Introduction

The fallopian tubes are bilateral conduits between the ovaries and the uterus in the female pelvis. They function as channels for oocyte transport and fertilization. Given this role, the fallopian tubes are a common etiology of infertility as well as the target of purposeful surgical sterilization. They can also be sites of ascending infection or neoplasms.

Structure and Function

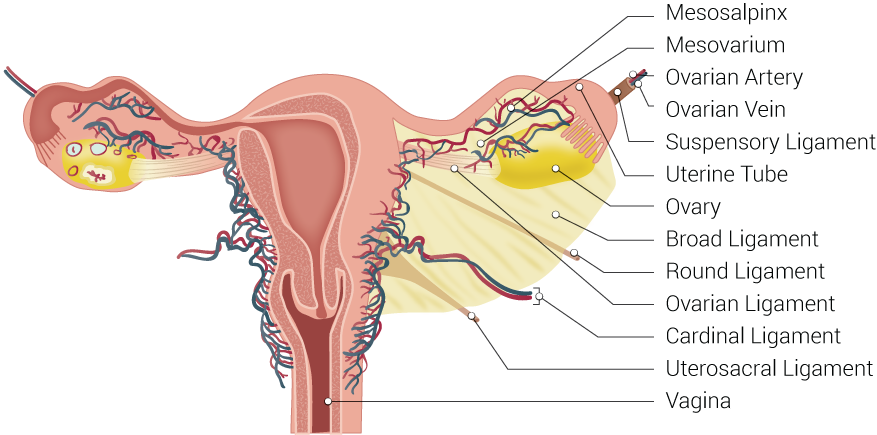

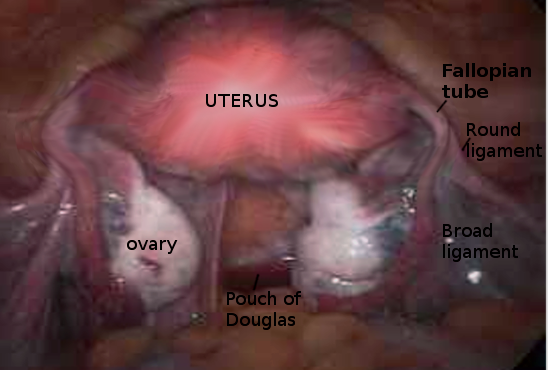

Fallopian tubes, otherwise called oviducts or uterine tubes, are hollow seromuscular organs that originate at the uterine horns, extend laterally within the superior edge of the mesosalpinx of the broad ligament, and terminate near the ipsilateral ovary. They are 11 to 12 cm in length and have a lumen diameter of less than 1 mm.[1] The fallopian tube comprises four anatomical regions: uterine, isthmus, ampulla, and infundibulum. Most medially, the uterine part includes the uterine ostium and a short segment nearest to the uterine horn. The isthmus is adjacent to the uterine part. Lateral to the isthmus is the ampulla, the most common site of fertilization. Most distal from the uterus, the infundibulum ends at an abdominal ostium opening up into the peritoneal cavity and fimbriae, which catch the released oocyte during each menstrual cycle. One fimbria, named the fimbria ovarica, serves to connect the infundibulum to the ovary nearby. In addition to providing a space for fertilization to occur, the fallopian tubes function as a passageway for the ovum or gamete from the ovary to the uterus.[2]

Embryology

The paramesonephric ducts, otherwise known as the Mullerian ducts, form in female embryos at around week five or six due to the absence of anti-mullerian hormone (AMH). With estrogen stimulation, the cranial ends of these ducts eventually form the fallopian tubes. Caudally, the paramesonephric ducts fuse in the midline and ultimately form the uterus and superior vagina. Most cranially, a remnant of the paramesonephric duct may persist as a vestigial structure called the vesicular appendage or the hydatid cyst of Morgagni.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The arterial supply to the fallopian tube arises from anastomoses between the ovarian and tubal branches of the ovarian artery and ascending branches of the uterine artery. On each side, the ovarian arteries branch off the abdominal aorta inferior to the origin of the renal arteries. The uterine arteries stem from the internal iliac arteries, and the ascending branches travel superiorly towards the uterine horns while its descending branches travel inferiorly towards the superior vagina. The ovarian arteries supply the lateral fallopian tube, while the ascending branches of the uterine artery supply the medial fallopian tube; however, anastomoses between the two generally ensures that compromise of either will not cause ischemia of any portion of the tube.

