Continuing Education Activity

Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), formerly known as Hallervorden-Spatz disease, is a rare autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder associated with iron accumulation in the brain nuclei and characterized by progressive extrapyramidal dysfunction and dementia. Classically, the disease presents between ages 7 and 15 years. However, the disease onset has been reported in all age groups, including infancy and adulthood. As PKAN has an autosomal mode of inheritance, each sibling of an individual has a 25% chance of being affected and a 50% chance of being an asymptomatic carrier. This activity reviews the evaluation and management of pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration and highlights the role of the interprofessional team in the care of affected patients and their families.

Objectives:

Describe the pathophysiology of pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration.

Describe the typical presentation of a patient with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration.

Describe the risk of the affected child's mother having another child with pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration.

Describe the importance of improving care coordination amongst interprofessional team members to improve care for patients affected by pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration and to provide appropriate counsel to their families.

Introduction

Pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN), formerly known as Hallervorden-Spatz disease, is a rare autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder associated with iron accumulation in the brain nuclei and characterized by progressive extrapyramidal dysfunction and dementia.[1][2][3]

Etiology

PKAN was first described in 1922 by 2 German physicians, Hallervorden and Spatz, as a form of familial brain degeneration characterized by cerebral iron deposition. PKAN is a subset of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA), in the basal ganglia, with subsequent variable neurological dysfunction. Numerous genes (at least 10) have been identified, resulting in a variety of specific diseases.

The exact etiology of PKAN is not well understood. One of the proposed hypotheses is that aberrant oxidation of lipofuscin to neuromelanin and insufficient cysteine dioxygenase lead to abnormal iron accumulation in the brain. While portions of the globus pallidus and pars reticularis of substantia nigra have relatively higher iron content in healthy individuals, individuals with PKAN have excessive amounts of iron accumulated in these nuclei.

A role for mutation in the PANK2 gene (band 20p13) accounts for most inherited PKAN cases as the etiology of PKAN in various studies. Mutations result in an autosomal recessive inborn error of coenzyme A metabolism with a resultant deficiency of pantothenate kinase enzyme, which may lead to the accumulation of cysteine and cysteine-containing compounds in the basal ganglia. This causes chelation of iron in the globus pallidus and other basal ganglia and rapid auto-oxidation of cysteine in the presence of iron with subsequent free radical production. Pathologic examination reveals characteristic rust-brown discoloration of the globus pallidus and substantia nigra pars reticularis due to underlying iron deposition and a reduction in the size of these nuclei. Generalized atrophy of the brain parenchyma may be seen in severely advanced cases.[4][5]

Epidemiology

According to some studies prevalence of PKAN is 1-9/1000000. The classic presentation is in the late part of the first decade or the early part of the second decade, between ages 7 and 15 years. However, the disease onset has been reported in all age groups, including infancy and adulthood.

Pathophysiology

The mechanism by which basal ganglia iron uptake is increased in PKAN is unknown since systemic and cerebrospinal fluid iron levels, as well as plasma ferritin, transferrin, and ceruloplasmin, all are normal. One of the proposed mechanisms is that aberrant oxidation of lipofuscin to neuromelanin and insufficient cysteine dioxygenase leads to abnormal iron in the brain. While portions of the globus pallidus and pars reticularis of substantia nigra have high iron content in healthy individuals, individuals with PKAN have excess amounts of iron deposited in these nuclei. A role for mutation in the PANK2 gene (band 20p13) accounts for most inherited PKAN cases in the etiology of PKAN in various studies. Mutations result in an autosomal recessive inborn error of coenzyme A metabolism with a resultant deficiency of pantothenate kinase may lead to the accretion of cysteine and cysteine-containing compounds in the basal ganglia. This causes chelation of iron in the globus pallidus and rapid auto-oxidation of cysteine in the presence of iron with subsequent free radical generation.

Pathologic examination reveals characteristic rust-brown discoloration of the globus pallidus and substantia nigra pars reticularis due to iron deposition and a reduction in the size of the caudate nuclei, substantia nigra, and tegmentum, as well as generalized atrophy of the brain.

Microscopically marked neuroaxonal and myelin degeneration is a distinctive pathologic feature of PKAN.

- Ubiquitinated spheroids, which represent swollen axons with vacuolated cytoplasm inactivated by attachment of ubiquitin, are found most abundantly in the pallidonigral system and in the cerebral cortex.

