Continuing Education Activity

In the past, the term cholangiocarcinoma was used to reference intrahepatic bile duct cancer. However, usage of the term has evolved and it is now used to reference intrahepatic, perihilar, and extrahepatic tumors of the bile tract such as hepatobiliary tract cancer. The gallbladder and ampulla of Vater are considered structures of the biliary tract system hence malignancies of those parts are usually included in research and publications involving cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma remains a rare and highly lethal malignancy due to the characteristically locally advanced, unresectable stage upon diagnosis. This activity reviews the evaluation, treatment, and prognosis of hepatobiliary tract cancer and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in evaluating and improving care for patients with this condition.

Objectives:

Describe the population most at risk for developing hepatobiliary tract cancer.

Explain exam findings that should prompt consideration of hepatobiliary tract cancer.

Review the evaluation of hepatobiliary tract cancer.

Demonstrate interprofessional team strategies for improving care coordination to enhance outcomes for patients affected by hepatobiliary tract cancer.

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma originally referred to intrahepatic bile duct cancer. However, the term currently includes intrahepatic, perihilar, and extrahepatic tumors of the bile tract such as hepatobiliary tract cancer. The gallbladder and ampulla of Vater are considered structures of the biliary tract system hence malignancies of those parts are usually included in research and publications involving cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma is a rare and highly lethal malignancy due to the locally advanced, unresectable stage at diagnosis. [1][2]

Etiology

Chronic inflammation is associated with the risk of developing biliary tract cancer. The strongest correlation to develop cholangiocarcinoma is primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a feature characteristic of inflammatory bowel disease, particularly ulcerative colitis. In addition, choledochal cyst, hepatolithiasis, and liver fluke are well-known risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma. Other associations for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma are chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), metabolic syndrome, and alcoholic and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Thorotrast, a radiological contrast, was banned due to its carcinogenic potential with a strong association with cholangiocarcinoma. Cholangiocarcinoma has been described with Lynch syndrome and multiple biliary papillomatosis.[3]

Epidemiology

Although cholangiocarcinoma represents 3% of all gastrointestinal malignancies, the United States Cancer Statistics estimate 52,450 new cases and 32,750 expected death cases by grouping liver, intrahepatic bile duct, gallbladder, and other biliary cancer. Collectively, this represents 6% of all new cancer sites, making it the fifth deadliest cancer. Intrahepatic, perihilar, and distal biliary tract cancers divided by anatomical site account for 5% to 10%, 50% to 60%, and 20% to 30% of cases, respectively. Cholangiocarcinoma incidence increases with age except in cases related to primary sclerosing cholangitis which manifests in younger patients and is slightly more common in males, excluding gallbladder cancer which has a female predominance.[4]

Pathophysiology

The current hypothesis establishes that chronic inflammation of the bile duct tissue will accumulate successive genomic mutations that over the years will lead to malignant transformation similar to other gastrointestinal cancers. Intraductal papillary neoplasm and intraepithelial neoplasia are well-known cholangiocarcinoma precursors, which may progress from pre-neoplastic to carcinoma in situ and then into invasive cancer while progressively harboring mutations in p53, SMAD4, CDK2A tumor suppressors and/or oncogenes RAS, BRAF, EGFR, and PIK3CA. Cholangiocarcinoma histopathology is adenocarcinoma in more than 90% of cases and, infrequently, squamous cell carcinoma. Intrahepatic carcinomas also may have a biphenotypic differentiation called hepatocholangiocarcinoma. [5]

Histopathology

Histologically, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma usually consists of penetrating well-formed or cribriform glands in an ample fibrous stroma

History and Physical

Bile duct obstruction symptoms include jaundice; abdominal pain, particularly in the right upper quadrant; clay-colored stools; cola-colored urine; and skin pruritus which are common presentations of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Patients can present with unspecific symptoms of advanced malignancy including fever, night sweats, weight loss, and general malaise. Acute cholangitis is a rare presentation. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma may present differently with a more obscure scenario, such as an abnormal laboratory finding or a lesion detected incidentally on imaging in an otherwise asymptomatic patient during hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) screening for liver disease.

