[1]

Patel BC. In Praise of Precision: Esoglobus and Exoglobus. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Jan/Feb:33(1):72-73. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000817. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27811634]

[2]

Erkoç MF, Öztoprak B, Gümüş C, Okur A. Exploration of orbital and orbital soft-tissue volume changes with gender and body parameters using magnetic resonance imaging. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2015 May:9(5):1991-1997

[PubMed PMID: 26136927]

[3]

Ahmad Nasir S, Ramli R, Abd Jabar N. Predictors of enophthalmos among adult patients with pure orbital blowout fractures. PloS one. 2018:13(10):e0204946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0204946. Epub 2018 Oct 5

[PubMed PMID: 30289909]

[5]

Arikan OK, Onaran Z, Muluk NB, Yilmazbaş P, Yazici I. Enophthalmos due to atelectasis of the maxillary sinus: silent sinus syndrome. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2009 Nov:20(6):2156-9. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181bf0116. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 19884840]

[6]

Rapidis AD, Liarikos S, Ntountas J, Patel BC. The silent sinus syndrome: report of 2 cases. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2004 Aug:62(8):1028-33

[PubMed PMID: 15278871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[7]

Jacobs JM,Chou EL,Tagg NT, Rapid remodeling of the maxillary sinus in silent sinus syndrome. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2019 Apr;

[PubMed PMID: 29742007]

[9]

Ascher B, Coleman S, Alster T, Bauer U, Burgess C, Butterwick K, Donofrio L, Engelhard P, Goldman MP, Katz P, Vleggaar D. Full scope of effect of facial lipoatrophy: a framework of disease understanding. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2006 Aug:32(8):1058-69

[PubMed PMID: 16918569]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[10]

Rose GE. The giant fornix syndrome: an unrecognized cause of chronic, relapsing, grossly purulent conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2004 Aug:111(8):1539-45

[PubMed PMID: 15288985]

[11]

Liang L, Sheha H, Fu Y, Liu J, Tseng SC. Ocular surface morbidity in eyes with senile sunken upper eyelids. Ophthalmology. 2011 Dec:118(12):2487-92. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.035. Epub 2011 Aug 27

[PubMed PMID: 21872934]

[12]

Bucher F,Fricke J,Neugebauer A,Cursiefen C,Heindl LM, Ophthalmological manifestations of Parry-Romberg syndrome. Survey of ophthalmology. 2016 Nov - Dec;

[PubMed PMID: 27045226]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[13]

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J, Kalra S, Kaltsas G, Kapoor N, Koch C, Kopp P, Korbonits M, Kovacs CS, Kuohung W, Laferrère B, Levy M, McGee EA, McLachlan R, New M, Purnell J, Sahay R, Shah AS, Singer F, Sperling MA, Stratakis CA, Trence DL, Wilson DP, Akinci B, Gular MC, Oral EA. Lipodystrophy Syndromes: Presentation and Treatment. Endotext. 2000:():

[PubMed PMID: 29989768]

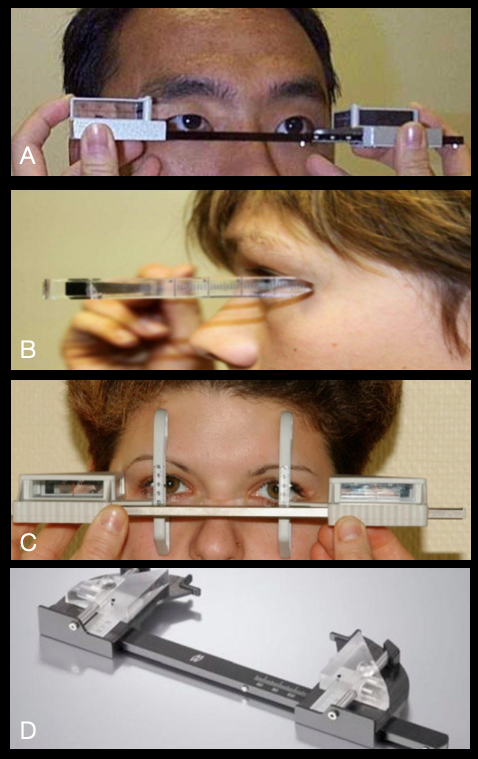

[14]