The venous drainage goes to the tubal branches of the uterine and ovarian veins, in a similar configuration as the arterial supply. The inferior vena cava (IVC) receives the drainage from the right ovarian vein, while the left renal vein receives the drainage from the left ovarian vein. The uterine veins drain into the internal iliac veins, which drain into the IVC.

Lymph drainage of the fallopian tubes is similar to that of the ovaries. Lymph flows from the fallopian tubes to both the para-aortic (lumbar) lymph nodes and the pelvic lymph nodes.[2][4]

Nerves

Afferent pain fibers for the fallopian tubes travel along the same pathway as sympathetic efferent innervation, which originates from T11, T12, and L1. By contrast, minor parasympathetic innervation is shared between vagal fibers of the ovarian plexus for the lateral part of the fallopian tube and medially from the pelvic splanchnic nerve from S1, S2, and S3. The most medial isthmus receives the densest innervation, and both innervation and musculature become sparser from proximal to the distal fallopian tube.[5]

Muscles

The muscular layer of the fallopian tubes gets sandwiched between the inner mucosa, which contains longitudinal cilia extending into the lumen, and the outermost serosa. This layer is also known as the muscularis mucosa and comprises an inner circular layer and outer longitudinal layer.

The contractions of this muscular layer work in conjunction with cilia movements and tubal secretory fluids to achieve ovum or gamete transport along the length of the fallopian tube. Short, frequent contractions help mix tubal fluid, while continuous tonic contractions not only contribute to anterograde transport of ovum or gamete but also allow the admission of an embryo across the utero-tubal junction at the most hormonally optimal point in time during the menstrual cycle.[5]

Physiologic Variants

Benign para tubal cysts may be found incidentally on ultrasound or during surgeries. These cysts appear most often in middle age and are usually asymptomatic. The previously mentioned hydatid of Morgagni, an embryologic remnant, may also be present at the distal-most part of the fallopian tube.

There have been rare reported cases of fallopian tube diverticula, agenesis, and duplication. Diverticula or duplications increase the risk of tubal pathologies such as hydrosalpinx or torsion, as well as ectopic pregnancies. Tubal abnormalities leading to occlusion or tubal agenesis may contribute to infertility. Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure in utero, in particular, has been linked to abnormal development of the fallopian tube.[6][7]

Surgical Considerations

Commonly performed surgical procedures involving the fallopian tubes include[8][9]:

- Salpingo-oophorectomy: removal of the ovary and fallopian tube

- Salpingectomy: removal of the fallopian tube

- Salpingostomy: surgical incision into the fallopian tube to create an opening

- Tubal ligation: an umbrella term for female surgical sterilization by occlusion, removal, or ligation of fallopian tubes

Clinical Significance

Fallopian tubes are involved in several gynecologic diseases that necessitate the procedures mentioned earlier. The ampulla is the most common site of ectopic pregnancies, which are either treated medically or removed surgically with a salpingostomy (creating an opening in the tube) or salpingectomy (tube excision and removal). Removal of the fallopian tubes may be necessary for malignancies involving the ovary, fallopian tube, or uterus, as well as benign conditions, including hydrosalpinx and tubo-ovarian abscess.

Fallopian tubes have a unique significance in the context of ovarian cancer. High grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), the most common type of ovarian cancer, is often diagnosed at an advanced stage, leading to poor prognosis. Recent evidence has shown that most cases of HGSOC originate in the fallopian tubes years before the presentation of ovarian cancer.[10]

A tubal ligation is an option for patients desiring permanent sterilization. This procedure is regarded as very safe and highly effective. Patients should, however, understand that it is permanent, and clinicians should be aware of the risk factors for post-procedure regret, including age less than 30, lower parity, sterilization performed in the immediate postpartum period, and low socioeconomic status.[11][8][9]

Other Issues

Abnormalities of the fallopian tubes have been implicated in up to one-third of infertility cases. Causes that may negatively impact fallopian tube structure or function include congenital absence or malformation, infections such as Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhea, genital tuberculosis, and endometriosis adhesions, causing tubal distortion. As such, a history of recurrent pelvic inflammatory disease related to these infections or a history of intra-abdominal surgery leading to adhesions correlates with a higher risk of tubal factor infertility. An increased number of past infections also correlates with increased severity of damage to the fallopian tubes.[12]

Tubal occlusion investigation can be by hysterosalpingography or hysteroscopy. Interventions for occlusion specific to the fallopian tube include selective salpingography, recanalization, re-anastomosis, and neosalpingostomy.[1]