Physical examination may demonstrate jaundice, right upper quadrant pain, hepatomegaly, or Courvoisier sign with a palpable non-tender gallbladder which is more likely to develop due to a chronic progressive malignant obstruction rather than an intermittent benign obstruction.[6][7]

Evaluation

Patients, particularly those with obstructive jaundice or right upper quadrant pain, will require complete blood count, basic chemistry panel, and liver function tests. Results may reveal an initial, unspecific cholestatic pattern caused by bile obstruction that may lead to hepatocellular injury.

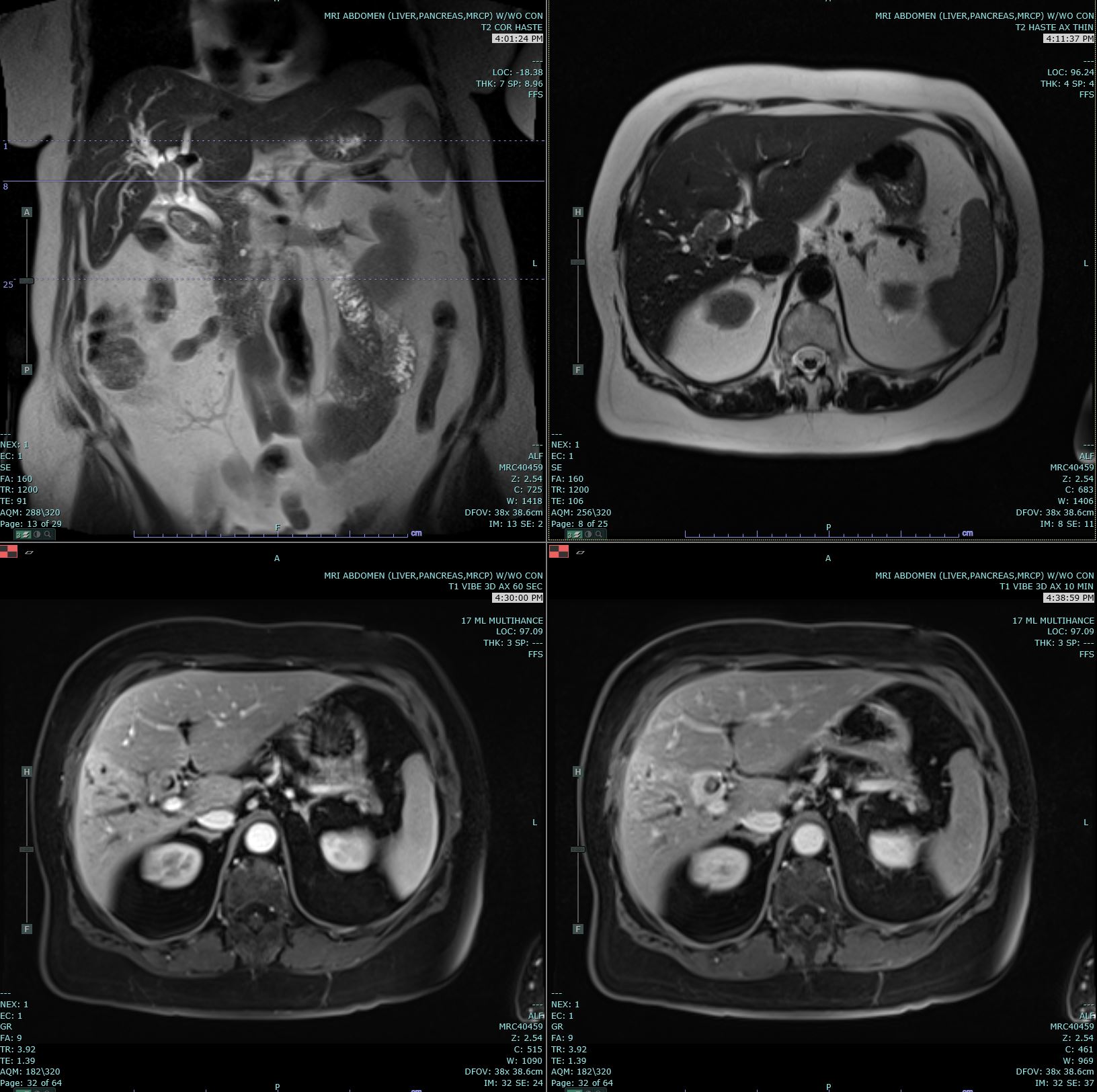

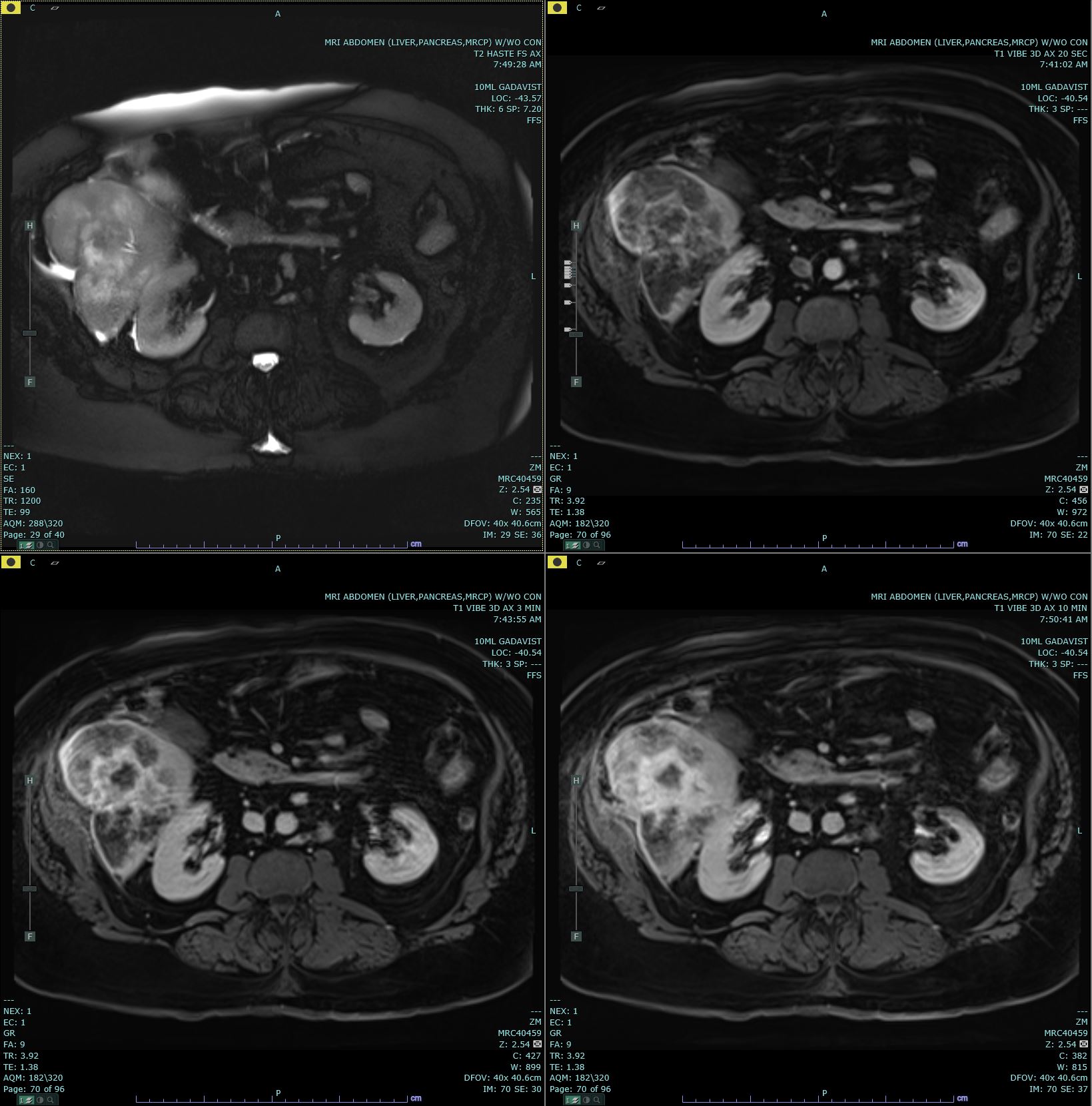

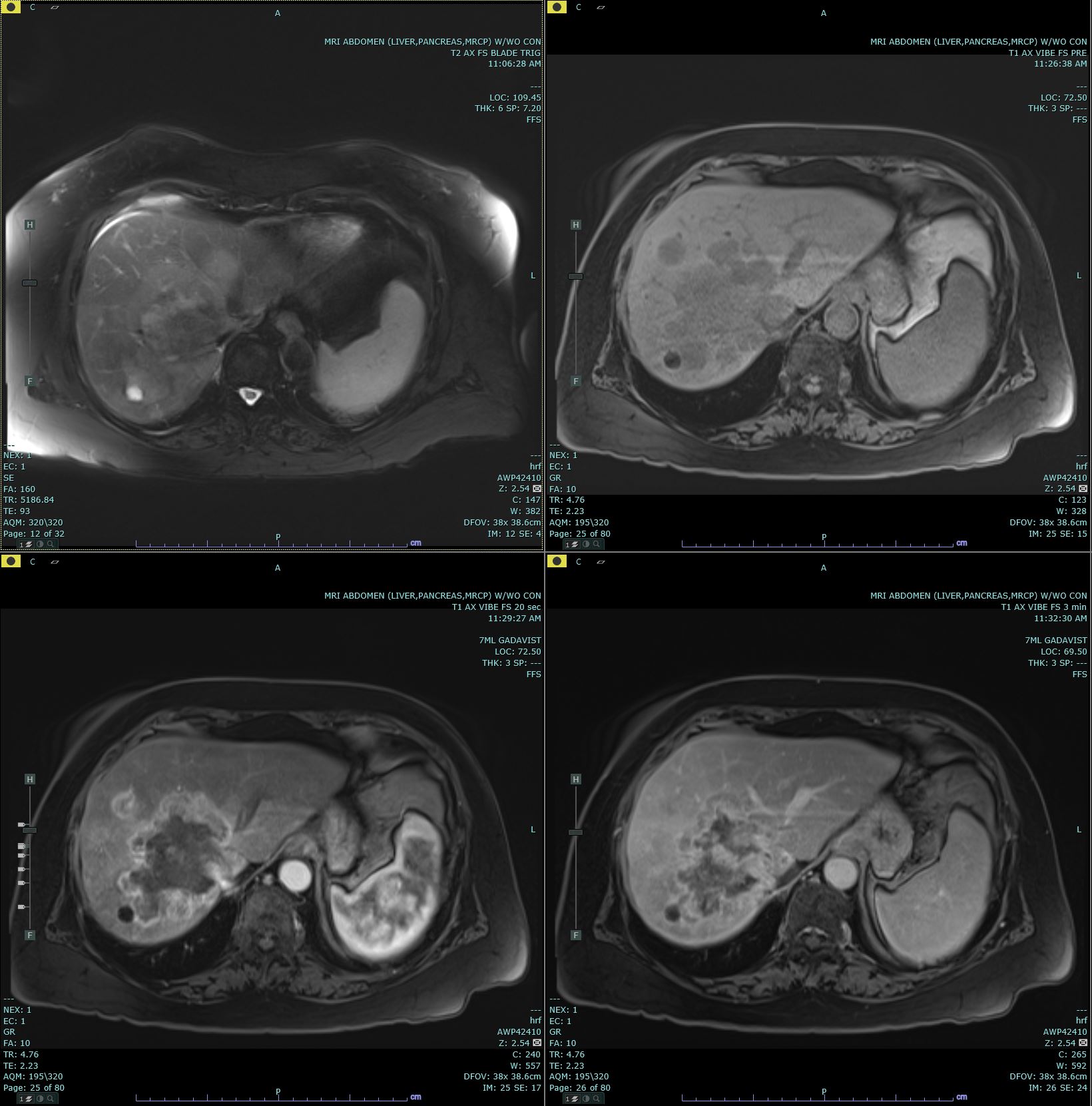

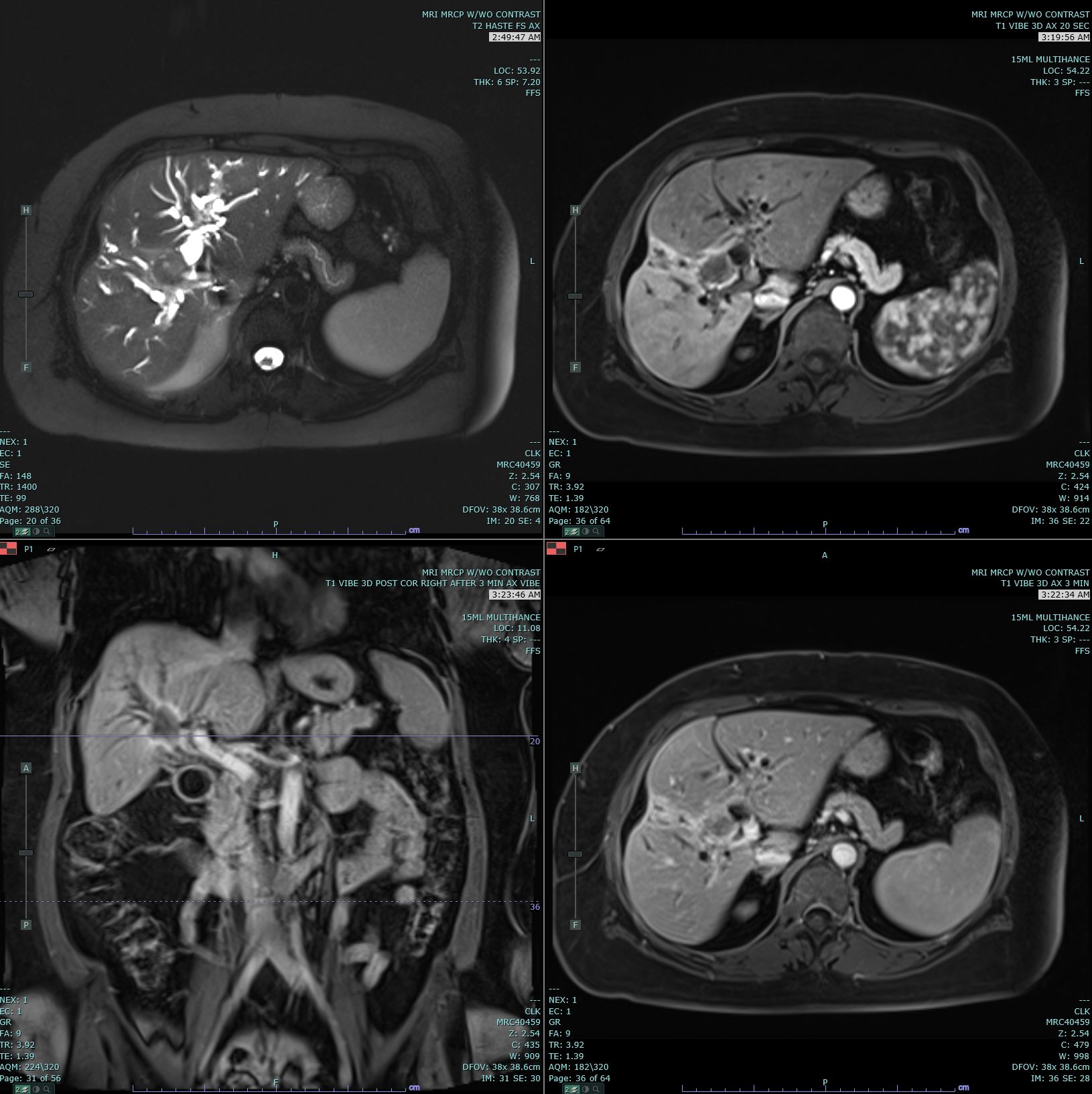

Ultrasonography (US) and CT are the usual initial imaging for jaundiced patients and provide information on the location and anatomy of the lesion. CT scans performed for intrahepatic lesions have limitations in discriminating benign from malignant lesions, but dynamic magnetic resonance (MR) and MR cholangiopancreatography can provide the disease extent more accurately and better distinguish intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma from hepatocellular carcinoma and biphenotypic carcinomas. Obtaining either intrahepatic or perihilar tissue for diagnosis may be challenging. Endoscopic ultrasound or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography are preferred modalities for extrahepatic obstruction because it allows direct bile duct visualization, diagnostic biopsy, and therapeutic interventions such as stent placement. Primary sclerosing cholangitis-associated cholangiocarcinoma can be challenging.

