[1]

Lam A, Yu A. Overview of flea allergy dermatitis. Compendium (Yardley, PA). 2009 May:31(5):E1-10

[PubMed PMID: 19517416]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

O'Donnell M, Elston DM. What's eating you? human flea (Pulex irritans). Cutis. 2020 Nov:106(5):233-235. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0107. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 33465194]

[5]

Iannino F, Sulli N, Maitino A, Pascucci I, Pampiglione G, Salucci S. Fleas of dog and cat: species, biology and flea-borne diseases. Veterinaria italiana. 2017 Dec 29:53(4):277-288. doi: 10.12834/VetIt.109.303.3. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29307121]

[6]

Halpert E, Borrero E, Ibañez-Pinilla M, Chaparro P, Molina J, Torres M, García E. Prevalence of papular urticaria caused by flea bites and associated factors in children 1-6 years of age in Bogotá, D.C. The World Allergy Organization journal. 2017:10(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s40413-017-0167-y. Epub 2017 Nov 7

[PubMed PMID: 29158868]

[7]

Sanusi ID, Brown EB, Shepard TG, Grafton WD. Tungiasis: report of one case and review of the 14 reported cases in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1989 May:20(5 Pt 2):941-4

[PubMed PMID: 2654224]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[8]

Youssefi MR, Ebrahimpour S, Rezaei M, Ahmadpour E, Rakhshanpour A, Rahimi MT. Dermatitis caused by Ctenocephalides felis (cat flea) in human. Caspian journal of internal medicine. 2014 Fall:5(4):248-50

[PubMed PMID: 25489439]

[9]

Youssefi MR, Rahimi MT. Extreme human annoyance caused by Ctenocephalides felis felis (cat flea). Asian Pacific journal of tropical biomedicine. 2014 Apr:4(4):334-6. doi: 10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C795. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25182561]

[10]

Cestari TF, Pessato S, Ramos-e-Silva M. Tungiasis and myiasis. Clinics in dermatology. 2007 Mar-Apr:25(2):158-64

[PubMed PMID: 17350494]

[11]

Brown LD, Macaluso KR. Rickettsia felis, an Emerging Flea-Borne Rickettsiosis. Current tropical medicine reports. 2016:3():27-39

[PubMed PMID: 27340613]

[12]

Jiang P, Zhang X, Liu RD, Wang ZQ, Cui J. A Human Case of Zoonotic Dog Tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (Eucestoda: Dilepidiidae), in China. The Korean journal of parasitology. 2017 Feb:55(1):61-64. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2017.55.1.61. Epub 2017 Feb 28

[PubMed PMID: 28285500]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[13]