Bielsa Marsol I. Update on the classification and treatment of localized scleroderma. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas. 2013 Oct:104(8):654-66. doi: 10.1016/j.adengl.2012.10.012. Epub 2013 Aug 13

[PubMed PMID: 23948159]

[15]

George R, George A, Kumar TS. Update on Management of Morphea (Localized Scleroderma) in Children. Indian dermatology online journal. 2020 Mar-Apr:11(2):135-145. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_284_19. Epub 2020 Mar 9

[PubMed PMID: 32477969]

[16]

Kapoor AG, Kumar SV, Bhagyalakshmi N. Localized scleroderma causing enophthalmos: A rare entity. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Nov:66(11):1611-1612. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_303_18. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30355873]

[17]

Hock LE, Kontzialis M, Szewka AJ. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre presenting with positional diplopia and enophthalmos. Neurology. 2016 Oct 18:87(16):1741-1742

[PubMed PMID: 27754909]

[18]

Khatri S, Torok KS, Mirizio E, Liu C, Astakhova K. Autoantibodies in Morphea: An Update. Frontiers in immunology. 2019:10():1487. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01487. Epub 2019 Jul 9

[PubMed PMID: 31354701]

[19]

Kelsey CE, Torok KS. The Localized Scleroderma Cutaneous Assessment Tool: responsiveness to change in a pediatric clinical population. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013 Aug:69(2):214-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.02.007. Epub 2013 Apr 4

[PubMed PMID: 23562760]

[20]

Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2015 Jan-Feb:90(1):62-73. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152890. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 25672301]

[21]

Koornneef L. Eyelid and orbital fascial attachments and their clinical significance. Eye (London, England). 1988:2 ( Pt 2)():130-4

[PubMed PMID: 3197870]

[22]

Novitskaya E, Rene C. Enophthalmos as a sign of metastatic breast carcinoma. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2013 Sep 17:185(13):1159. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120726. Epub 2013 Mar 4

[PubMed PMID: 23460637]

[23]

Shields JA, Shields CL, Brotman HK, Carvalho C, Perez N, Eagle RC Jr. Cancer metastatic to the orbit: the 2000 Robert M. Curts Lecture. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2001 Sep:17(5):346-54

[PubMed PMID: 11642491]

[24]

Ahmad SM,Esmaeli B, Metastatic tumors of the orbit and ocular adnexa. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2007 Sep;

[PubMed PMID: 17700235]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[25]

Orr CK, Cochran E, Shinder R. Metastatic Scirrhous Breast Carcinoma to Orbit Causing Enophthalmos. Ophthalmology. 2016 Jul:123(7):1529. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.04.012. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 27342331]

[26]

Homer N, Jakobiec FA, Stagner A, Cunnane ME, Freitag SK, Fay A, Yoon MK. Periocular breast carcinoma metastases: correlation of clinical, radiologic and histopathologic features. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology. 2017 Aug:45(6):606-612. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12926. Epub 2017 Mar 3

[PubMed PMID: 28181367]

[27]

Allen RC. Orbital Metastases: When to Suspect? When to biopsy? Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Apr-Jun:25(2):60-64. doi: 10.4103/meajo.MEAJO_93_18. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30122850]

[28]

Hamedani M,Pournaras JA,Goldblum D, Diagnosis and management of enophthalmos. Survey of ophthalmology. 2007 Sep-Oct;

[PubMed PMID: 17719369]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[30]

Bite U, Jackson IT, Forbes GS, Gehring DG. Orbital volume measurements in enophthalmos using three-dimensional CT imaging. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1985 Apr:75(4):502-8

[PubMed PMID: 3838589]

[31]

Delmas J, Loustau JM, Martin S, Bourmault L, Adenis JP, Robert PY. Comparative study of 3 exophthalmometers and computed tomographic biometry. European journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Mar:28(2):144-149. doi: 10.5301/ejo.5001049. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29108394]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[32]

Jeon HB,Kang DH,Oh SA,Gu JH, Comparative Study of Naugle and Hertel Exophthalmometry in Orbitozygomatic Fracture. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2016 Jan;

