Introduction

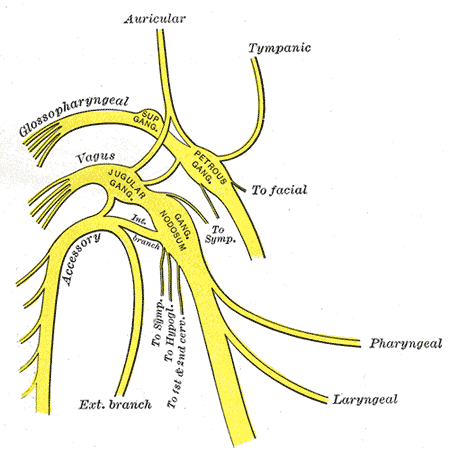

The glossopharyngeal nerve is the 9th cranial nerve (CN IX). It is 1 of the 4 cranial nerves with sensory, motor, and parasympathetic functions. It originates from the medulla oblongata and terminates in the pharynx. This nerve is most clinically relevant in glossopharyngeal neuralgia, but an injury to it can also be a complication of carotid endarterectomy (see Figure. The Glossopharyngeal Nerve).

Structure and Function

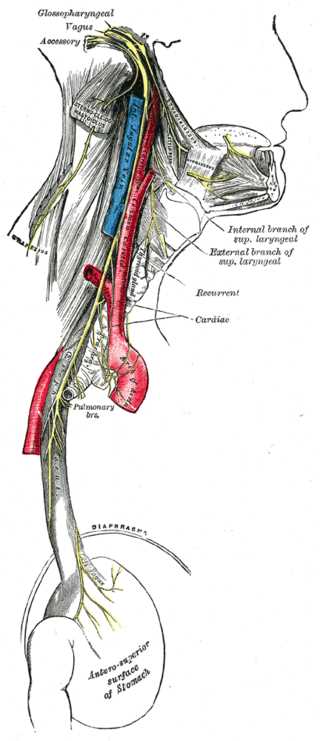

The glossopharyngeal nerve carries sensory, efferent motor, and parasympathetic fibers. Its branches consist of tympanic, tonsillar, stylopharyngeal, carotid sinus nerve, branches to the tongue, lingual branches, and a communicating branch to cranial nerve X (vagus nerve). See Image. The Glossopharyngeal Nerve. Special visceral efferent fibers (branchial motor) are the main motor fibers of the glossopharyngeal nerve and supply motor innervation to the stylopharyngeus muscle. This muscle elevates the larynx and pharynx, especially during speaking and swallowing. General visceral efferent fibers (visceral motor) provide parasympathetic innervation to the parotid glands. The fibers originate in the inferior salivary nucleus, travel with the tympanic nerve through the foramen ovale, and synapse at the otic ganglion. General visceral afferent fibers (visceral sensory) carry sensory information from the carotid sinus and body. General somatic afferent fibers (general sensory) provide sensory innervation to the upper pharynx, the inner surface of the tympanic membrane, and the posterior third of the tongue. Special sensory fibers also provide taste afferents from this portion of the tongue.[1]

Embryology

The glossopharyngeal nerve derives from the third pharyngeal arch and is the only structure formed by it, although the third pharyngeal pouch is the embryologic origin of part of the thymus.

