Continuing Education Activity

A fasciotomy is a procedure used to decompress acute compartment syndrome. Most commonly, acute compartment syndrome occurs in the leg and the forearm in the setting of acute trauma. This activity highlights the exact steps needed to perform 2 common fasciotomies. A high index of suspicion is necessary for the early detection of compartment syndrome, and a low threshold for intervention is needed by a trained healthcare professional.

Objectives:

- Identify the indications for fasciotomy.

- Apply the technique of fasciotomy.

- Assess for the potential complications of fasciotomy.

- Create strategies with the interprofessional team for improving care coordination when performing fasciotomies to improve outcomes.

Introduction

A fasciotomy is an emergency procedure used to treat acute compartment syndrome. Compartment syndrome is when the pressure builds up in a non-compliant osseofascial compartment and causes ischemia leading to muscle and nerve necrosis. It occurs most commonly in the volar compartment of the forearm, deep posterior, or anterior leg compartment. It can, however, happen in any closed space where the muscle is surrounded by substantial fascia, eg, the hand, foot, thigh, or buttock.

Compartment syndrome categorizes as acute or chronic. Acute compartment syndrome often follows high-energy trauma, fractures, circumferential burns, crush injuries, or a tight plaster cast. Chronic compartment syndrome develops with muscular overuse and commonly occurs in the leg of runners or military personnel or the forearm of weightlifters and rowers. Occasionally acute exertional compartment syndrome can be seen after strenuous exertion.

Anatomy and Physiology

The lower leg is the most frequent site of compartment syndrome and associated fasciotomy. The lower leg divides into 4 anatomical compartments: anterior, lateral, superficial posterior, and deep posterior.

Anatomical Structures of the Lower Leg

- Anterior compartment of the lower leg

- Tibialis anterior

- Extensor halluces longus

- Extensor digitorum longus

- Peroneus tertius

- Deep fibular nerve

- Anterior tibial artery

- Lateral compartment of the lower leg

- Peroneus longus

- Peroneus tertius

- Superficial fibular nerve

- Fibular artery

- Superficial posterior compartment of the lower leg

- Gastrocnemius

- Soleus

- Plantaris

- Sural nerve

- Deep posterior compartment of the lower leg

- Tibialis posterior

- Flexor hallucis longus

- Flexor digitorum longus

- Popliteus

- Tibial nerve

- Posterior tibial artery

The forearm is the most common site of compartment syndrome in the upper limb. The forearm subdivides into 4 anatomical compartments: superficial volar, deep volar, dorsal compartment, and the mobile wad of Henry. The volar compartments are most commonly affected.

Anatomical Structures of the Upper Limb

- Superficial volar compartment of the upper limb

- Flexor carpi ulnaris

- Flexor carpi radialis

- Pronator teres

- Palmaris longus

- Flexor digitorum superficialis of the upper limb (often described as being in an intermediate volar compartment)

- Ulnar nerve

- Ulnar artery

- Deep volar compartment of the upper limb

- Flexor digitorum profundus

- Flexor pollicis longus

- Pronator quadratus

- Median nerve

- Anterior interosseous artery

- Anterior interosseous nerve

- Dorsal compartment of the upper limb

- Extensor digitorum

- Extensor digiti minimi

- Extensor carpi ulnaris

- Supinator

- Extensor indicis

- Extensor pollicis longus

- Extensor pollicis brevis

- Abductor pollicis longus

- Posterior interosseous nerve

- Posterior interosseus artery

- Mobile wad of Henry of the upper limb

- Brachioradialis

- Extensor carpi radialis longus

- Extensor carpi radialis brevis

- Radial nerve

- Radial artery

The median and ulnar nerves lie in the volar forearm between the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus. The radial nerve lies deep to the mobile wad.