[PubMed PMID: 26674913]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[33]

Zhang Z, Zhang Y, He Y, An J, Zwahlen RA. Correlation between volume of herniated orbital contents and the amount of enophthalmos in orbital floor and wall fractures. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2012 Jan:70(1):68-73. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2011.02.036. Epub 2011 Jun 12

[PubMed PMID: 21664740]

[34]

Afanasyeva DS, Gushchina MB, Gerasimov MY, Borzenok SA. Computed exophthalmometry is an accurate and reproducible method for the measuring of eyeballs' protrusion. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 2018 Mar:46(3):461-465. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2017.12.024. Epub 2017 Dec 26

[PubMed PMID: 29325888]

[35]

Boyette JR, Pemberton JD, Bonilla-Velez J. Management of orbital fractures: challenges and solutions. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2015:9():2127-37. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S80463. Epub 2015 Nov 17

[PubMed PMID: 26604678]

[36]

Nightingale CL,Shakib K, Analysis of contemporary tools for the measurement of enophthalmos: a PRISMA-driven systematic review. The British journal of oral

[PubMed PMID: 31431316]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[37]

Young SM, Kim YD, Kim SW, Jo HB, Lang SS, Cho K, Woo KI. Conservatively Treated Orbital Blowout Fractures: Spontaneous Radiologic Improvement. Ophthalmology. 2018 Jun:125(6):938-944. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.12.015. Epub 2018 Feb 3

[PubMed PMID: 29398084]

[38]

Ramasamy A, Madhan B, Krishnan B. Comments on "A Straightforward Method of Predicting Enophthalmos in Blowout Fractures Using Enophthalmos Estimate Line". Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2017 Jun:75(6):1094. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2017.01.045. Epub 2017 Mar 6

[PubMed PMID: 28279685]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[39]

McRae M, Augustine HFM, Budning A, Antonyshyn O. Functional Outcomes of Late Posttraumatic Enophthalmos Correction. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Aug:142(2):169e-178e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004600. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30045183]

[40]

Thomas RD,Graham SM,Carter KD,Nerad JA, Management of the orbital floor in silent sinus syndrome. American journal of rhinology. 2003 Mar-Apr;

[PubMed PMID: 12751704]

[41]

Tripathy K, Chawla R, Temkar S, Sagar P, Kashyap S, Pushker N, Sharma YR. Phthisis Bulbi-a Clinicopathological Perspective. Seminars in ophthalmology. 2018:33(6):788-803. doi: 10.1080/08820538.2018.1477966. Epub 2018 Jun 14

[PubMed PMID: 29902388]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[42]

Hazani R, Yaremchuk MJ. Correction of posttraumatic enophthalmos. Archives of plastic surgery. 2012 Jan:39(1):11-7. doi: 10.5999/aps.2012.39.1.11. Epub 2012 Jan 15

[PubMed PMID: 22783485]

[43]

Kim YH, Ha JH, Kim TG, Lee JH. Posttraumatic enophthalmos: injuries and outcomes. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2012 Jul:23(4):1005-9. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e31824e6a1a. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 22777457]

[44]

Aryasit O, Preechawai P, Hirunpat C, Horatanaruang O, Singha P. Factors related to survival outcomes following orbital exenteration: a retrospective, comparative, case series. BMC ophthalmology. 2018 Jul 28:18(1):186. doi: 10.1186/s12886-018-0850-y. Epub 2018 Jul 28

[PubMed PMID: 30055580]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[45]

Ugradar S, Lo C, Manoukian N, Putthirangsiwong B, Rootman D. The Degree of Posttraumatic Enophthalmos Detectable by Lay Observers. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2019 Jun:35(3):306-310. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1688945. Epub 2019 May 17

[PubMed PMID: 31100769]

[46]

Kolk A, Pautke C, Schott V, Ventrella E, Wiener E, Ploder O, Horch HH, Neff A. Secondary post-traumatic enophthalmos: high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging compared with multislice computed tomography in postoperative orbital volume measurement. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2007 Oct:65(10):1926-34

[PubMed PMID: 17884517]