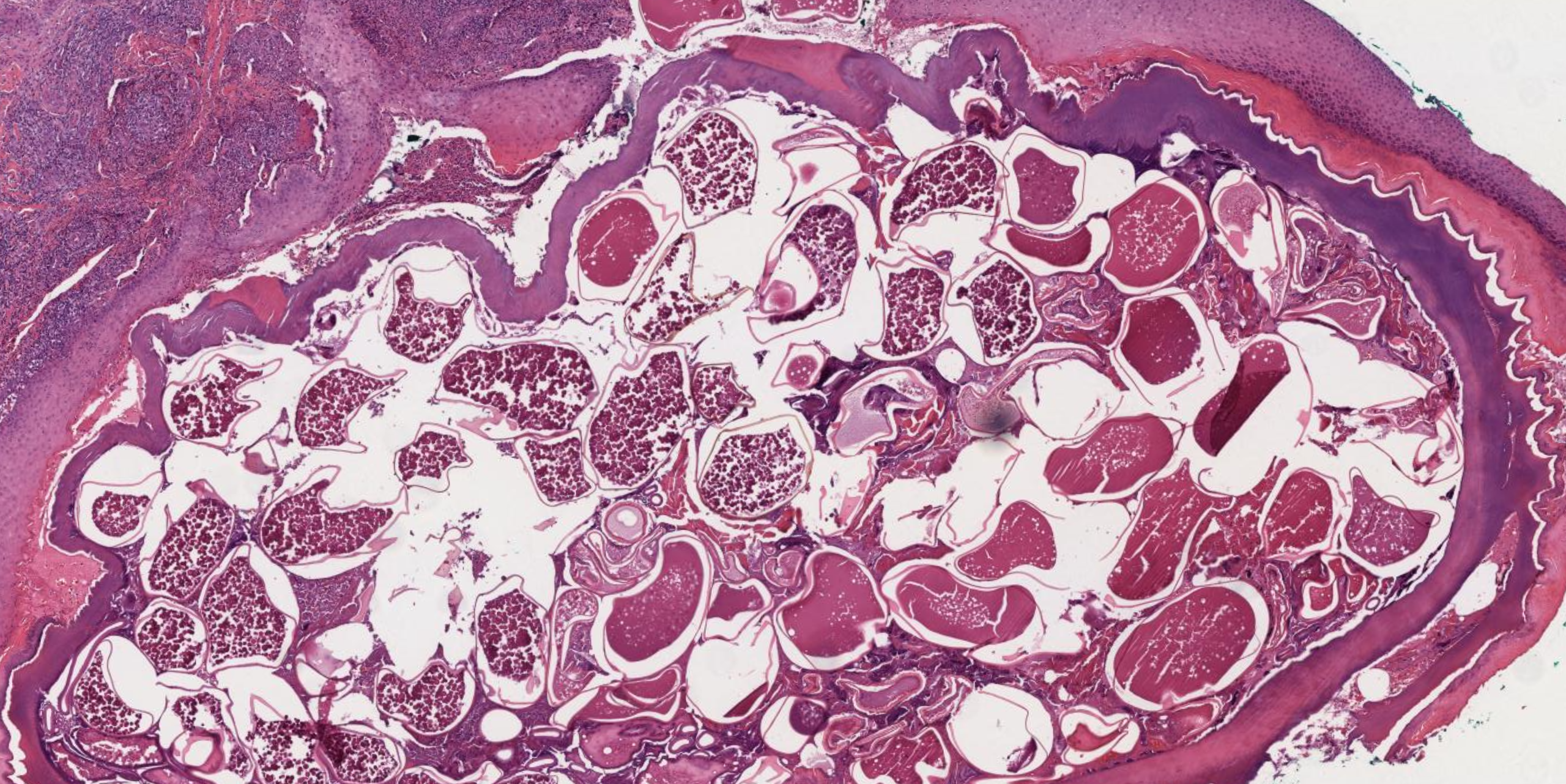

Smith MD, Procop GW. Typical histologic features of Tunga penetrans in skin biopsies. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 2002 Jun:126(6):714-6

[PubMed PMID: 12033962]

[15]

Peres G, Yugar LBT, Haddad Junior V. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner sign: a hallmark of flea and bedbug bites. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2018 Sep-Oct:93(5):759-760. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187384. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30156636]

[16]

Haddad Junior V, Amorim PC, Haddad Junior WT, Cardoso JL. Venomous and poisonous arthropods: identification, clinical manifestations of envenomation, and treatments used in human injuries. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2015 Nov-Dec:48(6):650-7. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0242-2015. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 26676488]

[17]

Singh S, Mann BK. Insect bite reactions. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2013 Mar-Apr:79(2):151-64. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.107629. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 23442453]

[18]

Steen CJ, Carbonaro PA, Schwartz RA. Arthropods in dermatology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2004 Jun:50(6):819-42, quiz 842-4

[PubMed PMID: 15153881]

[19]

Urich SK, Chalcraft L, Schriefer ME, Yockey BM, Petersen JM. Lack of antimicrobial resistance in Yersinia pestis isolates from 17 countries in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2012 Jan:56(1):555-8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05043-11. Epub 2011 Oct 24

[PubMed PMID: 22024826]

[20]

Kwit N, Nelson C, Kugeler K, Petersen J, Plante L, Yaglom H, Kramer V, Schwartz B, House J, Colton L, Feldpausch A, Drenzek C, Baumbach J, DiMenna M, Fisher E, Debess E, Buttke D, Weinburke M, Percy C, Schriefer M, Gage K, Mead P. Human Plague - United States, 2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2015 Aug 28:64(33):918-9

[PubMed PMID: 26313475]

[21]

Perry RD, Fetherston JD. Yersinia pestis--etiologic agent of plague. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1997 Jan:10(1):35-66

[PubMed PMID: 8993858]

[23]

Civen R, Ngo V. Murine typhus: an unrecognized suburban vectorborne disease. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2008 Mar 15:46(6):913-8. doi: 10.1086/527443. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 18260783]

[24]

Tsioutis C, Zafeiri M, Avramopoulos A, Prousali E, Miligkos M, Karageorgos SA. Clinical and laboratory characteristics, epidemiology, and outcomes of murine typhus: A systematic review. Acta tropica. 2017 Feb:166():16-24. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2016.10.018. Epub 2016 Oct 29

[PubMed PMID: 27983969]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[25]

Dumler JS, Taylor JP, Walker DH. Clinical and laboratory features of murine typhus in south Texas, 1980 through 1987. JAMA. 1991 Sep 11:266(10):1365-70

[PubMed PMID: 1880866]

[26]

Vander T, Medvedovsky M, Valdman S, Herishanu Y. Facial paralysis and meningitis caused by Rickettsia typhi infection. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases. 2003:35(11-12):886-7

[PubMed PMID: 14723370]

[27]

Newton PN, Keolouangkhot V, Lee SJ, Choumlivong K, Sisouphone S, Choumlivong K, Vongsouvath M, Mayxay M, Chansamouth V, Davong V, Phommasone K, Sirisouk J, Blacksell SD, Nawtaisong P, Moore CE, Castonguay-Vanier J, Dittrich S, Rattanavong S, Chang K, Darasavath C, Rattanavong O, Paris DH, Phetsouvanh R. A Prospective, Open-label, Randomized Trial of Doxycycline Versus Azithromycin for the Treatment of Uncomplicated Murine Typhus. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2019 Feb 15:68(5):738-747. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy563. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30020447]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[28]

Shaked Y, Samra Y, Maier MK, Rubinstein E. Relapse of rickettsial Mediterranean spotted fever and murine typhus after treatment with chloramphenicol. The Journal of infection. 1989 Jan:18(1):35-7

[PubMed PMID: 2915129]

[29]

Stenger F, Seidel P, Schricker T, Volc S, Fischer J. Could Cat Flea Bites Contribute to a-Gal Serum IgE Levels in Humans? Journal of investigational allergology & clinical immunology. 2022 Dec 15:32(6):494-495. doi: 10.18176/jiaci.0784. Epub 2022 Jan 28

[PubMed PMID: 35088764]

[30]

Prospero Ponce CM, Malik AI, Vickers A, Chevez-Barrios P, Lee AG. Orbital Inflammatory Syndrome Secondary to Flea Bite. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Jul/Aug:34(4):e115-e118. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000001115. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29659432]

[31]

Rust MK. Advances in the control of Ctenocephalides felis (cat flea) on cats and dogs. Trends in parasitology. 2005 May:21(5):232-6

[PubMed PMID: 15837612]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[32]

Rust MK. The Biology and Ecology of Cat Fleas and Advancements in Their Pest Management: A Review. Insects. 2017 Oct 27:8(4):. doi: 10.3390/insects8040118. Epub 2017 Oct 27

[PubMed PMID: 29077073]