Nerves

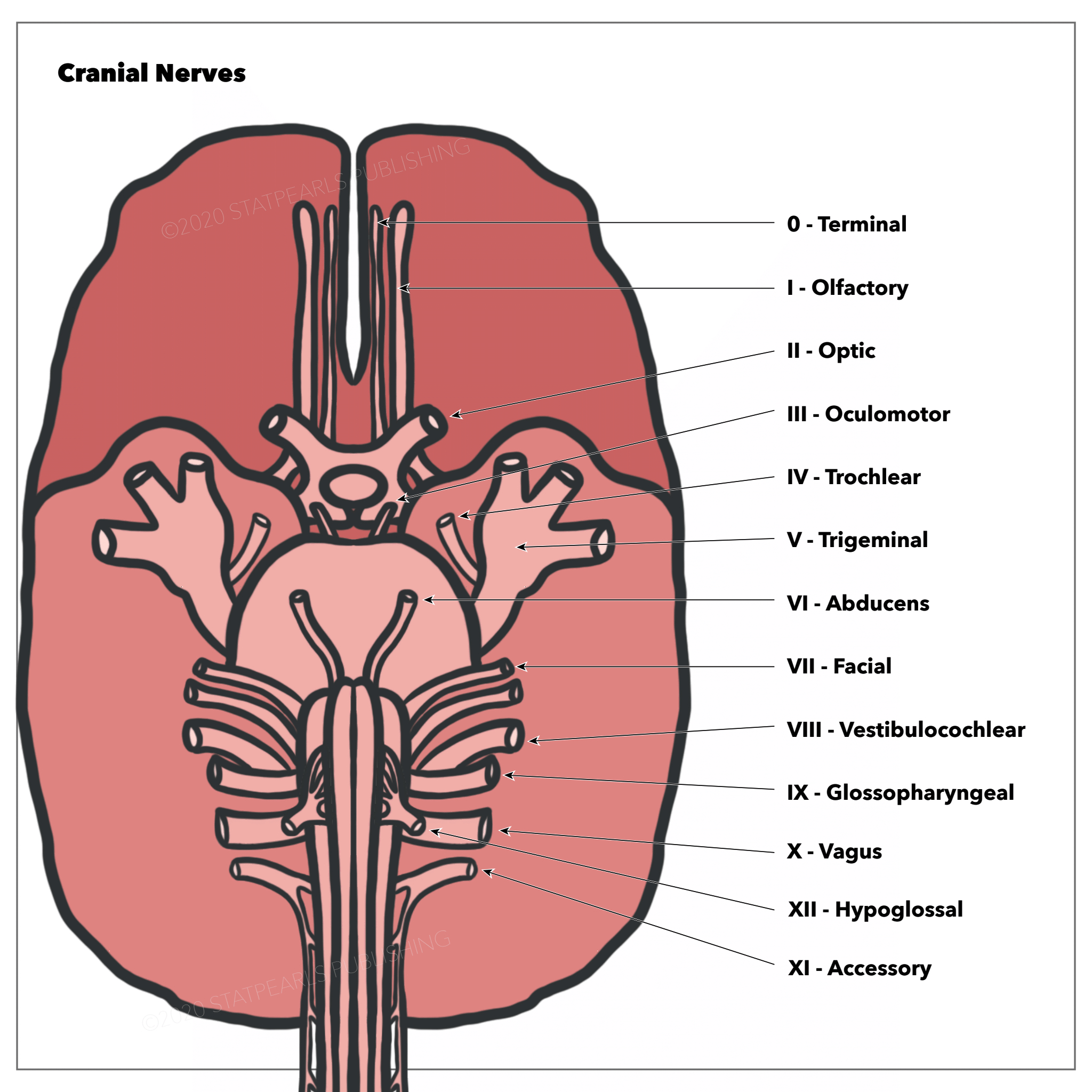

The glossopharyngeal nerve has its origin in the medulla oblongata. It exits the skull via the jugular foramen, where the tympanic nerve branches off to give parasympathetic innervation to the parotid gland. After the jugular foramen are the superior and inferior ganglia, which house the cell bodies of the sensory fibers, and then the nerve descends to the neck, where it provides innervation to the stylopharyngeus and sensation to the carotid sinus and body. It terminates in the pharynx between the superior and middle pharyngeal constrictors, splitting into its other branches – lingual, pharyngeal, and tonsillar (see Image. The Cranial Nerves).[2]

The branches of the glossopharyngeal nerve are:

- Tympanic nerve (AKA nerve of Jacobson) – carries parasympathetic fibers and eventually becomes the lesser petrosal nerve, exiting the skull via the foramen ovale and synapses in the otic ganglion

- Stylopharyngeal nerve – provides motor innervation to the stylopharyngeus muscle

- The nerve to the carotid sinus – communicates with the vagus nerve to carry signals from the baroreceptors in the carotid sinus and chemoreceptors in the carotid body - this helps in regulating blood pressure (carotid sinus) and monitoring blood oxygen and CO2 levels (carotid body)

- Pharyngeal branches – join with the pharyngeal branches of the vagus nerve and sympathetic nerves to form the pharyngeal plexus, which innervates the muscles of the pharynx

- Tonsillar branches – provide sensory innervation to the palatine tonsil

- Lingual branches – supply the vallate papillae, mucous membrane, and follicular glands of the posterior tongue

Muscles

As stated above, the glossopharyngeal nerve provides motor innervation to the stylopharyngeus muscle, which elevates the pharynx and larynx.

