 2%.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The postoperative protocol consists of weight-bearing as tolerated, chemical VTE prophylaxis for up to 6 weeks, and progressive physical therapy beginning in the immediate postoperative period.[9]

Consultations

A multidisciplinary care team is most effective for the comprehensive treatment of these patients, both pre- and postoperatively. This includes early involvement of geriatric or internal medicine, anesthesia, orthopedics, and any other subspecialty service needed, depending on the patient's comorbidities.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated regarding the overall morbidity and mortality of their injury, including the challenges they will face when returning to pre-injury function. They should be encouraged that active participation in therapy plans will play a significant role in preventing morbidity and mortality and regaining mobility.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The majority of patients with intertrochanteric fractures present to the emergency room. Besides the triage nurse, the nurses on the orthopedic floor should be aware of this fracture and its management. Because many of these patients are initially at bed rest, prophylaxis for deep vein thrombosis is vital.

The main concern of intertrochanteric fractures is the 20% to 30% mortality risk in the first year following fracture, with males having a higher mortality rate compared to females. If the fracture is not operatively treated within two days of injury, mortality risk increases. Other factors increasing mortality include age greater than 85 years, two or more pre-existing medical conditions, ASA classification (ASA III and IV increases mortality). Early medical optimization and co-management with medical hospitalists or geriatricians can improve outcomes. The most predictive factor of functional outcomes following operative treatment is a pre-injury function, age, and dementia. With stable fracture patterns, more than half of patients will regain pre-injury walking function and pre-fracture level of activity of daily living function. Unstable fracture patterns tend to have worse outcomes when compared to the stable fracture patterns, with most patients experiencing a decline in mobility. Immediate postoperative management is imperative as older adults with these fractures have a five- to eight-time increase in risk for all causes of mortality during the 90-day postoperative period.[10][11]