Tumor markers including carcinoembryonic antigen, alpha-fetoprotein, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 are frequently collected to differentiate suspicious intrahepatic lesions. Elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) may support hepatocellular carcinoma particularly those with liver disease and CA 19-9 for cholangiocarcinoma in the appropriate clinical scenario. Biphenotypic carcinomas may show AFP elevation. Ca 19-9 greater than 129 unit/mL, CEA greater than 5.2 ng/mL, and low IgG4 can support a cholangiocarcinoma diagnosis, particularly in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. A tumor markers baseline test is potentially useful for therapy monitoring and surveillance for recurrence of the disease. CA 19-9 on concentrations of hundreds of units/mL are consistent with advanced disease and poor prognosis.

Initial staging workup may include CT chest, abdomen, and pelvis if not previously obtained. If no metastatic disease is evident and the patient is being considered for surgical resection, occasionally positron emission tomography/CT can be ordered to evaluate for an occult disease which can prevent a morbid surgery. Surgical candidates will proceed with diagnostic laparoscopy before resection.

An American Joint Committee on Cancer and Union for International Cancer Control 2017 group separated the staging systems of cholangiocarcinoma depending on whether the location of the bile duct cancer is perihilar, distal, or intrahepatic. Each was differentiated on tumor size (T) designation and 5-year overall survival prognosis accordingly. On a multi-institutional analysis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, the 5-year survival rate was higher for those patients without multiple tumors or vascular invasion and nodal disease on surgical pathology specimen evaluation. [8][9][10]

Treatment / Management

Neoadjuvant therapy is not considered a standard of care in cholangiocarcinoma. Rarely, locally advanced or borderline resectable cases may receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy based on low-powered studies. Orthotopic liver transplantation has been studied in selected populations with inconclusive results. Neoadjuvant therapy should be offered in a clinical trial setting.

Surgery is the only curative treatment for selected patients. The surgical procedure differs according to the anatomical location. Distal lesions are treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy, the Whipple procedure. Intrahepatic lesions will require hepatectomy, and lymphadenectomy is rarely performed. For hilar lesions, surgical resection will vary according to the Bismuth-Corlette anatomical classification.

Type I Bismuth-Corlette can involve the extrahepatic bile ducts but not the biliary confluence and can be treated with biliary surgical resection/Whipple procedure. Type II involves an En bloc resection of the extrahepatic bile ducts, cholecystectomy, and hepatoduodenal ligament lymph node resection, with the creation of a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Type III (Type a and b) involves radical resection of the extrahepatic duct, with ipsilateral hepatic lobectomy, hepatoduodenal ligament lymph node resection, and a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy (Type III a require right hepatectomy or trisegmentectomy and Type IIIb requires a left hepatectomy). Type IV is predominately unresectable.[11]

Postoperative therapy should be offered within 8 to 12 weeks and requires baseline laboratory and imaging before therapy initiation.

Adjuvant therapy should be offered to patients with a resected pathological specimen and a report of vascular invasion, node positivity, and positive margins, and preferably, concurrent adjuvant chemoradiation or adjuvant chemotherapy alone should be offered. There is limited clinical trial data to define the standard of care, and enrollment in a clinical trial is encouraged.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) consensus-based adjuvant guidelines recommend the following[12]:

Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma with Negative Margins and Negative Nodes