Indications

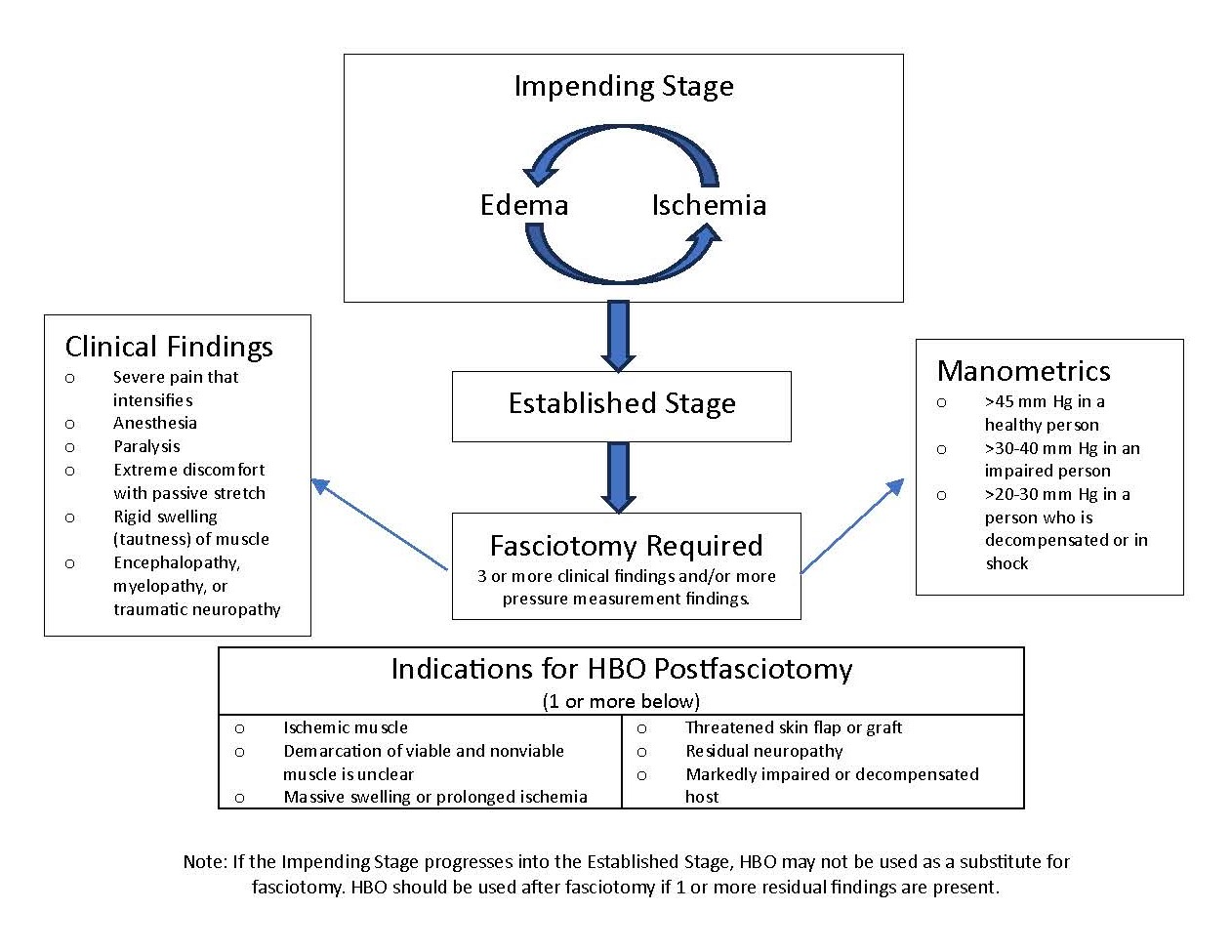

The classical features of compartment syndrome are ischemia, pain out of proportion to the injury, paraesthesia, pallor, paralysis, and pain on passive movement, especially stretch of the concerned compartment. Two-point discrimination can be useful for determining nerve ischemia. Depending on the conscious level, sensory state, and communication ability, these signs and symptoms can be challenging to assess. In these circumstances, monitoring of compartment pressures can be useful.[1][2][3]. (see Image Fasciotomy and Indications for HBO)

Measuring compartment pressures is possible via multiple methods, none of which have robust supporting evidence. No universal agreement exists on indications for emergency fasciotomy. Some institutes operate if the difference between the compartment pressure and diastolic pressure is less than 20 mmHg. While some surgeons operate if a compartment pressure is greater than 30 mmHg with the correlation of clinical signs.[4][5]

Contraindications

No absolute contraindication to performing a fasciotomy exists. This section will explore the relative contraindications. Every decision to perform an emergency fasciotomy should be made by a senior team member and on a case-by-case basis considering the patient's medical condition and the injury sustained.

The primary relative contraindication to performing a fasciotomy is delayed presentation. If the clinician suspects compartment syndrome has been present for more than 12 hours, there is a potential risk of reperfusion injury.

One study demonstrated that fasciotomies performed within 6 hours resulted in almost complete limb function recovery; fasciotomies performed between 6 and 12 hours resulted in a normal functional recovery rate of 68%. However, fasciotomies performed after 12 hours resulted in only 8% of patients regaining normal limb function.[6] Conversely, another more recent study revealed no difference in limb salvage rate when comparing early (<12 h) to late (>12 h) fasciotomy. The infection rate was significantly higher in patients with delayed fasciotomies.[7] In a 2008 study, 336 combat patients received 643 fasciotomies (upper and lower limb included). Patients who underwent a delayed fasciotomy had twice the amputation rate and 3 times the mortality rate.[8]

Considerations of irreversible nerve and muscle damage and high risk of infection change the risk-benefit analysis in missed compartment syndrome and negate the necessity for emergency surgery.[9][7]

Equipment

The equipment used to perform a fasciotomy is listed below.

- Antiseptic solution for skin preparation

- Skin scalpel

- Inside scalpel

- Forceps

- Simple hand-held retractor (Langenbeck)

- Diathermy device

- Dressing

Personnel

The procedure can be carried out by any medical professional with the appropriate training; often this is a surgical resident or attending. The one performing the fasciotomy needs direct assistance from a scrub nurse and an anesthetist at a minimum.

Preparation

Before the procedure begins, the surgical team should complete the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. For a fasciotomy of the leg, the patient is positioned supine. The leg should be prepped and draped to above the knee. For a forearm fasciotomy, the patient should be positioned supine with the arm abducted to 90 on a table extension. The patient should then be prepped and draped to above the elbow.