- Accumulation of iron-containing pigment, mostly neuromelanin, and ceroid lipofuscin, in the palladonigral system

History and Physical

PKAN is characterized by progressive dystonia, a motor disorder of extrapyramidal type with gait difficulty. In classic form, usually, onset occurs in the first decade. Clinical manifestations of PKAN vary from patient to patient.

Patients with this disease suffer from a variety of other neurological symptoms and signs, including:

- Extrapyramidal symptoms: dystonia, dysarthria, muscular rigidity, spasms, Parkinson-like symptoms.

- Dystonia (continuous spasms and muscle contractions)- A prominent and early feature

- Tremors, rarely bradykinesia (slowness of movement) and Choreoathetosis(involuntary movements in along with chorea(irregular migrating contractions) and athetosis (twisting and writhing)

- Significant speech disturbances - Can occur early

- Dysphagia - A common symptom; caused by rigidity of muscles and associated corticobulbar abnormality

- Dementia - Present in most patients with PKAN

- Visual impairment - Consequence of optic atrophy or retinal degeneration; can be the presenting symptom of the disease, although this is rare

- Seizures - Have been reported frequently

- Akathesis- (feeling of internal motor restlessness that can present as tension, nervousness, or anxiety)

- Neuropsychiatric dysfunction

- Optic atrophy

- Retinal degeneration

Approximately 25% of individuals have an 'atypical' presentation with onset later in life (onset mostly in a second and third decade), delay of extrapyramidal dysfunction for several years, and more gradual progression of the disease process. Prominent speech defects, spasticity, and psychiatric disturbances also dominate in the atypical form.

Based on the common clinical features, the following diagnostic criteria have been proposed. For a definitive diagnosis, all of the obligate findings and, at minimum, two of the corroborative findings should be present.

Obligate features of PKAN are the following:

- Onset in the first two decades of life

- Progression of signs and symptoms; classic form: loss of ambulation occurring within 10-15 years of onset; atypical form: ambulatory loss occurs within 15-40 years of disease onset.

- Evidence of extrapyramidal dysfunction, including one or more of these neurological impairments: dystonia, rigidity, and choreoathetosis.

Corroborative features are listed as follows:

- Corticospinal tract involvement: spasticity, hyperreflexia, and extensor toe signs

- Progressive intellectual deterioration

- Retinitis pigmentosa and/or optic atrophy( seen with electroretinogram or visual field testing)

- Seizures

- Family history consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance( may include consanguinity)

- Hypointense areas on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the involved basal ganglia

- Abnormal cytosomes in circulating lymphocytes

- Red blood cell acanthocytosis

Evaluation

CT Imaging

CT is not very helpful in the diagnosis of PKAN, but rarely hypodensity in the basal ganglia, and some atrophy of the brain has been reported. Calcification in the basal ganglia in the absence of any atrophy has also been described.