Physiologic Variants

Some anatomic variations exist on the course of the glossopharyngeal nerve. In the pharynx, this nerve often curves anteriorly around the stylopharyngeus, but 1 study found that occasionally, it penetrates this muscle.[3] Additionally, 1 study showed that a small subset of the population showed intracranial connections between the glossopharyngeal nerve and the vagus nerve,[4] which merits consideration during posterior fossa surgery to avoid transection of these nerve fibers.

Surgical Considerations

Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia (GPN) is characterized by oropharyngeal pain triggered by mandibular actions, mainly swallowing but also chewing, coughing, and yawning. It is a sporadic condition related to hyperactivity of cranial nerve IX.[5] Glossopharyngeal neuralgia consists of episodic, unilateral sharp pain in the posterior throat, tonsils, base of the tongue, and inferior to the angle of the mandible that can last from seconds to minutes.[5] A subset of patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia also experienced symptoms of excessive vagal stimulation during attacks, with symptoms such as bradycardia, hypotension, syncope, seizures, or cardiac arrest.[6] This condition is classified as classical glossopharyngeal neuralgia, episodic pain, or symptomatic glossopharyngeal neuralgia, where the pain is constant.[5] Idiopathic glossopharyngeal neuralgia is caused by compression of cranial nerve IX by a vessel or dysfunction of the central pons. In contrast, secondary glossopharyngeal neuralgia can result from trauma, neoplasm, infection of the throat, surgery, or malformations.[5]

First-line treatments of GPN are anti-epileptic and anti-depressant medications such as carbamazepine, gabapentin, and pregabalin.[5] Carbamazepine is most often the first medication used in therapy, and if it achieves partial pain relief, a second medication can be added. Also, low-dose selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be useful. If pharmacologic treatments fail, microvascular decompression (MVD) is a safe and effective surgical option.[7] MVD works by surgically relieving the pressure from the vessel compressing the nerve [6] and has been shown to provide almost instant post-surgical relief in most patients.[6] This study suggested that other surgical options, such as percutaneous radiofrequency neurolysis and Gamma Knife radiosurgery, are shown to have early recurrence risks and are generally not widely accepted as effective treatment modalities for glossopharyngeal neuralgia.[6]

Glossopharyngeal Nerve Dysfunction Following Carotid Endarterectomy

During a carotid endarterectomy, injury can occur to different cranial nerves, including the glossopharyngeal nerve (although this is less common than injury to others, such as the hypoglossal and vagus nerves).[8] Transection of this nerve during surgery causes glossopharyngeal nerve paresis, which can cause symptoms such as dysphagia and dysphonia. Damage to the glossopharyngeal nerve without associated vagal nerve damage may present as a mild unilateral decrease in saliva production. One study showed that the incidence of cranial nerve injuries is higher in repeat carotid endarterectomies.[9] A different study showed that risk factors for cranial nerve injuries include atherosclerotic stenosis greater than 2cm, diabetes mellitus, intraoperative trauma or bleeding, high mobilization of the internal carotid artery, and edema of the neck postoperatively.[8]

Clinical Significance

Glossopharyngeal nerve palsy produces the following clinical symptoms/signs:

- Dysphagia

- Impaired gustation over the posterior third of the tongue and palate

- Reduced sensation over the posterior third of the tongue, palate, and pharynx

- Loss of carotid sinus reflex

- Absent gag reflex and

- Parotid gland secretory dysfunction

The clinical conditions likely to affect the IX nerve in particular are:

- Styloid fracture

- Eagle syndrome

- Glossopharyngeal neuralgia[10]

- Iatrogenic injury during the placement of laryngeal mask airway and

- Tonsillar carcinoma

Glossopharyngeal nerve palsy occurs as a part of the following stroke syndromes:

- Vernet syndrome (affecting IX, X, XI)[11]

- Collet-Sicard syndrome (affecting IX, X, XI, XII)

- Villaret syndrome (affecting IX, X, XI, XII, and sympathetic fibers)