Chemotherapy alone for 6 months with gemcitabine (Gem) [1000 mg/m2 weekly for 3 of every 4 weeks] or fluoropyrimidine (5-FU) [leucovorin 20 mg/m2 followed by FU 425 mg/m2 intravenous [IV] bolus days 1 through 5, every 28 days] published in the ESPAC-3 Trial which enrolled 96 patients with bile duct cancer, and the median overall survival (mOS) for the chemotherapy group was 43.1 months versus 35.2 months in the observation group, albeit not statistically significant. Alternatively, 5-FU [225 mg/m2 daily]-based adjuvant chemoradiation from other gastrointestinal malignancy extrapolation data from the rectal cancer experience. [13]

Extrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma with Positive Margins, Invasive Disease, or Carcinoma in Situ at the Margin

Four cycles of Capecitabine (Cap) [1500 mg/m(2) per day on days 1 to 14] plus Gemcitabine (Gem) [1000 mg/m(2) intravenously on days 1 and 8], every 21 days followed by 5-FU CRT [Cap 1330 mg/m2 per day divided into two daily doses and RT 45 Gy to regional lymphatics; 54 to 59.4 Gy to tumor bed] published in a single-arm SWOG-S0809 trial enrolled 54 bile duct cancer and showed a mOS of 35 months without a comparison group.

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma with Negative Disease

No recommendations.

Positive Margins

Consider re-resection, ablation, 5-FU or Gemcitabine chemotherapy, or chemoradiation therapy discussion with a multidisciplinary team.

At ASCO 2017, BILCAP study was presented as first phase 3 randomized adjuvant therapy for patients with no postsurgical complications and Eastern Cooperative Oncological Group of two or less (ECOG less than 2), 447 patients were randomized 1:1 Cap N 223[1250 mg/m2 D1-14, every 21 days, for eight cycles] or observation (Obs) N224 from 44 UK sites 2006 through 2014, it included 19% Intrahepatic, 28% hilar, 35% extrahepatic bile duct cancer and results showed an mOS for Cap 53mo when compared to Obs 36mo (HR 0.75 p0.028). Cap soon will be adopted as the new standard of care.

Surveillance by NCCN recommendations includes imaging every 6 months for 2 years if clinically indicated, then annually up to 5 years. The oncologist may monitor patients closely with liver function tests and tumor markers (CEA and CA19-9) every 3 to 4 months for 2 years, then every 6 months up to 5 years. All above-mentioned tests can be performed when clinically indicated.

No single or combined therapy in unresectable, locally advanced, and metastatic cholangiocarcinoma will achieve a cure; rather the focus is on palliative intervention and extension of survival. All patients with advanced and unresectable disease should be offered a clinical trial when feasible. Patients with good performance status (ECOG 0-1) for chemotherapy could consider first-line option Gem [1000 mg/m2] plus Cisplatin (Cis) [25 mg/m2] on days one and eight every three weeks with acceptable toxicity in low dose cis as published in ABC-02 randomized phase 2 study which included 242 metastatic bile duct cancer patients and showed a mOS of 11.7 months in the combination arm when compared to 8.3 months of Gem alone (HR, 0.70; p0.002). Other first-line, gem-based combinations are not randomized studies and have reported a mOS for GemCap 12.7 months and Gem with Oxaliplatin 14.3 months both on a selected population of patients. Alternative 5-FU-based combination plus Cis 11.5 months or Cap 11.3 months. Patients with poor performance may receive oral Cap which reported a mOS of 8.1 months when compared to the best supportive care of 4.5 months. Future clinical trials with targeted therapy, including FGFR, MEK, and other drugs tailored per the tumor molecular profile, are ongoing and preliminary reports are promising. [14][15]

Differential Diagnosis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Secondary sclerosing cholangitis

- Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis

- AIDS-associated cholangiopathy

- Autoimmune pancreatitis-cholangitis syndrome

- Hepatobiliary inflammatory pseudotumor

- Mirizzi Syndrome

- Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis or cholangitis

- Biliary sarcoidosis

- Chemotherapy-induced biliary sclerosis

- Intrabiliary metastasis

Surgical Oncology

Surgery is the only curative treatment for selected patients. The surgical procedure differs according to the anatomical location. Distal lesions are treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy, the Whipple procedure. Intrahepatic lesions will require hepatectomy, and lymphadenectomy is rarely performed. For hilar lesions, surgical resection will vary according to the Bismuth-Corlette anatomical classification.