Brain MRI

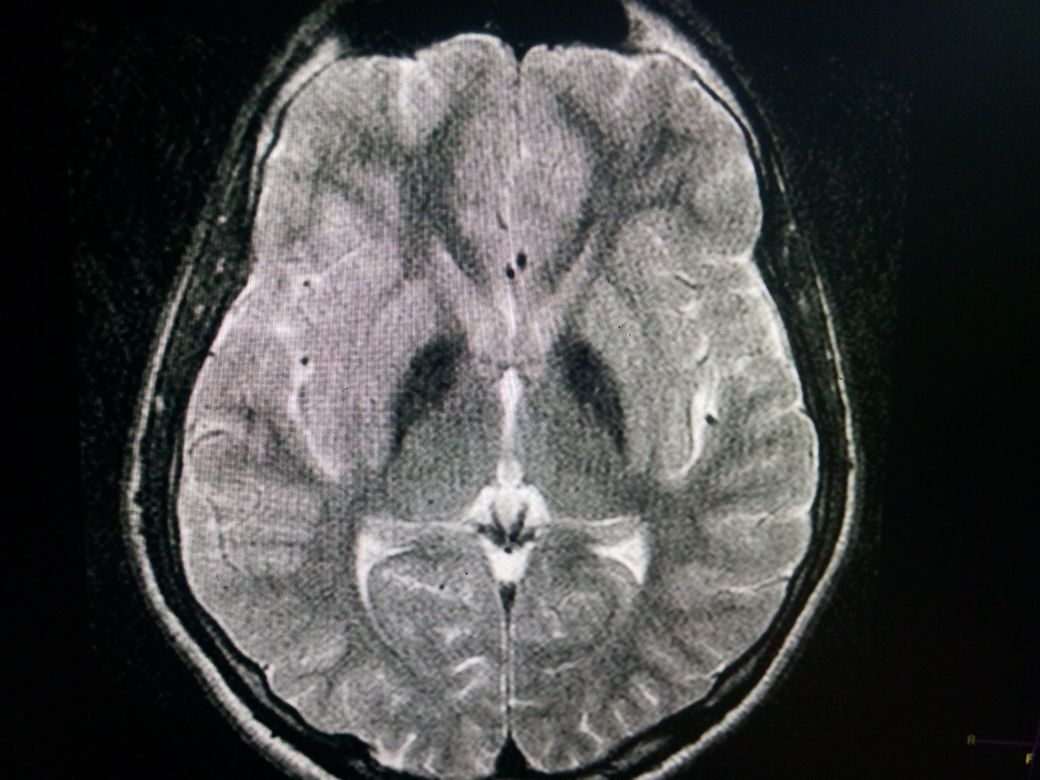

Brain MRI the standard in the diagnostic evaluation of all forms of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). NBIA has significantly increased the likelihood of a diagnosis of PKAN. Imaging findings are most conspicuous on T2W sequences which demonstrate hypointensity reflecting areas of iron deposition, mainly in globi pallidi, pars reticulata of the substantia nigra, and red nuclei. Studies report that all patients with PANK2 mutations, whether classic or atypical, have the characteristic radiologic sign known as the "eye of the tiger" on brain MRI, which is evident as bilateral symmetrical, central foci of hyperintense signals in the anteromedial globus pallidus, with a surrounding zone of hypointensity in the globus pallidus on T2W MR scanning. The central T2 relatively hyperintense spot or line within the globi pallidi is due to gliosis and vacuolization. This sign was not reported in patients without PANK2 mutations. The cortex is usually spared, but atrophy can be seen in advanced cases.

SWI/T2*

Show susceptibility artifact (blooming low signal) in corresponding areas due to iron accretion. MR spectroscopy shows decreased NAA peak due to neuronal loss and may depict increased myoinositol.

SPECT Scanning

Iodine-123 ( I)-beta-carbomethoxy-3beta-(4-fluorophenyl) tropane SPECT scanning and ( I)-iodobenzamide (IBZM)-SPECT scanning have been used in making the diagnosis of Hellervorden Spatz disease but are not commonly used in the clinical setup.

Antenatal Diagnosis

Prenatal testing for pregnancies at risk is through DNA testing. Cells are usually obtained by amniocentesis at 15 to 20 weeks of gestation or by chorionic villus sampling at 10 to 13 weeks. At least one mutation in the proband of extracted DNA should be present for a prenatal diagnosis of NBIA. If both pathogenic variants have been found in an affected family member, carrier testing for at-risk relatives is possible by the same technique.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of patients with Hellervorden Spatz disease or PKAN is mostly symptomatic. The tremors best respond to dopaminergic agents. For rigidity and spasticity, dopamine agonists and anticholinergic agents alone or in combination may be used. Intrathecal or oral Baclofen in moderate doses relieves stiffness and spasms and can reduce dystonia. Intramuscular botulinum toxin has also been used for the alleviation of hypertonicity. Benzodiazepines have been used for choreoathetotic movements. Medications such as methscopolamine bromide can be attempted for excessive drooling. Dysarthria could respond to medications employed for rigidity and spasticity. A multidisciplinary team approach, including physical and speech therapy, swallowing evaluation, dietary assessment, gastrostomy tube feeding, and computer-assisted devices, may be used in advanced cases to improve functional and communication skills.[6][7][8]

Dementia is gradual and progressive and usually does not respond to treatments. Affected individuals with recurrent tongue biting due to severe Oro buccolingual dystonia, bite blocks, and full-mouth dental extraction may be the only effective measure. The use of systemic chelating agents, such as desferrioxamine, has been attempted to remove excess iron from the brain, but it didn't prove beneficial. Research and trials for the administration of coenzyme A and high dosage of pantothenate are still in progress. However, no conclusive data are available.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses include the following:

- GM gangliosidoses

- Huntington disease

- Juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis

- Machado-Joseph disease

- Neuroacanthocytosis

- Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis

- Wilson disease

Pearls and Other Issues

As PKAN has an autosomal mode of inheritance, each sibling of an individual has a 25% chance of being affected, a 50% chance of being an asymptomatic carrier, and a 25% chance of being asymptomatic and not a carrier.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

PKAN is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes nurses, geneticists, and counselors. The disorder has no cure and is progressive. Genetic testing should be offered to the parents, and counseling provided. The prognosis for most patients is very poor.