Technique or Treatment

Single-Incision Fasciotomy of the Leg (Davey, Rorabeck, and Fowler Technique)

- Make a skin incision beginning at the lateral malleolus and extending proximally along the fibula for the full length of the compartment.

- Develop the subcutaneous plane anteriorly to expose the fascial layer. Be aware of damage to the superficial peroneal nerve at this stage.

- Make a longitudinal incision in the anterior and lateral fascial compartments.

- Develop the subcutaneous plane posteriorly and perform a longitudinal incision into the superficial posterior compartment.

- Identify the soleus in the superficial posterior compartment and begin to develop the plane between the distal third of the soleus and the lateral compartment.

- Remove the soleus and the deeper flexor hallucis longus from the posterior fibula. Be aware the peroneal neurovascular bundle will be immediately medial to the fibula.

- Retract the peroneal vessels posteriorly to expose the fascial attachment of the tibialis posterior to the fibula and make a longitudinal incision.

- Apply appropriate wound dressing.

Double Incision Fasciotomy of the Leg (Mubarak and Harges Technique)

- Anterolateral incision

- Make a 20 cm anterior skin incision centered between the crest of the tibia and the fibula.

- Identify the anterior intramuscular septum and make a longitudinal incision on either side into the anterior and lateral compartments.

- Posteromedial incision

- Make a second skin incision starting 2 cm proximal and 2 cm superior to the medial malleolus of the tibia, extending proximally in line with the tibia longitudinally.

- Carefully use blunt dissection to identify the fascial layer, the long saphenous vein, and the saphenous nerve; retract these anteriorly.

- Make an incision along the length of the posterior fascial compartment.

- Make another fascial incision over the flexor digitorum longus muscle immediately posterior and medial to the tibia to release the posterior compartment.

Forarm Fasciotomy

- Volar Incision

- Make a large skin incision starting just radial to the flexor carpi ulnaris and extending proximally to the medial epicondyle.

- Extend the incision distally to the wrist crease, cross the wrist crease diagonally towards the hypothenar eminence and into the palm to facilitate a carpal tunnel release.

- Make a longitudinal incision into the superficial fascial compartment.

- Retract the flexor carpi ulnaris and the ulnar neurovascular bundle medially.

- Retract the flexor digitorum superficialis medially. This exposes the deep fascial compartment.

- Make a fascial incision onto the flexor digitorum profundus.

- Extend both fascial incisions to the transverse carpal ligament.

- Dorsal Incision

- Make a 10-cm incision in the skin between the extensor digitorum communis and extensor carpi radialis brevis starting 2 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle. This incision allows the release of the fascia over the mobile wad immediately.

- Develop the subcutaneous plane posteriorly to expose the extensor retinaculum and release the fascia to decompress the posterior compartment.

Follow-up

Fasciotomy wound management begins with an inspection at 48 hours. If the compartments are soft, this closure is achieved by primary wound closure, secondary wound healing, or split-thickness skin grafting. Split-thickness grafting is needed in approximately 50% of wounds. Delayed primary closure is also feasible using a vessel loop shoelace stitch. The use of a negative pressure wound management device is another option.

Complications

Due to muscle necrosis, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure are common; treatment is with intravenous fluids and dialysis.[9]

Incomplete fasciotomies can create a need for a revision fasciotomy either to extend the fascial opening or open a missed compartment. Compartments are most commonly overlooked when the anatomy is highly distorted, such as in cases of high-energy trauma or patients with previous surgery and scarring. In these patients, the associated mortality increased by 4 times.[8]

Also, patients who underwent a delayed fasciotomy have twice the amputation rate and 3 times the mortality. In some cases, even with timely fasciotomies, the affected limb may not regain normal functionality and may result in an amputation.

Wound Complications are as follows:[10][11]

- Need for skin grafting

- Scaring

- Tendon tethering

- Muscle herniation

- Recurrent ulceration

- Swollen limbs

- Discolored wounds

- Pruritus

- Dry, scaly skin

- Altered sensation

Clinical Significance

Early recognition and subsequent treatment of compartment syndrome with fasciotomies cause a significant decrease in poor functional outcomes, the need for amputation, and the risk of death. Additionally, the medico-legal burden of delayed fasciotomies is high. The time from symptom onset to fasciotomy is directly linked to an increasing payout in medical negligence claims. Fasciotomy performed early is associated with a successful defense of medico-legal action.[12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Early recognition of compartment syndrome is best detected by those professionals who have regular contact with the patients in the hospital. The hospital staff, typically attending physicians and nursing staff, has the most contact time with patients and is in the best position to detect increasing symptom severity. These staff members need the most training in recognizing compartment syndrome and need to exercise a high index of suspicion. The ability to escalate the situation in a timely fashion to a senior physician who can initiate early aggressive treatment with fasciotomy is crucial. Therefore, department management is responsible for ensuring all healthcare team members have adequate training in recognizing the symptoms, are familiar with pressure measuring equipment, and can escalate the situation appropriately and promptly. Implementing an interprofessional approach provides the best method for early detection to provide the best patient outcomes.