Radiation Oncology

The addition of radiotherapy has been associated with an improvement in survival rate in older patients with nonmetastatic biliary tract tumors. Several studies showed that there was an increase in the median survival duration in patients undergoing radiation postoperatively

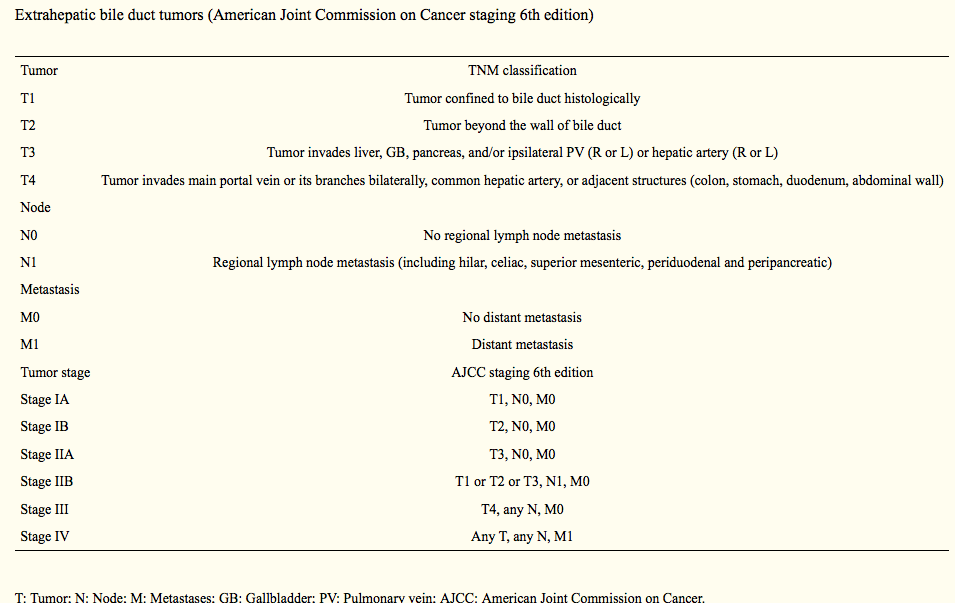

Staging

Staging follows the TNM system and is described in detail in table 1. For hilar lesions, staging for surgical resection will vary according to the Bismuth-Corlette anatomical classification.

Prognosis

Prognosis depends on the location of the tumor as well as the stage of the tumor

For intrahepatic bile duct tumors, the 5-year survival is as follows

- Localized tumor or stage I: 15%

- Regional spreading of the tumor seen in Stage II and III: 6%

- Distant metastasis or stage IV: 2%

For Extrahepatic bile duct tumors, the 5-year survival is as follows

- Localized tumor or stage I: 30%

- Regional spreading of the tumor seen in Stage II and III: 24%

- Distant metastasis or stage IV: 2%

Complications

Bile obstruction caused by the cancer can lead to infections , cholangitis , sepsis ,septic shock and death.

Other complication to keepin mind are the ones related to surgery , chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Biliary cancers have been associated with cirrhosis. Many causes of cirrhosis can be prevented such as excess alcohol intake, Infections with hepatitis B, and C among others. It is important to avoid the use of IV drug, excessive alcohol intake, and practice safe sexual relationships. A patient diagnosed with cancer should know that a multidisciplinary team involving multiple subspecialties is following the case. Keeping appointments, chemotherapy, radiotherapy sessions is crucial for a better outcome and survival.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bile duct carcinoma is very difficult to diagnose as it may present with similar symptoms to gallstones including obstructive symptoms such as jaundice; abdominal pain; clay-colored stools; cola-colored urine; and skin pruritus. Patients can also present with unspecific symptoms of advanced malignancy including fever, night sweats, weight loss, and general malaise. The healthcare team needs to be diligent in considering the possibility of this deadly form of cancer and always include it as a possibility when evaluating patients with presentations of gallbladder disease. an interprofessional team approach of nurses, pharmacists, and physicians will provide the best possible results. [Level V]